Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

US tariffs on Chinese goods are approaching the levels that applied during the trade war of the 1930s but they’re being imposed on a much more complex set of trade and business relationships.

As much as 80% of global trade now takes place within corporate groups and is organised in ‘value chains’, where high-value work, such as research and marketing, is conducted in advanced countries and low-value assembly work is done in low-income developing nations.

In the 1930s, a company would consign goods to a shipping agent and an importing business would take delivery at the other end. International trade was a relatively small part of the global economy, accounting for around 10% of total output. However, the elevation of trade barriers, which started in the US with the Smoot-Hawley tariffs of 1930, nevertheless deepened the Depression as trade plunged to 5% of global GDP.

The recovery was slow, and trade didn’t get back to pre-Depression levels until the mid-1970s. But a series of developments from the mid-1980s onwards led to an explosion in trade volumes.

The major changes included the advent of shipping containers, huge improvements in communications technology, the breakdown of fixed exchange rates, the formation of the World Trade Organization and a global reduction in tariffs.

Trade reached an unprecedented peak of 27% of world GDP in 2008 on the eve of the global financial crisis. Trade volumes grew at double the rate of economic growth overall, and lifted prosperity across the world.

Literally billions of people from the developing world were drawn into the market economy as global businesses found ways of breaking the manufacture of complex goods into components that could be produced in different countries to maximise productivity while minimising labour cost.

The latest iPhone, for example, draws on components produced by 785 suppliers in 31 countries. Around half those suppliers are in China, while 60 are based in the US, including the American affiliates of foreign multinationals.

Many of the components supplied by US companies also use supplies from China and other Asian nations such as Taiwan, South Korea and Japan.

The Hong Kong–based company Li & Fung was a pioneer in using the power of communications and logistics management to distribute manufacturing operations across the Asian region, but most global firms were doing the same.

A Brookings Institution study shows that the increasing specialisation brought huge advances in productivity. Between 1995 and 2009, productivity in the US information technology industry rose by 200% as the share of its workforce with tertiary education rose from a third to half. As the US role in the industry shifted from production to design, the share of work carried out by low-skilled staff dropped from 10% to 5%.

In China, over the same period, productivity in the IT industry soared sixfold. Around 90% of the work was done by low- and medium -skilled labour, but the big gains in productivity were made possible by advanced capital equipment. The labour share in value-added dropped from more than 40% to about 30%.

The Trump administration is focusing on the gap between US exports to and imports from China and aspires to repatriate US investment abroad. However, business groups in the US and elsewhere have been driven by the profits to be won from a global market by using a global platform for production.

US firms employ a staggering 1.75 million staff in China, which is about 40% more than they have in either Mexico or Canada. They have committed US$400 billion to investments in China.

US affiliates in China are producing supplies for both global markets and the Chinese domestic market. Their total sales of US$345 billion are twice the size of US exports to China. The only countries where US multinationals have larger sales are Canada and Ireland, with the latter reflecting tax advantages.

Chinese firms have also invested heavily in the US with total assets of US$215 billion. They have gone to the US to access both its sophisticated market and its design and technology strengths. Their total workforce numbers only 80,000.

Analysis by the Peterson Institute for International Economics shows that average tariff levels on US imports from China have risen from 3.1% in 2017 to 18.3% now.

The latest measures proposed by the Trump administration would lift average tariff levels to 27.8%, which compares to levels of around 30% during the Depression.

Until now, most of the US tariffs have been on capital goods and ‘intermediate’ goods, or components used by industry. The latest round includes most of China’s vast array of consumer goods and is expected to add around 0.5 percentage points to US inflation. The price of an iPhone in the US is expected to rise by about US$160, according to a Morgan Stanley report.

The tariffs on capital and intermediate goods are effectively a tax on US industry and reduce its competitiveness.

Modelling suggests this loss of competitiveness would reduce US exports by 6% over the next decade, quite apart from the loss of bilateral trade between China and the US.

Companies are working to reorganise their supply chains to avoid the impact of the tariffs. A survey by law firm Baker McKenzie found that 18% of multinationals in China were completely shifting their supply and production from China and a further 58% were making major changes. Many are moving production to other countries in Southeast Asia, including Cambodia, Indonesia and Vietnam.

Companies exporting from the US to China are also having to reconsider their operations. China’s 25% retaliatory tariff on US motor vehicles will affect annual sales of around 270,000 vehicles, with the US subsidiaries of German manufacturers accounting for US$7 billion of the US$11 billion of total vehicle exports.

The OECD argues that the best measure of trade flows looks at the value added in the exporting country, rather than at the gross sales proceeds. If China exports an iPhone worth $1,000, but $900 of the value contained within it comes from the US, the OECD would credit China with only $100.

The OECD estimates that 12.6% of the value added to the US economy from its exports comes from its sales to China, more than any other country. For China, the US delivers just under a quarter of the wealth it obtains from exports.

Unscrambling the linkages between the US and Chinese economies is likely to come at a heavy cost to both.

There’s a growing debate in policy circles right now: are cyber technologies good or bad for democracy? Are internet platforms weakening public debate and social cohesion? Will artificial intelligence inevitably favour tyranny?

