Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

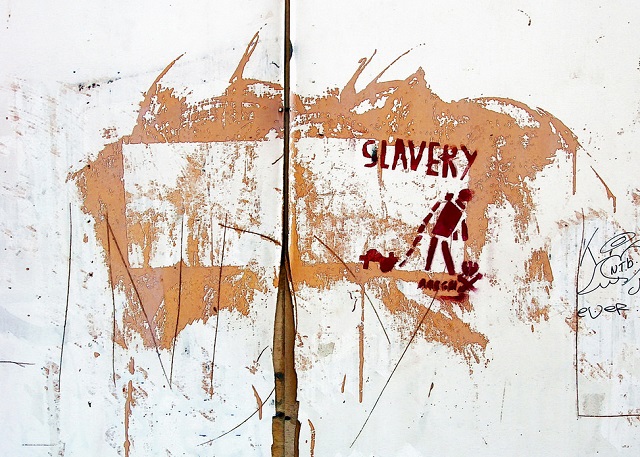

We tend to think of ‘slavery’ as an archaic term. But the fact stands that slavery is still a significant issue in the contemporary world; both in the Asia–Pacific and more locally here in Australia. The problem may be widespread in our region but 2 December 2016—when the United Nations observed the ‘International Day for the Abolition of Slavery’—passed without stimulating much meaningful reflection.

The day marked the adoption of the United Nations Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others in 1949. Since that date, numerous international instruments to prevent slavery have entered into force. Those include the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organised Crime (2003) and its supplementary Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (2003) among others; both of which Australia has ratified.

Australia is known as a destination country for people trafficked from parts of Asia—Thailand, Republic of Korea and Malaysia alike. Australia has recorded instances of human trafficking and other slavery-like practices including servitude, forced labour and forced marriage. Historically, the numbers were made up predominantly by women in the sex industry. But interestingly enough, a shift over the past two years has seen a greater number of victims in the agriculture, construction, hospitality and cleaning industries. But even so—and while statistics grow significantly worse in the region—Australia has actually seen an improvement in the numbers, from an estimated 4,300 living in slavery in 2014 to 3,000 in 2016.

Looking to the Asia–Pacific more broadly, no country is free from the effects of slavery and the numbers are alarming. According to The Global Slavery Index, the region holds a stunning two thirds—approximately 30 million people—of the estimated global 45.8 million enslaved people. Forced labour, child soldiers, forced begging, sexual exploitation and forced marriage were all identified forms of slavery across the region. In absolute terms, China and India have the highest number of people living in slavery. But when considering the estimated percentage of a population in slavery, the biggest culprits in the region are North Korea, Cambodia and India. Worse still, the situation is only deteriorating, with numbers on the rise since 2014 when the estimated number living in slavery in the region was 23 million.

The trends primarily mirror the lack of solutions to address the root of the problem in the region—namely, labour exploitation in supply chains of food production, garment and technology industries. In 2012 the ILO estimated there to be 20.9 million forced labourers globally, with 56% in the Asia–Pacific alone. Those numbers are especially worrying for Australia, given that four of our top five import sources are Asia–Pacific countries; three of which—China, Republic of Korea and Thailand—boast poor track records of slavery

Australian businesses continue to be implicated in labour abuses in-country and abroad, with slave labour occurring in the manufacturing of Australian clothing in North Korea, labour exploitation in Vietnamese, Chinese and Thai fishing industries and labour abuses in domestic fresh food supply chains and 7-Eleven stores. That reflects the need for a broadened approach to anti-slavery that encompasses working with companies, investors and consumers, to complement the existing traditional criminalisation focus.

Remarkably, that was acknowledged at the Sixth Ministerial Conference of the Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Crime earlier this year, which was co-chaired by Australia and Indonesia. Australia’s Foreign Affairs Minister Julie Bishop acknowledged the need to work with the private sector to ‘combat human trafficking and related exploitation, including by promoting and implementing humane, non-abusive labour practices throughout their supply chains.’

Australia’s general response to slavery and human trafficking and National Action Plan to Combat Human Trafficking and Slavery have been commendable and exceptional compared with other regional countries. But it could do more; tangible solutions to the specific issue of supply chain labour exploitation have been delayed.

The Supply Chains Working Group, established under the Attorney-General’s Department in 2014, presented the Australian government with nine recommendations to combat supply chain exploitation in December last year. On 28 November, Australia responded and convened its eighth meeting of the Australian Governments National Roundtable on Human Trafficking and Slavery, announcing that it’ll work with business and civil society to:

That response, already a year delayed, remains vague about committing to any of the Working Group’s recommendations. The only clear cut commitment is to create awareness-raising material, a worthy enough step, but the meatier suggestions are seemingly still just for ‘consideration’ at this point. In comparison, the US and UK have implemented measures requiring businesses with an annual turnover greater than £36 million to report on efforts to eradicate slavery and human trafficking from their direct supply chains.

Australia needs to step up its response and prove commitment to tackling labour supply chain exploitation through timely, tangible solutions. If the short term game is an Australian seat on the Human Rights Council, the longer term game must surely be one where Canberra pursues good international citizenship in order to stamp out slavery and buttress stability in its own backyard and beyond.

UN peacekeepers are often deployed when there’s no longer any peace to keep. In the current strategic environment of non-state actors, peacekeeping has also become increasingly complex and non-traditional in character. Despite those new challenges, we rarely hear about UN peacekeeping operations in Africa, as the news is dominated by the Middle East.

