Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

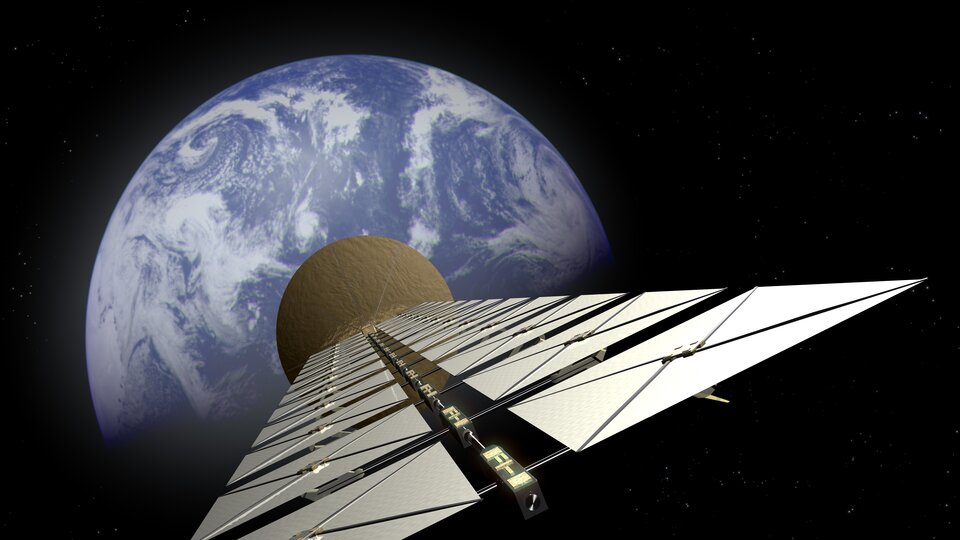

Space-based solar power, or SBSP, refers to orbital systems that collect and harvest solar energy using solar-powered satellites—enormous spacecraft with solar panels. Solar energy is converted into microwaves or lasers and then wirelessly transmitted via high-frequency radio waves to a fixed point on earth throughout the day. Once on the ground, a rectifying antenna, or rectenna, converts the electromagnetic energy into electricity and delivers it to the power grid for energy consumers.

The main benefit of SBSP is its higher energy collection. Because it is unaffected by the weather or time of day, it could provide clean, reliable and efficient energy for satellites and people living in remote communities and in disaster-hit areas worldwide.

The concept of collecting solar power in space isn’t new; however, in recent years, there’s been growing interest in developing SBSP partly due to pressure to meet national and international climate-related goals and achieve national space plans.

While some countries—China, Japan, India, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States—and the European Union are in the race to develop SBSP first, the two leading countries in this competition are China and the US.

In recent decades, China has become increasingly interested in SBSP and appears to be the leader in this area. In 2008, SBSP was listed as a key research program. In March 2016, Zhang Yulin, a national lawmaker and deputy chief of the armament development department of the Central Military Commission, said that China would make use of the space between the earth and the moon for solar power and other industrial-development purposes. He linked SBSP to China’s national goals, declaring, ‘The earth–moon space will be strategically important for the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.’

In February 2019, construction of a ¥200 million ($42 million) testing base commenced at Bishan District in Chongqing, Sichuan. The China Academy for Space Technology’s vice-president, Li Ming, stated that China expects to be the first to build a working solar power station in space with practical value.

Chinese scientists expect to construct small to medium-sized solar power stations to be launched into the stratosphere to produce electricity between now and 2025 and build a megawatt-level power station in 2030.

In June, China announced that it would launch an ambitious space solar power plant program in 2028, two years ahead of the original schedule. At around the same time, researchers from Xidian University successfully tested a 75-metere-high steel structure to divert solar power from outer space.

In the US, although NASA began researching SBSP technologies after the Apollo program (1963–1972), the enormous projected costs meant that the idea wasn’t pursued. Nonetheless, there has been renewed interest in SBSP over the past few decades, including at NASA.

The US Space Force has also expressed interest, and the US Department of Defense is researching SBSP for military purposes.

There is also interest in SBSP at American universities. In 2013, the California Institute of Technology established an SBSP after a donation of more than US$100 million. Last year, the university announced plans to launch a test array by 2023.

It is only a matter of time before SBSP is achieved, potentially creating a new age in clean energy. This could open up opportunities for collaboration as well as assist deep space exploration programs and provide an energy source for moon bases and lunar surface operations. SBSP may become key in what economist Pippa Malmgren calls ‘space-based solutions to earthbound problems’. For instance, the resiliency of SBSP means that it could be used as a backup energy source in the case of power shortages, blackouts or attacks on subnational or national energy infrastructure.

However, developing SBSP is not without technical and non-technical challenges. One of the main barriers is the high cost for things like manufacturing and transportation, and the potential need for significant investment in transmission infrastructure. Other challenges to consider are the efficiency of wireless power transmission, the vulnerability of solar panels to space debris, and the impact on the environment and people. Nonetheless, it is expected that the costs will inevitably decline given the increasing interest from private companies in this area and technological advances.

China appears to be progressing at a faster and more concerted pace. It is already a contender in the global clean energy race and harbours ambitious space plans, and it could become the leading space power if it develops SBSP before the US and the rest of the world. That could result in SBSP becoming an essential element of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, with Beijing offering this form of clean energy to other countries alongside opportunities for greater economic development and connectivity.

In a broader context, the increased interest in developing SBSP may extend the geopolitical domain of competition to geospatial dimensions. The growing rivalry between the US and China on earth has already resulted in competing plans to achieve scientific and economic hegemony in space, including for space-based energy, mining, manufacturing and weapons.

More importantly, perhaps, there’s also the increasing militarisation of space due to competition for military dominance. China’s People’s Liberation Army handles all space planning, and Beijing has already designated space as a military area. China’s 2019 white paper emphasised a growing role in space for the PLA’s Air Force, and a recent report noted that China now has the technology, hardware and knowledge to coordinate a war from space. To further support its space ambitions, China has increased the size of its total operational space fleets by around 70%.

The US–China rivalry further adds to the militarisation of space—China wants to build lunar bases by 2027 and the US by 2025. Based on their existing rivalry, competition between the countries to build bases on planets (such as Mars) is possible. In this context, it’s not unrealistic to imagine that geopolitical and geoeconomic tensions on earth will also be found in outer space or considered an extension of terrestrial activity.

