Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

US President Joe Biden has sent Congress his requested budget for the 2022 fiscal year. Due to the timelines of a presidential transition year, there’s not a lot of detail yet, but there’s enough to answer one big question in the strategic policy sphere: there won’t be a big change to the defence budget.

The document’s preamble states that ‘America is confronting four compounding crises of unprecedented scope and scale all at the same time.’ For those of us in the national security community, it’s a useful reminder of Biden’s priorities that China’s increasing power and aggression is not one of the four; rather, they are the pandemic, the resulting economic crisis, a ‘national reckoning on racial inequality centuries in the making’, and climate change. Competition with China is mentioned, but Biden makes clear that it isn’t simply or even mainly a military problem. Instead, he seeks to outcompete China through ‘a comprehensive strategy to reimagine and rebuild a new American economy’.

On top of that, Biden wasn’t exactly dealt a great hand in terms of cash in the bank. The budget request is only for discretionary funding. The bulk of the US federal budget is mandated or non-discretionary funding, which includes things like Social Security (retirement and disability benefits) and Medicare (health care for seniors). Over the past 35 years, mandated expenditure has grown from rough parity with discretionary funding to more than twice as much. In 2020 it blew out even further, to around three times as much, because of unemployment benefits and other support payments made during the pandemic (discretionary spending was around US$1.6 trillion and mandated was nearly US$4.9 trillion). With that, the annual deficit, which had been approaching US$1 trillion, surged past US$3 trillion. That also brought the public debt to US$21 trillion, or around 100% of GDP.

Within the discretionary budget, there’s been a rough 50–50 split between defence and non-defence spending. With most of the federal budget essentially untouchable, it might have been tempting for Biden to take the razor to defence spending to find the discretionary funds to support his domestic priorities. But he hasn’t done that. His discretionary budget request maintains an almost even split between defence and non-defence spending, despite his intent to reverse the long-term trend of declining non-defence discretionary spending.

The total defence request is US$753 billion, around US$12 billion more than President Donald Trump’s 2021 budget. Of that, US$715 billion is for the Department of Defense itself. In comparison, the rest of the discretionary budget, which funds everything else from energy to education, is only slightly more at US$769 billion. Defence spending is around 3.2% of GDP—far more than America’s allies, including Australia.

It’s a budget that probably disappoints the doves who want significant readjustment of spending priorities, and it’s about as good as the hawks could have reasonably hoped for.

The request acknowledges that more detail is to come. Even so, the lack of specifics around the Department of Defense stands out. While other departments’ individual programs are described with dollars attached, the DoD has only high-level language with no dollars. Whether that’s because issues such as health, energy and the environment are higher priorities, or because the administration hasn’t yet been able get its arms around the elephantine problems facing the DoD is not clear. But the discrepancy between the boilerplate language on defence and the sense of urgency and renewal in other areas is striking.

What is there on defence largely gives an impression of continuity. Countering the threat from China remains the department’s top challenge. There’s a commitment to ‘a strong, credible nuclear deterrent for the security of the Nation and US allies’. The recapitalisation of the ballistic missile submarine fleet—the US Navy’s most expensive program—will continue.

The Biden administration’s conviction that the means to manage competition with China are not purely military ones is evident in the document’s emphasis on rebuilding the economy and working with partners and allies. Importantly, the request includes a substantial increase to the State Department budget. But the need to deliver military capability is also real.

The administration seeks to ‘reimagine’ the economy, and elsewhere Biden has proposed bold ideas that affect all departments, such as putting climate change into their core planning. But there are few clear signs in this document of imagination at work in the administration’s plans specifically for defence. However, doing business the same way is unlikely to enable the US to counter the threats it perceives around the world.

The army, navy and air force all face major recapitalisation challenges, with fleets ageing out and the mounting cost of replacements simply unaffordable. Meanwhile, Chinese military power grows apace, reflecting its role as the world’s factory. China’s shipyards are pumping out ships at a rate the US can’t match. Trump’s defence secretary grappled for a year with the problem of how to design a navy that could counter China before delivering a plan that was essentially unaffordable and unachievable.

Biden’s administration will have to wrestle with the same challenges, and the lack of detail in the budget request suggests it hasn’t resolved where, or indeed whether, it will make fundamental changes. The boilerplate language leaves some room for manoeuvring. For example, it doesn’t sign up to a target for the size of the fleet, such as the 355 ships that have been an unattainable and arguably distracting goal for years. There are references to innovation and emerging technologies, such as ‘remotely operated and autonomous systems’ and hypersonics.

The request also refers to divesting ‘legacy capacity and force structure’. Again, this is standard boilerplate, but potentially offers cover for some large force structure decisions, such as reducing the size of the army to reinvest in the maritime and air assets needed in the Pacific.

Biden’s decision to follow through on the withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan suggests that he’s willing to make tough calls. One may not agree with the decision, but he broke with the status quo, even if the outcome is not clear. That decision will likely play well to a US public tired of ‘endless wars’, but it won’t by itself make much difference to the balance of power in the western Pacific. That will likely require a combination of more tough decisions and greater imagination than was revealed in this budget request.

On 26 February, the Paris-based Financial Action Task Force (FATF), a 39-country anti–money laundering and counter–terrorism financing watchdog, decided to yet again keep Pakistan on the ‘grey list’ for failing to complete the last three actions it had to take to be removed from the list.

This decision will have repercussions on US–Pakistan relations.

While the FATF president, Marcus Pleyer, noted that, since the last FATF meeting in October, Islamabad had made ‘significant progress’ in addressing the last three of the 27 action items assigned to it in June 2018, he stressed that there remained ‘serious deficiencies in mechanisms to plug terrorism financing’.

Pakistan is no doubt disappointed. Its foreign minister, Shah Mehmood Qureshi, appeared optimistic about the outcome of the meeting given that Pakistan had indeed taken some significant steps. In the past few months, the Pakistan authorities had arrested two top leaders of Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), the banned Kashmir-focused terrorist group that had been blamed by the US and India for the 2008 Mumbai attack in which more than 160 people were killed. Zakiur Rehman Lakhvi, LeT supreme commander, was given a five-year jail sentence for terror financing in January 2021 and Hafiz Saeed, the founder of the LeT, received a 10-year prison sentence in November 2020. Still, even with the arrest of these high-value terrorists, it’s unlikely that privately the government of Pakistan seriously thought it would be taken off the list.