It’s now time for strategic decision makers in the West to appreciate why Africa matters. Of the 16 current PKO missions, nine are on the African continent. Of the roughly 100,000 uniformed peacekeepers currently deployed, 82,000 of them are based in Africa. Those statistics are significant because terrorist organisations—like the so-called Islamic State (IS)—thrive in unstable and insecure environments. Those are the same places that typically require UN peacekeeping operations. That situation will become even more apparent once the IS caliphate is reduced in the Middle East and the group looks elsewhere for safe havens from which to train and launch attacks.

In the future, peacekeepers need to be capable of conducting the full spectrum of peace operations, from humanitarian assistance/disaster relief operations through to missions with a more offensive mandate. For example, the current MINUSMA operation in Mali requires more of a counterinsurgency mindset than a traditional peacekeeping approach. But the problem is that many UN peacekeepers are neither trained nor equipped to deal with evolving threats in the contemporary operating environment.

Of the 100,000 peacekeepers currently deployed, just 39 are Australians. Yet the Australian Defence Force (ADF) has more than 2,300 troops deployed on operations elsewhere around the world. Coalition operations, such as those in Iraq and Afghanistan, are seen to more directly serve Australia’s defence interest of maintaining a rules-based global order. If there was an urgent need for UN intervention in Southeast Asia, however, we’d likely see Australia playing a leading role.

In balancing ways and means to achieve its national security objectives, Australia—as the world’s 12th largest economy—provides more funding than troops for peacekeeping operations. Notably, Australia is the 11th largest financial contributor to the UN peacekeeping budget and the 9th largest donor to the UN peacebuilding fund, which serves to prevent conflict in fragile states. Within our region, the peacebuilding fund is currently supporting peacebuilding projects in Myanmar, PNG, Solomon Islands and Sri Lanka.

Within the UN’s Peacekeeping Capability Readiness System, Australia has pledged the use of C-130 and C-17 aircraft for strategic airlift, capacity building for troop and police contributing countries, and counter-improvised explosive device (CIED) training. At the September 2016 UN Peacekeeping Defence Ministerial Meeting in London, Defence Minister Payne announced additional funding of $1.2 million over five years to further enhance regional UN peacekeeping capacity.

That’s is a noteworthy contribution given Australia’s strategic interests, but Africa deserves more attention. It’s important to Australia for several reasons.

Firstly, Australian companies have billions of dollars invested in Africa—an investment surely worth protecting.

Secondly, just as in the Middle East, we have a moral obligation to protect civilians, particularly women and children in conflict zones. We can’t stand by to allow another Rwanda-like genocide to unfold in Africa. Prevention requires positive action.

Thirdly, the US military has steadily increased its military presence in Africa as a result of growing instability and the rapid expansion of terrorism on the continent. We live in a complex and interconnected world and the terrorism phenomenon is a global threat that will have consequences here if sanctuaries are allowed to exist over there.

UN peacekeeping operations also provide our service men and women with valuable operational experience. I’ve benefited greatly from serving on UN peacekeeping operations in East Timor (UNTAET), Lebanon (UNTSO) and Sudan (UNMIS). UN missions enable a unique and diverse perspective, different from other coalition operations.

Australia can do more. Our service personnel are highly effective trainers who are building partner capacity all over the world. The ADF’s Peace Operations Training Centre (POTC) already trains hundreds of peacekeepers from more than 50 countries every year, but the Centre should be better resourced to increase its rate of effort. POTC should be expanded to become an international centre of excellence for peacekeeping operations.

Additionally, the UN needs to better harness technology in peacekeeping to improve early warning and enhance the ability to detect, deter, mitigate and respond to threats, particularly in an asymmetric environment with non-state actors. Developed countries—like Australia—can contribute more to PKO in the future by providing niche capabilities, like drones, CIED and intelligence sharing.

It’s time we think big picture, look strategically and anticipate future threats. The problems in Africa won’t be fixed overnight. We’re likely to see further atrophy before improvement. As such, terrorist organisations will look to the African continent for opportunities.

From peacekeeping to counterterrorism, Africa matters.

On 12 August, the UN Security Council adopted resolution 2304 authorising the deployment of a further 4,000 troops to the UN peacekeeping mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) as part of a regional protection force. The mandate shift took place amidst recent reports of yet more failures by peacekeepers to come to the aid of civilians. Unfortunately, unlike many UN peacekeeping mandates, the Council wasn’t united in its approach. Russia, China, Venezuela and Egypt all abstained on the resolution. It’s not the first time there have been differences of opinion over the mandate for UNMISS. Yet the growing chasm within the Council comes at a time when UNMISS is being tasked to do even more to secure South Sudan’s capital, Juba, and protect the civilian population.

The latest outbreak of violence in South Sudan erupted in the capital, Juba, just days prior to the five year anniversary of independence for the world’s newest country on 11 July. For most of the population of South Sudan—some 12 million people—there was very little to celebrate anyway. The country has been trying to extricate itself from a violent civil war since December 2013, which has resulted in the displacement of more than 1.6 million civilians internally, forced more than 700,000 to flee across the borders, and resulted in between 160,000 to 200,000 civilians seeking protection at UN sites across the country at any one time. Horrific atrocities and human rights abuses have been inflicted on the civilian population. This has been compounded by an acute humanitarian emergency, with estimates that 4.8 million people are food insecure.

This isn’t the first time that the Security Council has tried to draw South Sudan back from the precipice. Following the outbreak of civil war in December 2013, the Security Council increased the size of the mission and significantly reconfigured it to focus primarily on protection of civilians. Yet the mission continued to limp along in the absence of any political solution to the ongoing conflict until August 2015, when the two major protagonists—President Salva Kiir and the now deposed First Vice-President Riek Machar—eventually signed onto an agreement that would provide a political pathway forward to resolve the largely ethnic-based conflict. The mission mandate was then extensively adjusted again. But not surprisingly, commitment to the agreement wavered from the outset and sporadic fighting continued. That reached boiling point on 7 July 2016 with brutal armed clashes in the capital forcing yet more civilians to flee.

