Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

This is the 18th and final article in our series ‘Australia in Space’ leading up to ASPI’s Building Australia’s Strategy for Space conference, which begins today.

When I was the deputy secretary for strategy in the Defence Department, one of the things on my to-do list which never quite got done was to produce a public defence policy for space. Even back in palaeolithic 2009 it was slightly embarrassing that such a policy statement, classified and unclassified, didn’t exist. So many ADF capabilities relied on communications, IT, sensors and emitters that drew on systems operating in or through space. Indeed, wherever Defence links into Australia’s national infrastructure for logistic support, or engages with government decision-makers, or works with friends and allies, our complete reliance on the enabling effects of space systems is matched only by our utter vulnerability to those systems being damaged.

Why was I unable to produce such a policy statement? Looking back, four factors come to mind. One was the sheer number of players across the Defence tribes who felt they had a dog in the space fight. The department’s largest meeting rooms could be packed out with space stakeholders, typically at middle-level ranks, often individuals with very deep passions about the issues. In space, no one can hear you droning on relentlessly. While there were groups with interests big enough to block forward policy movement, the second problem was that no one section of Defence had enough control of space policy to champion change and spur faster policy development.

Third, notwithstanding the ‘critical enabler’ label that was attached to space, Defence’s senior leaders weren’t really galvanised by the issue. Not in the way they could be galvanised about the really big issues like platform acquisition or occupying floor space in the Russell headquarters. Space was ‘niche’—just like cyber used to be. And that was just inside Defence. Beyond the department was, well let’s call it Dimension X: an uncharted world of departments and agencies whose staff didn’t have security clearances (gasp!), bureaucratic decision-makers who were focused on economics (shock!) and politicians who didn’t think space was important (beam me up!). Policy phasers were set to stunned-mullet and had been locked like that for the better part of a generation.

Reading the excellent contributions to this series on Australia and space policy, one is entitled to hope that, in 2018, there are solid grounds to say things have changed for the better. By mid-year we’ll have an Australian Space Agency, which should aim to be the convening point for a national discussion on space policy, as well as a national champion and reasoned advocate for investment in and focus on space. There’s an emerging private-sector space industry and a range of affordable and scalable technology options that lower barriers to entering into space-related business.

Our contributors point to a confluence of technology developments, wrapping together the internet of things, artificial intelligence, autonomous systems and robotics into a slightly scary but very promising field. The good news for Australian entrepreneurs is that it’s smarts rather than scale which can get you into this business. Finally, there are one or two green shoots of hope that our major political parties are seeing the promise of more investment in space. There’s bipartisan support for the new space agency and for sustaining a meaningful defence industry base which will clearly be a central player in space technologies and systems.

A number of contributors, most prominently ASPI’s own Malcolm Davis, point to the reality that space is increasingly contested. In any substantial future conflict between major powers, it’s clear that space and cyber will be two of the earliest theatres of skirmishing as opponents look to disable each other’s military and national decision-making capabilities. In fact, cyber battles will probably occur over access to space and will use space-based communication systems themselves.

So a new factor driving national approaches to space is that all countries are faced with an increasingly stark choice to ‘use or lose’ their interests in space. Australia is acquiring at immense cost a fifth-generation–enabled defence force which, if we’re ever to fight with it, must have assured access to systems that rely on space. The US alliance provides fantastic access to key space systems; however, it could benefit from increased resilience from allied systems designed with it in mind. So a defence policy for space must set out how we’ll ensure that our forces have access to key systems inside our alliance with the United States and alone if necessary. (To give Defence credit, it produced a space policy in 2016—that’s one small step for planning.)

It could all still go wrong, though. First, the industry in Australia is incredibly small. Around 11,000 people are working in space-related businesses. To give you a sense of scale, the Department of Jobs and Small Business reports that 11,300 people worked as service station attendants in December 2017. Slightly more ominously, the same report recorded 11,900 motor vehicle parts and accessory fitters. By analogy it may be the case that our space industry sector is so far below critical mass that it might go the same way as motor vehicle assembly unless a transformative business development can break the industry out of a decaying orbit. Speculation that the Australian space industry will grow by three times its current size by 2030 to be worth $12 billion is just guesswork, although this growth rate doesn’t assume hyper-velocity expansion anytime soon.