Midterm elections take place in the United States every four years, halfway into a president’s term and two years before the next presidential election. At stake is one-third of the Senate, the entire House of Representatives, some governorships, and many state and local offices.

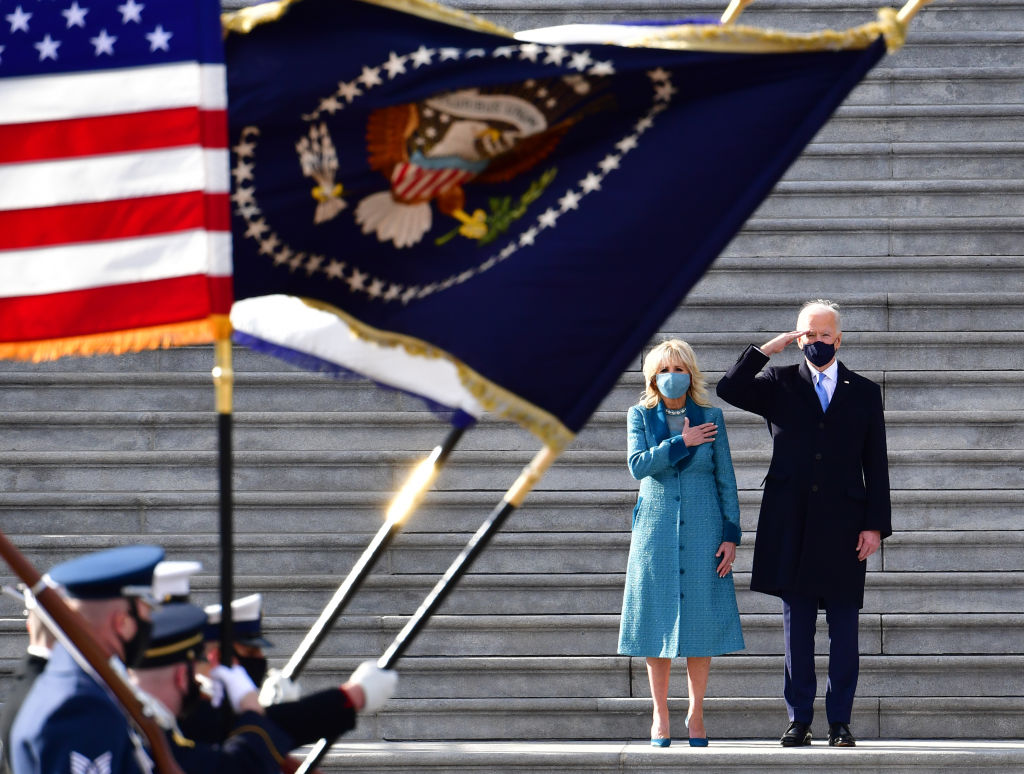

There’s no national vote, but the results tend to reflect where the country stands and are interpreted as a referendum on the party in power (in this case the Democrats, led by President Joe Biden). And while votes are still being counted—and in some cases recounted—it’s not too soon to draw some initial conclusions.

Above all, what was expected to be a decisive no-confidence vote in Biden for the most part failed to materialise. Republicans were widely expected to perform better than they did. The party in power almost always loses seats in midterms, as voters seek to express unhappiness and look for change, and many of the issues at the top of voters’ minds, including inflation, crime and illegal immigration, ought to have resulted in big Republican gains. But voter concerns about other issues, from abortion rights to the health of American democracy, together with questions about the fitness of more than a few Republican candidates, worked in the Democrats’ favour.

As is often the case, foreign-policy concerns seem to have mattered little to voters. Despite the fact that a war is raging in Europe, and that the US is providing the lion’s share of assistance to Ukraine, the reality is that, with few US troops in conflict zones, most voters are preoccupied with domestic matters.

Still, the midterms will have some impact on US foreign policy. The fact that the elections largely took place peacefully and as planned should reassure America’s friends and frustrate those who were hoping that there would be a repeat of the protest and violence that followed the 2020 presidential election. For now, at least, American democracy has held.

Regarding policy, the mixed outcome provides no mandate for significant change. This likely means that economic and military support for Ukraine will continue, although it is possible that there could be some attempts by Congress to limit its scale or link it to some future negotiations. Sanctions against Russia will remain in place.

So, too, will the hardline stance toward China, which reflects a strong political consensus. Indeed, one of Biden’s few bipartisan legislative victories was the CHIPS Act, which provides hundreds of billions of dollars to boost US competitiveness in areas like semiconductor manufacturing. With a divided Congress, one of the few areas for potential agreement will be similar legislation that takes aim at China. For example, the US could introduce a screening process for outbound investment, set new ground rules for Chinese investment in the US, or both.

Support for Taiwan will also continue. The Taiwan Policy Act, which would upgrade bilateral ties in ways sure to provoke China and provide Taiwan with greater military assistance, could be revived by the new Congress. Should Kevin McCarthy become speaker of the House of Representatives, as is quite possible, he will likely travel to Taiwan, which would similarly prompt a strong Chinese response.

Trade is another area in which policy will remain largely unchanged, since there’s little support from either party for new initiatives. The US is unlikely to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership or other trade pacts.

As for Iran, there are disagreements over how to address the nuclear issue. The mounting protests in Iran, however, along with evidence of Iranian military support for Russia, have ended any chance for the US to rejoin the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.

North Korea, with its continued provocations and a seventh nuclear test looming, presents another challenge, but neither US party has a viable alternative policy to put forward. This means that the US will continue to sanction the North.

Support for Israel will continue to receive broad congressional backing. The same cannot be said, however, for initiatives designed to contend with climate change.

More generally, continuity will mostly prevail, partly because the US political system gives the president broad latitude in conducting foreign policy.

The main risk is that a Republican-controlled Senate could block personnel appointments, and a Republican-controlled House could hold hearings on such issues as the Afghanistan withdrawal, which could embarrass and distract the Biden administration.

Perhaps the most important outcome of the midterms is that the results have weakened former president Donald Trump, whereas Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, who easily won re-election, has emerged as a serious contender to lead the Republican Party. While the Democrats exceeded expectations, questions within the party remain as to whether Biden should seek a second term in 2024.

In short, a political earthquake was averted. US foreign policy will remain mostly on familiar terrain for the next two years, until the presidential election. After that, anything can, and possibly will, happen.

