ASPI suggests

Welcome back to our weekly digest of current affairs.

To get the difficult bit out of the way first, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organisation has published a diagram showing the seismic signals of the six North Korean nuclear tests. The results demonstrate that the sixth nuclear test was particularly striking; it seems to have had a yield of 250-kt (250,000 tons of TNT equivalent) which is substantially larger than initial calculations. If you want to get an idea of what that really means, check out ‘Nukemap’. As for today’s missile test, let’s see if Serena Williams fires back…

Who are the women working in nuclear missile silos at Minot Air Force base in North Dakota? This piece and its accompanying video offers a humanising account of the work-life-balance for these women, complete with crochet, kids and pets.

We’re spoiled for choice when it comes to commentary on the current US administration. However, Eliot Cohen—former State Department counsellor—provides a sobering critique of US influence in the world and is well worth a read.

Moving on to other international trends of despondency, the renewed violence against the Rohingya communities in Myanmar shows no signs of relenting. This article from Council on Foreign Relations gives a good backgrounder of the recent events.

To finish our round up of international affairs, the now familiar commentary on the tangled web of Brexit negotiations makes for an interesting piece on the ‘Irish Question’. Finton O’Toole argues that an EU frontier between Britain and Ireland will inevitably have complex practical and ideological consequences that will require much more nuanced solutions than perhaps initially anticipated.

And now for something completely different. Whether as Mr Praline or Basil Fawlty, he’s been a permanent fixture in British comedy for half a century. Here’s an incredibly candid interview with John Cleese, with a good dose of familiar bad taste.

A good segue way into the new techy addition to Suggests (tech geek of the week), here’s an unusual museum review: a data crunch of the of the 2,229 paintings hanging in New York’s MoMa. (Cue the ‘yo MoMa’ jokes.) If you’ve ever wondered how MoMa keeps its collection ‘modern’, check out the statistical analysis done by FiveThirtyEight charting the year of a work’s acquisition versus the year it was painted.