According to Pleyer, Pakistan ‘must improve its investigations and prosecutions of all groups and entities financing terrorists … and show that penalties by courts are effective’. Once it has met these requirements, the FATF will reassess Pakistan’s eligibility to be taken off the grey list at its next meeting, in June.

The reason Pakistan is so keen to get a clean bill of health from the FATF is that being on the grey list limits Islamabad’s ability to access foreign funds to assist with its developmental and budgetary needs. It has been estimated by Tabadlab, an Islamabad-based think tank, that the listing has led to reduced household and government consumption, exports and direct foreign investment amounting to about US$38 billion.

Another direct consequence of being on the grey list since 2018 is that Pakistan has had to rely on the International Monetary Fund, Saudi Arabia and China to regularly bail it out financially. Pakistan simply cannot make ends meet on its own. However, by having to increasingly turn to China for its economic survival, in addition to the massive economic costs of the US$64 billion, 30-year China–Pakistan Economic Corridor project, Pakistan has reached a level of economic dependence on Beijing that is becoming irreversible.

However, China hasn’t bailed Pakistan out because of kindness. On the contrary, throwing a lifeline on a regular basis ensures that this nuclear-armed neighbour, with a population of over 220 million, doesn’t collapse economically. It is pure self-interest. But even more important, as part of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, the development of the port of Gwadar on the Indian Ocean, along with roads and other infrastructure that link Pakistan with the western province of Xinjiang, means that China effectively becomes a two-ocean state. Put differently, Pakistan is absolutely a force multiplier for China and therefore a Chinese asset worth safeguarding.

Pakistan’s now being solidly in Beijing’s strategic and economic orbits not only complicates Washington’s ability to manoeuvre in that critical geostrategic region, but also puts additional stress on the bilateral relationship at a time when President Joe Biden and his administration are trying to manage an honourable exit from neighbouring Afghanistan.

Washington recognises the important role Islamabad played in getting the Taliban to sign up to the February 2020 peace deal and the role it continues to have in the now deeply troubled Afghan peace process. This was reaffirmed by the new secretary of defence, Lloyd Austin. However, if Biden decides not to withdraw the remaining 2,500 military personnel from Afghanistan by 1 May, as the US is meant to according to the peace agreement, the impact on US–Pakistan relations will be very serious. Once again, Islamabad will feel let down by the Americans. However, despite that, Washington is unlikely to resume military aid to Pakistan of around US$1 billion annually which was suspended by President Donald Trump in 2018.

But an even greater stress point for US–Pakistan relations is America’s ever-deepening relations––military and economic––with India, Pakistan’s nemesis since partition in 1947. Austin reaffirmed that under his watch he would seek to ‘further operationalise India’s “major defence partner” status and continue to build upon existing strong defence cooperation’. Not surprisingly, this will inevitably push Pakistan even deeper into China’s orbit.

While Biden may have been interested in making a new, clean start of sorts with Islamabad, he is no longer in the mood for that following the Pakistan supreme court’s recent decision to uphold a lower provincial court’s ruling to release Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, who had been acquitted of any involvement in the beheading of Daniel Pearl, a Wall Street Journal reporter, in 2002. This has seriously upset the Biden administration.

So, what does Pakistan need to do to regain America’s trust on the counterterrorism front? Despite the Pakistan government’s arrest of several high-profile terrorist leaders, however, there’s a nagging perception––justified or not––that the country remains a nest of terrorists supported in some cases by the military. It’s critical for Islamabad to dispel this perception. To start with, it needs to arrest some of the remaining terrorist leaders, in particular Masood Azhar, the leader of the banned, Kashmir-focused Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM), and other fellow ideological followers. There are indications that the Pakistan government is indeed considering taking action against the JeM.

If Islamabad did arrest and hand down long prison sentences to some of the remaining terrorist leaders, it would certainly help put the US–Pakistan relationship on a stronger footing and give a real boost to Pakistan’s chances of finally being taken off the grey list when the FATF meets again in a few months. Not to do so would be a very serious mistake indeed.

The US Navy’s new low-yield submarine-launched ballistic missile, produced rapidly by the National Nuclear Security Administration, is intended to provide a proportional response to US adversaries’ concepts of ‘coercive, limited nuclear escalation’.

Proposed in the Trump administration’s 2018 nuclear posture review, the SLBM incorporates a variant of the W76-1 warhead called the W76-2 and lowers the explosive yield from 90 kilotons to an estimated 5 kilotons. The missile has been deployed on Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines.

Concern over Russia’s potential to use non-strategic or tactical nuclear weapons against NATO members demands that the US have a response other than high-yield weapons.

Until now, the US’s options were limited. Responding to Russian threats to use low-yield non-strategic nuclear weapons with a 90-kiloton nuclear warhead would be disproportionate and an adversary might well consider it not to be credible. Although the US fields the B61 low-yield gravity bomb and recently developed the B61-12, the aircraft carrying these non-strategic weapons would need to navigate advanced Russian integrated air defences to reach their targets. That raises doubts that high-yield warheads are a viable option.

Credible deterrence that reduces the risk of use of nuclear weapons requires credible responses. The low-yield SLBM is an additional deterrence measure designed to prevent war, not make it more likely.

President Joe Biden has inherited a situation where great-power competition will have significant global consequences and appropriate signalling to potential adversaries is critical for preventing war. During the election campaign, Biden signalled that he believed the deployment of the low-yield SLBM was a ‘bad idea’. He has also publicly supported a ‘no first use’ nuclear policy. A key presidential adviser, Bonnie Jenkins, has also advocated no first use. Jenkins has been nominated as Biden’s undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, which would place her in a strong position to influence this policy.

The increasingly aggressive behaviour of China and Russia, the risk that Iran will develop a nuclear arsenal and North Korea’s possession of intercontinental ballistic missiles make the world more dangerous and volatile. Biden needs to signal that all options are on the table when it comes to defending the US, its allies and its interests and that these options are dynamic, versatile and fit for purpose.