The new year is well underway for US President Joe Biden. It’s not pretty. The Russians are coming at Ukraine. The pandemic is not under control; America this year will come close to one million dead from Covid-19. Inflation is at a 40-year high. Biden’s sweeping legislation on social programs and climate change is dying in the Senate. He has been unable to unlock the shackles on voting rights legislation, angering his base of black voters that helped sweep him into the White House. At 42%, Biden’s job approval is the worst of any modern president—save for Donald Trump. The November midterm elections look like a disaster, with the Republicans all but certain to take over the House of Representatives, and perhaps the Senate as well. There’s already talk the House Republicans will impeach Biden in 2023. (Spoiler alert: they will.)

So, what does the president of the United States do? The answer is simple: his job. Get as much done as he is capable of achieving.

In terms of Washington business, the issues are straightforward. Federal funding of the government (‘supply’, in Australian terms) expires on 18 February and must be extended. A deal will be reached.

There’s major legislation to rebuild America’s capabilities in high technology, scientific research and development, and semiconductors. The urgency of meeting what China is projecting across the Indo-Pacific in these fields means that enacting the bill is imperative, and this will get done too.

Discussions will reopen on the stalled Biden ‘Build Back Better’ agenda with the Democratic Senator who has stymied it so far, Joe Manchin of West Virginia. The gulf between the two men is significant. Manchin is a conservative Democrat in a state Trump carried by nearly 70% of the vote. West Virginia is coal, and the heart of Biden’s climate program is renewables.

At stake are Biden’s pledges to ensure that American households have the resources to meet the basic costs of childcare, education, healthcare and care for seniors. Covid exposed the absence of safety and security for tens of millions of Americans when catastrophe strikes. The Biden programs are immensely popular. From the Obama years, Biden and the Democratic leaders in the House and Senate understand that they must find unity and win or be consumed by differences within their ranks and lose. Democrats need to show that in these times they can do big things. They can’t win if they can’t govern. That is what November is all about.

The logic is inescapable, and it’s likely that a more targeted Build Back Better program will be passed. Even if it is ‘only’ a trillion dollars, enactment would mean that Biden will have delivered more than US$4 trillion in economic recovery, Covid response and security for working Americans in his first two years in office. This is on a par with Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Biden also is on the verge of making history with the nomination of a black woman to the Supreme Court. Prospects for confirmation are strong, and a win and will give Biden some added political capital.

Even if this all gets done, Biden’s road to recovery is rocky. Where he stands today is crystal clear: he has lost the confidence of most of the American people. Biden’s Washington is not delivering the goods. Over 70% believe America is headed in the wrong direction. Around 60% believe their households are losing the battle with the cost of living. The lived reality of Covid and inflation obscures the excellent macroeconomic numbers on annual growth, job creation and rising wages.

The penumbra of Trumpism is quite apparent. Some 70% of Americans believe that the country’s political differences are profound, and even more believe that American democracy is endangered.

This is the context for the work of the House Select Committee on the 6 January insurrection. The committee is doing a thorough job of tracking down and interrogating all the principals who had a role in developing and executing that violent assault on America’s democracy. All the former president’s men have been subpoenaed. The committee will soon hold public hearings, which will have the potential, not unlike the Watergate hearings nearly 50 years ago, of educating the American people about what happened and what was at stake. If dramatic enough, the hearings could shake the political landscape.

What will Biden face from the Republicans this year? Theirs is a simple playbook: don’t do anything to distract from a man besieged. Push buttons on the fears afflicting Republican and especially independent voters. Inflation is out of control and is killing your pocketbook. You trusted that Biden would make America Covid-normal, but it’s not, affecting your family and your job. The woke left is controlling our schools and our kids’ minds. Crime is skyrocketing and Biden wants to take away your guns. The borders are out of control and dangerous immigrants are flooding in. The left is dictating Biden’s agenda, and that agenda is socialism. And forget about voting rights.

Biden’s polling started heading south last September when the surge of the Delta variant coincided with the horrific exit from Afghanistan. That tested perceptions of Biden’s expertise in managing foreign policy—a significant selling point for his presidency. This is why the outcome of the Russia–Ukraine situation, beyond the issue of security in Europe, is so important for Biden. If he can stare down Russian President Vladimir Putin, with Ukraine saved, it will be a significant victory—not necessarily like John F. Kennedy and the Cuban missile crisis, but not dissimilar. If Russia takes Ukraine, Biden will be vilified as the president who ‘lost’ that country. It will be quite searing.

And who knows what nasty surprises are coming from Iran and North Korea?

We can take the measure of this president when he delivers the State of the Union address on 1 March. He will say that the state of the union is strong, and that there’s nothing America and Americans can’t do if they are together. He will believe every word he will utter. But will the American people?

The United States and China are competing for dominance in technology. America has long been at the forefront in developing the technologies (bio, nano, information) that are central to economic growth in the 21st century and US research universities dominate higher education globally. In Shanghai Jiao Tong University’s annual Academic Ranking of World Universities, 16 of the top 20 institutions are in the US; none is in China.

But China is investing heavily in research and development, and it is already competing with the US in key fields, not least artificial intelligence, where it aims to be the global leader by 2030. Some experts believe that China is well placed to achieve that goal, owing to its enormous data resources, a lack of privacy restraints on how that data is used, and the fact that advances in machine learning will require trained engineers more than cutting-edge scientists. Given the importance of machine learning as a general-purpose technology that affects many other domains, China’s gains in AI are of particular significance.

Chinese technological progress is no longer based solely on imitation. Former US president Donald Trump’s administration punished China for its cybertheft of intellectual property, coerced IP transfers and unfair trade practices. Insisting on reciprocity, the US argued that if China could ban Google and Facebook from its market for security reasons, the US can take similar steps against Chinese giants like Huawei and ZTE. But China is still innovating.

After the 2008 global financial crisis and the ensuing great recession, Chinese leaders increasingly came to believe that America was in decline. Abandoning Deng Xiaoping’s moderate policy of keeping a low profile and biding one’s time, China adopted a more assertive approach that included building (and militarising) artificial islands in the South China Sea, economic coercion against Australia and the abrogation of its guarantees with respect to Hong Kong. In response, some people in the US began to talk about the need for a general ‘decoupling’. But as important as it is to unwind technology supply chains that directly relate to national security, it is a mistake to think that the US can decouple its economy completely from China without incurring enormous costs.

That deep economic interdependence is what makes the US relationship with China different from its relationship with the Soviet Union during the Cold War. With the Soviets, the US was playing a one-dimensional chess game in which the two sides were highly interdependent in the military sphere but not in economic or transnational relations.

