Fremantle’s wartime past serves as AUKUS submarine prologue

The strategic potential of Submarine Rotational Force-West, the AUKUS initiative that commits the United States and United Kingdom to forward-deploy a small flotilla of nuclear-powered attack submarines to HMAS Stirling, near Fremantle, isn’t adequately appreciated.

Fortunately, history has set an instructive if insufficiently known precedent. During World War II, from a precarious start, Fremantle was a key base in one of the most effective sea-denial campaigns ever, hosting 127 American submarines, over 30 British boats and a handful of Dutch vessels. The parallels are revealing from various angles.

As with all things AUKUS, Submarine Rotational Force-West (SRF-West) has met criticism, including on the grounds that the offer to host foreign submarines at HMAS Stirling from the late 2020s supposedly undermines Australia’s sovereignty, even though the arrangement is on a rotational basis and modest in scale—starting with up to four American and one British nuclear-powered attack submarines (or SSNs).

SRF-West is nevertheless the main effort under AUKUS to bridge the Royal Australian Navy (RAN)’s looming submarine capability gap, as its six ageing Collins-class boats are progressively retired from the 2030s and before nuclear-powered replacements can be commissioned in numbers. As such, it is one of AUKUS’s potentially most impactful and within-reach initiatives, utilising Australia’s unique combination of positional advantage and strategic depth to maximise a key allied capability, wherein the US Navy (USN) retains a qualitative edge over China.

US and British submarines will further benefit from investment in new infrastructure, including a drydock, helping them to sustain a conventional deterrent presence from Australia efficiently. And if deterrence fails, SRF-West’s strategic potential will dramatically increase—in theory alongside a yet-to-be-designated east coast submarine base.

Astonishingly, Australia had no meaningful submarine capability of its own throughout WWII. This parlous state of affairs was the consequence of abortive attempts to recapitalise the submarine arm in the 1920s. During World War I, Australian submarines saw prominent action off German New Guinea and in the Dardanelles. Yet by the 1930s, a yawning capability void had opened up and remained unfilled even as Australia went to war with Germany, then Japan. This is a poignant echo of the contemporary policy failure to procure Collins’s successor in a timely fashion. The possibility that Australia could again end up with little or no submarine capability is not zero.

By the time Japan attacked Malaya and Singapore in December 1941, Britain had already pulled back most of its submarines to face the Axis threat in the Mediterranean. The closest British boats to Australia were in Sri Lanka. From March 1942, with Japanese forces poised to overrun the Philippines and all of Southeast Asia, Australia presented a last-ditch solution for the US Navy to disperse its submarines to safety while remaining forward deployed in the Western Pacific. The dispersal of US submarines to Australia from vulnerable bases in the first and second island chains is once again a contingency under active consideration.

From sketchy beginnings, still under fear of further Japanese attacks, Fremantle nonetheless emerged as the second-largest base for US submarine operations, after Hawaii, accounting for one quarter of the USN’s wartime patrols in the Pacific. Plans for a more northerly base, in Exmouth, Western Australia, closer to the theatre of operations across the Malay archipelago and South China Sea, were explored but abandoned. The USN also deployed 79 submarines from the east coast, at Brisbane. But Fremantle was the most popular base with Allied submarine crews and the most combat-effective.