I’m also not sure that Defence really has gotten over its tribalism or complacency about space, although I’d be happy to be corrected on this point. It’s one thing to talk the talk about a fifth-generation ADF, but quite another to galvanise delivering the enabling systems that are so space dependent. We’re still too focused on platforms, which anyone can see when discussions turn to the number of Joint Strike Fighters or submarines Australia will acquire.

Critically, while many advocates of Australia acquiring space capabilities exist, along with advocates of an Australian space industry, there are very few who are suggesting that they might trade off other spending plans they have to actually acquire real systems with real money in real budgets.

More broadly, Australians have grown used to living in a just-in-time world for energy supply, logistics, power, heating and cooling to the point that it’s only when the lights go out in Tasmania or South Australia that people realise there’s a complex but imminently vulnerable interconnected system of supply and distribution that sets the rhythm of our lives. And so much of this depends on access to and control of space. While our military forces think about the implications of operating in a ‘day without space’, our politicians should ponder what a day or two without space would do for the quality of social harmony in Australia. If satellites go down and there are no others that can provide redundancy and resilience, how long would it take to turn our urban centres into end-of-days theme parks?

But let’s end on a positive note. The arrival of the Australian Space Agency is a very welcome development. Business is buzzing with the potential for expanding space-related work. Defence has never been better equipped with space-enabled platforms and technology. A gaggle of new technologies—from swarming drones to artificially intelligent autonomous systems to dairy herds linked to the internet of things—all push Australia closer to a new and different type of space age. The cost of entry to space has never been lower. More than ever there is promise and excitement in the space business and every opportunity for smart Australians to shape this future.

This is the 14th in our series ‘Australia in Space’ leading up to ASPI’s Building Australia’s Strategy for Space conference.

A sustainable sovereign launch capability is essential for a strong and vibrant space industry. Without it, Australia lacks an essential component of industry integration and will always have to queue for a ride to space at a time and place not necessarily optimal for our economic or strategic benefit.

Like Australia, no country in Southeast Asia currently has a launch industry despite strong satellite development. Their need—like ours—is growing rapidly.

An Australian launch capability, in addition to supporting local companies, can generate significant direct export revenue. Canadian company Maritime Launch Services is forecasting eight launches per year at a cost of US$45 million per launch. Revenue earned from multiple sites and using different launch vehicles could amount to more than AUS$2 billion per year by 2025.

At least five Australian companies are developing vehicles to vertically launch satellites ranging in size from a few kilograms to hundreds of kilograms. All are seeking opportunities to launch small satellites and deliver the cluster of constellations expected to be deployed by 2025, and then replenish those every five to seven years. Worldwide there is intense competition among established and emerging launch vehicle builders.

New technologies such as the additive manufacturing (3D printing) of rocket engines and other parts could see manufacturing co-located with a spaceport, enabling rapid supply of vehicles—reducing build and transport costs. Recovering rocket stages and then refurbishing or recycling them will further reduce overall launch costs.

‘Horizontal launch’ of satellites from aircraft could be another option to achieve orbit, but aircraft limitations are likely to restrict payloads to small satellites weighing less than 500 kilograms. Another concept is that of ocean launches using floating rockets, an idea being pursued by Ripple Aerospace. A novel concept being developed by 8Rivers is a tube-launched electric rocket that leaves its power supply on the ground.

Forty US‑based launch companies will participate in the recently announced DARPA Launch Challenge. Europe and Asia have a similar number of rocket builders. All in all, this is a very competitive industry, which is leading to a significant decrease in the cost to launch.

For Australia, space launches started in the mid‑1960s with the launch of the Europa vehicles from Woomera. Twenty years later, governments across Australia looked to re‑enter the space race, with sites considered in Cape York and in the Northern Territory at Darwin, Gunn Point, Point Stuart and Nhulunbuy.

