Summing up the Biden–Xi summit

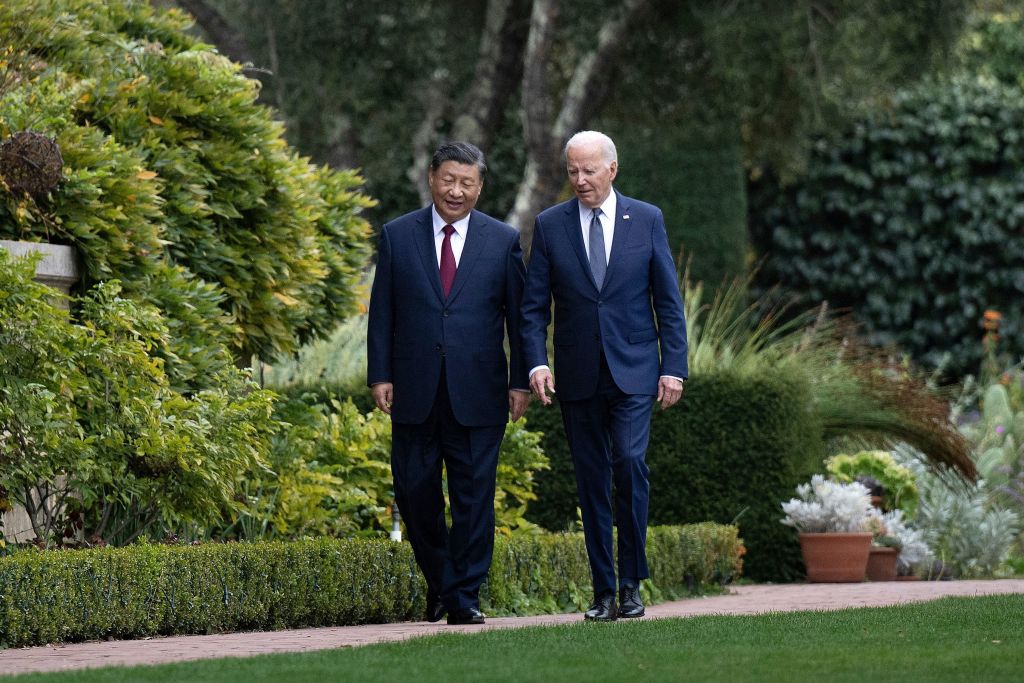

Summits are by definition occasions of high politics and drama, so it comes as little surprise that the 15 November meeting between US President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping generated immense global interest. It was a useful meeting: Biden and Xi agreed to restart military-to-military communications, curb the deadly opioid fentanyl, fight climate change and discuss risks associated with artificial intelligence. But it was also something less than a reset of a relationship that has been deteriorating for several years and that will remain typified by competition more than anything else for the foreseeable future.

Both leaders came to San Francisco hoping the four-hour meeting (held alongside the APEC forum) would place a floor (to use Biden’s favourite image) under what is the defining bilateral relationship of this era. But it’s worth noting that their motives differed fundamentally. Biden wanted to reduce tensions, since the last thing he needs is another diplomatic or, worse, military crisis at a time when an overstretched United States is contending with Russian aggression against Ukraine in Europe and the after-effects of Hamas’s 7 October terrorist attack in Israel.

Biden, a year away from the 2024 presidential election, also needed to show he could be tough on China, both to parry Republican attacks and to show that he was focused on issues that are touching American lives. In this regard, he successfully pushed China to pledge to do more to rein in its exports of the chemical precursors that cartels in Mexico use to manufacture fentanyl.

Xi, for his part, came to California somewhat weakened, owing to the Chinese economy’s underperformance. Following years of excessive state intervention since Xi came to power a decade ago, youth unemployment is high, exports and foreign direct investment are down, and debt is a major issue. The last thing Xi and China’s economy need are more US export controls, sanctions and tariffs.