Resolution 2304 is the latest attempt by the Security Council to coerce the Government of South Sudan to resolve the conflict within its borders. However, the UN has been backed into a difficult corner. The political situation is far from conducive to a UN peacekeeping mission. As Aditi Gorur and I note in this report following our visit to South Sudan last year, efforts by UNMISS to move about the country are frequently obstructed by parties to the conflict. Notwithstanding these significant challenges, however, the mission remains the default tool to provide some measure of physical protection for the civilian population. Yet unfortunately even those efforts have been significantly flawed.

Despite protection of civilians being part of the mandate since UNMISS deployed in July 2011, peacekeepers are still failing to respond when civilians come under attack. This has had tragic consequences in South Sudan, not only for the local population but also for foreign aid workers. Adjusting the mandate alone won’t respond to these deficits in the mission. If UNMISS is to be effective when it comes to protecting civilians, then UN personnel need to be held accountable when they fail to intervene. And that message will only be sent if under-performing troop and police contributors are repatriated home when they fail to act.

But this again presents another problem for the mission. It now needs to generate an additional 4,000 military personnel to fulfil the new mission mandate of 17,000 troops. Past experience has shown that will be difficult. When the mission reconfigured in December 2013, efforts to generate an additional 5,500 military personnel were still underway nearly two years later. While recent UN peacekeeping summits have shown that countries are willing to engage, force generation efforts are likely to be compounded by the difficult relationship with the Government of South Sudan, as well as ongoing concerns among contributing countries about the volatile security situation on the ground.

Ultimately a UN peacekeeping mission isn’t the solution to the conflict in South Sudan. Political pressure needs to be brought to bear on the protagonists to fully implement the peace agreement. The arms embargo threatened in resolution 2304 could provide the necessary coercive ‘stick’. But that will require two items in short supply—a degree of political unity in the Council and regional willingness to implement the embargo.

In the absence of any political solution in South Sudan, UN peacekeeping remains the default mechanism to physically protect some of the tens of thousands of civilians seeking a reprieve from the current conflict. Australia is among the more than 60 countries providing uniformed personnel as peacekeepers to UNMISS. And like all those countries, we have an interest in ensuring UNMISS can fulfil its mandate, protect the civilian population and support efforts to find a political resolution to the conflict.

Every September, many of the world’s presidents, prime ministers, and foreign ministers descend on New York City for a few days. They come to mark the start of the annual session of the United Nations General Assembly, to give speeches that tend to receive more attention at home than they do in the hall, and—in the diplomatic equivalent of speed dating—to pack as many meetings as is humanly possible into their schedules.

There is also a tradition of designating a specific issue or problem for special attention, and this year will be no exception. September 19 will be devoted to discussing the plight of refugees (as well as migrants) and what more can and should be done to help them.

It is a good choice, as there are now an estimated 21 million refugees in the world. Originally defined as those who leave their countries because of fear of persecution, refugees now also include those forced to cross borders because of conflict and violence. This number is up sharply from just five years ago, owing primarily to chaos across the Middle East, with Syria alone the source of nearly one in every four refugees in the world today.

The attention of the UN and its member states does not reflect only the increase in numbers or heightened humanitarian concern over the suffering of the men, women, and children who have been forced to leave their homes and their countries. It also stems from the impact of the flow of refugees on destination countries, where it has upended politics in one country after another.

In Europe, the rise of political opposition to German Chancellor Angela Merkel, the Brexit vote, and the growing appeal of nationalist parties on the right can all be attributed to real and imagined fears stemming from refugees. The economic and social burden on countries such as Jordan, Turkey, Lebanon, and Pakistan, all of which are being asked to house large numbers of refugees, is immense. There are also security concerns about whether some of the refugees are actual or potential terrorists.

In principle, there are four ways to do something meaningful about the refugee problem. The first and most fundamental is to take steps to ensure that people need not flee their countries or, if they have, to create conditions that permit them to return home.

But this would require that countries do more to end the fighting in places like Syria. Alas, there is no consensus on what this would require, and even where some agreement exists, sufficient will to commit the required military and economic resources does not. The result is that the number of refugees in the world will grow.

The second way to help refugees is to ensure their safety and wellbeing. Refugees are particularly vulnerable when they are on the move. And after they arrive, many fundamental needs—including health, education, and physical safety—must be met. Here, the challenge for host states is to guarantee adequate provision of essential services.

A third component of any comprehensive approach to refugees involves allocating economic resources to help deal with the burden. The United States and Europe (both European Union member governments and the EU itself) are the largest contributors to the UN High Commission on Refugees, but many other governments are unwilling to commit their fair share. They ought to be named and shamed.

The final aspect of any refugee program involves finding places for them to go. The political reality, though, is that most governments are unwilling to commit to take in any specific number or percentage of the world’s refugees. Again, those who do their fair share (or more) should be singled out for praise—and those who do not for criticism.

All of which brings us back to New York City. Sadly, there is little reason to be optimistic. The 22-page draft ‘outcome document’ to be voted on at the September 19 High Level meeting—long on generalities and principles and short on specifics and policy—would do little, if anything, to improve refugees’ lot. A meeting scheduled for the next day, to be hosted by US President Barack Obama, may accomplish something on the funding side, but little else.