In the face of China’s nuclear modernisation, the US can’t afford to take options off the table and signal a weakness of resolve. In her 2016 book on Chinese nuclear proliferation, Susan Turner Haynes says China is moving away from a minimum deterrence nuclear strategy to one of limited deterrence. Her analysis is based on Chinese military documentation and the quantitative and qualitative modernisation of China’s nuclear structure, which suggests a progression to a warfighting nuclear capability.

The study also casts doubt on the likelihood of China adhering to a true no-first-use policy. Beijing’s long-term commitment to this policy has also been questioned by analysts including retired People’s Liberation Army major general Zhenqiang Pan, who stated: ‘China’s new strategic goal of achieving a most influential world power status by the mid-twenty-first century may envisage a greater role of its military force, including the role of nuclear weapons, and perhaps the need to revisit its no-first-use policy.’

Turner Haynes describes a number of differences between minimum deterrence and limited deterrence, but one distinction goes to the heart of the issue. She says that ‘minimum deterrence is achieved by having the ability to strike back after a first strike’, while ‘limited deterrence is achieved by increasing nuclear options’. For Biden to signal an intention to decrease the US’s nuclear options such as the low-yield SLBM in the face of determined nuclear modernisation by great-power competitors sends a dangerous signal.

His comments may prove to be rhetoric intended to appeal to his base, which includes nuclear abolitionists and the arms-control community, and the president may leave the nuclear policies and structure in place. But the issue is the power of the message.

With a new president signalling that nuclear weapons are not an option, aggressive dictators looking to exploit power vacuums and weakness may conclude that the time is right to push the envelope and invade Taiwan or close the South China Sea, invade the Baltic States or attack South Korea.

US nuclear policies and strategies have helped prevent great-power conflict through appropriate signalling and a robust, evolving nuclear posture. Now is not the time weaken our resolve when bullies are seeking to exploit global fear and hardship and gain an advantage. Let’s not be blindly idealistic to the point of weakening solid defence structures. There’s too much at stake.

Biden needs to signal to potential adversaries that the US has developed and produced flexible options for a reason, and that these options can and will be used proportionally.

An impeached president departs Washington in disgrace. The peace deal in America’s longest war crumbles and defeat looms.

US politics is polarised. A nation, both angry and agitated, grapples with racial and social divisions.

The superpower rival jeers at America’s agonies, gloating that its system works better.

Other democracies offer sympathy as they debate America’s decline. Aghast at America’s travails, Europe seeks its own way, affirming the different values of the great European project. The old US ally, Britain, takes a historic European leap.

Asia wonders what life might be like without the US hegemon. Australia pledges enduring faith in the US alliance while gazing at Asia, frantically assessing how much American power has ebbed.

These are scenes from history, not today’s headlines—moments watched long ago on a small black-and-white TV.

Behold, 1974: a tough and trying time for the US.

I match those black-and-white analogue memories to today’s vivid, digital colour. Much does repeat in this rhyming history. Or as Mark Twain actually expressed it: ‘History never repeats itself, but the kaleidoscopic combinations of the pictured present often seem to be constructed out of the broken fragments of antique legends.’

In 1974, the disgraced president was Richard Nixon. The longest war was Vietnam. The rival was the Soviet Union. Britain was joining, not leaving, Europe. Australia had interred the White Australia policy and turned towards a new destiny as a multicultural nation that found its security in, not from, Asia.

The then-and-now effort is a way to loosen the grip of living in this extraordinary moment (the tyranny of the present). Other times have been just as extraordinary, and some history reads as a rerun.

One difference is that as a young journalist in 1974 I was far more pessimistic about America’s prospects than today’s greying hack. The US can still amaze on the upside, just as it can appal on the down.

All those decades of gazing as an outsider at the ever-roiling drama that is America teaches a lesson of vigour and resilience and imagination. It’s the not-so-secret sauce that makes democracies powerful: switch a leader and swiftly change course.

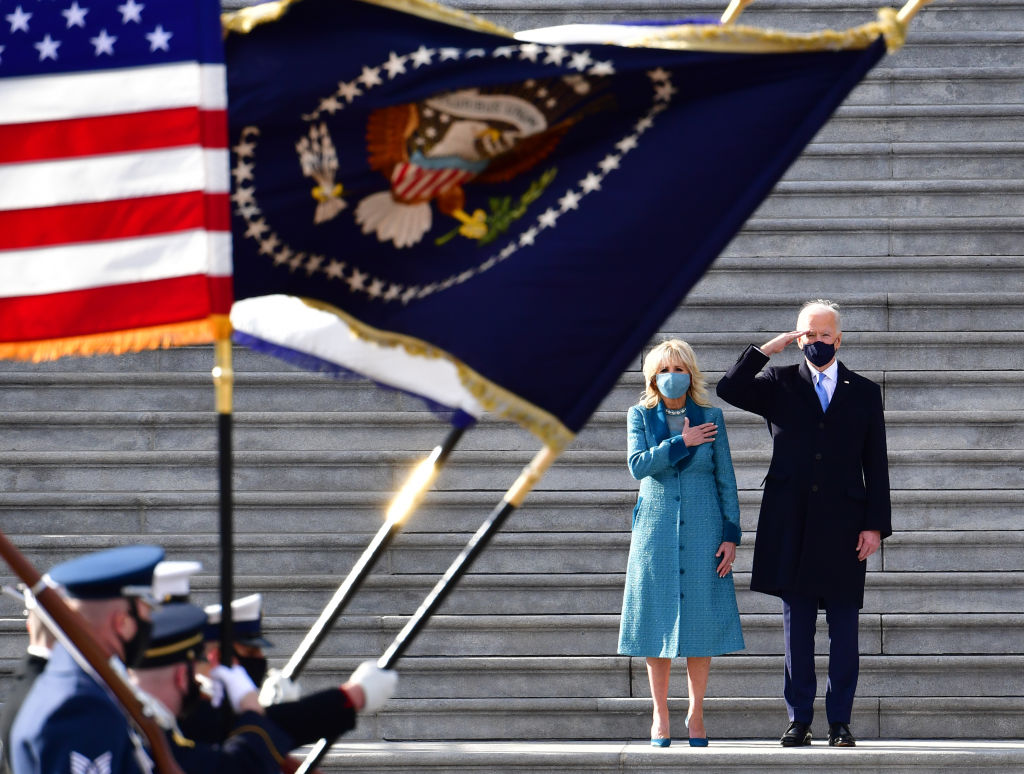

Amid turmoil, the US system has just worked its magic, disposing of an incompetent president who governed with a whim of iron, or perhaps a will of irony.