What’s often missing from this debate is a nuanced appreciation of culture. Every piece of technology is invented by humans and for humans. Whether a technology has ‘good’ or ‘bad’ effects can depend on the social and political context it came from.

Most of the cyber technologies we use today reflect the values of Silicon Valley elites and the American government’s light-touch approach to the tech sector. American tech has enabled significant good, but the values baked into it have also proved toxic—something that we’re only now beginning to understand.

But America is losing its technological supremacy. China is poised to lead on AI, 5G and quantum computing, while its firms are increasingly dominant in consumer-facing platforms, from e-commerce and online payments to social media and gaming. American and Chinese technologies necessarily embody different value systems; understanding both will be essential to navigating the social and geopolitical consequences of technological progress.

The internet started life as a network for sharing resources between American researchers. Its pioneers prioritised openness; they didn’t design security into the network because that would have slowed traffic down. But this feature became a flaw as the internet expanded. Any internet-enabled device is now vulnerable to being hacked. In addition, because advertising was the only way to make money on a network designed to be free and open, surveillance became, in Bruce Schneier’s words, ‘the business model of the internet’.

Today’s internet platforms also reflect America’s unique cultural mix of muscular capitalism and hyper-individualism. Is it really a surprise that the country whose advertising industry convinced people to smoke tobacco and drink Coke turned the internet into a global tracking machine designed to make people buy more things? Or that the culture that brought us narcissism-as-celebrity through the likes of Kim Kardashian also created Instagram—where #me is always trending?

Recent advances in AI have underscored how cultural context infects technology. Machine-learning tools used by courts to inform parole decisions have been shown to be systematically biased against African Americans. Until recently, when Facebook users searched for ‘pictures of my female friends’, the platform would prompt them to look at bikini shots. These tools were not designed to discriminate. However, because they were ‘trained’ on real-world data, they hold a mirror to a culture that is, regrettably, racist and sexist.

Smaller countries that are technology ‘takers’ have long had to grapple with the downsides of American tech.

For example, because of their advertising-driven revenue model, social media platforms seek to maximise user attention—often by prioritising divisive and emotionally charged content. In America, this feature has exacerbated polarisation and identity politics. But for countries with ethnic tensions and weak institutions, American social media algorithms are fuelling actual violence. Online rumours and hate speech have sparked race-hate attacks against Muslims in Sri Lanka and spates of religious violence in India, and contributed to the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya in Myanmar.

American platforms also reflect the libertarian worldviews of many Silicon Valley engineers, including the belief that unfettered free speech is nearly always a net positive for democracy. This has long rankled Europeans, whose own political values and history have caused them to view privacy as a human right and understand the perils of hate speech. In this respect, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation can be seen as an effort to bend American tech to European values.

Awareness of the downsides of American tech is growing, but discussion about the values likely to shape Chinese tech is less advanced. What is clear is that these values will not be identical to those that have guided American tech. In the words of Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei, ‘We have our own value system. We don’t accept the Western political value system completely.’

Management theory has long maintained that China is a relational culture, where duty to family and the state is prioritised over individual rights. It’s therefore unsurprising that Chinese platforms don’t emphasise free expression and privacy—and that trend is likely to continue.

China is also a historically ‘low-trust’ society, which helps to explain the emergence of China’s ‘social credit’ system and its apparent strong domestic support. Many in the West perceive social credit as simply government control of Orwellian proportions, but it may also help bridge China’s trust deficit by providing incentives for—and evidence of—citizens’ and officials’ lawfulness and integrity.

As Bing Song recently argued, most Western analysis of social credit also fails to appreciate Chinese society’s longstanding tradition of using government structures to ‘promot[e] moral behavior’. Given this context, we should expect Chinese platforms to nudge users to comply with the party-state’s notions of ‘morality’, and to prioritise transparency about user identity and activity over notions of anonymity or privacy.

It’s also instructive to look at the Chinese tech sector’s culture. As venture capitalist Kai-Fu Lee has outlined, China’s relatively weak property protections meant that its tech pioneers faced a hypercompetitive ‘coliseum’. Kill-or-be-killed tactics, not lofty Silicon Valley ‘mission statements or “core values”’, were the key to survival—as was a fanatical work ethic that would have had American engineers ‘running to their nap pods’. It’s not surprising, then, that Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei, known today for its ‘wolf culture’, allegedly paid bonuses to staff who stole trade secrets. Chinese tech’s win-at-all-costs mentality will continue to shape the sector’s conduct and products.

Finally, the Chinese Communist Party seeks to exert control over its population’s digital experience. It does this by introducing laws, inserting itself into corporate hierarchies and rewarding tech executives who demonstrate party loyalty. As a result, the top tech firms tend to reflect the CCP’s values; New York Times journalist Li Yuan recently said of Huawei that its ‘soul is steeped in Communist Party culture’.

The future trajectory of technology is not a given. Technology takers including Australia must ask ourselves: what values do we want reflected in the technologies we use, and what costs are we prepared to incur to guarantee this? We then must identify the levers available to us to influence technology powers like America and China, and their companies.

