Editors’ picks for 2024: ‘Submarine agency chief: Australia’s SSNs will be bigger, better, faster’

Originally published on 28 May 2024.

The nuclear-powered, conventionally armed submarines to be built under the AUKUS agreement are on track to be the world’s most advanced fighting machines, says Australian Submarine Agency Director-General Jonathan Mead.

‘They’ll have greater firepower, a more powerful reactor, more capability and they’ll be able to do more bespoke operations, including intelligence gathering, surveillance, strike warfare, special forces missions and dispatching uncrewed vessels, than our current in-service submarines,’ Vice Admiral Mead says in an interview.

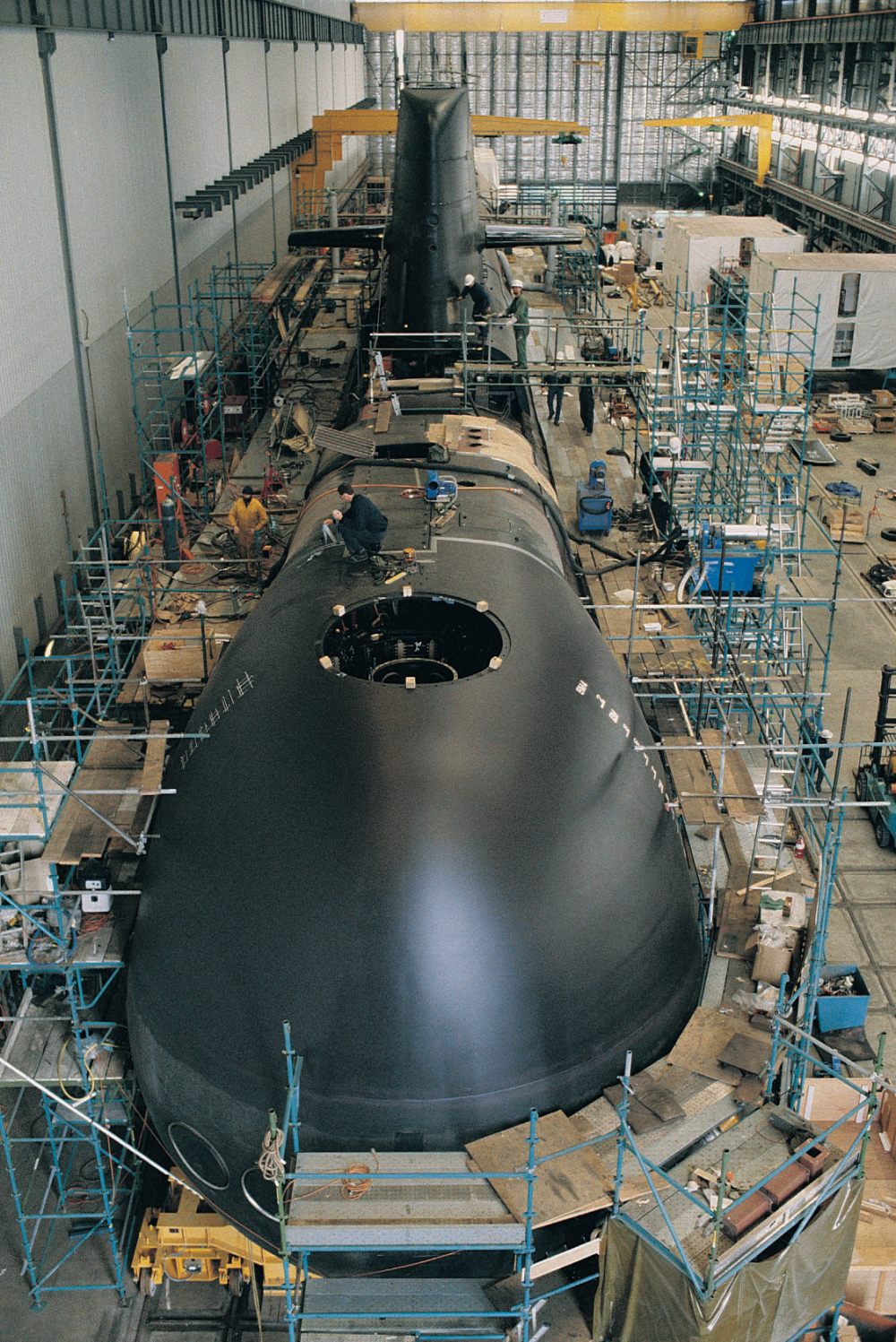

With a displacement of more than 10,000 tonnes, the SSN-AUKUS class will be larger than current US Virginia-class attack submarine of just over 7000 tonnes. Australia’s six conventionally powered Collins-class submarines are each about 3300 tonnes.