As always, America did the deed in full public view while arguing passionately (other elements of the voters’ recipe). The troubles that beset democracies always contain the seeds of recovery.

The 1974 comparison crashes against Covid-19. The pandemic makes today’s moment feel unique and singularly important (classic tyranny-of-the-present stuff). Yet a touch of ’70s angst flavours the lament that the Covid year was very bad for global democracy.

Afghanistan replaces Vietnam as the longest war. And now there’s another fragile peace deal. Heading for the exit in Afghanistan, the Biden administration is haunted by that image of the last helicopter fleeing the roof of the US embassy in Saigon.

These days China is the rival power crowing about the US as ‘a wheezing superpower in denial about its decline’. President Joe Biden’s language and some of his tactics will be different from Donald Trump’s, but Washington’s new grand strategy is set: to compete, challenge and compel China.

The Cold War analogy is misleading, even unsafe, not least because we know how the last one finished. Fifteen years on from the 1974 low point, the US burst free of the bipolar freeze to bask in the triumph of its ‘unipolar moment’. Reusing the old Cold War label can feed the assumption that the previous script will recur and the US must repeat its triumph.

Be confident about the US while understanding the caution in Twain’s truth: history only rhymes. This is more hot peace than cold war. The US and China are as intertwined as they are opposed.

Xi Jinping’s Davos speech used the ‘cold war’ descriptor three times, including this warning: ‘To build small circles or start a new Cold War, to reject, threaten or intimidate others, to wilfully impose decoupling, supply disruption or sanctions, and to create isolation or estrangement will only push the world into division and even confrontation.’

Xi’s remark about strong states that bully gets a nod of agreement from Canberra. Australia has been talking openly about China as a bully and its potential as an adversary. Our icy age with China is about to enter its fifth year.

Reflecting on that icy experience in his National Press Club speech last week, Prime Minister Scott Morrison offered this judgement on the China relationship: ‘We cannot pretend that things are as they were. The world has changed.’

The PM could have applied the same thought to the US: much has changed; there’s no going back.

As Biden says, the ‘credibility and influence of the United States in the world have diminished’. The new president’s aim for America to lead again confronts multipolar complexity.

Much of the contest in coming decades will be between ‘techno democracies’ and ‘techno autocracies’, the vision offered by the new secretary of state, Antony Blinken, in his confirmation hearing (‘outcompete China’ and ‘revitalize core alliances’).

The democracy element of that equation delivers much. The optimism of rhyming history shows that America has been here before.

The attack on the US Capitol on 6 January has been interpreted in multiple ways. The most common interpretation asserts that President Donald Trump’s narcissistic obsessions and highly inflammatory rhetoric were responsible for the sordid events of that day. A second interpretation attributes the mayhem to the high degree of party political and ideological polarisation in the country. Economic uncertainty and distress caused by the Covid-19 pandemic is cited as another major factor contributing to anarchy and political breakdown.

There’s truth in each of these assertions. But all of them discount the elephant in the room, namely, the deep sense of anxiety, indeed apprehension, felt by a sizeable portion of white Americans that their patrimony is being stolen from them. This deep-seated angst was why Trump’s assertions that the election had been ‘stolen’ from him touched such a sympathetic chord in so many. It also lies at the heart of the anti-immigration sentiment in the country that Trump stoked time and again both before and after taking office.

Trump’s nihilistic rhetoric and false claims only accentuated an underlying fear whose main cause has little to do with economics or political ideology and much to do with race. The predominantly white composition of the crowd that attacked the Capitol, chanting for the reclamation of their birthright and for the blood of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Vice President Mike Pence, whom they consider traitors to their cause, is clear testimony to this fact.

Whites constituted about 73% of the American population in 2017. But if one excludes Hispanic whites, most of whom identify as Latino rather than white, the proportion falls to 61%. It’s expected to fall below 50% by 2045 as a result of immigration and low birth rates. The anti-immigration and militantly white supremacist attitudes of many Trump supporters is a product of their fear of becoming a numerical minority—a feeling that Trump plays to with his virulent anti-immigrant rhetoric.

To white supremacists, Barack Obama’s election as president in 2008 and again in 2012 was a turning point; it seemed to signal the end of the US as a ‘white’ country and spawned the ‘birther’ movement, of which Trump was a part, that sought to discredit Obama as foreign born. Now, the election to the highest office of Obama’s vice president, Joe Biden, who’s seen as the inheritor of Obama’s political legacy, with African Indian American Kamala Harris as his deputy, has further increased the apprehension among a segment of white Americans that they are being deprived of their rightful place in the pecking order in the United States.

A dramatic increase in the African American voter turnout in the presidential election has added to those fears. The fact that black voters determined in large part the outcome of Georgia’s Senate runoffs on 5 January that led to the Republicans losing both seats has further enhanced the sense of ‘disenfranchisement’ harboured by sections of the white population. The prominent display of Confederate flags during the attack on the Capitol, confirms this conclusion.

Trump’s refusal earlier in the year to categorically condemn white supremacist groups and their attacks on Black Lives Matter protestors emboldened these elements no end. It’s a shame that the party of Abraham Lincoln has for the past four years been colluding with white supremacists, propagating their racist ideology and undermining the foundations of America’s constitutional democracy in order to achieve ephemeral gains. The backlash the party faces following the domestic terrorism of 6 January demonstrates the counterproductive nature of this strategy.

All these signs suggest that support for Trump’s fabricated claims is largely a product of the anxiety that the US is changing ‘colour’. In this sense it is a rerun of the scenario preceding the Civil War. One of the main drivers of that conflict was the threat that the emancipation of black slaves was seen to pose to white privilege. Let’s hope matters don’t reach the point of no return as they did in 1861 and that this rush to the precipice will be halted and reversed before it’s too late. A second impeachment of Trump is essential to bring the US back to its much-vaunted constitutional roots.

There’s much talk in Washington these days about the relative merits of accountability versus healing. This is a false dichotomy. Both can take place, simultaneously reinforcing each other. But for that to happen, it’s imperative that the Republican Party take the lead on both counts—by holding Trump accountable and by reaching out to the Democrats.