American companies are subject to the rule of law, are accountable to regulators and can be motivated to change by activists and public opinion. We have fewer levers available to shape Chinese technologies—a reality that should make us even more determined to understand their latent values.

US President Donald Trump’s administration has shown little interest in public diplomacy. And yet this form of diplomacy—a government’s efforts to communicate directly with other countries’ publics—is one of the key instruments policymakers use to generate soft power.

The information revolution makes such instruments more important than ever.

Opinion polls and the Portland ‘Soft Power 30’ index show that American soft power has declined since the beginning of Trump’s term. Tweets can help to set the global agenda, but they do not produce soft power if they are not attractive to others.

Trump’s defenders reply that soft power—what happens in the minds of others—is irrelevant; only hard power, with its military and economic instruments, matters. In March 2017, Trump’s budget director, Mick Mulvaney, proclaimed a ‘hard power budget‘ that would have slashed funding for the State Department and the US Agency for International Development by nearly 30%.

Fortunately, military leaders know better. In 2013, General James Mattis, who would later become Trump’s defence secretary, warned Congress, ‘If you don’t fund the State Department fully, then I need to buy more ammunition ultimately.’ As Henry Kissinger once pointed out, international order depends not only on the balance of hard power, but also on perceptions of legitimacy, which depends crucially on soft power.

Information revolutions always have profound socioeconomic and political consequences—witness the dramatic effects of Gutenberg’s printing press on Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries. One can date the current information revolution from the 1960s and the advent of ‘Moore’s law’, which states that the number of transistors on a computer chip doubles roughly every two years. As a result, computing power increased dramatically, and by the beginning of this century cost 0.1% of what it did in the early 1970s.

In 1993, there were about 50 websites in the world; by 2000, that number surpassed five million. Today, more than four billion people are online; that number is projected to grow to 5–6 billion people by 2020, and the ‘internet of things’ will connect tens of billions of devices. Facebook has more users than the populations of China and the US combined.

In such a world, the power to attract and persuade becomes increasingly important. But long gone are the days when public diplomacy was mainly conducted through radio and television broadcasting. Technological advances have led to a dramatic reduction in the cost of processing and transmitting information. The result is an explosion of information, which has produced a ‘paradox of plenty’: an abundance of information leads to scarcity of attention.

When the volume of information confronting people becomes overwhelming, it is hard to know what to focus on. Social media algorithms are designed to compete for attention. Reputation becomes even more important than in the past, and political struggles, informed by social and ideological affinities, often centre on the creation and destruction of credibility. Social media can make false information look more credible if it comes from ‘friends’. As US Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report on Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election showed, this enabled Russia to weaponise American social media.

Reputation has always mattered in world politics, but credibility has become an even more important power resource. Information that appears to be propaganda may not only be scorned, but may also turn out to be counterproductive if it undermines a country’s reputation for credibility—and thus reduces its soft power. The most effective propaganda is not propaganda. It is a two-way dialogue among people.

Russia and China do not seem to comprehend this, and sometimes the United States fails to pass the test as well. During the Iraq War, for example, the treatment of prisoners at Abu Ghraib in a manner inconsistent with American values led to perceptions of hypocrisy that could not be reversed by broadcasting pictures of Muslims living well in America. Today, presidential tweets that prove to be demonstrably false undercut America’s credibility and reduce its soft power. The effectiveness of public diplomacy is measured by minds changed (as reflected in interviews or polls), not dollars spent or number of messages sent.

Domestic or foreign policies that appear hypocritical, arrogant, indifferent to others’ views or based on a narrow conception of national interest can undermine soft power. For example, there was a steep decline in the attractiveness of the US in opinion polls conducted after the invasion of Iraq in 2003. In the 1970s, many people around the world objected to the US war in Vietnam and America’s global standing reflected the unpopularity of that policy.

Sceptics argue that such cycles show that soft power does not matter much; countries cooperate out of self-interest. But this argument misses a crucial point: cooperation is a matter of degree, and the degree is affected by attraction or repulsion.

Fortunately, a country’s soft power depends not only on its official policies, but also on the attractiveness of its civil society. When protesters overseas were marching against the Vietnam War, they often sang ‘We shall overcome’, an anthem of the US civil rights movement. Given past experience, there is every reason to hope that the US will recover its soft power after Trump, though a greater investment in public diplomacy would certainly help.

In this episode, Brendan Nicholson talks cybersecurity with the former chief of both the US National Security Agency and Cyber Command, and now distinguished visiting fellow with ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre, Admiral Mike Rogers. See here for an in-depth Strategist piece on the interview.

Later in the podcast, Renee Jones talks to Malcolm Davis and Hannah Smith about the tactics used in the Battle of Winterfell on Game of Thrones and the strategic implications for the rest of the show’s final series.