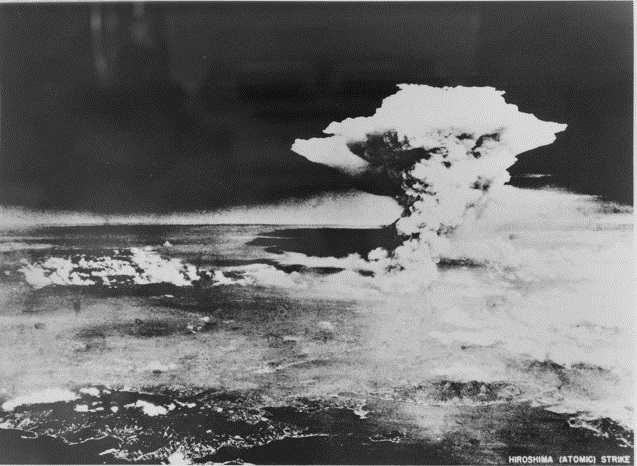

After a slow start, owing to competing mission taskings and poorly performing torpedoes the US submarine campaign in the Pacific only gained momentum in the second half of 1943. Crucially, however, the Americans had identified Japan’s merchant shipping and dependence on natural resources from Southeast Asia as the Achilles Heel in its war effort. During 1944, the US submarine campaign against Japan’s flimsily protected seaborne supplies turned into a rout. Fremantle-based boats led the charge.

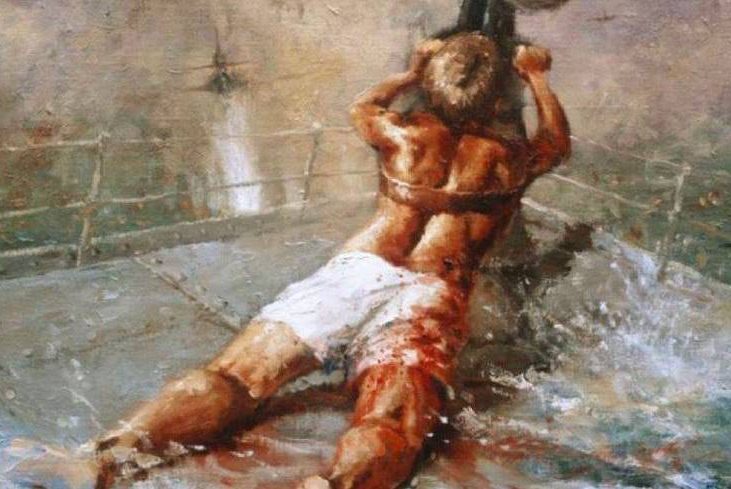

The submarine sea denial campaign—later augmented by aerial mining—was a pivotal factor in Japan’s defeat, a point conceded by its war cabinet. By early 1945, the inward flow of natural resources feeding Japan’s war economy and its outward military resupply effort had slowed to a trickle. This was achieved at a relatively low cost (eight submarines from Fremantle were lost out of 42 US boats across the Pacific), and substantially enabled by access to Australian bases.

From September 1944, with the Allies on the offensive in Europe, the British pushed forward their submarine operations against Japan to Australia. British patrols from Fremantle netted fewer strategic dividends than their American counterparts. Their smaller submarines still inflicted considerable damage, including against many light craft not recorded in the official statistics.

While the RAN lacked a sovereign submarine capability during the war, by making bases available to its closest allies Australia contributed to a collective endeavour that significantly hastened Japan’s defeat. Allied submarines operating from Fremantle, led by the USN, mounted 416 patrols and sank a total of 377 Japanese ships, surpassing 1.5 million tons. The tally of Japanese warships sunk from Fremantle included 19 destroyers, 16 frigates, 4 minesweepers and 9 submarine chasers.

The runaway success of Allied submarine operations from Fremantle and Brisbane, organised from scratch during Australia’s darkest hour, demonstrates the enduring value of Australia’s geography and its maritime alliances. Nuclear-powered submarines are far more potent than their WWII ancestors and are likely to be used for a variety of missions, but the wartime antecedent to AUKUS reaffirms the strategic rationale for contemporary deterrence efforts through AUKUS and SRF-West, while also underlining an urgent need for planning and preparation in the pre-war phase.

As with any historical parallel, the comparison has its limits. While the wartime example highlights the case for SRF-West as a gap-filler via external balancing, AUKUS shouldn’t be misconceived as offering a cargo cult-style remedy for home-grown deficiencies in Australia’s defence preparedness. Australia cannot afford to carry another submarine capability gap for the challenges ahead and must work to close it as soon as possible, as a whole-of-nation endeavour.