With China, by contrast, the US is playing three-dimensional chess with vastly different distributions of power at the military, economic and transnational levels. If we ignore the power relations on the economic or transnational boards, not to mention the vertical interactions between the boards, we will suffer. A good China strategy therefore must avoid military determinism and encompass all three dimensions of interdependence.

The rules governing economic relations will need to be revised. Well before the Covid-19 pandemic, China’s hybrid state capitalism followed a mercantilist model that distorted the functioning of the World Trade Organization and contributed to the rise of disruptive populism in Western democracies.

Today, America’s allies are far more cognisant of the security and political risks entailed in China’s espionage, coerced technology transfers, strategic commercial interactions and asymmetric agreements. The result will be more decoupling of technology supply chains, particularly where national security is at stake. Negotiating new trade rules can help prevent that decoupling from escalating. Against this backdrop, middle powers could come together to create a trade agreement for information and communication technology that would be open to countries meeting basic democratic standards.

One size will not fit all. In areas like nuclear non-proliferation, peacekeeping, public health and climate change, the US can find common institutional ground with China. But in other areas, it makes more sense to set our own democratic standards. The door can remain open to China in the long run, but we should accept that the run could be very long indeed.

Notwithstanding China’s growing strength and influence, working with like-minded partners would improve the odds that liberal norms prevail in the trade and technology domains. Establishing a stronger transatlantic consensus on global governance is important. But only by cooperating with Japan, South Korea and other Asian economies can the West shape global trade and investment rules and standards for technology, thereby ensuring a more level playing field for companies operating abroad.

Taken together, democratic countries’ economies will exceed China’s well into this century, but only if they pull together. That diplomatic factor will be more important than the question of China’s technological development. In assessing the future of the US–China power balance, technology matters, but alliances matter even more.

Finally, a successful US response to China’s technological challenge will depend upon improvements at home as much as on external actions. Increased support for research and development is important. Complacency is always a danger, but so, too, is lack of confidence or an overreaction driven by exaggerated fears. As former Massachusetts Institute of Technology provost John Deutch contends, if the US attains its potential improvements in innovation, ‘China’s great leap forward will likely at best be a few steps toward closing the innovation leadership gap that the United States currently enjoys.’

Immigration also will play an important role in maintaining America’s technology lead. In 2015, when I asked former Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew why he did not think China would surpass the US, he pointed to America’s ability to draw upon the talents of the whole world—a possibility that is barred by China’s ethnic Han nationalism. It is no accident that many Silicon Valley companies have Asian founders or CEOs.

With enough time and travel, technology inevitably spreads. If the US lets its fears about tech leakage shut it off from such valuable human imports, it will surrender one of its biggest advantages. An overly restrictive immigration policy could severely curtail technological innovation—a fact that must not get lost in the heated politics of strategic competition.

The terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 on the United States were a horrific shock. Images of trapped victims leaping from the Twin Towers are indelible, and the intrusive security measures introduced in the wake of the attacks have long since become a fact of life.

But sceptics doubt that it marked a turning point in history. They note that the immediate physical damage was far from fatal to American power. It is estimated that the United States’ GDP growth dropped by three percentage points in 2001, and insurance claims for damages eventually totalled over US$40 billion—a small fraction of what was then a US$10 trillion economy. And the nearly 3,000 people killed in New York, Pennsylvania and Washington DC when the al-Qaeda hijackers turned four aircraft into cruise missiles was a small fraction of US travel fatalities that year.

While accepting these facts, my guess is that future historians will regard 9/11 as a date as important as the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. The surprise attack on the US naval base in Hawaii killed some 2,400 American military personnel and destroyed or damaged 19 naval craft, including eight battleships. In both cases, however, the main effect was on public psychology.

For years, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had tried to alert Americans to the Axis threat but had failed to overcome isolationism. All that changed with Pearl Harbor. In the 2000 presidential election, George W. Bush advocated a humble foreign policy and warned against the temptations of nation-building. After the shock of 9/11, he declared a ‘global war on terror’ and invaded both Afghanistan and Iraq. Given the proclivities of top members of his administration, some say a clash with Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was predictable in any case, but not its manner or cost.

What 9/11 illustrates is that terrorism is about psychology, not damage. Terrorism is like theatre. With their powerful military, Americans believe that ‘shock and awe’ comes from massive bombardment. For terrorists, shock and awe comes from the drama more than the number of deaths caused by their attacks. Poisons might kill more people, but explosions get the visuals. The constant replay of the falling Twin Towers on the world’s television sets was Osama bin Laden’s coup.

Terrorism can also be compared to jujitsu, in which a weak adversary turns the power of a larger player against itself. While the 9/11 attacks killed several thousand Americans, the ‘endless wars’ that the US subsequently launched killed many more. Indeed, the damage done by al-Qaeda pales in comparison to the damage America did to itself.

By some estimates, nearly 15,000 US military personnel and contractors were killed in the wars that followed 9/11, and the economic cost exceeded US$6 trillion. Add to that the number of foreign civilians killed and refugees created, and the costs grow even more enormous. The opportunity costs were also large. When President Barack Obama tried to pivot to Asia—the fastest-growing part of the world economy—the legacy of the global war on terror kept the US mired in the Middle East.

Despite these costs, some say that the US achieved its goal: there hasn’t been another major terrorist attack on the US homeland on the scale of 9/11. Bin Laden and many of his top lieutenants were killed, and Saddam Hussein was removed (though his connection to 9/11 was always dubious). Alternatively, a case can be made that bin Laden succeeded, particularly if we consider that his beliefs included the value of religious martyrdom. The jihadist movement is fragmented, but it has spread to more countries, and the Taliban have returned to power in Afghanistan—ironically, just before the 9/11 anniversary that President Joe Biden originally set as the target date for withdrawing US troops.

It’s too early to assess the long-term effects of the US withdrawal from Afghanistan. The short-term effects of the chaotic exit are costly, but in the long term, Biden may come to be seen as correct to have forsworn the effort at nation-building in a country divided by mountains and tribes and united mainly by opposition to foreigners.

Leaving Afghanistan will allow Biden to focus on his grand strategy of balancing the rise of China. For all the damage done to US soft power by the chaotic manner of the exit from Afghanistan, Asia has its own longstanding balance of power in which countries like Japan, India and Vietnam don’t wish to be dominated by China and welcome an American presence. When one considers that within 20 years of America’s traumatic exit from Vietnam, the US was welcome in that country as well as the region, Biden’s overall strategy makes sense.