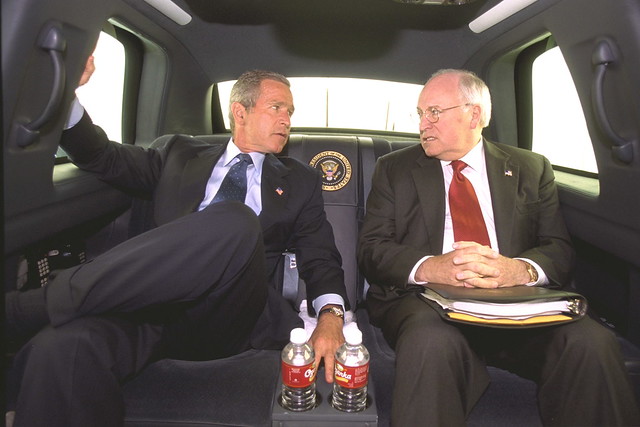

It was John Nance Garner, Franklin Roosevelt’s first vice president, who characterised his office most pithily and dismissively. The formidable Texas Democrat, ‘cactus Jack’, declared that the vice presidency of the United States was ‘not worth a bucket of warm spit’.

Historically, the vice presidency has often been so derided. Asked what Vice President Richard Nixon had contributed on a particular policy issue, President Dwight Eisenhower deadpanned that he needed a couple of weeks to consider the question. Indeed, Nixon discovered that, as vice president, he wasn’t actually a member of the government.

Perhaps this explains why Harry Truman knew nothing of the Manhattan Project, through which America developed the atomic bomb, until he actually assumed the presidency on FDR’s death in April 1945. The vice president was that remote from White House decision-making.

Much has changed for the better since then, particularly given the more assertive nature of vice presidents from Walter Mondale to Joe Biden, through the likes of George H.W. Bush, Al Gore and Dick Cheney. When he was vice president, George H.W. Bush, understanding the dangers of being excluded from the centre of power, insisted on a weekly lunch with the president, Ronald Reagan.

But few vice presidents, at least since Aaron Burr, have accumulated and exercised power after the fashion of Cheney. He’s now the subject of a splendid film, Vice, that is part satire and part drama but always engaging.

The movie is hardly a biopic and it certainly isn’t history. Like The Iron Lady, which centred on Margaret Thatcher in decline, Vice has a point to make about Cheney and his years in power and approaches the subject from a liberal perspective. But there’s something in the movie to interest most, from the farcical to the infuriating, and from the disarming to the depressing.

The cast is uniformly impressive, with Christian Bale mesmerising as Cheney, plastered in makeup but having mastered the VP’s distinctive mannerisms, including his facial tics.

Similarly, Steve Carrell as Donald Rumsfeld gives a superb performance, driven by the defence secretary’s cynicism and ruthlessness in both internal struggles and policy battles. Originally Cheney’s mentor and promoter, Rumsfeld in his fall from grace offers a salutary lesson to all who aspire to great office.

George W. Bush can’t possibly have been as shallow a lightweight as portrayed by Sam Rockwell. It is a portrait that accords with the popular assessment of the 43rd president, but it would be wrong to accept it at face value, given Bush’s electoral record both as governor of Texas and as president. His success can’t all be down to Karl Rove.

But it’s Amy Adams, as the feisty Lynne Cheney, who steals this movie. It is Lynne who saves Cheney from a dissolute, brawling lifestyle in Casper, Wyoming, causing him to clean up his act, finish college and set out on a Republican political pathway. Rather like the contribution made by the able Laura Bush in her husband’s progress to sobriety and seriousness, Lynne Cheney is a primary character in this film.

Directed by Adam McKay, Vice is an outstanding offering for a broad audience, but there are particularly interesting insights for strategic analysts.

Within the Nixon White House, the president quietly conspired with Henry Kissinger to initiate a secret bombing campaign in Cambodia. The consequences for the Cambodian people were devastating. The bombing was never disclosed to Congress and became another avenue of impeachment for Nixon.

Similarly, the Bush administration’s decision to invade Iraq is shown in terms of ideological and personal imperative, despite the lack of credible intelligence on Saddam Hussein’s arsenal or intentions. Colin Powell (Tyler Perry) is sceptical but is obliged to speak at the United Nations Security Council and denounce Saddam. In the years after, Powell regarded the speech as the worst he ever made.

The Bush White House’s treatment of intelligence and its brutal response to critics may be painted in harsh colours, but there’s more than a kernel of truth in what is on the screen, given the legal travails of the vice president’s chief of staff, Scooter Libby.

Congresswoman Liz Cheney of Wyoming is now chair of the House Republican Conference, the third-ranking Republican in the House of Representatives. Her sister Mary is depicted as suffering rejection to further Liz’s ambitions. They play politics tough in the open spaces of Wyoming.

The current vice president, Mike Pence, often acts as the Trump administration’s sweeper, bringing coherence to policy tweets by the president. In particular, Pence has been sharply critical of Chinese ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ and forthright in opposition to the Maduro regime in Venezuela.

That a Republican vice president can take such a role owes much to Dick Cheney, who assumed a position in American government—especially in national security after 9/11—that was powerful in every dimension.

Vice is political cinema at its best: robust and confronting while telling a tale of power in practice.

The United States responded weakly after Russian cyber operations disrupted the 2016 presidential election. US President Barack Obama had warned his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, of repercussions, but an effective reply became entangled in the domestic politics of Donald Trump’s election. That could be about to change.