The refugee issue provides yet another glaring example of the gap between what needs to be done to meet a global challenge and what the world is prepared to do. Alas, the same holds true for most such challenges, from terrorism and climate change to weapons proliferation and public health.

We can expect to hear a lot of talk in New York next month about the international community’s responsibility to do more to help existing refugees and address the conditions driving them to flee their homelands. But the cold truth is that there is little ‘community’ at the international level. So long as that remains the case, millions of men, women, and children will face a dangerous present and a future of little prospect.

It’s difficult to keep track of disarmament fora. So readers could be forgiven for overlooking the fact that the UN’s Open-ended Working Group (OEWG) on Taking Forward Multilateral Nuclear Disarmament Negotiations will hold its third meeting in Geneva in mid-August. The group—which has already met during February and May—is a subsidiary body of the UN General Assembly. Its task is to finalise a set of recommendations which ‘substantively address concrete effective legal measures, legal provisions and norms that will need to be concluded to attain and maintain a world without nuclear weapons’. Moreover, the OEWG is also meant to come up with a series of recommendations to facilitate multilateral nuclear disarmament negotiations, including transparency measures, enhancements to nuclear weapon safety and security, and measures to raise awareness of the humanitarian consequences that would result from any nuclear detonation.

That’s no small task. Frankly, nuclear disarmament looks harder now than it did 20 years ago. Much of the first task—some describe it as ‘filling the legal gap’ in the NPT—has turned upon the question of whether the time’s ripe for a treaty banning nuclear weapons. That would be a huge step, made more challenging by the fact that none of the nine current nuclear weapon states seems at all engaged in the UN process. Previously, even when nuclear weapon states have been willing participants, nuclear arms reductions have proved to be fantastically complex exercises. And those negotiations have essentially been bilateral, not multilateral. It’s hard to believe that much progress can be made towards actual nuclear disarmament simply by delegitimising the weapons. Putting it bluntly, we don’t accept the premise underpinning the OEWG’s activity—that what’s essentially a strategic problem can be solved by passing a law against it.

Swirling through the OEWG’s thinking about legal measures—supposedly made ‘concrete’ and ‘effective’ by the enforcement power of the UN Security Council, the permanent five of which are nuclear weapon states—is a strong theme that nuclear weapons are inhuman. Efforts to ban nuclear weapons are founded on the proposition that the humanitarian consequences of their use are intolerable. The campaign is centred on the Humanitarian Pledge movement which Austria initiated in 2014 and pushes for efforts to ‘stigmatise, prohibit and eliminate nuclear weapons’. An UNGA resolution says that they have unacceptable humanitarian consequences because of their ‘immense and uncontrollable destructive capability and indiscriminate nature’.

UNGA voted on the Humanitarian Pledge in July 2015, adopting the resolution with 139 ‘yes’ votes and 29 ‘no’s’, with 17 countries abstaining. Australia voted no, as did Canada, Germany, South Korea and all the P5—except China which abstained, as did Japan and North Korea. Let’s face it, there’s never going to be a majority voting against it. But that doesn’t make Australia’s position wrong. None of the pledgers are nuclear weapon states, nor the beneficiaries of an extended nuclear assurance, so the pledge is merely the strategic equivalent of teetotallers swearing off alcohol.

By what standards do we judge that nuclear weapons are ‘inhuman’? Obviously, the test is rather more than simply one of whether they kill, maim and injure people. All weapons do that. Rather the tests are the classical ones from just war theory. Do the weapons allow for a sense of proportionality? Do they allow for a sense of discrimination between military and civilian targets? Does any sort of use impose unacceptable costs on the broader international community?

The problem is that the answers to those questions depend on how nuclear weapons are used. Most use is, of course, gravitational, not direct: that is, the weapons generate their most helpful effects merely by existing. In direct use, consequences would vary. Obviously, a large warhead dropped on a city would have far greater humanitarian consequences than, say, a tactical nuclear weapon used against a naval target at sea. The first case would be the equivalent of a modern-day Hiroshima; the second an instance of nuclear use in a limited war scenario. True, even the use of a low-yield warhead in an overtly military context would still be ominous—and not least because such use would be freighted with escalation dangers. Still, the actual use might kill no more than a conventional weapon used in the same setting.

Conversely, the fire-bombing of cities in World War 2—Tokyo and Dresden, for example—showed that large numbers of civilians could be killed using conventional weapons. To quote Robert Jervis, the nuclear revolution ‘magnifies in force and compresses in time imperatives that already were present’ in pre-nuclear days. But that magnification and compression ensures nuclear weapons are special and terrible—which is why the mere threat of their use is so effective at inducing caution among decision-makers. Yes, in the long run we should be looking to a world beyond nuclear weapons. But that will take time and effort, not just a vote at the UN.

This past weekend marked the International Day of United Nations Peacekeepers, a day established by the UN General Assembly in 2002 to pay tribute to military, police and civilian peacekeepers and honour those that have lost their lives in the cause of peace.

Australia has an incredibly proud history of deploying personnel to UN peacekeeping operations. Next year will mark 70 years since Australia first deployed personnel under UN auspices to the Dutch East Indies. Since then Australians have served in dozens of UN peacekeeping missions across the globe, in locations ranging from Rwanda to Somalia, and Cambodia to Timor-Leste. ADF and AFP personnel continue that service today in difficult and challenging environments in South Sudan, Liberia, Cyprus and the Middle East.