At the same time, 20 years after 9/11, the problem of terrorism remains, and terrorists may feel emboldened to try again. If so, the task for US leaders is to develop an effective counterterrorism strategy. Its core must be to avoid falling into the terrorists’ trap by doing great damage to ourselves. Leaders must plan to manage the psychological shocks at home and abroad.

Imagine what the world would be like if Bush had avoided the tempting rallying cry of a global war on terror and responded to 9/11 by carefully selected military strikes combined with good intelligence and diplomacy. Or, if he had gone into Afghanistan, imagine that he had withdrawn after six months, even if that had involved negotiating with the despised Taliban.

Looking forward, when the next terrorist attacks come, will presidents be able to channel public demand for revenge by precise targeting, explaining the trap that terrorists set, and focusing on creating resilience in US responses? That is the question Americans should be asking, and that their leaders should be addressing.

The Biden administration’s 100-day review of supply-chain vulnerabilities has produced fresh insights into the United States’ dependence on China for supplies of rare earths and other critical materials but falls far short of a strategy to achieve any change.

The review, led by the Department of Defense, expresses confidence that military needs for critical minerals could be met in a crisis by diverting supplies from civilian use, but says this would result in ‘very large essential civilian shortfalls’ that would be more than 10 times the peacetime needs of defence.

‘Even though the US Armed Forces have vital requirements for strategic and critical materials, the essential civilian sector would likely bear the preponderance of harm from a disruption event,’ the report says.

The review of critical minerals supplies is included in a four-part study also covering semi-conductors, pharmaceutical ingredients and large-scale batteries, which President Joe Biden ordered shortly after assuming office and released last week.

The most immediate outcome of the review is a statement by the White House that it is considering a further review into rare-earth permanent magnets, to establish whether dependence on China for their supply represents a threat to national security that would warrant the imposition of tariffs.

The use of national security to impose tariffs was pioneered by the Trump administration, which used the exemption from World Trade Organization rules to impose them on US steel and aluminium imports, and threatened to use them to impede imports of motor vehicles.

The idea is that if the tariffs were set high enough, they would stimulate some domestic US production of rare-earth magnets; however, they would also raise costs for end users making motors for electric cars, wind turbines, computer hard-drives and missile guidance systems.

They would likely encourage a trend exposed by the new analysis for US firms to import components containing rare-earth magnets, rather than manufacture the components themselves. The study found that 60% of essential civilian demand for rare-earth magnets was embedded in other imported manufactured goods.

‘Implicit in this trade phenomenon is the gradual decline in value-creation, innovation, research, and human capital development,’ the report says.

By contrast, two-thirds of defence demand is for direct rare-earth permanent magnets, which are then used by US manufacturers.

‘DoD’s import posture affords it marginally greater visibility into its foreign reliance compared to other essential civilian sectors, who may not even realize their exposure to an NdFeB [rare earth] magnet disruption since it is several tiers removed from the products they purchase from foreign sources,’ the report says.

The study has identified which industries are using rare-earth elements, either purchased directly or ‘embedded’ in other inputs. It estimates that the US private sector uses rare earths worth US$613 million as essential inputs to total manufacturing activity worth US$496 billion.

For example, spending on rare-earth magnets by manufacturers of computer storage devices is $US78 million; medical and therapeutic devices, US$39 million; air and gas compressors, US$24 million; and phones, $38 million.

Magnets are by far the largest use of rare-earth minerals by value globally. Other major uses for rare earths include as catalysts for oil refining and petrochemicals, pigments for dyes and paints, pure glass for optical instruments, ceramics for turbines, and electronic components and phosphors for lighting and screens.

The review emphasises the technical difficulty involved in the rare-earth industry. ‘As a series of complex extraction, chemical, and refining operations, establishing strategic and critical material production is an extremely lengthy process. Independent of permitting activities, a reasonable industry benchmark for the development of a mineral-based strategic and critical materials project is not less than ten years.’

It notes that at the peak of market interest in the rare-earth industry in 2011, there were approximately 275 rare-earth projects under development in 30 countries, excluding those in China, Russia and India. Only two projects have come to full production—Australia’s Lynas and the US’s Mountain Pass, with the latter partly Chinese owned and sending its output to China for processing.

‘[I]t is quite common for most companies to fail to reach the end of this development process, simply due to the long project development time without cash flows to offset expenses and the technical challenges associated with large, complex project financing for materials production.’

However, the study attributes the erosion of US capacity to the doctrine of economic efficiency, which it contrasts with the single-minded focus of the state-driven strategy of China.

‘Economic efficiency took priority over diversity and sustainability of supply—made manifest in the slow erosion of manufacturing capabilities throughout the United States and many other nations. In addition, as the point of consumption drifted farther and farther from the point of production, U.S. manufacturers increasingly lost visibility into the risk accumulating in their supply chains. Their suppliers of strategic and critical materials, and even the workforce skills necessary to produce and process those materials into value-added goods, became increasingly concentrated offshore. In such opaque conditions, the exploitation of forced labour and a disregard for environmental emissions and workforce health and safety could thrive.’

‘By contrast, the Chinese Government has focused on capturing discrete strategic and critical material markets as a matter of state policy. For example, China implemented a value-added tax (VAT) rebate for rare earth exports in 1985, which contributed to the erosion and then elimination of US production in the global market.’

‘China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology took the lead in forcing the vertical and horizontal integration of Chinese rare earth companies—pushing privately-held rare earth miners out of the market in favor of a handful of national champions. This central planning and active management of the rare earth industrial base continues, with new draft management regulations under review and even more expansion projects underway.’

The review’s recommendations will do little to close the gap in the US capability. Surprisingly, the top priority is to develop new sustainability standards for the extraction and processing of critical materials, suggesting that legislated standards will be an incentive to investment in the US.

It also recommends greater attention to environmentally sensitive recycling, although the analysis acknowledges that recycling can never overcome the gap. It is often difficult to extract the rare earths from the components, such as computer hard drives, that contain them.

The most concrete recommendation is greater use of the Defense Production Act, which empowers the government to advance loans to help finance critical mineral developments, though there’s no guidance for how this should be done.