Recently, American officials anonymously acknowledged that US offensive cyber operations prevented a Kremlin troll farm from disrupting the 2018 congressional elections. Such offensive cyber operations are rarely discussed, but they suggest ways to deter disruption of the US presidential election in 2020. Attacking a troll farm will not be enough.

Deterrence by threat of retaliation remains a crucial but underused tactic for preventing cyberattacks. There has been no attack on US electrical systems, despite the reported presence of Chinese and Russians on the grid. Pentagon doctrine is to respond to damage with any weapon officials choose, and deterrence seems to be working at that level.

Presumably, it could also work in the grey zone of hybrid warfare, such as Russia’s disruption of democratic elections. Given that US intelligence agencies are reported to carry out espionage in Russian and Chinese networks, one can imagine that they discover embarrassing facts about foreign leaders’ hidden assets, which they could threaten to disclose or freeze. Similarly, the US could go further in applying economic and travel sanctions against authoritarians’ inner circles. The diplomatic expulsions and indictments since 2016, and the recent offensive actions, were only first steps towards strengthening America’s deterrent threat of retaliation.

But deterrence will not be enough. The US will also need diplomacy. Negotiating cyber arms-control treaties is problematic, but this does not make diplomacy impossible. In the cyber realm, the difference between a weapon and a non-weapon may come down to a single line of code, or simply the intent of a computer program’s user. Thus, it will be difficult to prohibit the design, possession, or even implantation for espionage of particular programs. In that sense, cyber arms control cannot be like the nuclear arms control that developed during the Cold War. Verification of weapons stockpiles would be virtually impossible, and even if it were assured, stockpiles could quickly be recreated.

But if traditional arms-control treaties are unworkable, it may still be possible to set limits on certain types of civilian targets, and to negotiate rough rules of the road that minimise conflict. For example, the US and the Soviet Union negotiated an Incidents at Sea Agreement in 1972 to limit naval behaviour that might lead to escalation. The US and Russia might negotiate limits to their behaviour regarding each other’s domestic political processes. Even if there is no agreement on precise definitions, they could exchange unilateral statements about areas of self-restraint and establish a consultative process to contain conflict. Such a procedure could protect democratic non-governmental organisations’ right to criticise authoritarians while at the same time creating a framework that limits governmental escalation.

Sceptics object that such an arrangement is impossible, owing to the differences between American and Russian values. But even greater ideological differences didn’t prevent agreements related to prudence during the Cold War. Sceptics also say that Russia would have no incentive to agree, because elections are meaningless there. But this ignores the potential threat of retaliation: democratic openness means the US has more to lose in the current situation, which should encourage it not to hold back from pursuing its self-interest in developing a norm of restraint in this grey area.

Jack Goldsmith of Harvard Law School has argued that the US needs to draw a principled line and defend it. That defence would acknowledge that the US has itself interfered in elections, renounce such behaviour, and pledge not to engage in it again. The US should also acknowledge that it continues to engage in forms of computer network exploitation for purposes it deems legitimate. And officials should ‘state precisely the norm that the United States pledges to stand by and that the Russians have violated’.

This would not be unilateral disarmament on America’s part; rather, it would draw a line between the permitted soft power of open persuasion and the hard power of covert information warfare. Overt programs and broadcasts would continue to be allowed. The US would not object to the content of Russia’s open political speech, including the propagandistic RT television network. But it would object when Russia promotes its views through covert coordinated behaviour such as the 2016 manipulation of social media, or dumping hacked emails.

Non-state actors often act as state proxies in varying degrees, but the rules would require their open identification. And because the rules will never be perfect, they must be accompanied by a consultative process that establishes a framework for warning and negotiation. Such a process, together with stronger deterrent threats, is unlikely to fully stop Russian interference, but if it reduces the level, it could enhance America’s defence of its democracy.

Given the poor state of US–Russian relations, with Putin boasting about new nuclear weapons, the climate for an agreement is not promising, though there have been some hints of Russian interest. At the same time, the partisan divisions in US politics over the legitimacy of Trump’s relationship with Russia also make negotiations difficult. If both sides want to avoid dangerous escalation, perhaps the possibilities can be explored in the context of a professional or military-to-military dialogue. Or the idea may just have to wait until after the 2020 election.

The dysfunctional politics of Brexit in the United Kingdom, and the midterm election reaction against President Donald Trump in the United States, are generating second thoughts about the populist tide that has been sweeping the world’s democracies in recent years. In fact, second thoughts are long overdue.

Populism is an ambiguous term applied to many different types of political parties and movements, but its common denominator is resentment of powerful elites. In the 2016 presidential election, both major US political parties experienced populist reactions to globalisation and trade agreements. Some observers even attributed Trump’s election to the populist reaction to the liberal international order of the past seven decades. But that analysis is too simple. The outcome was determined by many factors, and foreign policy was not the main one.

Populism is not new, and it is as American as apple pie. Some populist reactions—for example, Andrew Jackson’s presidency in the 1830s or the Progressive Era at the beginning of the 20th century – have led to democracy-strengthening reforms. Others, such as the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic Know-Nothing Party in the 1850s or Senator Joe McCarthy and Governor George Wallace in the 1950s and 1960s, have emphasised xenophobia and exclusion. The recent wave of American populism includes both strands.