Yet we remain a small contributor for a country of our size and influence in the global order. Take countries in the G20 as an example. Only two countries deploy less UN peacekeepers than Australia: Mexico, which only recently re-engaged in UN operations, and Saudi Arabia, which deploys none. And Australia’s numbers are set to decline even further. The last contingent of AFP police peacekeepers (currently 10 personnel) serving in Cyprus are set to withdraw by 30 June 2017. That means Australia is likely to have no police deployed to a UN peacekeeping operation for the first time in over 50 years. That’s an unfortunate development when you consider Australia’s leadership in spearheading the first UN Security Council resolution on the role of police in peace operations (2185).

Just over five years ago UN officials suggested that UN peacekeeping was entering a period of consolidation. Yet despite that prediction, the number of peacekeepers has increased again in recent years, with new missions in Mali and the Central African Republic, and an increase in the size of the mission in South Sudan. Although there are expected drawdowns in missions in Liberia, Cote d’Ivoire and Haiti on the horizon, history has shown that there’s often an unexpected need for UN missions. Syria, Libya and Burundi may be among some of the potential candidates for a UN peacekeeping mission in the near future.

In recent years, high-levels of demand for UN peacekeepers created a situation where demand often outstripped supply. The Security Council kept authorising new missions, but the UN couldn’t generate commitments from countries quickly enough to respond. In Mali and the Central African Republic, the UN re-hatted already deployed African Union missions, despite concerns that troop and police contributors didn’t meet performance standards, were known to have questionable human rights records, and often didn’t have the necessary equipment. Consequently, those peacekeeping missions haven’t been as effective as they might have been in implementing their mandates, particularly when it comes to protecting civilians.

Several reforms are underway to improve force generation processes in light of a high-level review last year. However, in order for UN missions have a broader base of capabilities to draw on, it also requires well-equipped and trained countries—such as those previously engaged in NATO operations in Afghanistan—to re-engage in UN peacekeeping. Several of those countries are in the process of stepping up their commitments to UN peacekeeping. The Netherlands and Sweden have deployed personnel and enablers to Mali in substantial numbers. The UK has just started deploying personnel to assist with capacity building in Somalia, and is expected to increase its deployment in South Sudan. And Canada’s Trudeau government is considering options to re-engage more substantively in UN peacekeeping.

Even the US has been utilising its political weight to improve the supply of peacekeeping personnel and capabilities the UN has to choose from. President Obama co-chaired a leaders’ summit on peacekeeping in September 2015. At the summit, more than 50 countries pledged an additional 40,000 troops and police to UN peacekeeping missions. China, Cambodia, Fiji, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia and Thailand were among those countries in our region committing to deploying more personnel.

While Australia didn’t make any commitments to deploy more personnel, the Foreign Minister pledged that Australia would provide training to our regional neighbours and provide strategic airlift ‘where and whenever we can’. However, Australia hasn’t provided any C-17 Globemasters or C-130 Hercules for strategic airlift to UN peacekeeping since January 2014. And there hasn’t been any substantial increase in already established peacekeeping training programs in that time.

In September this year, the United Kingdom will host a follow-on ministerial summit on UN peacekeeping in London. As a country previously making a pledge, Australia will be invited to take part. The event will either present a liability or an opportunity for Australia, depending on the future consideration given to our engagement in the coming months. There’s a real risk that Australia may be perceived as stepping back from this commitment to the global rules-based order at the very moment when our allies, partners and neighbours are heeding the call to step up their operational commitments to UN peacekeeping.

Australia has a proud history of service in UN operations and that should be remembered and commemorated. But we can’t rely on that history to demonstrate our ongoing commitment, nor support our security interests. The government needs to build upon it and give serious consideration to options for Australia’s future engagement as a contributor to UN peacekeeping.

UN Special Envoy for Syria Staffan de Mistura’s background and leadership style (see part 1) have influenced his approach to the Syrian conflict from the day UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon asked him to take on the role. When he got the call in July 2014, de Mistura was enjoying a lovely semi-retirement on the isle of Capri after promising his fiancée and two daughters (from a previous marriage) a ‘more normal life’ after nearly four decades of bouncing between war zones. De Mistura was inclined to say no, but as he tried to sleep that night, he felt guilty. Ban’s words about the numbers of civilians killed and the refugees echoed in his head. He called the Secretary-General back at 3am and accepted the job.

De Mistura initially tried a more bottom-up approach to peacemaking than his predecessors. He took an immediate risk in late 2014 when he proposed a series of ‘freeze zones’ or small, local freezes of violence in the iconic Syrian city of Aleppo. The theory was that the neighbourhood-level freezes could later be linked together and eventually replicated in other cities. While the envoy’s advisors suggested that de Mistura pick a less difficult place, he felt strongly that Aleppo would have symbolic power in demonstrating ‘drops of hope’ and the need to protect civilians elsewhere. De Mistura also hoped that drawing public attention to Aleppo, which was close to collapse, might help prevent the regime or the opposition from escalating the fight.

When both the regime and the opposition ultimately eschewed the Aleppo initiative, Ban instructed de Mistura to try to organise political talks, shifting the envoy back to a more top-down approach to conflict resolution. De Mistura has tried to be more inclusive, acknowledging that the conflict is part of a larger regional contest and shifting geopolitical dynamics. To lay the groundwork for the current talks, he first held one-on-one consultations in Geneva with hundreds of leaders, groups and factions. Shortly thereafter, he logged over 25,000 miles of air travel in two weeks to meet with officials in Syria, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and China.

De Mistura’s forward-leaning style, however, has at times landed him in hot water. The envoy’s critics note that he can sometimes speak too soon and too much, resulting in hyperbole and diplomatic missteps. He offhandedly told reporters in early 2015 that Assad should be part of the solution, sparking intense criticism as it came the same day that the Syrian Government launched missiles and barrel bombs in the city of Douma. De Mistura insists he meant that Assad should be part of the solution for setting up the Aleppo freeze, not part of the solution to the overall Syrian conflict, but his comments further alienated the opposition. De Mistura’s former political director claims that the envoy has at times lost credibility because he tends to tell his interlocutors what they want to hear, and think about the consequences later.

