WPS and Talisman Sabre: learning from the past, looking to the future

This article is part of a series on ‘Women, Peace and Security’ that The Strategist is publishing in recognition of International Women’s Day 2017.

Exercise Talisman Sabre is Australia’s largest bilateral military exercise with our treaty ally, the United States. It takes place every two years, includes over 30,000 participants and is designed to enhance interoperability and build links to address shared threats within the Asia–Pacific region.

The United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (UNSCR1325) on Women, Peace and Security (WPS) was integrated into the exercise for the first time in 2015. The resolution looks at the different impact conflict has on women and girls and calls for their greater participation in conflict prevention and resolution. The integration of UNSCR1325 into Talisman Sabre is an important story because how we prepare for operations has a direct impact on how we behave in operations. Integrating gender considerations into exercises is an effective way to build understanding and test different approaches to operationalising UNSCR1325. In the lead-up to Talisman Saber ’17 in July, it’s timely to look back at what we learned last time and consider how we can continue to build on that work.

In mid-2014, a small group of civilian and military staff began advocating for the inclusion of UNSCR1325 into Talisman Sabre. Although this initial support came from the ground up, sustained support and engagement from Australian and US senior leadership ultimately made UNSCR1325 a key focus of the military exercise. That support ranged from statements to military commanders by Australia’s Foreign and Defence ministers and the US’s secretaries of State and Defense, highlighting the need to prioritise UNSCR1325 by specifically tasking staff. That reinforced UNSCR1325 as a foreign and security policy priority and created a strategic imperative that was difficult to ignore.

In a perfect world, integrating gender perspectives happens as “business as usual” with little to no guidance from above. However, we aren’t there yet. While grassroots movements continue to build support and demonstrate the utility of applying gender perspectives, sustained support from our national leaders via a top-down approach is still required. Diplomats and commanders alike must continue to keep UNSCR1325 central to their thinking, regularly drawing attention to it and issuing specific tasking to compel action.

Having a clear accountability framework for the integration of UNSCR1325 into Talisman Sabre was crucial. Following the release of Australia’s National Action Plan on WPS in 2012, the Australian Department of Defence developed an Implementation Plan, which specifically required the Australian Defence Force to integrate UNSCR1325 into exercises. Although there was a recognition of the principled importance of that task, having a clear reporting requirement was effective. Moving forward, there’s room to strengthen accountability around UNSCR1325. The next National Action Plan could pay particular attention to preparedness and explicitly outline how Australian government agencies can ensure UNSCR1325 is integrated into training, education and exercises. Civilian agencies could consider developing their own implementation plans that help translate strategic policy into agency-level work programs.

Integrating UNSCR1325 into Talisman Sabre highlighted a gap in soldiers’ training and education. Increasing baseline understanding about the resolution depended on a small number of specialists delivering ad-hoc presentations and sharing resources. Some staff were able to attend gender adviser training in Europe, but there was no domestic mechanism in place to train and educate a large group of people in Australia. The development of the Australian Military Gender Advisers Course is well-timed and will help to fill this gap. On the civilian side, there’s a plethora of training available on gender mainstreaming and gender in development, but there’s a gap when it comes to civilian-focused gender training for civil–military operations. With a Military Gender Advisers course in the pipeline, it might be worth considering whether civilian agencies should create something similar.

Talisman Sabre proved that integrating gender considerations into planning for operations requires a whole-of-government effort. In 2015, civilian advisers and military planners worked side-by-side to develop exercise products including the Commander’s Guide to Implementing UNSCR1325 into Military Planning. Such an approach ensured that exercise products were holistic and connected to broader political, diplomatic and humanitarian considerations.

But whole-of-government coordination doesn’t just happen, it requires proactive effort. To achieve such coordination, there’s room for civilian agencies to step-up their role in operationalising UNSCR1325. Building on Talisman Sabre ‘15, DFAT will dedicate two civilian Gender Advisers to Talisman Saber ‘17 to ensure consideration of civilian perspectives and priorities. The Department will also ensure that 50% of staff deployed to this exercise are female. By dedicating specific resources and ensuring equal participation in exercises, civilian agencies can have greater influence in how UNSCR1325 is conceived and planned for.

As we prepare for the next iteration of Talisman Saber, civil-military-police practitioners in Australia and the US need to remain focused on UNSCR1325. Although Talisman Sabre ‘15 highlighted how far we’ve come, it also demonstrated have far we have to go. We need to maintain strong leadership and build clearer accountability frameworks, develop more comprehensive training programs and proactively engage and invest in whole-of-government coordination. If we can do that, we’ll create the cultural and institutional change needed to ensure gender perspectives are applied in civil-military operations and enhance the on-the-ground outcomes for women, girls, men and boys.

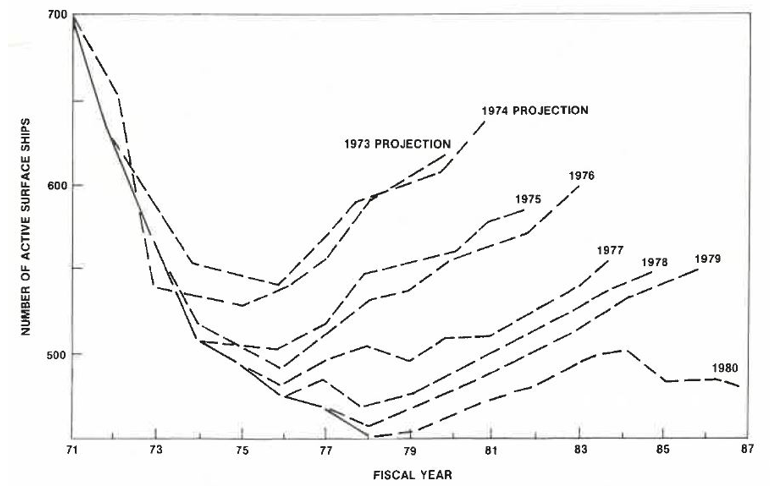

Source: Augustine’s Laws (1983)

Source: Augustine’s Laws (1983)