The roots of populist reactions are both economic and cultural, and are the subject of important social science research. Pippa Norris of Harvard and Ronald Inglehart of the University of Michigan have found that cultural factors long antedating the 2016 election were very important. Voters who lost jobs to foreign competition tended to support Trump, but so did groups like older white males who lost status in the culture wars that date back to the 1970s and involved changing values related to race, gender and sexual preference. Alan Abramowitz of Emory University has shown that racial resentment was the single strongest predictor for Trump among Republican primary voters.

But economic and cultural explanations are not mutually exclusive. Trump explicitly connected these issues by arguing that illegal immigrants were taking jobs from American citizens. The symbolism of building a wall along America’s southern border was a useful slogan for uniting his electoral base around these issues. That is why he finds the idea hard to give up.

Even if there had been no economic globalisation or liberal international order, and even if there had been no great recession after 2008, domestic cultural and demographic changes in the US would have created some degree of populism. America saw this in the 1920s and 1930s. Fifteen million immigrants had come to the US in the first 20 years of the century, leaving many Americans with an uneasy fear of being overwhelmed. In the early 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan had a resurgence and pushed for the National Origins Act of 1924 to ‘prevent the Nordic race from being swamped’, and ‘preserve the older, more homogeneous America they revered’.

Similarly, Trump’s election in 2016 reflected rather than caused the deep racial, ideological and cultural schisms that had been developing in reaction to the civil rights and women’s liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Populism is likely to continue in the US as jobs are lost to robotics as much as to trade, and cultural change continues to be divisive.

The lesson for policy elites who support globalisation and an open economy is that they will have to pay more attention to issues of economic inequality as well as adjustment assistance for those disrupted by change, both domestic and foreign. Attitudes towards immigration improve as the economy improves, but it remains an emotional cultural issue. In mid-2010, when the effects of the great recession were at their peak, a Pew survey found that 39% of US adults believed immigrants were strengthening the country, and 50% viewed them as a burden. By 2015, 51% said that immigrants strengthen the country, while 41% said they were a burden. Immigration is a source of America’s comparative advantage, but political leaders will have to show that they can manage national borders—both physical and cultural—if they are to fend off nativist attacks, particularly in times and places of economic stress.

Still, one should not read too much about long-term trends in American public opinion into the heated rhetoric of the 2016 election or Trump’s brilliant use of social media to manipulate the news agenda with cultural wedge issues. While Trump won the Electoral College, he fell three million short in the popular vote. According to a September 2016 poll, 65% of Americans thought that globalisation was mostly good for the US, despite their concerns about jobs. While polls are always susceptible to framing by altering the wording and order of questions, the label ‘isolationism’ is not an accurate description of current American attitudes.

Since 1974, the Chicago Council on Global Affairs has asked Americans annually if the US should take an active part in, or stay out of, world affairs. Over that period, roughly a third of the public has been consistently isolationist, harking back to the 19th-century tradition. That number reached 41% in 2014, but, contrary to popular myth, 2016 was not a high point of post-1945 isolationism. At the time of the election, 64% of the respondents said they favored active involvement in world affairs, and that number rose to 70% in the 2018 poll, the highest recorded level since 2002 (which had been reached in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks).

Strong support for immigration and globalisation in the US sits uneasily with the view that ‘populism’ is a problem. The term remains vague and explains too little—particularly now, when support for the political forces it attempts to describe seems to be on the wane.

On 17 January, US President Donald Trump went down to the Pentagon to speak at the launch of his administration’s long-awaited Missile Defense Review (MDR). The MDR is the previously missing fourth wheel of the administration’s security policy, and fits naturally alongside the earlier three: the National Security Strategy, the National Defense Strategy and the Nuclear Posture Review.

Trump’s speech wasn’t his finest—at times it teetered on the brink of incoherence. (The text can be found here, or you can watch it here (Trump comes on at around 11.50).) The president was distracted by all his favourite hobbyhorses: the size of his defence budgets, the migrant caravans heading towards the US–Mexico border, and the fecklessness of penny-pinching allies, to name just a few. Still, every now and then he returned to the topic du jour, usually in sweeping terms.

[W]e will terminate any missile launches from hostile powers, or even from powers that make a mistake … Regardless of the missile type or the geographic origins of the attack, we will ensure that enemy missiles find no sanctuary on Earth or in the skies above.

Our strategy is grounded in one overriding objective: to detect and destroy every type of missile attack against any American target, whether before or after launch.

Those are grand objectives for a limited and imperfect technology. And, mercifully, that’s not what the MDR actually says. But what it does say is a significant and important expansion of previous policy settings. With the potential global reach of America’s future sensor array and interception capabilities, the review certainly points the way to a much larger footprint for US missile defence. And, of course, this is a missile defence review, and not simply a ballistic-missile defence review; the emergence of new types of missile is complicating the defender’s task.