In his efforts to innovate where the status quo has failed, Mistura has relied heavily on small changes in terminology in an attempt to generate big results. He has tried to distinguish the current talks from the high-level summits of his predecessors by calling them the ‘Geneva Intra-Syria talks’ not ‘Geneva III’. His initial Aleppo plan was about ‘freeze zones’ not ‘ceasefires’, which had failed in the past. He referred to his consultations in Geneva as a ‘stress test’, not ‘negotiations’, and he prefers to speak of ‘action plans’, rather than ‘peace plans’. While those terminological nuances might make sense in theory, the media’s disregard for them seems to render his effort ineffective.

As could be expected, de Mistura has come under fire from all sides. The opposition has accused him of favouring the regime, and he has angered the regime with critical public remarks on airstrikes. Political commentators have criticised him for failing to engage the opposition enough, falling victim to manipulation by the regime, and focusing on the political process at the expense of reducing violence against civilians. De Mistura’s own former political director resigned in anger, accusing the envoy of cronyism and incompetence. However, one doesn’t spend 40 years in the UN without developing a thick skin. De Mistura acted quickly to hire a new political director who specialises in constitutional law, and he redoubled his efforts to smooth over relations with opposition leaders. For the most part, he seems undeterred by his critics, saying that complaints are inevitable.

Looking ahead to when the proximity talks resume on 7 March, de Mistura’s efforts may very well continue to sputter or stir up controversy, but it’s hard to blame him for trying and there are still benefits to continuing the conversation. UN expert Richard Gowan explains that maintaining a negotiation process for the sake of it is sometimes an unglamorous necessity. Demonstrating both the value and the risk of talks, he says,

‘UN mediators have kept talks over other intractable conflicts, ranging from Cyprus to Somalia, going for years or decades. It is sometimes necessary to hold consultations to remind everyone that a diplomatic track is still available, although there is a risk that sustaining the process becomes an end in itself.’

Peace and conflict expert Jeni Whalan argues that we mustn’t give up on the Syria talks, highlighting additional advantages:

‘Inconclusive mediation now can still lay essential foundations for a concrete settlement later. Talks allow warring parties to gather new information, reconsider their views of the enemy, and identify potential areas of common ground that can’t be gleaned from battlefield tactics.’

De Mistura himself acknowledges that the talks will be an uphill battle but believes that ‘the time has come to at least try hard to produce an outcome’. In the face of one of the most complex and intractable conflicts of our time, it’s anyone’s guess as to how long his ‘chronic optimism’ will last.

With the world’s attention focused on the ongoing crisis in Syria, it seems odd that Staffan de Mistura, the UN Special Envoy for Syria, has largely flown under the radar. Appointed in July 2014, de Mistura has a seemingly impossible mandate aimed at ‘bringing an end to all violence and human rights violations and promoting a peaceful solution to the Syrian crisis’. As the UN attempts to resume the Geneva Intra-Syrian talks, it’s worth taking a closer look at the man at the heart of the negotiations.

As the Syrian conflict approaches its sixth year, de Mistura faces many of the same challenges that hampered his well-known predecessors, Algerian diplomat Lakhdar Brahimi and former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan. De Mistura must navigate persistent divisions within the UN Security Council, an intransigent Syrian government, a fractured opposition, and increasing militarisation on the ground—obstacles which drove both Brahimi and Annan to resign in frustration. The latest Syria envoy has also inherited a more powerful ISIS, greater military involvement of regional and global powers, and the worst humanitarian crisis of our time. An eternal optimist, de Mistura posits that the worsening conflict and rise of ISIS provide a sense of urgency that can change the parties’ calculus, stating in mid-2015, ‘Sometimes there is a common threat that can produce a common interest in putting aside all the differences in trying to find a constructive solution’.

While de Mistura initially tested a variety of approaches to the Syrian conflict, he has reverted back to the well-worn UN strategy of negotiations held in Geneva. He launched the Geneva Intra-Syrian talks late last month but announced a pause after only a few days of meetings, calling for more work to be done by the mediation team and the stakeholders. De Mistura had hoped to restart talks on 25 February but last week publicly claimed it to be unrealistic. He’s planning to hold six months of on-and-off proximity talks, meaning the delegations sit in separate rooms and UN officials shuttle between them.

At 69 years old, de Mistura isn’t the first person you’d expect to be parachuting into Damascus. The well-heeled dual Italian-Swedish diplomat wears pince-nez glasses and has been known to carry a silver pepper mill with him into the field. Despite his upper-crust proclivities, de Mistura has four decades of experience as a humanitarian officer and troubleshooter in almost 20 conflict zones, including Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Rwanda, Somalia, Sudan and the former Yugoslavia. He speaks an impressive seven languages—English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Swedish and colloquial Arabic.

De Mistura was born in Stockholm to a Swedish aristocrat mother and an Italian marquis father who was exiled from the Dalmatia region in the Adriatic after World War II. He grew up in Rome where he attended an elite, Jesuit-run high school and earned a degree in political science and development economics from the University of Rome.

The envoy’s rise to the head of the Syria negotiation table is the result of a lengthy and distinguished career, which began at the UN way back in 1971. De Mistura led the UN’s missions in Afghanistan (2010–11) and Iraq (2007–09), garnering particular praise for his work facilitating Iraq’s provincial elections in 2009. His diverse resume also includes stints as the Executive Director of the UN Staff System College in Turin (2006–07), Personal Representative in southern Lebanon (2000–04), and Director of the UN Information Centre in Rome (1997–99). Earlier in his career, de Mistura served at UNICEF, the World Food Programme (WFP) and the Food and Agricultural Organization.

