Why encouraging US allies in Asia to proliferate isn’t a good idea

In a recent commentary in The National Interest, titled ‘Let Asia go nuclear’, Harvey Sapolsky and Christine Leah outlined a case in favour of the US accepting nuclear proliferation by its allies in the Asia Pacific. The core of their position is that the allies have opted for US nuclear assurances and conventional protection because those are cheaper than constructing their own nuclear arsenals. They suggest that ‘tailored proliferation’ by US allies would ease US burdens and simultaneously allow the states in question to enjoy clearer protection from their own indigenous nuclear arsenals than they do under the existing ‘extended deterrence’ arrangements. And they believe such proliferation wouldn’t be destabilising, because US allies are responsible stakeholders in the regional and global order, and none would be in any hurry to lob a nuclear weapon at anyone else.

Let’s put aside the assertion that the allies chose extended nuclear assurance because it was cheaper—though I don’t believe that was the primary motive for any of the countries. And let’s assume there’s a domestic consensus in each of the allied states to move down the nuclear path—an assumption that might be a bridge too far in the case of South Korea, is a bridge too far in the case of Japan, and several bridges too far in the case of Australia and others. I’m more interested in what happens afterwards—when, say, Japan, South Korea and Australia have proliferated. Surely, the central question must be ‘Can the proliferation chain be terminated at that point?’ Thailand and the Philippines might begin to wonder if they should proliferate too, since other US allies are doing so. And Taiwan, which enjoys a security relationship governed by the Taiwan Relations Act rather than an actual treaty, might begin to harbour similar worries. As for other countries in the region, Indonesia might look askance at Australian proliferation. And Vietnam, living on China’s border, might think it should also begin considering a nuclear option. Read more

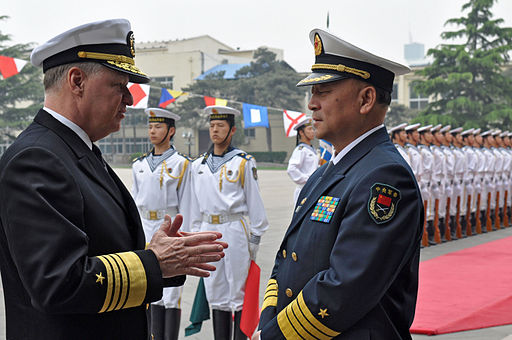

![U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi sit across from one another at a meeting at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing, China on February 14, 2014. [State Department photo/ Public Domain] U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi sit across from one another at a meeting at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing, China on February 14, 2014. [State Department photo/ Public Domain]](http://www.aspistrategist.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/12517148423_ff8fd08a9b_z.jpeg)