The shape of Biden’s foreign policy

Joe Biden has been president of the United States for just a few weeks, but the central elements of his approach to the world are already clear: rebuilding at home, working with allies, embracing diplomacy, participating in international institutions and advocating for democracy. All of this puts him squarely in the largely successful post–World War II American foreign policy tradition repudiated by his predecessor, Donald Trump.

Delivering his first address on foreign policy from the State Department on 4 February, Biden declared, ‘America is back.’ He emphasised that Secretary of State Antony Blinken speaks for him and went to great lengths to support both America’s diplomats and diplomacy.

Biden also declared that he would stop any withdrawal of US armed forces from Germany, as Trump had ordered, presumably to help restore NATO members’ confidence in US security guarantees and to signal to Russian President Vladimir Putin that he shouldn’t try to use foreign adventurism to distract attention from domestic protests.

On Saudi Arabia, Biden walked a fine line. He distanced the US from military and intelligence support for the war in Yemen, explaining how US involvement henceforth would be diplomatic and humanitarian. At the same time, he made clear that the Saudis weren’t on their own in facing Iran. Squaring this circle will be far from easy, especially given the added complication of US disagreements with Saudi leaders over their poor human rights record.

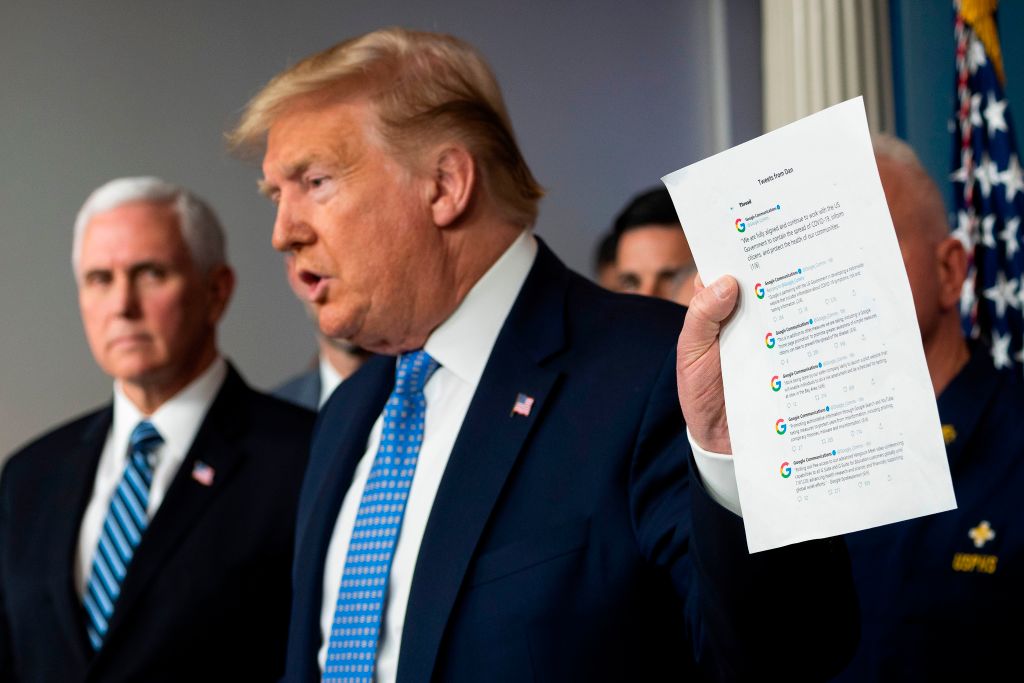

Biden’s ability to succeed in the world will be limited by several factors, many inherited. America’s capacity to be an effective advocate for democracy is much diminished in the aftermath of the 6 January insurrection at the US Capitol, and in view of the country’s polarised politics, endemic racism and Trump’s inept handling of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The good news is that progress on addressing the pandemic and its economic fallout is already visible. The bad news is that the country’s political and social divisions are certain to endure. Biden is fond of saying that America will lead by the power of its example, but it may be a long time before that example is one the world again admires.

Biden further reinforced humanitarian concerns by pledging to open the country’s doors to a much larger number of refugees. What could also help would be to make a significant number of doses of Covid-19 vaccines available to the developing world. This would be not only morally right, but also in America’s self-interest, as it would slow the emergence of mutations that threaten the effectiveness of existing vaccines. It would also help countries everywhere recover, leading to broad economic improvement and, ultimately, fewer refugees.

Although Biden is correct to criticise Russia and China for violating the rule of law, he can’t force their hands. Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping are prepared to pay the price of sanctions to maintain political control, and the US can’t hold the entire relationship with either country hostage to human rights. It must consider other vital interests, a reality underscored by the Biden administration’s decision to sign a five-year extension of the New START nuclear pact with Russia.

Similar realities (the need for help vis-à-vis North Korea just to mention one) will limit how much pressure the US can exert on China over its behaviour in Hong Kong or towards its Uyghur minority in Xinjiang. And even where Biden can place the rule of law at the centre of US policy—say, in Myanmar—he may discover that governments can resist, especially if they have outside help. All this raises questions about the wisdom of making democracy promotion so central to US foreign policy.

China policy will prove easier to articulate than to implement. Biden voiced strong criticism of Chinese behaviour, but also noted a desire to work with Xi’s regime when it is in America’s interest to do so. China will have to decide whether it is prepared to reciprocate in the face of US criticism, sanctions and export restrictions on sensitive technology.

The US will likewise encounter difficulty in realising its goal of organising the world to meet global challenges, from infectious disease and climate change to nuclear proliferation and conduct in cyberspace. There’s no consensus and no international community, and the US can neither compel others to act as it wants nor succeed on its own.

A good many difficult decisions remain. The Biden administration will need to determine what to do about Iran’s nuclear ambitions (and whether to re-enter the 2015 nuclear pact that many observers see as flawed). There are also questions about what to do with the accord signed a year ago with the Taliban—not so much a peace agreement as a cover for US military withdrawal—and about a North Korean regime that continues to expand its nuclear and missile arsenals.

However Biden’s foreign policy shapes up, it’s important that it be bipartisan and involve Congress when possible. US allies understandably fear that, in four years, Americans could return to Trumpism, if not the man himself. The fear that Trump wasn’t an aberration, but rather reflected what the US has become, undermines US influence. The temptation to govern by executive action is understandable, but when it comes to foreign policy, Biden should try to revive the principle that domestic politics stops at the water’s edge.