While on a brief hiatus from the UN to serve as Italy’s deputy foreign minister (2011–13), de Mistura led negotiations related to a dispute with India. In May 2014 he was appointed President of the Board of Governors for the European Institute of Peace, and he’s also Sweden’s consul to the exclusive Italian island of Capri.

De Mistura’s appreciation for the UN and his dedication to helping refugees, internally displaced persons and migrants stem in part from his father’s experience as a stateless refugee. He told a reporter in 2006:

‘I became passionate about what the UN stands for because I believed in what my father told me that there has to be a different way of looking at the world than the one we saw in the war, the nations must have a united vision in an organization such as the UN…there must be a UN.’

While working as a student intern for the WFP in Cyprus, de Mistura witnessed the death of a boy by sniper fire, a turning point that inspired his career at the UN. He explains, ‘Ever since this incident I became motivated as a young adult by a sense of constructive outrage, something that influenced me to study humanitarian emergency relief in university to dedicate my life for this kind of work’. He says he continues to be motivated by the dignity and courage of the civilian victims he has met throughout his career.

Despite first impressions of de Mistura’s ‘aristocratic glamour ’—he wears finely cut suits and kisses hands—political commentators describe the envoy as businesslike, an attentive listener, and sincere in his care for civilians. A self-described ‘operational diplomat’, de Mistura claims to be ‘obsessed with results’ because he has seen firsthand the impact he can make in improving people’s lives if he works hard enough.

De Mistura often relies on optimism, innovation and a willingness to take risks—an unusual trait in the diplomatic community. He refers to himself as a ‘chronic optimist’ and has publicly quoted the playwright Samuel Beckett: ‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail better’. A reporter from The Guardian explains how he established a reputation for creativity:

‘Colleagues and friends regaled me with tales of his talent for improvisation: how he convinced a commercial airline to fly food into a starving Kabul in 1989; how he had World Food Programme camels carrying vaccines in Sudan painted blue so they could be spotted by helicopters and protected against theft; how he used smugglers to break the siege of Sarajevo and bring meals and blankets to the city’s desperate inhabitants.’

In Syria, however, de Mistura soon discovered how quickly his forward-leaning, inventive and independent-minded approaches could land him in hot water. Part 2 will address de Mistura’s approach to the Syrian conflict.

The half-way mark in a marathon is always a testy time. So too is the mid-way point of the Paris climate negotiations.

The speeches by 150 heads of state on the opening day of the conference were intended to inject some early momentum into the negotiations. Yet as soon as the formal negotiations began, the parties climbed back into their well-worn trenches and progress became painfully slow.

The plan, and hope, was that the negotiators would whittle down the hefty draft text of the ‘Paris Agreement’ into a shorter and relatively cleaner text for the ministers to finalise by the end of the second week.

By Saturday—the handover date—the text was only a little shorter and not much cleaner. Many sections were a jumble of bracketed text and alternative options that reflect deep disagreement among many parties and negotiating blocs.

It’s also been a struggle for everyone to follow the negotiations in the first week. There are around 20,000 official delegates and 10,000 accredited observers secured inside the Le Bourget conference site. All but the plenary sessions have been closed to observers. Even parties with large delegations have found it difficult to stay abreast, with up to 150 sets of negotiations (including spin off groups and bilateral and informal negotiations) taking place at any one time.

Nonetheless, the hot button issues are plain to see. Those include the temperature target and the long-term goal of the agreement, the review mechanism, transparency and accountability, and above all, the crucial cross-cutting issues of differentiation and climate finance.

The most vulnerable parties are desperately fighting for a temperature target of no more than 1.5 degrees. That’s resisted by many major economies and especially Saudi Arabia.

There’s no consensus yet on whether the long-term goal should be decarbonisation (rejected by fossil fuel states), zero global emissions, net zero global emissions, carbon neutrality or a long-term low emissions transformation—to name only some of the bracketed options.

Nor is it clear whether a specific date or time period for achieving this long-term goal can be agreed. Options include 2050, 2060–80, end of the century, or as soon as possible after mid-century.

The review mechanism debate revolves around whether and how the 188 ‘intended nationally determined contributions’ (INDCs) that have been submitted by the parties for the post-2020 period should be reviewed, and whether subsequent contributions in the ongoing cycles of commitment must represent forward progression or simply just not go backwards. The latter would fail to generate the dynamism to drive a rapid ratcheting-up of ambition to hold warming to below two degrees (let alone 1.5 degrees).

The key division in the debate over transparency in mitigation action and support turns on how much flexibility should be accorded to developing and least developed countries. The US and EU want the transparency and accountability rules to apply to all parties while many developing countries reject a one-size-fits-all approach.

Cutting across and infusing all of these debates are the crucial issues of differentiation and climate finance.

Developing countries have continued to point out that developed countries haven’t fulfilled their obligation to lead in mitigation under the 1992 Convention or to provide adequate finance and other support to developing countries, which was promised in the Copenhagen Accord in 2009.

In response, many developed countries point out that the world has change since 1992 and the old binary between developed and developing countries, as reflected in the annexes to the 1992 Convention, are now well and truly outdated.

As a consequence, the draft language on finance is a sea of brackets and the multiple references to differentiation throughout the text are heavily bracketed.

The US and China have made it clear that they are strongly committed to reaching a deal. However, there are 194 other parties that must also consent to this agreement.

