A very Trumpian year

At the end of 2017, US President Donald Trump’s administration and congressional Republicans rammed through a US$1 trillion cut in corporate taxes, partly offset by tax increases for the majority of Americans in the middle of the income distribution. But in 2018, the US business community’s jubilation over the handout started giving way to anxiety over Trump and his policies.

A year ago, US business and financial leaders’ unbridled greed allowed them to look past their aversion to large deficits. But they are now seeing that the 2017 tax package was the most regressive and poorly timed tax bill in history. In the most unequal of all advanced economies, millions of struggling American families and future generations are paying for tax cuts for billionaires. The United States has the lowest life expectancy among all advanced economies, and yet the tax bill was designed so that 13 million more of its people will go without health insurance.

As a result of the legislation, the US Department of the Treasury is now forecasting a US$1 trillion deficit for 2018—the largest single-year non-recessionary peacetime deficit in any country ever. And if that wasn’t bad enough, the promised increase in investment has not materialised. After giving a few pittances to workers, corporations have funnelled most of the money into stock buybacks and dividends. But this isn’t particularly surprising. Whereas investment benefits from certainty, Trump thrives on chaos.

Moreover, because the tax bill was rushed through, it is filled with mistakes, inconsistencies and special-interest loopholes that were smuggled in when no one was looking. The legislation’s lack of broad popular support all but ensures that much of it will be reversed when the political winds change, and this has not been lost on business owners.

As many of us noted at the time, the tax bill, along with a temporary increase in military spending, was not designed to give a sustained boost to the economy, but rather to provide the equivalent of a short-lived sugar high. Accelerated capital depreciation allows for higher after-tax profits now, but lower after-tax profits later. And because the legislation actually cut back on the deductibility of interest payments, it will ultimately increase the after-tax cost of capital, thus discouraging investment, much of which is financed by debt.

Meanwhile, the US’s massive deficit will have to be financed somehow. Given the country’s low saving rate, most of the money will inevitably come from foreign lenders, which means that the US will be sending large payments abroad to service its debt. A decade from now, total US income will most likely be lower than it would have been without the tax bill.

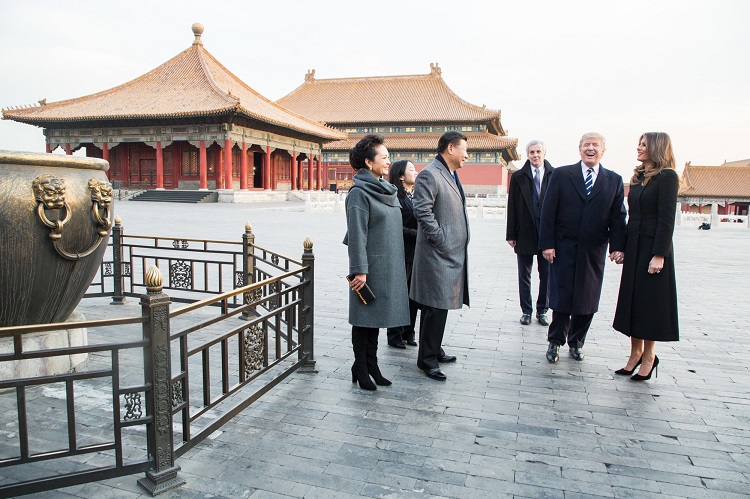

In addition to the disastrous tax legislation, the Trump administration’s trade policies are also unsettling markets and disrupting supply chains. Many US export businesses that rely on Chinese inputs now have a good reason to move their operations out of the US. It is too soon to tally the costs of Trump’s trade war, but it is safe to assume that everyone will be poorer as a result.

Likewise, Trump’s anti-immigrant policies are encouraging companies that depend on engineers and other high-skilled workers to move their research labs and production facilities abroad. It is only a matter of time before we start seeing worker shortages elsewhere in the US.

Trump came to power by exploiting the broken promises of globalisation, financialisation, and trickle-down economics. After a global financial crisis and a decade of tepid growth, elites were discredited, and Trump emerged to assign blame. But, of course, neither immigration nor foreign imports have caused most of the economic problems that he has exploited for political gain. The loss of industrial jobs, for example, is largely due to technological change. In a sense, we have been the victims of our own success.

Still, policymakers certainly could have managed these changes better to ensure that the growth of national income accrued to the many, rather than the few. Business leaders and financiers have been blinded by their own greed, and the Republican Party, in particular, has been happy to give them whatever they want. As a result, real (inflation-adjusted) wages have stagnated, and those displaced by automation and globalisation have been abandoned.

But if the economics of Trump’s policies weren’t bad enough, his politics are even worse. And, sadly, Trump’s brand of racism, misogyny and nationalist incitement has established franchises in Brazil, Hungary, Italy, Turkey and elsewhere. All of these countries will experience similar—or worse—economic problems, just as all are facing the real-world consequences of the incivility on which their populist leaders thrive. In the US, Trump’s rhetoric and actions have unleashed dark and violent forces that have already begun to spin out of control.

Society can function only when citizens have trust in their government, their institutions, and one another. And yet Trump’s political formula is based on eroding trust and maximising discord. One can only wonder where this will end. Is the murder of 11 Jews in a Pittsburgh synagogue the harbinger of an American Kristallnacht?

There is no way to know the answer to such questions. Much will depend on how the current political moment unfolds. If the supporters of today’s populist leaders grow disillusioned with the inevitable failure of their economic policies, they could veer even further towards the neo-fascist right. More optimistically, they could be brought back into the liberal-democratic fold, or at least become demobilised by their disappointment.

This much we do know: economic and political outcomes are intertwined and mutually reinforcing. In 2019, the consequences of the bad policies and worse politics of the last two years will come more fully into view.