Only then can America’s body politic begin the process of healing from the severe wounds inflicted by a Republican president enabled by a collaborating GOP leadership several of whose members outpaced the president in their inflammatory rhetoric.

May wisdom finally dawn on Republican leaders in Congress and in the states that they must take responsibility for the horrendous mistakes that culminated in the attack on the Capitol and that they need to make amends for their errors quickly.

Originally published 26 May 2020.

There’s a big international weapons program that probably doesn’t pass the post-coronavirus pub test for supply chain security. As US President Donald Trump’s recently said, ‘It’s a certain fighter jet, I won’t tell you which, but it happens to be the F-35.’

Trump’s musings about making all components for the F-35 in the United States might have been only a thought bubble, but they also brutally revealed the internal contradiction at the heart of calls to mitigate supply-chain vulnerabilities by bringing production back on shore: one person’s local manufacture is another’s loss of export markets and workshare.

There are a couple of reasons why Trump’s idea of stripping the seven remaining non-US partners in the joint strike fighter consortium (Australia, Canada, Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway and the United Kingdom) of their workshares likely won’t happen. The first is that finding new suppliers for literally thousands of components will inevitably delay the program even further. Replacements for all of the components made by Turkey still haven’t been found, even though the program has had a year and a half to work through the consequences of ejecting Turkey.

The second is that it would be an act of perfidy that would be hard for America’s allies to ignore. The other six consortium members are in NATO, which has already been buffeted by Trump’s treatment of allies. Those six have been in for the long haul, literally paying their consortium dues in the expectation of significant workshares. They are anticipating a substantial return on that commitment with production ramping up now. Plus, they have expectations of feeding parts into the sustainment supply for the next 40 years.

The Europeans generally have much higher expectations of industrial offsets than Australia does, so they would be outraged if Trump’s idea became a reality. They might even think of leaving the program and buying a different aircraft. But Trump has them over a barrel—the UK and Italy need the F-35B short take-off and vertical-landing variant for their aircraft carriers and there’s nothing else on the market. Those who are buying the conventional F-35A variant could look to the Eurofighter or something else, but their F-35 deliveries have already begun so there’s a huge sunk cost in changing course.

Australia’s workshare is also at stake. Let’s put aside the fact that there’s no public evidence for the widely repeated figure of 5,000 Australian jobs in the F-35 supply chain. That would be about the same number of jobs as will be directly involved in building the future frigates and submarines, so it also doesn’t pass the pub test. Independent analysis suggests 1,000 is a more reasonable number. Nevertheless, there is a principle here, not to mention contracts.

The allies’ sense of betrayal and the blow to US credibility should be enough to stop Trump going through with it.

But Covid-19 is forcing the world to challenge its assumptions, and that raises the question of whether you would design a program like this again. Deliberately scattering bits of manufacturing supply chains around the world goes against the post-Covid-19 wisdom of consolidating to ensure greater control.

The F-35 sustainment system also prevents participants from stockpiling their own spares for a crisis. All spares are owned and held by the program and are warehoused around the world. If you need them, you have to rely on a just-in-time model to deliver them—except the model doesn’t work anywhere near as well as we’ve come to expect from companies like Amazon, even in peacetime. So, you have to order your just-in-time spares two years in advance. The ‘autonomic logistics information system’ that is meant to understand and manage demand for spares is so clunky the US Department of Defense is junking it and starting over with a (hopefully) better one that doesn’t rely on 1990s software and is designed from the outset to operate in the cloud.

Australia will be a regional repair and warehousing hub in the current JSF model; hopefully Defence has done its due diligence to test whether that model with withstand the demands of wartime use. Nevertheless, Australia still can’t own and stockpile its own spares even if it wants to spend the money.

But more than this, there’s the sheer size and complexity of the program. Granted the aircraft is now more or less doing what it’s meant to do and is delivering unmatched capability. But the amount of developmental technology involved, the level of systems integration, and the amount of software to make it all work has also meant long delays, huge cost increases and a lack of agility.

The program has been going for 19 years and still hasn’t received sign-off to start full-rate production. Those delays mean it’s hard to plan transitions and legacy platforms stay in service longer. It also means you don’t enjoy the benefits of that unmatched capability for as long as adversaries have time to develop counter-technologies. The complexity means that individual consortium members can’t simply develop the upgrades they need, which is why Australia is still waiting for its priority capability—an integrated long-range maritime strike weapon. It also means sustainment costs are nowhere near the original aim of being comparable to those of the aircraft being replaced.

In contrast to the JSF behemoth, look at the little country that could. Sweden, with less than half the population of Australia, is one of the few countries left in the world that can design and build fighter planes (and submarines, warships, missiles and armoured vehicles, for that matter). There are only around 250 of Sweden’s Gripen fighter in the world compared with the more than 3,000 planned F-35s, but it still seems to be cost-effective to make them.

This isn’t to say we should abandon the JSF program and buy Gripens. But it does suggest we also should be exploring other models to develop and acquire military capability. Models that can deliver ‘good enough’ capability faster, that we can evolve ourselves to meet our priorities, and that we can support, repair and upgrade in a crisis are worth taking a look at in the post-Covid-19 world.

US President-elect Joe Biden’s income-redistribution and green-energy programs are set to be eviscerated by the US Senate, even if the Democrats gain a spare majority by winning both Senate run-off races in the southern state of Georgia.

The elements of his economic agenda most likely to survive are those with a protectionist flavour that could be supported by at least some of the Republican backers of outgoing President Donald Trump.

Biden went to the election promising to boost spending on social and environmental programs by US$5.4 trillion over a decade while raising an additional US$3.4 trillion in additional taxes aimed exclusively at top income earners and corporations.

It was not as wild as the US$30 trillion spending plan developed by former Democratic rival Elizabeth Warren or the US$40 trillion proposal of the other radical contender Bernie Sanders. But the Biden plan was calculated to keep the supporters of both those campaigns onside and voting.

Biden promised his administration would expand the coverage of President Barack Obama’s healthcare package while introducing free and universal pre-kindergarten education, minimum family paid leave and big boosts to social security and housing initiatives.

The election policy set a target of carbon-neutral US electricity generation by 2035, to be achieved by US$2 trillion of targeted spending initiatives, rather than through a carbon tax.

