France is prominent in efforts to shape Syria’s future, again

As Syria and international partners negotiate the country’s future, France has sought to be a convening power. While France has a history of influence in the Middle East, it will have to balance competing Syrian and international interests.

After the fall of Damascus on 8 December 2024, Paris moved rapidly to personalise ties with factions in Syria that it wants to see accepted and engaged in Syria’s national reunification and reconstruction.

On 11 December, French Foreign Minister Jean-Noel Barrot held talks outside Syria with the Syrian Negotiation Commission. The commission was set up in 2015 by Syrian opponents to Bashar al-Assad’s regime and was recognised by the United Nations as the official opposition and responsible for negotiating a political resolution in Syria, but it has since been largely sidelined.

On 17 December Paris followed up with a diplomatic mission to Damascus to meet the real figures of power in Syria: senior Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) leaders, notably former al-Qaeda operative and jihadist Abu Mohammed al-Jawlani, president of the interim government, who now goes by the name of Ahmed al-Sharaa. This French delegation was the first in 12 years to visit Syria.

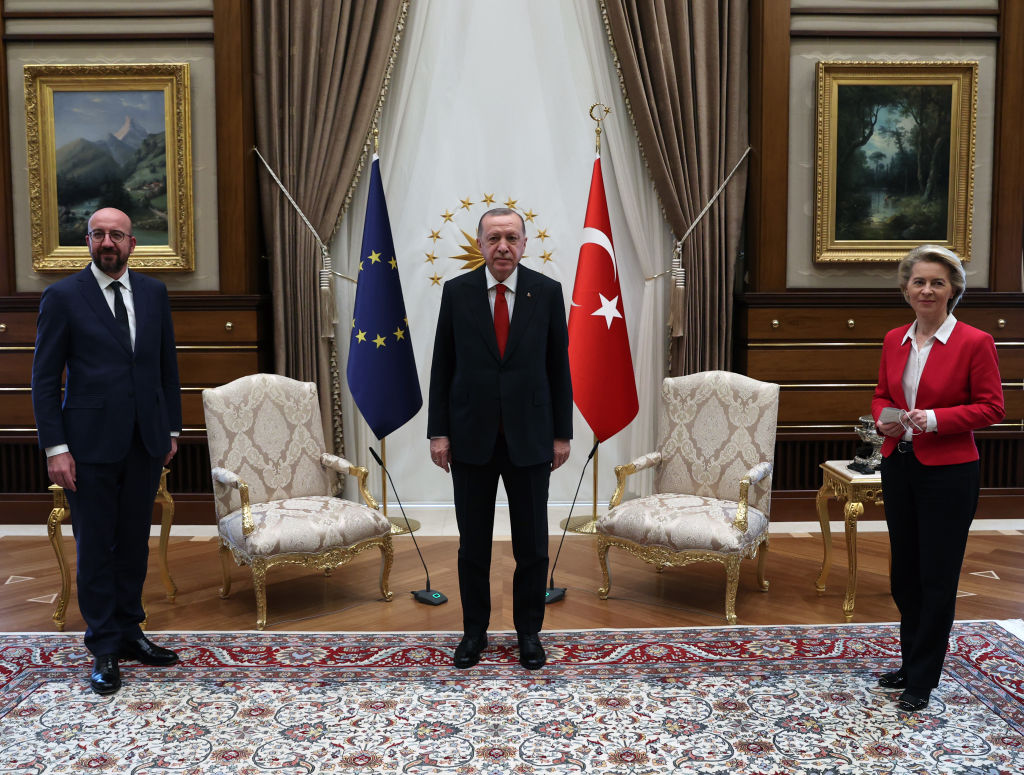

Then on 13 February France convened an international conference to discuss Syria’s situation and outlook. Representatives of 20 countries, the European Union, the UN, the Arab League and the Gulf Cooperation Council attended.

Previously, France sought to shape the situation in Syria through its firm support through UN General Assembly Resolution A/71/248 for the 2016 creation of the International Impartial and Independent Mechanism. This mechanism supports justice by collecting evidence of war crimes and during the Syrian civil war was assisted by 28 Syrian civil-society organisations. It has been supported by funding from the UN and 32 countries.

France’s interest in the Levant dates back to its historical competition with Britain over access to the Red Sea through the Suez Canal and overland trade from Antakya on today’s Turkish coast to Baghdad, Basra and the Indian Ocean. France tussled with Britain over the status of Antakya until Turkey annexed the region in 1939, generating a flight of Christians and local Alawites into Syria.

France also considers protection of Christians as part of its residual influence in the region. This is especially true in Lebanon, but francophone Christianity extends into Syria and remains a social and economic current with subsurface political links.

So, Paris convening of the 13 February summit is no surprise, as there’s currently no other high-level international activity on Syria other than by the UN Security Council.

But with several countries and international groups pushing their interests in Syria, France faces an uphill battle to set the agenda.

EU states are concerned that the potential loss of Kurdish control of foreign-funded camps housing thousands of Islamic State (ISIS) adherents may allow detainees to walk free and spread their destructive ideology across Europe and the Middle East. There are 800 Swedish citizens in detention as ISIS supporters, 6000 ISIS family members from 51 countries in al-Hol camp and 10,000 ISIS combatants in 28 prisons in northeast Syria.

Such detainment centres are controlled by the US-backed Syrian Defence Force, so the EU can’t suppress ISIS without full cooperation, if not leadership, from Washington.

The EU has some ability to influence the Syrian interim government led by al-Sharaa. The EU can use its sanctions-lifting power and aid delivery as tools to shape Syria’s approach to governance and the facilitate the return of Syrian refugees. Given the opportunities available in Europe and continuing instability in Syria, few Syrian refugees will rush to return. So, the EU must not lift sanctions without a significant deal with the new government.

Turkey wants to limit Kurdish organisations and military formations. Skirmishes continue between Ankara and the largely Kurdish Syrian Defence Force. Ankara sees the force as a cover for the Kurdistan Workers Party, which the EU, Turkey and the US consider a terrorist organisation. Limiting Kurdish power would grant Turkey full control along and inside Syria’s northern border. Al-Sharaa has agreed with Turkey, his major backer, that Kurdish separatism has no place in the new HTS-run Syria.

The United States supports Kurdish forces, whom it pays to keep ISIS-linked families and others in camps and to control captured Syrian territory. US bases such as al-Tanf in eastern Syria have acted as tripwires against Iranian efforts to supply weapons to Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon. But US President Donald Trump may withdraw US troops. This would reduce US influence, strengthening Turkey’s position.

Religion plays a deep and unavoidable role in Syria. The EU has partially linked sanctions relief to al-Sharaa’s promise of freedom of worship for minority religions. The EU has also promoted the importance of women’s rights, freedom of expression and due legal process. Delayed lifting of sanctions and aid delivery threaten domestic upset, so HTS is under pressure to meet Western expectations.

Lifting sanctions too quickly may disincentivise HTS from maintaining engagement with international partners and instead allow it to suppress religious expression, squash political debate, shut down human rights organisations and reduce regime transparency.

However, Washington’s early easing of sanctions against certain HTS leaders made diplomatic talks possible.

It’s clear that few Syrian representatives reflect the kaleidoscope of interests in the country. The Turkish-backed National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces, a cluster of players who aimed to rid Syria of Assad, is no longer visible; nor are its members. Turkey may back the new HTS regime at the cost of dialogue and the risk of reigniting civil war.