The Trump administration used this legislation to finance the production of personal protective equipment and vaccines in the fight against Covid-19. However, the funds were disbursed in a scatter-gun manner, and many of the loans went to military projects with no relevance to the pandemic.

The US has a lot to learn from the Chinese when it comes to central planning.

President Joe Biden’s statement this week of an ‘investigation into the origins of Covid-19’ shows that the US intelligence community is making progress towards uncovering whether the virus was released because of a ‘laboratory accident’ or ‘from human contact with an infected animal’.

Biden tells us his intelligence agencies agree these are the ‘two likely scenarios’ with one agency leaning to the lab accident and two towards the pangolin-bites-man theory, while the others ‘do not believe there is sufficient information to assess one to be more likely than the other’.

It’s no small thing to get all 18 American intelligence agencies agreeing that the laboratory accident scenario was a likely cause of the pandemic. The agencies have clearly made progress since the first ‘intelligence community statement on origins of Covid-19’, released in April 2020, which found that the virus ‘was not manmade or genetically modified’ but could do no more than promise to ‘rigorously examine emerging information’ about the origins of Covid-19.

Biden has given his intelligence system 90 days to ‘bring us closer to a definitive conclusion’. I’ll speculate here that the administration thinks a conclusion can made. Why set up the intelligence agencies to fail?

The president also said that the further inquiry would include asking ‘specific questions for China’. It is astonishing that it has taken 15 months before a US administration decided to put Beijing on the spot with some direct questions. In effect Xi Jinping is on 90 days’ notice for his regime to put aside the bluster and make its own case about the ‘two likely scenarios’.

I’m with the courageous US intelligence agency that is leaning to the ‘laboratory accident scenario’. Here’s why.

First, we know that China has long had an interest in developing biological and chemical weapons. The US State Department made that assessment public years ago.

Second, we know that Chinese military personal and scientists have written studies on how to fight wars with biological agents. The Australian’s Sharri Markson has reported extensively on this. It’s true that there is a huge volume of Chinese military writing which does not necessarily represent communist party ‘policy’, but it’s significant that specialists inside Chinese military science are writing on this subject.

Third, we know that the Wuhan Institute of Virology is designed to be a very secure research facility and prior to 2019 was working on coronaviruses, including on so-called ‘gain of function’ research about how to make a virus more virulent.

The much-discredited joint World Health Organization–China study into the origin of the pandemic said that the strain of coronavirus closest in genetic makeup (in fact 96.2% identical) to the virus that causes Covid-19 was ‘detected in bat anal swabs [that] have been sequenced at the Wuhan Institute of Virology’.

Fourth, we know that serious concerns existed about security at the WIV. In late 2017, the US embassy in Beijing flagged these worries in a cable reporting there was ‘a serious shortage of appropriately trained technicians and investigators needed to safely operate this high-containment laboratory’. The embassy was so worried that it wanted Washington to help China improve the laboratory’s biosecurity. The proposal was never acted on.

Fifth, we know that the WIV was presenting itself as a civilian institution, but a US intelligence judgement reported by then secretary of state Mike Pompeo in January 2021 was that ‘the WIV has engaged in classified research, including laboratory animal experiments, on behalf of the Chinese military since at least 2017.’

Sixth, a point highlighted in the WHO–China study, the WIV-linked Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention laboratory moved on 2 December 2019 to a new location near the Huanan wet market. The study dryly states ‘such moves can be disruptive for the operations of any laboratory.’

The seventh point is that it seems at least three workers at the WIV fell ill with Covid-19-like symptoms some time before the first publicly known cases emerged in December 2019. This was mentioned by Pompeo in January and is now being bolstered, according to the New York Times, with corroborating information from non-US sources.

Finally, there is the remarkable Chinese Communist Party cover-up of the whole issue: The fatuous claims that Covid-19 was planted by US military personnel visiting Wuhan or arrived on frozen salmon; the refusal to hand over actual samples of the original virus as opposed to its genomic sequence; the refusal to grant access to the WIV until the tightly stage-managed WHO–China study visit on 3 February 2021; the over-the-top attempts to prevent international access to research the virus; and the hysterical denunciation of Australia’s request for a credible international examination.

It’s almost as though Xi has something to hide.

Put these elements together and it becomes clear that China was working on coronaviruses, was interested in biological weapons, had thought about how to fight with them and had sufficiently shoddy processes to make the ‘laboratory accident scenario’ a real possibility.

Something else we should be clear about is that once the virus was released, the CCP instantly weaponised its use. It allowed international flights out of Wuhan for weeks while countries dithered about closing borders.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi told his Australian counterpart Marise Payne on 30 January last year that ‘given the current situation, the epidemic is generally preventable, controllable, and curable’. This was at precisely the time China was stripping stocks of medical equipment and protective gear from Australia and other democracies.

Again, to speculate: I suspect Biden has a clear sense of what his intelligence review will find. We are getting closer to uncovering the reality of what happened in Wuhan. The truth could force a rethink about how the democratic world deals with China and, domestically, lay a major blow on Xi’s legitimacy as the people’s hero in the struggle against Covid-19.

In 2034, a small American flotilla on a routine ‘freedom of navigation’ patrol in the South China Sea encounters an unflagged trawler in distress, with smoke billowing from its bridge. What follows is far from routine, as events escalate and then spin out of control. That’s the beginning of 2034: A novel of the next world war.

This isn’t your average airport bookstore blockbuster. Novelist Elliot Ackerman, the author of several award-winning military-themed novels, including Waiting for Eden, has teamed up with James Stavridis, who spent more than 30 years in the US Navy, including long operational stints in the Indo-Pacific, rising to the rank of four-star admiral. He also served as supreme allied commander in NATO and dean of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University in Massachusetts. Stavridis has published widely on naval affairs, including Sea power: The history and geopolitics of the world’s oceans, and contributes actively to the ongoing international discussion on the implications of China’s rise.

Stavridis and Ackerman have combined their talents—the former’s detailed operational knowledge of military strategy and tactics and the latter’s narrative skills—to come up with a realistic, detailed and highly readable account of how the next world war might begin.

The book is built around a scenario in which China, once it has brought its military up to world-class standards (it is currently aiming for 2035), moves quickly to oust the United States and other foreign navies from the South China Sea and use its new-found power to unite Taiwan with the mainland. It works closely with its allies, Iran and Russia, to achieve that.