To partially offset these costs, the Biden team promised to raise the company tax rate from 21% to 28% and introduce a minimum company tax rate of 15% for businesses with incomes over US$100 million. There would be a penalty payroll tax on incomes above US$400,000 and an increase in capital gains tax.

There is no prospect of the Republicans supporting these tax increases. The president has some latitude to use executive orders to redirect spending and Biden will use that tool, but it won’t yield enough to finance a program of the ambition outlined to voters.

If the Democrats win the two run-off Senate elections, to be held on 5 January, the Senate will be split evenly with 50 seats each for the Democrats and Republicans, in which case Vice President Kamala Harris would have the deciding vote, delivering a Democratic majority.

However, it takes a 60% majority to force a US Senate vote on major tax and spending bills. Without it, the opposition can keep on debating in a filibuster until the proponents give up.

The only obvious wriggle room is provided by the Senate’s ‘Byrd Rule’, which allows three pieces of legislation to be passed each year with a simple majority, with one covering tax, another spending and the third the debt ceiling, with the proviso that they aren’t allowed to generate a lasting increase in the deficit.

If the Democrats win only one of the Georgia Senate seats, they will lack even a simple majority and will have to rely on luring Republicans to get anything through.

The Trump administration used the Byrd Rule to pass its tax reforms in 2017, so it can be used for radical measures. However, it will come down to what the Biden administration decides to prioritise.

Lifting the company tax rate is unlikely to be close to the top of the list, regardless of what happens with the Georgia vote. However, a border levy on the goods of countries with high carbon emissions could be.

Biden has described climate change as ‘the number one issue facing humanity’ and his climate policy suggests ‘carbon adjustment fees’ may be imposed on imports. Since a border tax would principally target China, it would have some Republican support.

The European Union is developing a border carbon tax that would target goods from nations that don’t have concrete plans to achieve carbon neutrality. There’s some risk to Australian steel and aluminium exports to both Europe and the US in the absence of a more forthright carbon mitigation policy from the Australian government.

Biden also advanced a set of ‘Buy American’ policies that had Trump complaining of plagiarism. These include a proposal to require US$400 billion in government procurement to favour US firms. Such a policy would, at first glance, contravene World Trade Organization requirements. Biden has said he would work with allies to reform the trade rules, saying it should be possible for the government to dictate that taxpayers’ dollars are spent in their own country.

Another proposal with a strongly Trumpian ‘America first’ flavour is to introduce a 10% surtax on imports from firms that had shifted manufacturing away from the US. This would be matched by a 10% ‘Made in America’ tax credit for companies bringing offshore manufacturing back to the US. While measures like these may win bipartisan support, they are novel tax law and may take time to design and implement.

One of the reasons Biden won the Democratic nomination was because he was seen as the best chance to win back the working-class voters in the mid-western manufacturing heartland who had deserted the Democrats for Trump in 2016.

Biden was indeed successful in winning back Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin but will be beholden to manufacturing lobbies in those states.

It’s difficult to envisage Biden investing much of his political capital in joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership, which was formed at the initiative of Japan and Australia after Trump pulled out of the original Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiated by the Obama administration.

One element of the tax plan that Biden took to the election which may survive in some form is a proposal to strengthen the treatment of company profits recorded in tax havens. Biden proposed doubling the special tax on global intangible low-tax income to 21% and preventing companies from averaging their global profits.

These measures would be consistent with the OECD’s efforts to strengthen tax collections from global companies and would forestall European nations from pressing ahead with special taxes on the (mainly US-based) digital services companies.

With the US presidential election drawing to a close, everyone, it seems, is absorbing the lessons from the surprising 2016 contest.

Pollsters, largely blamed for failing to foresee President Donald Trump’s stunning victory last time, have been busy tweaking their turnout models, adjusting their survey samples and warning that a potential ‘hidden’ Trump vote could skew all projections.

Democrats, scarred by the memory of Hillary Clinton’s shocking 2016 defeat, are gaming out all the scenarios for how former vice-president Joe Biden might still lose or how Trump might cheat his way to victory. And Republicans, buoyed by the result four years ago, are largely ignoring the bleak polls and touting their superior ‘ground game’ to get likely Trump supporters to the voting booths.

The memory of the 2016 election has also altered the way journalists covered this year’s race, producing some long overdue changes while raising questions about the proper role of the traditional, or legacy, media in the hyperkinetic digital news cycle.

First, television networks no longer provide live coverage of Trump’s raucous campaign rallies. During the 2016 campaign, those rollicking red-draped rallies—with Trump supporters in ‘Make America Great Again’ caps chanting ‘Lock her up!’ and ‘Build that wall!’—were staples of cable television, and for Trump amounted to free airtime. Now, the rallies are covered live only by Fox News, whose viewers are already the president’s faithful.

Starting in 2015, when Trump descended the escalator in his gold-plated Trump Tower and announced his candidacy, the media treated ‘The Trump Show’ as an entertainment bonanza that captured audiences’ attention and boosted ratings and clicks. Journalists who covered political campaigns had never encountered anything like the smash-mouth, smack-talking New Yorker who insulted his rivals with belittling nicknames (‘Little Marco!’, ‘Lyin’ Ted!’), boasted of his own super-genius and touted his poll numbers more than any coherent policies.

Trump, who became a star of reality television playing the role of a braggadocious billionaire shouting ‘You’re fired!’, played to the audience, and the media became his enablers. This time, no longer.

Second, journalists have become more willing to call out Trump’s untrue statements as lies, including to his face when he sits for interviews outside his Fox News bubble.

In 2016, journalists were caught flat-footed and unable to respond to a politician—much less a presidential candidate—who made statements that were demonstrably false. In established newspapers like the New York Times, the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal, it was considered uncivil to use the word ‘lie’, since that implied intent to deceive on the part of the speaker.

In September 2016, the New York Times caused major media shockwaves the first time it used the word ‘lie’ in a headline, about Trump’s repeated peddling of the debunked conspiracy theory that former president Barack Obama was not born in the United States. The use of the word ‘lie’ was seen as crossing a journalistic Rubicon, and the headline was the source of a lengthy defence by the Times’ public editor, the executive editor went on the air to explain it, and media analysts spent weeks debating it.

