The great chips war

In addition to dealing with the fallout from open warfare in eastern Europe, the world is witnessing the start of a full-scale economic war between the United States and China over technology. This conflict will be highly consequential and it is escalating rapidly. Earlier this month, the US Commerce Department introduced severe new restrictions on the sale of advanced semiconductors and other US high-tech goods to China. While Russia has used missiles to try to cripple Ukraine’s energy and heating infrastructure, the US is now using export restrictions to curtail China’s military, intelligence and security services.

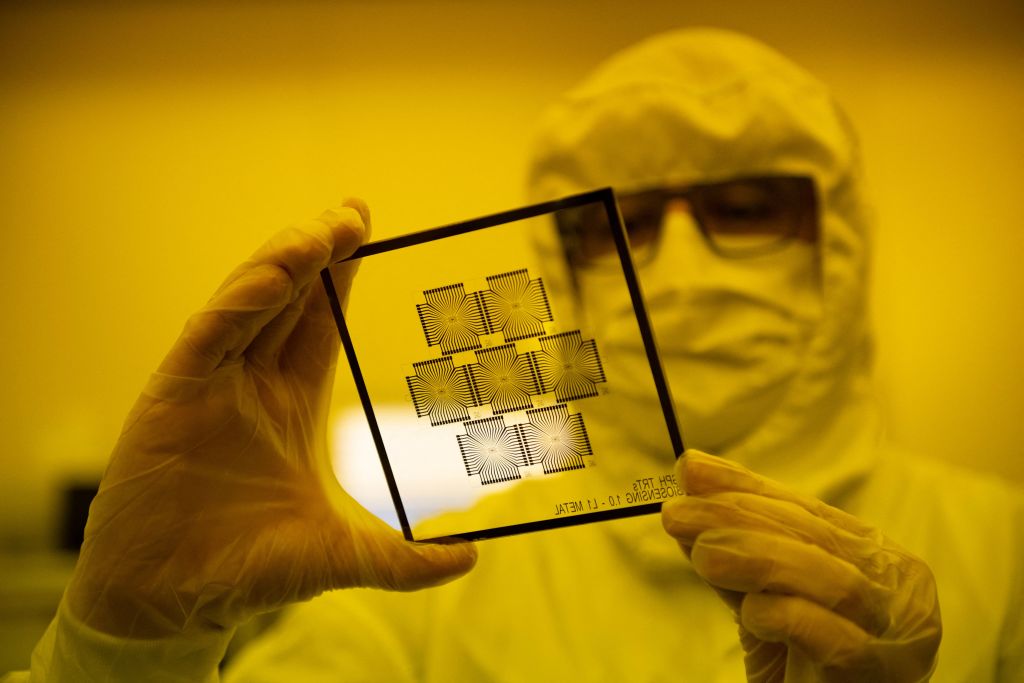

In late August, US President Joe Biden signed the CHIPS Act, which includes subsidies and other measures to bolster America’s domestic semiconductor industry. Semiconductors are, and will remain, at the heart of the 21st-century economy. Without microchips, our smartphones would be dumb phones, our cars wouldn’t move, our communications networks wouldn’t function, any form of automation would be unthinkable, and the new era of artificial intelligence that we are entering would remain the stuff of sci-fi novels. Controlling the design, fabrication and value chains that produce these increasingly important components of our lives is thus of the utmost importance. The new chip war is a war for control of the future.

The semiconductor value chain is hyper-globalised, but the US and its closest allies control all the key nodes. Chip design is heavily concentrated in America, production would not be possible without advanced equipment from Europe, and fabrication of the most advanced chips—including those that are critical for AI—is located exclusively in East Asia. The most important player by far is Taiwan, but South Korea is also in the picture.

In its own pursuit of technological supremacy, China has become increasingly reliant on these chips, and its government has been at pains to boost domestic production and achieve ‘self-sufficiency’. In recent years, China has invested massively to build up its own semiconductor design and manufacturing capabilities. But while there has been some progress, it remains years behind the US, and, crucially, the most advanced chips are still beyond China’s reach.

It has now been two years since the US banned all sales of advanced chips to the Chinese telecom giant Huawei, which was China’s global technology flagship at the time. The results have been dramatic. After losing 80% of its global market share for smartphones, Huawei was left with no choice but to sell off its smartphone unit, Honor, and reorient its corporate mission. With its latest move, the US is now aiming to do to all of China what it did to Huawei.

This dramatic escalation of the technology war is bound to have equally dramatic economic and political consequences, some of which will be evident immediately and some of which will take some time to materialise. China most likely has stocked up on chips and is already working to create sophisticated new networks to circumvent the sanctions. (After Huawei spun it off in late 2020, Honor quickly staged a comeback, selling phones that use chips from the US multinational Qualcomm.)

Still, the new sanctions are so broad that, over time, they will almost certainly strike a heavy blow not only to China’s high-tech sector but also to many other parts of its economy. Any European company that exports to China now must be doubly sure that its products contain no US-connected chips. And, owing to the global nature of the value chain, many chips from Taiwan or South Korea also will be off-limits.

The official aim of the US policy is to keep advanced chips out of the Chinese military’s hands. But the real effect will be to curtail China’s development in the sectors that will be critical to national power in the decades ahead. China will certainly respond with even stronger efforts to develop its own capabilities. But even under the best circumstances, and despite all the resources it will throw at the problem, any additional efforts will take time to bear fruit, especially now that US restrictions are depriving China of inputs that it needs to achieve self-sufficiency.

The new chips war eliminates any remaining doubt that we are witnessing a broader Sino-American decoupling. That development will have far-reaching implications—only some of them foreseeable—for the rest of the global economy.

Ukraine is already repairing and restarting the power stations that have been hit by Russian missile barrages since the invasion began in February. But it will be much more difficult for China to overcome the loss of key technologies. As frightening as Russia’s 20th-century-style war is, the real sources of power in the 21st century do not lie in territorial conquest. The most powerful countries will be those that master the economic, technological and diplomatic domains.