Social media as it should be

Mathematician Cathy O’Neil once said that an algorithm is nothing more than someone’s opinion embedded in code. When we speak of the algorithms that power Facebook, X, TikTok, YouTube or Google Search, we are really talking about choices made by their owners about what information we, as users, should see. In these cases, algorithm is just a fancy name for an editorial line. Each outlet has a process of sourcing, filtering and ranking information that is structurally identical to the editorial work carried out in media—except that it is largely automated.

This automated editorial process, far more than its analogue counterpart, is concentrated in the hands of billionaires and monopolies. Moreover, it has contributed to a well-documented list of social ills, including large-scale disinformation, political polarisation and extremism, negative mental-health impacts and the defunding of journalism. Worse, social-media moguls are now doubling down, seizing the opportunity of a regulation-free operating environment under Donald Trump to roll back content-moderation programs.

But regulation alone is not enough, as Europe has discovered. If our traditional media landscape featured only a couple of outlets that each flouted the public interest, we would not think twice about using every available tool to foster media pluralism. There is no reason to accept in social media and search what we would not tolerate in legacy media.

Fortunately, alternatives are emerging. Bluesky, a younger social-media platform that recently surpassed 26 million users, was built for pluralism: anyone can create a feed based on any algorithm they choose, and anyone can subscribe to it. For users, this opens many different windows onto the world, and people can also choose their sources of content moderation to fit their preferences. Bluesky does not use your data to profile you for advertisers, and if you decide you no longer like the platform, you can move your data and followers to another provider without any disruption.

Bluesky’s potential does not stop there. The product is based on an open protocol, which means anyone can build on top of the underlying technology to create their own feeds or even entirely new social applications. While Bluesky created a Twitter-like microblogging app on this protocol, the same infrastructure can be used to run alternatives to Instagram or TikTok, or to create totally novel services—all without users having to create new accounts.

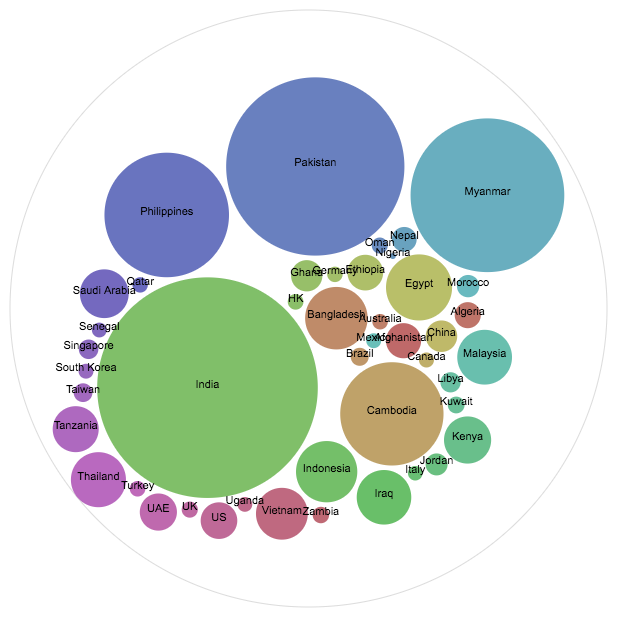

In this emerging digital world, known as the Atmosphere, so named for the underlying AT Protocol), people have begun creating social apps for everything from recipe sharing and book reviews to long-form blogging. And owing to the diversity of feeds and tools that enable communities or third parties to collaborate on content moderation, it will be much harder for harassment and disinformation campaigns to gain traction.

One can compare an open protocol to public roads and related infrastructure. They follow certain parameters but permit a great variety of creative uses. The road network can convey freight or tourists, and be used by cars, buses, or trucks. We might decide collectively to give more of it to public transportation and it generally requires only minimal adjustments to accommodate electric cars, bikes and even vehicles that had not been invented when most of it was built, such as electric scooters.

An open protocol that is operated as public infrastructure has comparable properties: our feeds are free to encompass any number of topics, reflecting any number of opinions. We can tap into social-media channels specialised for knitting, bird watching or book piles, or for more general news consumption. We can decide how our posts may or may not be used to train AI models, and we can ensure that the protocol is collectively governed, rather than being at the mercy of some billionaire’s dictatorial whims. Nobody wants to drive on a road where the fast lane is reserved for cybertrucks and the far right.

Open social media, as it is known, provides the opportunity to realise the internet’s original promise: user agency, not billionaire control. It is also a key component of national security. Many countries are now grappling with the reality that their critical digital infrastructure—social, search, commerce, advertising, browsers, operating systems and more—is subordinated to foreign, increasingly hostile, companies.

But even open protocols can become subject to corporate capture and manipulation. Bluesky itself will certainly have to contend with the usual forms of pressure from venture capitalists. As its CTO, Paul Frazee, points out, every profit-driven social-media company ‘is a future adversary’ of its own users, since it will come under pressure to prioritise profits over users’ welfare. ‘That’s why we did this whole thing, so other apps could replace us if/when it happens.’

Infrastructure may be privately provided, but it can be properly governed only by its stakeholders: openly and democratically. For this reason, we must all set our minds on building institutions that can govern a new, truly social digital infrastructure. That is why I have joined other technology and governance experts to launch the Atlas Project, a foundation whose mission is to establish open, independent social-media governance and to foster a rich ecosystem of new applications on top of the shared AT Protocol. Our goal is to become a countervailing force that can durably support social media operated in the public interest. Our launch is accompanied by the release of an open letter signed by high-profile Bluesky users such as the actor Mark Ruffalo and renowned figures in technology and academia such as Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales and Shoshana Zuboff.

There is nothing esoteric about our digital predicaments. Despite the technology industry’s claims, social media is media, and it should be held to the same standards we expect from traditional outlets. Digital infrastructure is infrastructure, and it should be governed in the public interest.