Since then, Trump’s presidency—and his avalanche of untruths—has caused a rethinking in the media. His lies are now called out in real time, and journalists have dispensed with some of the traditional niceties to give readers and viewers a more accurate picture with real-time fact-checking.

It began immediately in Trump’s first year in office. When top Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway used the term ‘alternative facts’ to describe her reality-challenged talking points, a CNN chyron offered a direct rebuttal: ‘“Alternative facts” are lies’.

This year, during one of the White House televised briefings on the coronavirus pandemic, a CNN chyron declared, ‘Angry Trump turns briefing into propaganda session’. Another read, ‘Trump uses task force briefing to try and rewrite history on coronavirus response’.

The few times Trump has ventured out of his Fox News media comfort zone to be questioned by hard-nosed journalists, the president has found himself challenged in real time for his lies, exaggerations and distortions.

When Trump tried to get away with telling Axios reporter Jonathan Swan that the reporter didn’t know the real coronavirus death toll in South Korea, Swan shot back, ‘I do!’ When Trump insisted to 60 Minutes veteran correspondent Lesley Stahl that he had built the greatest economy in history, she replied bluntly and accurately, ‘That’s not true.’ Trump was so flummoxed and angered he cut the interview short.

Even the social media giants have, belatedly, become wiser, blocking some of Trump’s posts that they say violate their standards and peddle inaccurate information. For example, Facebook and Twitter in October took action against misleading Trump tweets saying the Covid-19 disease was less lethal than the common flu. Facebook removed it entirely and Twitter moved it behind a note saying it violated the company’s policy against disinformation.

Critics—mostly Trump supporters and conservative activists—complain that journalists and social media companies should not be the arbiters of truth, and that their calling out of Trump’s statements, or deleting his posts, amounts to a form of censorship. I believe such truth-telling is long overdue.

The media’s third big lesson this campaign cycle is that, unlike in 2016, journalists for mainstream outlets have shown a welcome new discipline in not taking and amplifying the unfounded conspiracy theories that swirl around in the Fox News and social media swamp.

Four years ago, the most baseless right-wing conspiracy theories often made their way into mainstream media publications—that Hillary Clinton’s emails contained incriminating information, that she had committed serious crimes or was suffering from a hidden, debilitating illness, and that the election was being rigged. Often, reputable publications were merely reporting the existence of the theories. But even repeating them added traction, and likely confused voters as to what was true and what was false.

Now the media has resisted following the breathless reporting in the tabloid New York Post and on Fox News—both owned by Rupert Murdoch—that newly unearthed emails allegedly from Biden’s son Hunter and supposedly found on a laptop contain evidence of malfeasance implicating the Democratic candidate. Trump and his allies have become angry and frustrated that legacy media have rightly given the story a pass, robbing them of an ‘October surprise’ scandal.

Finally, the media this cycle appears to have dispensed with the notion of creating false equivalencies.

In 2016, journalists’ concern with maintaining objectivity meant that most articles about Trump’s financial entanglements and his refusal to release his tax returns included the requisite paragraphs noting concerns about foreign donations to the Clinton Foundation. Stories about Trump’s history of making degrading comments about women—including his recorded remarks bragging about grabbing women’s private parts—were always balanced against a recounting of former president Bill Clinton’s affairs with a White House intern. Trump was clearly unfit for office—but Hillary used a private email server!

This misguided attempt at ‘balance’ likely led to voter confusion. Both candidates were viewed as equally compromised and corrupt. Trump won largely because voters eventually decided there was little difference between the two, so it was better to take a chance on the unknown candidate with no background in politics and a head for business.

Maybe it took four years of political disruption and dysfunction, a pandemic that has claimed more than 230,000 American lives and the worst economic collapse since the Great Depression. But it seems that the mainstream media in the US, which functioned as Trump’s unwitting enablers in 2016, have finally rediscovered their rightful role: to be the country’s gatekeepers against baseless conspiracy theories, to filter out truth from lies, and to hold the powerful accountable for the actions, or their ineptitude.

It’s a lesson well learned.

While China is tightening its coercive campaign against Australia, now targeting the coal industry, its ambassador to the United Nations, Zhang Jun, last week led a protest of 26 nations against economic coercion by the United States.

‘We continue to witness the application of unilateral coercive measures, which are contrary to the purpose and principles of the UN Charter and international law, multilateralism and the basic norms of international relations’, he told the United Nations human rights committee. He spoke on behalf of a group of nations including the major targets of US sanctions: North Korea, Cuba, Venezuela, Iran, Palestine, Russia, Syria and Zimbabwe.

Zhang drew attention to the Non-Aligned Movement’s condemnation of unilateral coercive measures and urged their elimination to support the effectiveness of national responses to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The contradiction of calling out US economic coercion while implementing its own reflects China’s persistent refusal to acknowledge that it ever deploys its economic power over other nations for political purposes.

Even when it launched a concerted campaign against South Korea over its 2017 decision to host a US anti-missile system, China declared before the World Trade Organization that it had done nothing. The campaign, which included a ban on tour groups, a boycott of Hyundai and the forced closure of 70% of the Korean-owned Lotte supermarkets in China, was ultimately relaxed after South Korea negotiated a military deal to ‘normalise’ relations.

As I explain in my new ASPI report, Economic coercion: sanctions and boycotts—preferred weapons of war, released today, both the US and China have intensified their use of economic coercion over the past three years.

The two have radically different methods. The US structure of economic sanctions is highly formalised. A Treasury department, the Office of Foreign Assets Control, maintain lists of sanctioned organisations and individuals running to more than a thousand pages and imposing fearsome penalties for infractions.

China’s system is informal, relying on boycotts and regulatory interventions to deny access to the vast Chinese market. These practices have a long history. The first academic study of Chinese coercion was conducted in 1930, tracing successive boycotts of products from the US, the UK and Japan over the previous 25 years.

By denying that its actions are officially orchestrated, China both escapes accountability and encourages others to second-guess its wishes to avoid becoming a target of its retribution.

Since the Australian government displeased the Chinese government in April this year by calling for an inquiry into the origins of the Covid-19 crisis independent of the World Health Organization, prohibitive tariffs have been placed on Australian barley exports, beef imports from several of the largest Australian processors have been suspended for alleged health infractions, an anti-dumping investigation has been launched into Australian wine, and Chinese government advisories have warned students and tourists against travelling to Australia for safety reasons. Coal industry reports say the order went out last week to Chinese steel mills and ports to halt Australian coal purchases.

