Sharing security interests, ASEAN’s big three step up cooperation

Southeast Asia’s three most populous countries are tightening their security relationships, evidently in response to China’s aggression in the South China Sea. This is most obvious in increased cooperation between the coast guards of the three countries – Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam.

But the three are moving closer together in bilateral arrangements, not as anything like a united trio. Going that far would be too damaging for their relations with China.

The obvious, though unstated, reason for collaboration is that all three have shared interests in a rules-based maritime order in the South China Sea. China’s widely disputed nine-dash line overlaps some territorial claims of Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei. China also claims that areas of Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone in the North Natuna Sea slightly overlap its claims.

Principally due to Beijing’s increasingly assertive behaviour in the region, there has been an escalation of military standoffs between China and each of Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam.

The three are members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, but the grouping has been unable to collectively act on territorial disputes in the South China Sea. Indonesia, Vietnam and the Philippines have instead found security cooperation on a bilateral level much more effective in advancing their domestic security interests. This is understandable as ASEAN is not a security alliance like NATO. Its principal focus and greatest success has been in economic development and trade.

For instance, amid the growing instability in the region, Jakarta has strengthened bilateral defence ties with both Manila and Hanoi. In 2022, Indonesia and Vietnam agreed to the boundaries of their exclusive economic zones in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Before the deal, they had overlapping claims in the North Natuna Sea.

In October, the Indonesian and Vietnamese coast guards jointly exercised off Ba Ria-Vung Tau, a southern Vietnamese province. The occasion also marked the first visit by an Indonesian coast guard ship to a Vietnamese port since a 2021 memorandum of understanding on maritime security and safety cooperation.

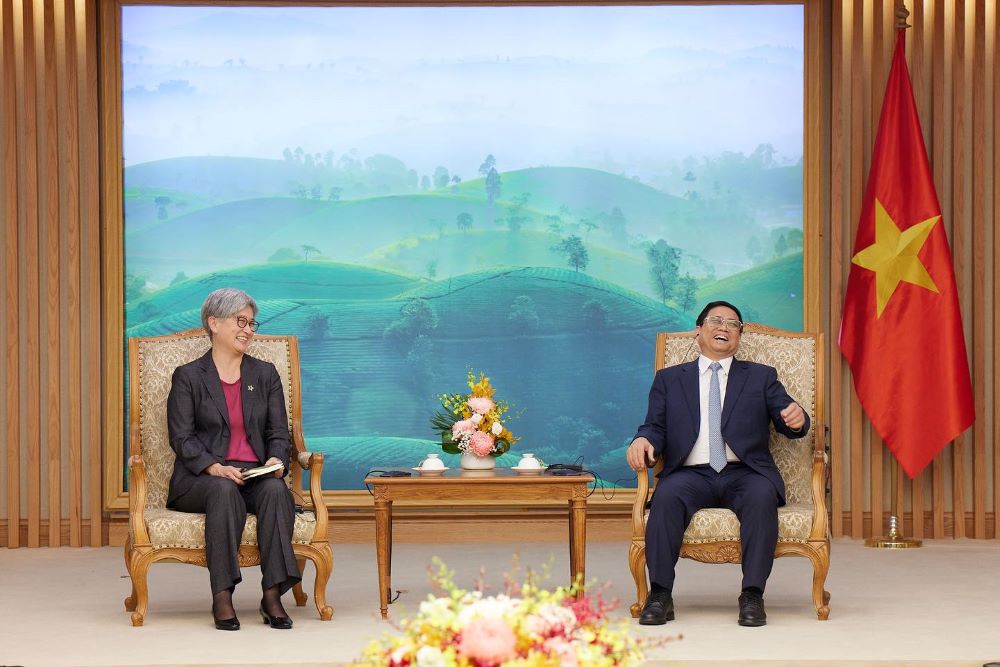

Last month the two countries elevated their ties to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership and committed to strengthening defence cooperation, particularly in maritime security.

Furthermore, Indonesia and the Philippines have deepened their security ties through the 2022 Indonesia-Philippines Defence Agreement. The Philippines and Indonesia run regular maritime border patrols in their respective maritime boundaries. In 2014, the two neighbours resolved their existing overlapping maritime claims under UNCLOS.

Working with Malaysia under a trilateral cooperative arrangement, Indonesia and the Philippines have run regular joint maritime patrols since 2017. This arrangement shows both Manila and Jakarta are willing and able to conduct a trilateral maritime cooperation with a third ASEAN country.

Also last month, the Philippines and Vietnam participated in the Indonesian navy’s annual multilateral naval exercise, Komodo, in Bali. In January, coast guard personnel from the US, Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines took part in a two-week maritime training course in Mindanao in the Philippines.

The Philippines and Vietnam have reinforced their maritime security awareness capabilities. Early last year, they signed a landmark maritime security deal. In it, Hanoi and Manila agreed to enhance maritime cooperation between their coastguards in the South China Sea, with a particular focus on working together to prevent and manage incidents in disputed waters.

However, the three countries may be reluctant to go as far as establishing a trilateral arrangement, because doing so could further provoke China, which now has the world’s largest navy. For instance, in 2023 China’s Nansha, the largest coast guard ship in the world, was sent to the North Natuna Sea. The incident occurred shortly after the Indonesia-Vietnam agreement on the boundaries of their exclusive economic zones. Some maritime security experts interpreted the deployment of the vessel as evidence that the new deal discomforted Beijing, which counts on intra-ASEAN divisions to prevent the emergence of a united front of claimant states against China over territorial disputes in the South China Sea.

Another major obstacle to such a trilateral arrangement could be the three countries’ significant economic relationships with China. China remains the largest trading partner for both Indonesia and Vietnam. It is also one of the Philippines top trading partners.

Nonetheless, the three strategic partners have accepted that they cannot leave it to ASEAN multilateralism to advance their shared security interests in the South China Sea. Deepening bilateral defence ties between the trio could be an incentive to build toward a united and effective trilateral maritime partnership.