But there’s one aspect of the MDR that I want to explore more closely, and that’s what it says—and doesn’t say—about Russia and China. After all, this is the first missile defence review since the US formally left the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002 that has been required to address a security environment in which Russia and China are identified as strategic competitors for the US. In the 2010 Ballistic Missile Defense Review, remember, the US observed that, ‘With Russia, it [was] pursuing a broad agenda focused on shared early warning of missile launches, possible technical cooperation, and even operational cooperation. With China, the Administration [sought] further dialogue on strategic issues of interest to both nations, including missile defence.’

Like its 2010 predecessor, the 2019 MDR splits its consideration of the missile-defence mission into two parts: defence of the US homeland from ICBM-level threats on the one hand, and defence of deployed US forces, allies and partners from regional missile threats on the other. And, again like its predecessor, it uses the baseline established by the offensive threat posed to the US homeland by rogue states—namely, North Korea and Iran—to answer the tricky question of how much the US ground-based midcourse defence system should be expected to handle. That system was never intended to cope with a large, sophisticated missile barrage from Russia or China. It was built to take the ‘cheap shots’ from rogue powers off the table.

The language varies much more, however, on regional missile threats. The 2010 review canvasses the threats posed by North Korea in Northeast Asia and by Iran and Syria in the Middle East. The 2019 MDR canvasses the regional threats posed by North Korea, Iran, Russia and China. And here’s the rub: regional missile threats are treated in the same way as rogue-state threats to the US homeland.

[T]he missile threat environment now calls for a comprehensive approach to missile defence against rogue state and regional missile threats. This approach integrates offensive and defensive capabilities for deterrence, and includes active defense to intercept missiles in all phases of flight after launch, passive defense to mitigate the effects of missile attack, and attack operations during a conflict to neutralize offensive missile threats prior to launch.

That ‘integrated approach’ needn’t automatically mean that the US will—during a conflict—attempt to pre-emptively attack Russian and Chinese regional-range missiles prior to launch. But it does put both countries on notice that the US hasn’t ruled out that possibility. It’s possible that the MDR may have been written deliberately to send that message. Russia’s ‘escalate to de-escalate’ doctrine, after all, is a strategy built for regional coercion, rather than a strategy aimed at the US homeland.

Still, this is an area where all three great powers will probably want to tread carefully. During the Department of Defense’s off-camera press briefing on the MDR, a number of officials spoke cautiously about pre-emption scenarios, generally stressing that various military options remained a part of any military doctrine, but emphasising that deterrence and defence were the main purposes of missile defence. That’s true, but competitive great-power relationships are pulling us towards a new and unfamiliar strategic order. Since the end of the Cold War, almost 30 years ago, we’ve become used to—grudging—great-power cooperation. That condition no longer applies.

China has become something of a punching bag for Western criticism. At the East Asia Summit in Singapore last year, US Vice President Mike Pence insinuated that China is pushing ‘empire and aggression’ in the Indo-Pacific. Disgruntlement with China dominated November’s Stockholm China Forum meeting, a gathering of American, Chinese and European ambassadors, diplomats, scholars, politicians and business leaders. Whether it’s the ‘debt trap’ of its Belt and Road Initiative, island building in the South China Sea or alleged influence operations, China is causing profound anxiety in Western democracies. Has China become a great disrupter?

There are reasons to think that global stability is still in the interest of a powerful China and that Chinese leaders will come to appreciate that insight. In an age of ambition, Beijing is unwilling to make absolute stability its foreign policy goal; but it also doesn’t want unremitting competition or confrontation.

President Xi Jinping refers to the aim of his grand strategy as the ‘great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’. In his report to the 19th party congress, Xi divides China’s rise into three periods: standing up under Mao, getting rich under Deng Xiaoping, and becoming powerful under himself.

It is true that stability isn’t posited as a goal in itself, but it is well worth asking whether national rejuvenation can be achieved without a good degree of external stability. Xi’s rejuvenation project, although above all a domestic task, also requires a reasonably stable regional and international environment. A turbulent world would create many challenges. The international structural imperative is such that even if Chinese policy creates instability in certain areas and at certain times, decision-makers will try to keep it under control and recognise the virtue of overall stability.

Does stability have a place under the overarching goal of national rejuvenation? In an important foreign policy speech delivered in June 2018, Xi described the ‘layout’ of his strategy, composed of six arenas. The first is to make the global governance system fairer and more reasonable. The second is to solidify the BRI. The third is to ‘construct a framework of overall stability and balanced development’ for the major powers. The fourth is to improve neighbourhood diplomacy and make the regional environment friendlier and more beneficial to China. The fifth is to deepen cooperation with developing countries. And the sixth is to promote mutual interaction and mutual learning with the rest of the world.

Each arena of this strategic roadmap assumes stability as an objective. Take two critical areas: major-power relations and neighbourhood policy. For major-power relations, overall stability is identified as a key goal. Indeed, Xi’s China desperately wants to stabilise relations with the US, now buffeted by President Donald Trump’s trade war and other uncertainties. For neighbourhood policy, the goal is a friendlier regional environment, which can’t be achieved without a good degree of stability. Beijing is now trying hard to bring stability back to the South China Sea by negotiating a code of conduct with Southeast Asian nations. At the level of grand strategy, China has built in overall stability as a foreign policy goal.