China’s advanced offensive cyber capabilities catch the US off guard, highlighting its Achilles heel—the book devotes an entire chapter to ‘blinding the elephant’, and it’s a comprehensive attack. China’s technological edge allows it to black out US military communications in the South China Sea, have its Iranian allies remotely take control of a US fighter plane to land it at an Iranian airfield and take the pilot hostage, use cyber cloaking, stealth materials and satellite spoofing to keep its fleet virtually invisible for extended periods, hack into secure White House communications systems and engineer a blackout of Washington. Using more conventional military means, China’s Russian allies blow up underwater cables in the Barents Sea, drastically slowing internet connectivity across the US.

The book realistically describes strengths and weaknesses on both sides. China has superior cyber technology but is operationally inexperienced and bureaucratic, especially when faced with the unexpected. The US, on the other hand, is remarkably ill-prepared for China’s cyber onslaught but superior in terms of operational experience and flexibility.

The authors present a chilling scenario of the two antagonists escalating the conflict through a series of miscalculations and mistakes. The US initially underestimates China’s technological capabilities and falls into a relatively simple trap baited with a Chinese fishing boat. When the US predictably mobilises a large naval force, China’s response is excessive. Unaware of the US ‘red lines’, the Chinese unintentionally provoke a tactical nuclear strike on a Chinese port. A Chinese tactical counterstrike follows, and the book describes the simplistic thinking that could lead to an escalation of tit-for-tat responses.

The book’s publication is particularly timely, given the recent warning by outgoing Admiral Phil Davidson, who led US operations in the Indo-Pacific, that China could attempt to take over Taiwan as early as 2027. In testimony to the US Congress in March, Davidson said ‘I cannot for the life of me understand some of the capabilities that [China is] putting in the field, unless … it is an aggressive posture’.

Not surprisingly, given Stavridis’ background, the book has a strong military bent. The authors play up the role of the military chain of command as the crisis escalates and pay less attention to political leaders and the behind-the-scenes diplomatic negotiations that one would expect in a crisis of this magnitude.

The Chinese Communist Party general secretary and president generally also chairs the Central Military Commission and would play a key role in crisis decision-making, but is not mentioned. On the US side, the political leadership is presented as being surprisingly reticent to act. The reader waits in vain for either leader to activate the hot line. But that may accurately reflect the current lack of effective communication mechanisms between the US and China.

2034 is thought-provoking reading for military and diplomatic professionals dealing with China, and for the generalist concerned with China’s rise. The scenario outlined by Stavridis and Ackerman lends credence to recent calls for the US to strengthen its military capabilities in the Indo-Pacific. It’s also a riveting read.

US President Joe Biden has sent Congress his requested budget for the 2022 fiscal year. Due to the timelines of a presidential transition year, there’s not a lot of detail yet, but there’s enough to answer one big question in the strategic policy sphere: there won’t be a big change to the defence budget.

The document’s preamble states that ‘America is confronting four compounding crises of unprecedented scope and scale all at the same time.’ For those of us in the national security community, it’s a useful reminder of Biden’s priorities that China’s increasing power and aggression is not one of the four; rather, they are the pandemic, the resulting economic crisis, a ‘national reckoning on racial inequality centuries in the making’, and climate change. Competition with China is mentioned, but Biden makes clear that it isn’t simply or even mainly a military problem. Instead, he seeks to outcompete China through ‘a comprehensive strategy to reimagine and rebuild a new American economy’.

On top of that, Biden wasn’t exactly dealt a great hand in terms of cash in the bank. The budget request is only for discretionary funding. The bulk of the US federal budget is mandated or non-discretionary funding, which includes things like Social Security (retirement and disability benefits) and Medicare (health care for seniors). Over the past 35 years, mandated expenditure has grown from rough parity with discretionary funding to more than twice as much. In 2020 it blew out even further, to around three times as much, because of unemployment benefits and other support payments made during the pandemic (discretionary spending was around US$1.6 trillion and mandated was nearly US$4.9 trillion). With that, the annual deficit, which had been approaching US$1 trillion, surged past US$3 trillion. That also brought the public debt to US$21 trillion, or around 100% of GDP.

Within the discretionary budget, there’s been a rough 50–50 split between defence and non-defence spending. With most of the federal budget essentially untouchable, it might have been tempting for Biden to take the razor to defence spending to find the discretionary funds to support his domestic priorities. But he hasn’t done that. His discretionary budget request maintains an almost even split between defence and non-defence spending, despite his intent to reverse the long-term trend of declining non-defence discretionary spending.

The total defence request is US$753 billion, around US$12 billion more than President Donald Trump’s 2021 budget. Of that, US$715 billion is for the Department of Defense itself. In comparison, the rest of the discretionary budget, which funds everything else from energy to education, is only slightly more at US$769 billion. Defence spending is around 3.2% of GDP—far more than America’s allies, including Australia.

It’s a budget that probably disappoints the doves who want significant readjustment of spending priorities, and it’s about as good as the hawks could have reasonably hoped for.

The request acknowledges that more detail is to come. Even so, the lack of specifics around the Department of Defense stands out. While other departments’ individual programs are described with dollars attached, the DoD has only high-level language with no dollars. Whether that’s because issues such as health, energy and the environment are higher priorities, or because the administration hasn’t yet been able get its arms around the elephantine problems facing the DoD is not clear. But the discrepancy between the boilerplate language on defence and the sense of urgency and renewal in other areas is striking.

What is there on defence largely gives an impression of continuity. Countering the threat from China remains the department’s top challenge. There’s a commitment to ‘a strong, credible nuclear deterrent for the security of the Nation and US allies’. The recapitalisation of the ballistic missile submarine fleet—the US Navy’s most expensive program—will continue.

The Biden administration’s conviction that the means to manage competition with China are not purely military ones is evident in the document’s emphasis on rebuilding the economy and working with partners and allies. Importantly, the request includes a substantial increase to the State Department budget. But the need to deliver military capability is also real.

The administration seeks to ‘reimagine’ the economy, and elsewhere Biden has proposed bold ideas that affect all departments, such as putting climate change into their core planning. But there are few clear signs in this document of imagination at work in the administration’s plans specifically for defence. However, doing business the same way is unlikely to enable the US to counter the threats it perceives around the world.

The army, navy and air force all face major recapitalisation challenges, with fleets ageing out and the mounting cost of replacements simply unaffordable. Meanwhile, Chinese military power grows apace, reflecting its role as the world’s factory. China’s shipyards are pumping out ships at a rate the US can’t match. Trump’s defence secretary grappled for a year with the problem of how to design a navy that could counter China before delivering a plan that was essentially unaffordable and unachievable.