Tech Geek of the Week by Malcolm Davis

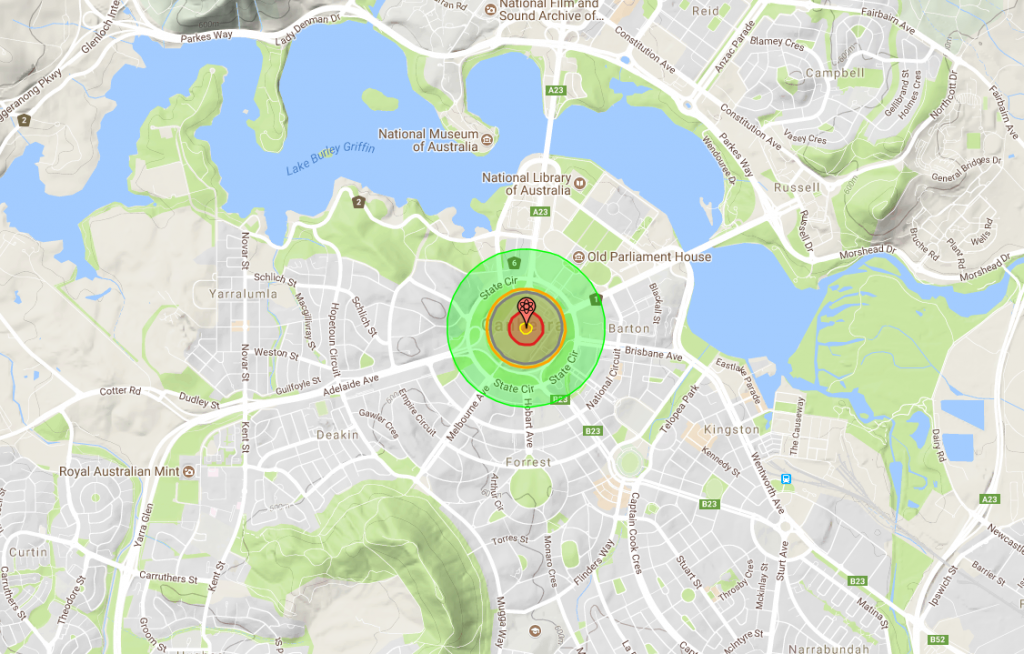

Let me introduce you to ‘Missilemap’. This feature from Nukemap allows you to simulate ballistic missile launches, including North Korean Hwasong 14 ICBMs. This week, while writing a piece on the Trump Administration’s interest in ‘Mini-nukes’, I used ‘Nukemap’ to virtually detonate the latest American nuke—a B61-12, which has ‘dial a yield’—on its lowest setting of 0.3kt over Parliament House in Canberra. The new security fence proved to be of little use but, amazingly, we all survived here at ASPI!

If mini-nukes aren’t your thing, then an interesting development in unmanned systems caught my eye. Rolls Royce don’t just make very cool (and very expensive) cars—they’ve proposed an autonomous warship piloted by artificial intelligence. The crewless vessel is designed to operate for over 100 days, and to have a range of 3,500 nm. They’re suggesting it might be perhaps 10-15 years away from being realised.

Finally, from the sublime to the ridiculous, the Russian media is claiming their T-14 Armata main battle tank can fight on Mars! Not sure who they’ll fight—the US NASA budget is so poor that there’s no money to get Americans to the Red Planet before the mid-2040s at least! Nor are there any Martians—at least not until Elon Musk gets there!

What we’re reading

This long read review of Oona Hathaway and Scott Shapiro’s ‘The Internationalists’ explores the history of multi-lateral peace treaties. It traces the pathways of modern political history and the competing ideas over the role of war in the global rules based order.

Dunkirk: retreat to victory, by Major General Julian Thompson, 2015.

Reviewed by Andrew Davies

Back in the news again because of Christopher Nolan’s recent film, the evacuation at Dunkirk has become an iconic piece of military history. But it has also been mythologised almost beyond recognition, largely thanks to the appeal of the ‘little boats’ image. In fact, most of the rescued soldiers were taken off by the Royal Navy, many of them on major surface combatants. And 70% of troops were embarked at the harbour rather than off the beaches.

The evacuation was the culmination of a short but ferocious campaign. Despite the title, the port of Dunkirk isn’t central to this book. In fact, it takes well over half of the book’s pages before the evacuation crystallises as the possible salvation of the British Expeditionary Forces (BEF), and even longer before it becomes clear that Dunkirk is the only viable location. That’s how it should be—the British forces didn’t deploy to France with the plan of evacuating three weeks after hostilities began, and several other ports were vital in British deployment planning. As the book makes clear, the undertrained BEF performed well under trying circumstances against a battle-hardened and better equipped adversary. The French and Belgian armies were poorly led and equally underprepared, and their underperformance effectively forced the British hand. The BEF’s short but bloody campaign was thus reduced to an able fighting retreat with a shrinking perimeter that finally ended at Dunkirk. The strength of the book is its ability to place a well-known (but poorly understood) event in proper context.

Videos

A Legacy of Valor: USS Somerset honours heroes of 9-11’s Flight 93

Check out Miss Texas slam Donald Trump’s equivocal condemnation of the perpetrators of the Charlottesville attack in just 15 seconds.

As populism and nationalism are on the rise, this discussion at the inaugural Women in the World Canada Summit explores the unique roles can women play in shaping the world.

Podcasts

For more on North Korea, check out this NPR interview with New Yorker writer Evan Osnos for his take on what the prospect of nuclear war means to the North Koreans he met in August this year.

Brexitexit? The Economist asks Liberal Democrat leader Vince Cable, can Britain ‘exit from Brexit’?

Events

Canberra: Initiatives for Women in Need is hosting their annual symposium on 16 September. This year’s theme is Preventing Terrorism: Understanding the Role of Women. Entry is free, details on the event page.

Canberra: ANU’s 2017 Indonesia update. Experts will be discussing ‘Indonesia in the new world: globalisation, nationalism and sovereignty’ over two days (15 and 16 September). Details here.