The problem is that the hyper-flexible approach favoured by the G2 doesn’t provide the more climate vulnerable parties with the assurances they need to ensure their continuing existence. Saudi Arabia has also been playing its usual blocking game by rejecting proposals designed to strengthen climate protection.

Sorting out these and many other differences will require major compromises. A commitment to scale up climate finance and other support (technology transfer and capacity building) by developed countries (and possibly some major developing countries) will certainly help to unlock many, if not all, of these differences.

Without this support, many developed countries won’t have the means to pursue a clean energy pathway and adapt to the warming that’s already locked in. They also argue that they are entitled to this support given their pressing development needs and the fact that many in this large and diverse bloc are the least responsible for emissions and the least capable of adapting to a dangerously warmer world.

The irony is that the lower the ambition and dynamism of the Paris agreement, the greater pressure major donor countries will face to scale up climate finance and other support to vulnerable countries for mitigation, adaptation and, increasingly, unavoidable loss and damage. If they don’t pay now, they’ll be called upon to pay a great deal more as time goes by.

The French President of the conference, Laurent Fabius, has made it clear that he is committed to an orderly process of negotiations that respects the rules of procedure to avoid any derailments of the kind that plagued the Copenhagen negotiations.

The negotiations in the second week of COP21 will be conducted in a single setting to ensure transparency for parties and observers, with smaller group negotiations over contentious issues reporting back on a regular basis.

The conference President and his diplomatic team will have to draw on all of their skills and political capital, along with a little bit of wizardry, to orchestrate an acceptable text at the end of the week if an agreement is to be adopted by all 196 parties in the closing plenary.

Will the Paris climate change conference measure up?

The answer to that question, of course, depends on what success is measured against. And it’s important that we not only have a clear idea of the short term objectives but, more importantly, where the Paris COP (Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) meeting sits as part of longer-term global efforts to control climate change. Failure to understand these goals can paint a misguided picture of the desired outcomes.

The 2009 Copenhagen COP meeting is a case in point. Expectations for that meeting were extraordinarily high. Many expected the Copenhagen meeting to produce legally binding targets that would get emissions under control and pave the way to stabilising the climate system. When those goals weren’t met, the meeting was uniformly reported as a failure by the media and by environmental groups around the world.

But in retrospect, the Copenhagen COP meeting was a considerable success. First, despite unprecedented attempts to undermine the scientific understanding of human-caused climate change, the assembled politicians at the Copenhagen COP accepted the scientific evidence that humans are causing climate change, as assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Second, the meeting agreed to limit human-caused climate change to a maximum rise of 2oC in global average temperature compared to the pre-industrial baseline. That has now been reaffirmed and is well established as the global climate policy target.

The Copenhagen COP was also important because state leaders, prime ministers and presidents participated. This clearly elevated climate change from being ‘just’ an environmental problem to being a complex social, economic and environmental challenge that threatens the wellbeing of all humans on Earth.

So the Copenhagen COP was a landmark meeting that achieved several important milestones in meeting the challenges of climate change.

By contrast, the Paris COP meeting is already a success even before being held. The preparatory work has been outstanding and the results impressive.

Importantly, expectations of the outcome have been much better managed this time around. There’s no expectation that the Paris meeting is the ‘be-all and end-all’ of climate negotiations, nor do we expect a legally-binding agreement. In fact, it would likely be counterproductive if a legally-binding agreement emerged.

And for the first time, countries will turn up to a COP meeting with their emission reduction targets already on the table. That will avoid the sort of wrangling we saw in Copenhagen over precise details of targets and timetables. More importantly, we now have a clear picture of where we stand as a global community.

The result of this synthesis is interesting. If all countries meet their Paris commitments, the world is headed for something around a 3oC temperature rise by 2100 compared to the pre-industrial baseline. That’s still too high, but the critical point is that the ambitions of countries, especially the big emitters like the US and China, have been increasing with time.

That’s why a legally-binding agreement is not so important. The climate policy landscape is fluid and dynamic, generally moving in a positive direction as countries understand that rapid technological developments, such as renewable energy systems, are making solutions more feasible than they appeared just five years ago. And that’s why we don’t want to lock interim targets into an agreed legal framework.

With the Paris COP already a success, how should we measure the positive outcomes and progress from the meetings?

First, the conference could achieve a framework for accommodating the fluid nature of climate pledges. Such a mechanism could perhaps take the form of a formal review and re-commit process at five-year intervals. That would allow countries to increase their ambitions as low-carbon technology advances further, along with other solutions, and as the risks of climate change are better known.

Second, the Paris conference needs to make progress on the funding and operation of the so-called ‘Green Climate Fund’. That instrument aims to provide financial support to the world’s poorer countries to help them adapt to the unavoidable impacts of climate change, which preferentially hit the world’s least developed countries. It also provides the means for poorer countries to develop along low-carbon pathways rather than follow the historical, fossil fuel-driven pathway of the industrialised world.

Implementing the Green Climate Fund is complex, and much work needs to be done before it’s operational. The Paris COP meeting won’t solve all of the contentious issues around the Fund, nor should it be expected to do so. But substantial progress towards resolving the thorny issues as well as a clear pathway for further progress on the Fund would be an outstanding outcome for the Paris conference

Significant challenges will remain after Paris. One such challenge is moving from the current targets-and-timetables approach for measuring ambition to the more scientifically sound approach of carbon budgeting. Developing detailed pathways for achieving the promised emission reductions is another.

The careful preparation that has gone into the Paris COP has already made it a success. Further progress in Paris will cement its legacy as a key milestone along the long and winding road to stabilising the climate system.