Biden’s administration will have to wrestle with the same challenges, and the lack of detail in the budget request suggests it hasn’t resolved where, or indeed whether, it will make fundamental changes. The boilerplate language leaves some room for manoeuvring. For example, it doesn’t sign up to a target for the size of the fleet, such as the 355 ships that have been an unattainable and arguably distracting goal for years. There are references to innovation and emerging technologies, such as ‘remotely operated and autonomous systems’ and hypersonics.

The request also refers to divesting ‘legacy capacity and force structure’. Again, this is standard boilerplate, but potentially offers cover for some large force structure decisions, such as reducing the size of the army to reinvest in the maritime and air assets needed in the Pacific.

Biden’s decision to follow through on the withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan suggests that he’s willing to make tough calls. One may not agree with the decision, but he broke with the status quo, even if the outcome is not clear. That decision will likely play well to a US public tired of ‘endless wars’, but it won’t by itself make much difference to the balance of power in the western Pacific. That will likely require a combination of more tough decisions and greater imagination than was revealed in this budget request.

On 26 February, the Paris-based Financial Action Task Force (FATF), a 39-country anti–money laundering and counter–terrorism financing watchdog, decided to yet again keep Pakistan on the ‘grey list’ for failing to complete the last three actions it had to take to be removed from the list.

This decision will have repercussions on US–Pakistan relations.

While the FATF president, Marcus Pleyer, noted that, since the last FATF meeting in October, Islamabad had made ‘significant progress’ in addressing the last three of the 27 action items assigned to it in June 2018, he stressed that there remained ‘serious deficiencies in mechanisms to plug terrorism financing’.

Pakistan is no doubt disappointed. Its foreign minister, Shah Mehmood Qureshi, appeared optimistic about the outcome of the meeting given that Pakistan had indeed taken some significant steps. In the past few months, the Pakistan authorities had arrested two top leaders of Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), the banned Kashmir-focused terrorist group that had been blamed by the US and India for the 2008 Mumbai attack in which more than 160 people were killed. Zakiur Rehman Lakhvi, LeT supreme commander, was given a five-year jail sentence for terror financing in January 2021 and Hafiz Saeed, the founder of the LeT, received a 10-year prison sentence in November 2020. Still, even with the arrest of these high-value terrorists, it’s unlikely that privately the government of Pakistan seriously thought it would be taken off the list.

According to Pleyer, Pakistan ‘must improve its investigations and prosecutions of all groups and entities financing terrorists … and show that penalties by courts are effective’. Once it has met these requirements, the FATF will reassess Pakistan’s eligibility to be taken off the grey list at its next meeting, in June.

The reason Pakistan is so keen to get a clean bill of health from the FATF is that being on the grey list limits Islamabad’s ability to access foreign funds to assist with its developmental and budgetary needs. It has been estimated by Tabadlab, an Islamabad-based think tank, that the listing has led to reduced household and government consumption, exports and direct foreign investment amounting to about US$38 billion.

Another direct consequence of being on the grey list since 2018 is that Pakistan has had to rely on the International Monetary Fund, Saudi Arabia and China to regularly bail it out financially. Pakistan simply cannot make ends meet on its own. However, by having to increasingly turn to China for its economic survival, in addition to the massive economic costs of the US$64 billion, 30-year China–Pakistan Economic Corridor project, Pakistan has reached a level of economic dependence on Beijing that is becoming irreversible.

However, China hasn’t bailed Pakistan out because of kindness. On the contrary, throwing a lifeline on a regular basis ensures that this nuclear-armed neighbour, with a population of over 220 million, doesn’t collapse economically. It is pure self-interest. But even more important, as part of the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, the development of the port of Gwadar on the Indian Ocean, along with roads and other infrastructure that link Pakistan with the western province of Xinjiang, means that China effectively becomes a two-ocean state. Put differently, Pakistan is absolutely a force multiplier for China and therefore a Chinese asset worth safeguarding.

Pakistan’s now being solidly in Beijing’s strategic and economic orbits not only complicates Washington’s ability to manoeuvre in that critical geostrategic region, but also puts additional stress on the bilateral relationship at a time when President Joe Biden and his administration are trying to manage an honourable exit from neighbouring Afghanistan.

Washington recognises the important role Islamabad played in getting the Taliban to sign up to the February 2020 peace deal and the role it continues to have in the now deeply troubled Afghan peace process. This was reaffirmed by the new secretary of defence, Lloyd Austin. However, if Biden decides not to withdraw the remaining 2,500 military personnel from Afghanistan by 1 May, as the US is meant to according to the peace agreement, the impact on US–Pakistan relations will be very serious. Once again, Islamabad will feel let down by the Americans. However, despite that, Washington is unlikely to resume military aid to Pakistan of around US$1 billion annually which was suspended by President Donald Trump in 2018.

But an even greater stress point for US–Pakistan relations is America’s ever-deepening relations––military and economic––with India, Pakistan’s nemesis since partition in 1947. Austin reaffirmed that under his watch he would seek to ‘further operationalise India’s “major defence partner” status and continue to build upon existing strong defence cooperation’. Not surprisingly, this will inevitably push Pakistan even deeper into China’s orbit.

While Biden may have been interested in making a new, clean start of sorts with Islamabad, he is no longer in the mood for that following the Pakistan supreme court’s recent decision to uphold a lower provincial court’s ruling to release Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, who had been acquitted of any involvement in the beheading of Daniel Pearl, a Wall Street Journal reporter, in 2002. This has seriously upset the Biden administration.

So, what does Pakistan need to do to regain America’s trust on the counterterrorism front? Despite the Pakistan government’s arrest of several high-profile terrorist leaders, however, there’s a nagging perception––justified or not––that the country remains a nest of terrorists supported in some cases by the military. It’s critical for Islamabad to dispel this perception. To start with, it needs to arrest some of the remaining terrorist leaders, in particular Masood Azhar, the leader of the banned, Kashmir-focused Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM), and other fellow ideological followers. There are indications that the Pakistan government is indeed considering taking action against the JeM.

If Islamabad did arrest and hand down long prison sentences to some of the remaining terrorist leaders, it would certainly help put the US–Pakistan relationship on a stronger footing and give a real boost to Pakistan’s chances of finally being taken off the grey list when the FATF meets again in a few months. Not to do so would be a very serious mistake indeed.