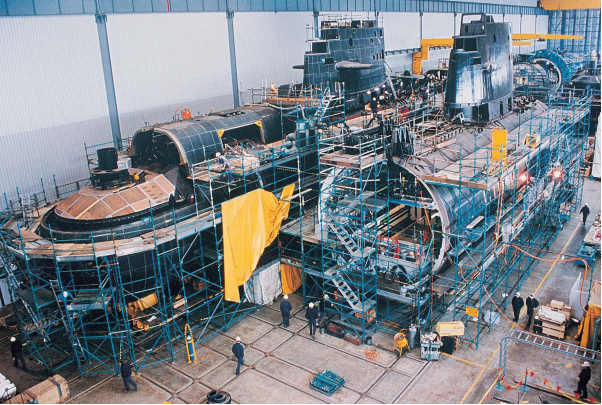

The SSN-AUKUS submarines to be built for Australia and Britain, with help from the United States, will be a ‘bigger, better, faster and bolder’ evolution of Britain’s Astute-class submarines, Mead says. The design will have the advantage of more US technology and greater commonality with US boats.

Australian steel will be used to build Australia’s SSN-AUKUS submarines, subject to a comprehensive qualification process expected to be completed in the first half of 2025.

The steel is also being qualified to both the British and US standards. Having Australian industry involved will deepen and bring resilience to the three nations’ supply chains, with greater mass, confidence and scale, Mead says.

In April, major US warship builder Newport News Shipbuilding lodged an initial purchase order for processed Australian steel from Bisalloy Steel’s Port Kembla plant for testing and training.

The government has committed to having eight nuclear submarines, Mead says, ‘and we’re on track’.

‘We’re planning on three Virginias and five SSN-AUKUS. That takes the program through to 2054.’

The SSN-AUKUS submarines built by Australia and Britain will be identical, incorporating technology from all three nations, including cutting-edge US technologies.

Those for the Royal Australian Navy will all be built at Osborne in South Australia. ‘Osborne will be the fourth nuclear-powered submarine shipyard among the three countries and one of the world’s most advanced technology hubs,’ Mead says.

The SSNs will all have an advanced version of the AN/BYG-1 combat system, used in the Collins class and in US submarines, and the Mark 48 heavyweight torpedo, an advanced version of which has been developed by the United States and Australia.

Mead says each Virginia has a crew of about 133 and the likely size of the SSN-AUKUS crew is being calculated as design work progresses.

The massive scale of the program and the nuclear element has understandably attracted strong attention, including criticism and questions about how skilled workforces will be found to build and crew the boats. Commentary has included suggestions that AUKUS is ‘dead in the water’.

Mead has no doubt that the project can be completed as planned. ‘Every day we ask ourselves the same question: ”Are we on track?” The answer is “yes.”’

For the program to succeed, it must be a national endeavour involving the Commonwealth, states and territories, industry, academia and the Australian people, Mead says. ‘To develop that social licence, we must provide confidence that we are going to deliver this capability safely and securely and not harm the environment.’

To build a nuclear mindset there must be an unwavering commitment to upholding the highest standards of safety, security, stewardship and safeguards, with all decisions underpinned by strong technical evidence. ‘It’s essential that everything we do is underpinned by strong technical and engineering evidence,’ he says. The reactor will be delivered as a sealed and welded unit that won’t be opened for the life of the submarine.

Mead acknowledges that recruiting is the big challenge.

He says comprehensive training of crews has begun, with Australian officers and enlisted sailors already passing nuclear training courses. ‘Australian officers have also topped courses in both the US and UK, showing that our people are up for the task that lies ahead.’

It’s intended that about 100 Australian officers and sailors will be in US training programs this year and they’ll go on to serve on US submarines as part of their crews. Other Australians will train in Britain and serve in Royal Navy boats.

Mead’s agency now has 597 staff, including engineers, project managers, lawyers, international relations specialists and policy makers. That is likely to rise to about 1000.

Given that Australia is the first non-nuclear nation acquiring nuclear-powered warships, the agency is working flat out to ensure rigorous regulations and safeguards are in place, along with the international agreements to back them.

Mead says Australia’s Optimal Pathway for acquisition of nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSNs) was designed to ensure that Australia would meet the exhaustive requirements to own and operate such vessels as soon as possible.

According to the Optimal Pathway, the first stage will see the first of several US and British submarines operating from the base HMAS Stirling in Western Australia as Submarine Rotational Force–West (SRF-West) from 2027.