But grand strategy is as much about implementation as about conception, and successful implementation is by no means an easy matter. Here we should note the powerful mechanism of learning. During Xi’s first term, his ambitious and assertive regional policy was destabilising, especially in the East and South China Seas. But notable changes have taken place recently. In the South China Sea, for example, Chinese island-building increased security tension, but the code-of-conduct negotiations represent an attempt from Beijing to achieve a balance between regional stability and national rights. It is based on the recognition that despite all the nationalist fervour about sovereignty and maritime rights, stability is still an important foreign policy interest.

Another case in point is an important debate within China about strategic overstretch. Launched by Renmin University professor Shi Yinhong, among others, the debate brings to the fore the costs of Xi’s assertiveness. It may have already influenced official thinking.

The BRI provides a further example. Although unwilling to accept the ‘debt trap’ criticism, Beijing is privately acknowledging the problem of debt in some BRI projects and has courted collaboration on infrastructure investment from third parties such as Singapore and Japan.

International concerns about the challenge posed by Xi’s plans are understandable. Ambitions aside, China still has a strong incentive to achieve a good degree of external stability. International interdependence is a structural imperative and Xi and his team have learned and will continue to learn about the virtue of stability through a policy process of trial and error. Ultimately, China is far more likely to balance its goals in the service of overall stability than to wreak havoc.

Chinese leaders do like their slogans, and where foreign policy is concerned, two have reflected Beijing’s thinking in recent times. The first is the cautious principle of tao guang yang hui, usually rendered in English as ‘hide your light and bide your time’, which guided Chinese policy for decades after Deng Xiaoping established it in the 1980s. In late 2013, though, President Xi Jinping coined a new slogan to define a more assertive, muscular approach: fen fa you wei, or ‘strive for achievement’.

The drift towards a more assertive foreign policy under Xi has been evident everywhere, from China’s declaration of an air defence identification zone over the East China Sea in late 2013, to the creation of ‘facts on the ground’ in the South China Sea, to the development of the Belt and Road Initiative.

But recently there have been signs that China might be having second thoughts about its ability to keep striving for achievement. Xi’s government seems clearly to have entered concession-making mode in its relations with the United States, and some prominent Chinese academics have begun questioning whether China has been guilty of strategic overstretch. For example, Yan Xuetong, a doyen of Chinese foreign-policy scholarship, has recently argued that Xi has gone too far, and that China should limit its ambitions to a narrower, regional sphere. Another Beijing-based expert, Shi Yinhong, calls for ‘strategic retrenchment’ in Chinese foreign policy.

An easy explanation for this Chinese shift towards retrenchment is US President Donald Trump, who has applied his own brand of assertiveness to the US–China relationship, with the apparent support of the entire American political class and much of Europe’s, too. Confronted by pushback from the West, China is unsurprisingly warier of pushing forward.

But China’s current caution also owes much to the fragility of its economic performance. As anyone who has recently travelled to Beijing will tell you, the sense of economic pessimism there has rarely been as tangible as it is now.

To a degree, sagging Chinese growth is a self-induced problem. Since Xi’s declaration in 2017 that financial stability is a national-security concern, risk-taking by local governments and the financial sector has generally been frowned upon. Because these actors have been the two main engines of China’s growth in the past 10 years, risk-aversion among provincial officials and financiers has naturally sapped energy from the economy.

Yet there is another, under-noticed, source of China’s economic fragility: the capital account of its balance of payments. Since 2014, when China’s foreign reserves began to fall from their US$4 trillion peak (to US$3 trillion today), the authorities have been nervous about the damage excessive capital outflows might inflict on China’s economic self-confidence and global role.

In any emerging economy, there’s an important connection between the health of the capital account and that of the domestic economy. If money is voting with its feet, how can anyone expect domestic confidence to be strong?

Furthermore, the most important single driver of capital flows in and out of any emerging economy is the state of US monetary conditions. Loose US monetary policy in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis pushed capital towards China and other developing countries. That’s what helped reserves grow to US$4 trillion in the first place: the US Federal Reserve’s ‘quantitative easing’ made it profitable for Chinese firms to borrow dollars and sent investors on a global quest for yield, so money flowed to China.

Conversely, the progressive tightening of US monetary conditions over the past five years has undeniably helped to suck dollars away from China, causing the country to lose reserves and self-confidence. This is partly because Chinese companies tend to repay debt when the dollar is strengthening and the cost of servicing dollar liabilities goes up. In addition, foreign portfolio investors are less willing to buy Chinese government bonds when the China–US interest differential narrows, as it has in recent months.

The main reason why reserves haven’t fallen below US$3 trillion, which would make Chinese policymakers even more nervous, is the network of controls on capital outflows introduced in late 2016 and early 2017. But the controls may not be completely watertight: the history of capital flows tells us that when money wants to leave a country, it will.

A fragile capital account, and the economic self-doubt it can create, are hardly strong foundations for aggressive Chinese foreign policy. The next time Trump feels like excoriating Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell for tightening monetary policy too quickly, he might pause to consider the role that higher US rates and a stronger dollar have played in taming China’s self-confidence. A dovish Fed is a gift to Beijing.