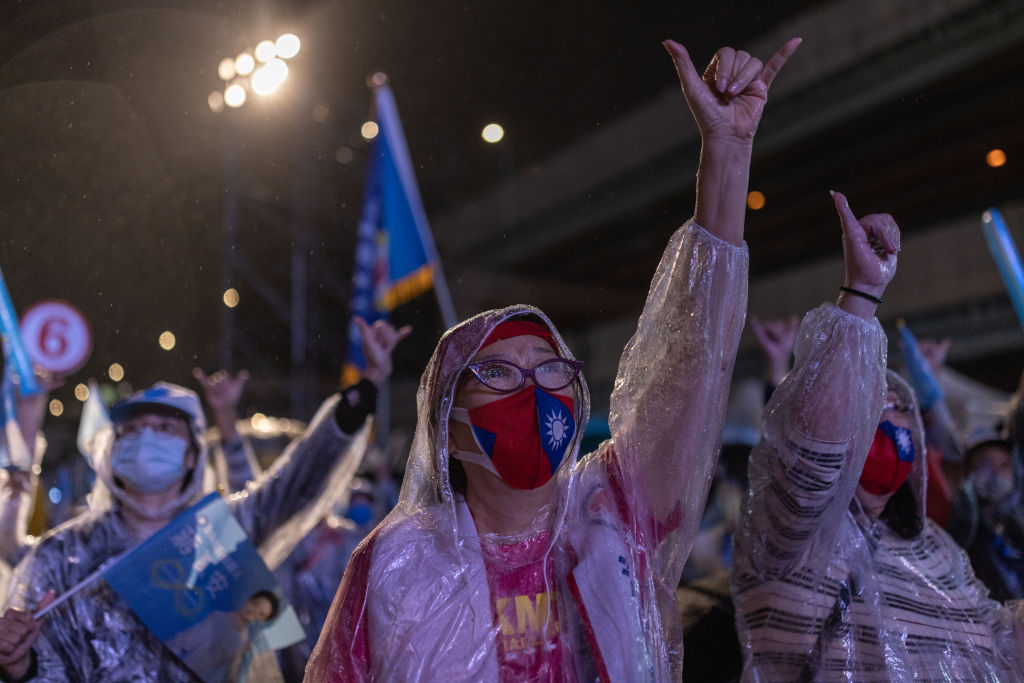

What did not change as a result of the conversation was the status of the most contentious issue dividing the US and China: Taiwan. For the past half-century the two governments have finessed the issue, essentially agreeing to disagree over the ultimate relationship between the island and the People’s Republic. Xi sees unification as central to his country’s future and to his own legacy; the US sees protecting Taiwan from coercion as central to America’s standing with its allies in the region and the fate of a rules-based international order. It’s likely that tensions stemming from these contrasting agendas will periodically spike in the future as in the past.

One piece of good news in this context was the agreement to re-establish military-to-military communications, which China cut off in the wake of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s trip to Taiwan in August 2022. This is welcome in principle because it reduces the chances of an incident involving US and Chinese aircraft or ships, which operate in close proximity to one another on a daily basis. But whether this channel could be relied upon if an incident occurred, and, if so, to what effect, remains an open question.

The summit appeared to produce the promise of enhanced US–China cooperation on climate change and on regulating the use of AI. What will matter, though, is whether the spirit of that promise ultimately translates into meaningful concrete action.

The summit didn’t appear to bridge Chinese and American differences over the world’s two major ongoing conflicts. China is very much in Russia’s corner, while the US is in Ukraine’s, and China (unlike the US) has distanced itself from Israel in the wake of the 7 October attack, refusing to condemn Hamas and calling for an unconditional ceasefire.

Despite these differences, the two governments don’t appear to be on a collision course in either region. China has held off on arming Russia, and it has a stake in not seeing conflict in the Middle East escalate to a point that jeopardises its ability to import Iranian oil. Xi also wants to avoid a scenario where mounting geopolitical differences over either of these crises provide a pretext for the US to take additional steps that would add to China’s economic difficulties.

But it remains to be seen whether such calculations on Xi’s part will lead China to exercise restraint in the South China Sea, where it has been applying increasing pressure against the Philippines, a long-standing American ally. And the summit provided no reason to believe that China is prepared to use its influence to rein in the nuclear and missile programs of North Korea.

Over seven decades, the modern US–China relationship has evolved significantly. Early on, there was no relationship to speak of, and the US found itself in an armed confrontation with China during the Korean War. That was followed two decades later by a period of strategic cooperation against the Soviet Union, and then to boost trade and investment as a joint priority once the Cold War ended. But economic ties have become a source of friction in recent years, and as China became increasingly assertive, the two countries found themselves increasingly at odds over just about everything, from regional and global issues to human rights.

The San Francisco summit didn’t alter this reality. US–China relations remain an issue to be managed, not a problem to be solved. Expecting anything else from the summit was to expect too much. The world’s most important bilateral relationship continues to be a highly competitive one, and the challenge remains what it was prior to the summit: to ensure that competition doesn’t preclude selective cooperation or give way to conflict.