Since then commercial organisations have investigated establishing spaceports at Christmas Island, Woomera, Rockhampton, Derby, across Australia’s southern coast, and at all the Northern Territory locations considered in the mid‑1980s.

Today a spaceport and associated range are being developed in Arnhem Land 25 kilometres south of Nhulunbuy by Equatorial Launch Australia. Land has been leased, and agreements have been established with domestic and international organisations for the supply of rockets capable of lifting into orbit payloads ranging from three kilograms to more than 7,000 kilograms. Over the coming years, subject to regulatory approvals, there should be regular launches of satellites and spacecraft to deep space from the Arnhem Space Centre.

Establishing a spaceport requires careful consideration. Cost constraints mean that extant infrastructure needs to include an airport, seaport, weather radar, high-bandwidth global connectivity and mobile phone coverage. Low population densities help to lower risk and insurance costs, while quick access to hospital emergency facilities is required to meet safety requirements. A local skilled workforce can be a base to build supporting industries, but importantly, there’s a need for demonstrated support from the community and traditional owners.

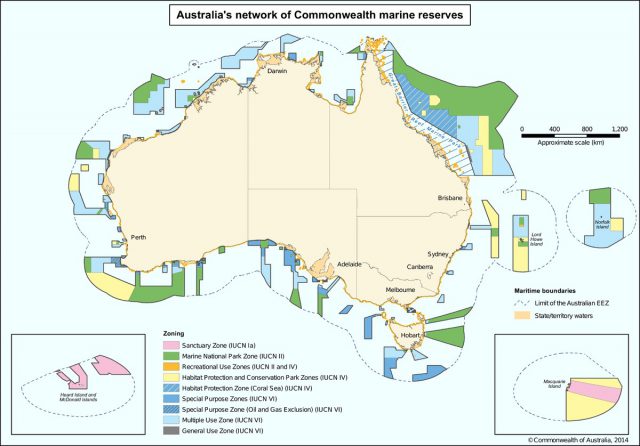

Open ocean next to a site is preferred to allow safe flight termination if there’s a malfunction, and for dropping stages in zones away from people. Marine reserves (Figure 1) will limit most coastal site options, especially in eastern Queensland. Launch corridors over land are possible, but would require extensive consultation and agreements with governments and land owners over many years. Oil and gas infrastructure also restricts the potential for northerly blast offs from Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

Figure 1

The further a site is from the equator, the less benefit it gains from the earth’s rotation, which imparts increased velocity when launching to the east. To be competitive, higher latitude sites tend to specialise in launching north–south polar orbits, primarily for earth observation.

The equatorial low‑earth orbit (Figure 2) is a particular orbit of economic and strategic interest for Australia and our allies. Encompassing the equatorial zone between +/- 15 degrees, this orbit covers three billion people in Southeast Asia, most countries in Africa and South America, and many Pacific nations.

Figure 2

From a satellite operator’s perspective, a constellation flying in this zone only needs one‑tenth the number of satellites of a similar global constellation—potentially an order of magnitude’s cost savings.

The global space launch market was valued at US$8.7 billion in 2016, and is projected to reach US$27.2 billion by 2025, a 15% compound annual growth rate. Globally this market is very strong, and the strongest projected growth is in the Asia–Pacific region.

Key factors driving the growth of the launch market are a rise in space exploration activities, technological advancements to develop low-cost vehicles, and an increase in demand for small satellites and constellations. On 31 August 2017 there were 1,071 active satellites. That could increase tenfold within five years.

