Security in a disrupted world

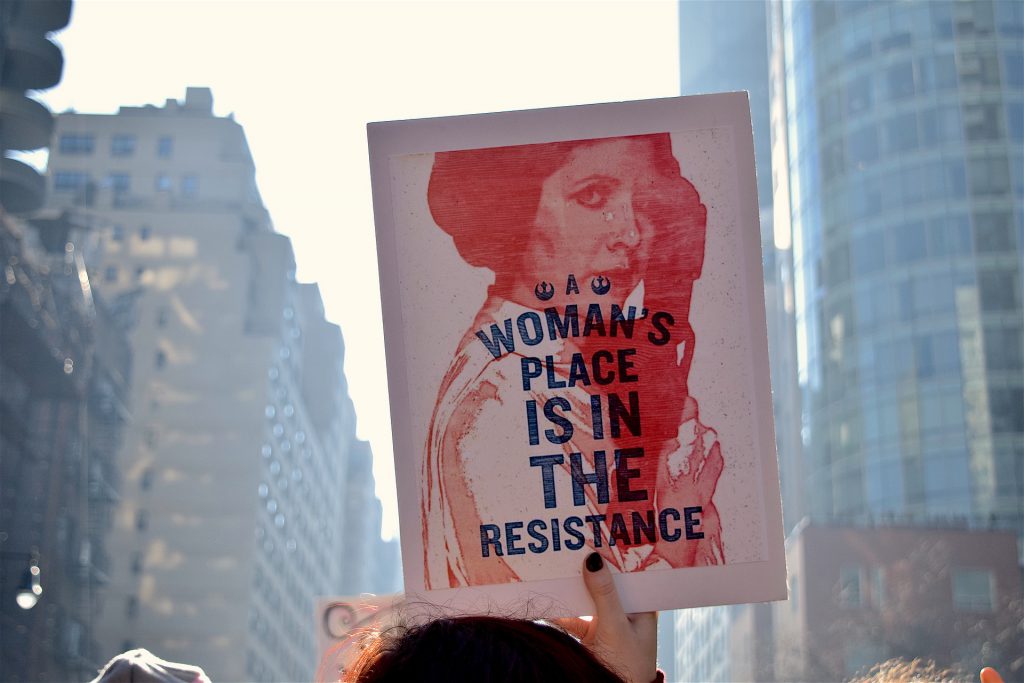

I have always believed that our institutions should seek to reflect the diversity of our community. So you might well be expecting me to bemoan the fact that there are still too few women inhabiting the secret cloisters of the national intelligence and security community, particularly in senior positions. And you might expect me to issue yet another appeal for a concerted attack on the glass ceiling.

You might also be expecting me to offer you all further encouragement in tackling the somewhat clubby character of the intelligence and security community which remains predominantly a male preserve.

There is no doubt that we need more women in the security business; equally, we need more women in leadership positions. So, more strength to your arm, collectively and individually, in your pursuit of equality. But what I want to focus on tonight is why women are so important in enabling our national intelligence and security community to meet the challenges that uncertain times bring with them.

There is a need for a careful reconsideration of what security is fundamentally about and whether our national responses to security issues are the most appropriate for uncertain times.

The paradigm change that may be necessary is only possible if the security community itself undergoes rejuvenation and transformation. One of the best ways to generate fresh thinking and innovation in any business is to ensure that gender equality and ethnic diversity are put to work to drive change.

Do we need to remind ourselves more persistently that we will not succeed or become safer by closing ourselves off from each other or from the world? Security challenges are best met working with others rather than turning inwards. And history reminds us of the risks that inward-looking, disengaged societies pose—risks of misunderstanding, tension and conflict.

Now I don’t claim expertise on these issues. What I can say, however, is that the concept of security for most Australians would also encompass economic and financial security, affordable health care, job and income security, quality childcare and the promise of a dignified retirement.

In other words, ‘security’ has a much broader connotation than the more threat-based protective and response concepts on which a lot of public policy concentrates. This in no way diminishes the work that you all do.

But what it might suggest is that a broader understanding of what security means for the general populace and where it impacts on people’s lives may in turn expand the range of tools at your disposal and the effectiveness of the programs you design and implement.

Disrupted times bring with them a raft of cares and worries. The French economist Thomas Piketty has identified economic inequality as a principal cause of the political instability currently infecting Europe—the Brexit vote and its currently unforeseeable consequences, the rise of radical parties on both the left and the right, the resurgence of nationalism in countries like Austria, Hungary and Poland, and the politics of exclusion on religious and racial grounds.

Into this mix come historical grievances driven in more or less equal parts by colonialism on the one hand and its collapse on the other. The picture becomes even more bleak when we see political leaders who reject the operating rules by which the international system has worked for the past seventy years, the emergence of new international players that want to impose new operating rules, and all of this rendered even more toxic by the emergence of nihilist ideologies that advocate death rather than tolerance.

Many of you would be familiar with the impact that discontinuity can have on complex systems. But complex systems generally have sufficient resilience to manage discontinuities, to bounce back relatively quickly. Indeed, many of the security features inbuilt into complex systems are specifically designed to deal with discontinuity.

Disruption is at the centre of the malaise that we see globally. Political and economic disruption are the main drivers of strategic disruption. It is that form of disruption that is undermining the confidence of people everywhere, generating care, worry and, more alarmingly, fear. And fear is particularly dangerous because it prompts irrational and dangerous actions.

You would all be aware of the call by many international commentators for governments to deal with the ‘root causes’ of the various forms of politically motivated violence presently affecting the global community. Of course, few of those commentators actually identify what those ‘root causes’ are.

But what we do know is that the so-called ‘root causes’ lie at the intersection of the economic, social, cultural, ethnic and ideological forces that lend movement and colour to human collective activity. And the agent who acts at the intersection of these forces is always an individual person.

In a thoughtful opinion piece published in the UK Guardian a couple of weeks ago, the novelist and former security specialist Nicholas Searle cautioned against rhetoric as a component of security policy.

Sweeping terms like ‘radical Islamic terrorism’ cannot alone explain the breakdown of law and order across the Middle East and that have spread their tentacles into Europe, North America, South and South East Asia, Africa and even Australia. It is interesting to note that the incoming National Security Advisor in the Trump administration, General H.R. McMaster, has also counselled against the use of terms such as ‘Islamic terrorism’.

Politically motivated violence is a form of criminal activity. It needs to be dealt with as such. And as an international phenomenon, politically motivated violence will best be contained and eliminated when nations, some of which are Muslim, work collaboratively to address the broad security needs of the communities in which the perpetrators live.

That kind of collaboration depends for its success on the ability to address the human security needs that condition fear and violence. That kind of collaboration will also serve to identify, detain and prosecute those who undertake politically motivated violence.

Rejuvenation and regeneration should always be front of mind for those who lead high-performing organisations. Subtlety and nuance in both policy and operations are most likely to be effective when organisations are truly representative of the communities they serve.

Open communities have the strength of inclusion. Closed communities have the spectre of fear.

Today marks International Women’s Day, so it’s a pertinent time to assess how Australia’s 2016

Today marks International Women’s Day, so it’s a pertinent time to assess how Australia’s 2016