While Australia is unlikely to be the target of US sanctions, Australian businesses are at risk of suffering collateral damage. The US asserts extra-territorial power with its sanctions, saying someone may deal with a sanctioned entity or with the United States, but not both.

An Australian company that inadvertently sold goods to Iran, for example, could face prosecution in the US with the risk of heavy fines and a ban on transacting in US dollars. The largest fine for breaching US sanctions was US$8.8 billion imposed on France’s largest bank, PNB Paribas, in 2014.

The Trump administration has seen economic coercion as a much cheaper alternative to military intervention. Ahead of the 2016 election, Donald Trump declared, ‘War and aggression will not be my first instinct.’ Rather, he said, ‘financial leverage and sanctions can be very persuasive—but we need to use them selectively and with total determination’. Trump doubled the rate at which sanctions are imposed, while the level of penalty also increased.

The spread of countries affected by US sanctions has also widened. The US has even imposed economic sanctions on Europe, barring any firm that participates in a gas pipeline from Russia to Germany from any operations in the United States.

The increasing use of economic coercion by China has paralleled its growing economic power. It has been particularly marked this year as China deals both with attempts to allocate responsibility for the Covid-19 pandemic and with the emerging national security concerns in many nations about the risks of Chinese investment. Boycotts and other trade actions have been threatened, and in some cases implemented, against the UK, Germany, Canada, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Sweden and Australia.

Economic coercion has been rising as the institutional underpinning of international trade has become weaker. The WTO has lost its ability to adjudicate disputes, since its appeal panel no longer has a minimum quorum of judges after the US vetoed all appointments. Countries are imposing tariffs, trade quotas and anti-dumping penalties at a much greater rate, often outside WTO guidelines. In the face of rising trade barriers, the G20 has stopped calling on its members to resist protectionism.

It is a global trade environment that makes it easier for countries to use trade as a weapon. As a relatively small country, Australia’s strong interest is in preserving a global trade environment under the governance of the WTO. It will eventually be a loser in a world where trade relations are governed by the exercise of economic power.

While Australia needs to show resolve in the face of Chinese coercion, it should also strive to halt and if possible reverse the erosion of the global trade institutions, by working with allies and regional partners on reform.

John Bolton is opinionated, self-righteous and a notorious hawk. By the time he left his job as US national security adviser, his disagreements with his boss, President Donald Trump, had escalated to the point where they couldn’t even agree on whether he was fired or quit. Under the circumstances, how could his memoir be objective?

However, Bolton spent 17 months at the heart of global decision-making, has an eye for political detail and is legendary for his note-taking. Can anyone interested in knowing what went on in Trump’s Oval Office between April 2018 and September 2019 afford to miss The room where it happened: A White House memoir simply because it is biased?

The book’s greatest strength lies in its detailed inside accounts of events during the author’s tenure. Indeed, Bolton’s revelations proved so sensitive that the Justice Department has launched a criminal investigation to determine whether he illegally disclosed classified information.

During his first months on the job, Bolton accompanied Trump to Singapore, to meet with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un; Brussels, to meet with NATO leaders; London, to meet with Britain’s leaders; and Helsinki, to meet with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Unsurprisingly, it quickly became clear to Bolton that Trump had no international grand strategy and that his thinking was simply an ‘archipelago of dots’.

In Brussels, Trump managed to aggravate the United States’ most important Western allies, demonstrated a lack of understanding of why NATO existed, and kept his aides on tenterhooks about whether he might actually threaten to withdraw from the alliance.

During the summit with Putin, his aides were even more worried. Things went smoothly until the post-summit press conference, when Trump was asked about Russian interference in US elections. To the horror of his aides, he replied that he had received a ‘strong and powerful denial’ from Putin and did not ‘see any reason why it should be’. The White House had to issue a hasty clarification the next day that in fact Trump had meant the opposite.

Perhaps the most interesting chapters relate to the two summit meetings with Kim, where Bolton’s hawkish views differed most sharply from Trump’s. According to Bolton, at the Singapore summit in 2018, Kim skilfully played to Trump’s ego, ‘confessing’ that he had domestic political hurdles to overcome and highlighting the negative impact of the South Korea – US joint military exercises. To Bolton’s frustration, Trump agreed that the exercises were ‘provocative and a waste of time and money’ and gave them up without receiving any concessions in return.

Alerted by this experience, in preparing for the follow-up summit in Hanoi, Bolton carefully briefed a reluctant Trump on when to exercise the ‘walk away’ option. The book provides a fascinating account of the discussions leading to the impasse.

In criticising his adversaries, Bolton pulls no punches. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin ‘never saw a negotiation where he couldn’t make enough concessions to clinch the deal’, the president’s legal adviser Rudy Giuliani was ‘a hand grenade who’s going to blow everybody up’, and the US ambassador to the EU, Gordon Sondland, who irritated Bolton by overstepping his remit to become involved in Ukraine, ‘apparently didn’t have enough to do dealing with the European Union’. Bolton settles scores with Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner and many others, but reserves his sharpest criticism for the president, with an entire chapter on ‘Chaos as a way of life’.

In a few instances, Bolton also shows his loyalty. He devotes only slightly over two pages to the killing by Saudi government operatives of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi, and considers Trump’s bland response ‘in hard-nosed geopolitical terms … the only sensible approach’. The reader searches in vain for any reference to the incident as premeditated murder.

Bolton wears his ideology on his sleeve. Whether being called ‘human scum’ by the North Koreans, or being condemned by Russia or Iran, Bolton says that he feels honoured.

The position of national security adviser is second only to that of secretary of state in the US foreign policy establishment, and has been held by such luminaries as McGeorge Bundy, Zbigniew Brzezinski, Henry Kissinger and Brent Scowcroft. Kissinger held the job for nearly six years, and others for three years or longer. The traditions of the position stand in sharp contrast to Trump’s revolving door, making Bolton the third of four advisers during his tenure to date.

Compared with the outstanding memoirs of several of his predecessors, Bolton’s book is detail-oriented and vindictive. Most significantly, it is devoid of strategic vision. The memoir is a stark reminder of just how much damage Trump has inflicted on the US foreign policy establishment.