In 2032, Australia will receive the first of three Virginia-class submarines from the US. One of the Australian officers now in US submarines is likely to be its commanding officer after extensive service on a US boat. The first two of those boats will be Block 4 Virginias, each with about 10 years’ US service, and they’ll be delivered after two years of deep maintenance and with 23 years of operational life left in them, Mead says, adding that the third US boat will be a brand new Block 6 Virginia. The US Navy has not yet put the Block 6 design into production.

The plan is to have the first SSN-AUKUS completed in Australia by early 2040s. Australia has an option to ask for two more Virginias if the SSN-AUKUS effort is delayed.

Mead says that how long the Collins are kept operational will be a decision for the government of the day as the SSNs arrive. The current plan is to begin big overhauls, called life-of-type extensions, for the Collins class in 2026.

He acknowledges that having the Virginias, SSN-AUKUS and Collin classes all operational could bring supply chain and training issues, but he believes those challenges can be handled. Having combat systems and torpedoes that are common to all these submarines will help.

Australians are on the design and design review teams for SSN-AUKUS. ‘We are embedding more technical and engineering people into the British program.’

Large numbers of Australian workers will soon be embedded in the British submarine construction site run by BAE Systems at Barrow, UK. ‘Many will come from the Australian Submarine Corporation, where they’ve been working on Collins. They’ll deepen their expertise, very specifically on how to build a nuclear-powered submarine,’ Mead says.

BAE will bring the intellectual property to the partnership with ASC to develop Osborne into a shipyard for nuclear-powered submarines.

It’s often suggested in Australia that, because the US has fewer submarines than it believes it needs, it will refuse to hand any over to Australia if its own situation worsens.

Senior American officials have expressed strong alternative views on why the project’s success is very important to the US and why it is in their own interests to make it work.

The US publication Defense News quoted the commander of US submarine forces, Vice-Admiral Rob Gaucher, telling a conference in April that co-operation with Australia would help the US submarine fleet in important ways. These included increasing the number of allied boats working together on operations. Having Australian personnel gaining experience on US boats would help ease a recruiting shortfall in the US Navy that flowed from the Covid-19 epidemic, and having access to the Australian base at HMAS Stirling in WA would extend the US Navy’s reach and maintenance options.

Gaucher said that, because the Australian SSNs would operate in co-ordination with American boats, ‘we get more submarines far forward. We get a port that gives us access’ to the Indo-Pacific region.

He said that by the end of this year the US Navy would graduate about 50 Australians as nuclear-trained operators and another 50 submarine combat operators. They would train on US submarines for the rest of this decade, increasing the number of people qualified to stand watch on American boats.

‘We get the opportunity to leverage an ally who can help us with manning and operating. We get surge capacity because now I have another area [where] I can do maintenance,’ Gaucher said.

Dan Packer, a former navy captain who is now the US director of naval submarine forces for AUKUS, told Defense News that Australia had eight officers in the inaugural training cohort that began in 2023. Three of those eight will be moved into an accelerated training pipeline, and one will eventually be the first Australian Virginia-class commanding officer.

Packer said the US was helping Australia build its submarine force from about 800 personnel to 3000. This year the US would bring 17 Australian officers, 37 nuclear enlisted and 50 non-nuclear enlisted into its training program. ‘And we’re going to up that number every year.’

These personnel would be fully integrated into US attack submarine crews until Australia could stand up its own training pipeline.

At some point, he said, the US Navy would have 440 Australians on 25 attack submarines, with each fully integrated crew including two or three Australian officers, seven nuclear enlisted and nine non-nuclear enlisted sailors. ‘They will do everything that we do’.

Mead says Australian navy personnel have been aboard the US submarine tender USS Emory S. Land for several months learning to maintain and sustain nuclear-powered submarines, and a US Virginia-class boat will visit HMAS Stirling for maintenance this year. Parts will come from an evolving Australian supply chain.

That visit will not include reactor work, ‘but ultimately, we will undertake work on systems that support the sealed power unit, within the compartment that houses it on the submarine,’ Mead says.

He says providing the industrial base to build and sustain the submarines, and crewing them, will involve about 20,000 jobs. A lot of work is being done with universities, technical schools and industry to prepare this formidable workforce.

Mead has long been a student of international relations and says the decision to equip Australia with SSNs was based on recognition that the Indo-Pacific is becoming a more dangerous place and ‘nuclear submarines provide a very effective deterrent’.

He rejects the argument that technology will soon make the oceans too transparent for crewed submarines to operate safely. ‘Our allies and partners and other countries in the region do not see it that way, and neither do we. We’ve done our analysis, and we see that crewed, nuclear-powered submarines will be the leading war-fighting capability for the next 50 to 100 years.’

He’s at pains to stress that the submarines will always be under full Australian sovereign control.

‘They will always be under the Australian government’s direction, operated by the RAN, and under the command of an Australian naval officer.’