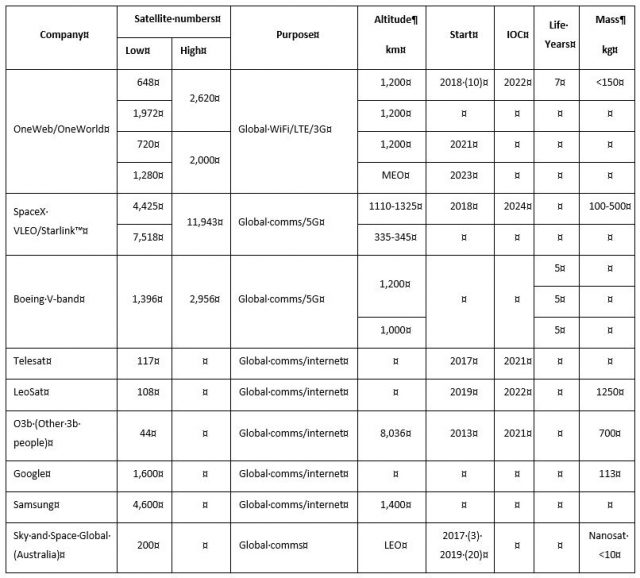

Forecast satellite constellations derived from published sources

From 2025, there could be a further rise in deep-space activities associated with off-earth resource extraction. That would produce additional strong demand for efficient equatorial launches of both small and large payloads.

There’s now growing momentum to create a sustainable, flexible and responsive sovereign launch capability that can underpin a globally competitive space industry in Australia.

This is the 11th in our series ‘Australia in Space’ leading up to ASPI’s Building Australia’s Strategy for Space conference in June.

The ability to make intelligent decisions is supported by access to timely, reliable, superior information. Access to superior information gives businesses a competitive advantage and provides a strategic advantage to defence.

Space is an increasingly important source of information. Satellite systems support communication; positioning, navigation and timing (PNT); and earth observation. This space-derived data is then combined with other data sources to deliver value across a wide range of industries.

How do we ensure that Australia has access to the data that best serves our needs and gives our companies and defence the strategic advantage we desire?

This is a complex question and one that the new Australian Space Agency has been tasked to answer. Any response must span all three satellite applications and consider the needs of government, industry and defence.

Our ability to deliver and use superior space-derived information is related to our infrastructure and skills. It relies on our ability to develop a user community that understands the sector’s needs, understands the strengths and weaknesses of the various solutions, can provide the requirements for new solutions, and can integrate new solutions into their existing operations.

The most mature commercial market for satellite data is communication. Since the government first invested in infrastructure back in 1979 through AUSSAT Pty Ltd, the sector has grown to more than 21 companies active in commercial satellite communications (Communications Alliance). Optus Satellites now has more than 30 years’ experience in commercial satellite operations and employs more than 150 people in space-related roles. It currently operates five Optus satellites, two NBN satellites and 94 ground stations, hosts a payload for defence and has supported more than 90 international missions.

The future needs of the sector are being supported through groups like the Institute for Telecommunications Research and the development of optical communication systems at the ANU, UNSW and the University of Western Australia.

We’re also seeing the emergence of companies using small satellites. Myriota is deploying a network of low-power microtransmitters that transmit a narrow bandwidth signal to a constellation of small satellites in low-earth orbit. Optus and Myriota both use satellite communications platforms, but they serve different and complimentary markets. With high power and high bandwidth, Optus can deliver persistent video and internet services, whereas Myriota provides a low-cost solution to assist users to monitor distributed assets.

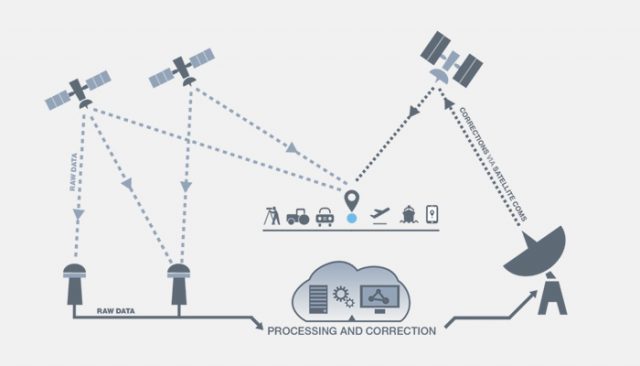

In the 2018–19 Budget, the government announced a $260 million investment in SBAS (Satellite-based Augmentation System), PNT infrastructure and Digital Earth Australia. The investment in SBAS and PNT will improve location accuracy in Australia from 10 metres to 10 centimetres, laying the foundation for the next generation of autonomous systems for agriculture, mining, aviation and more.

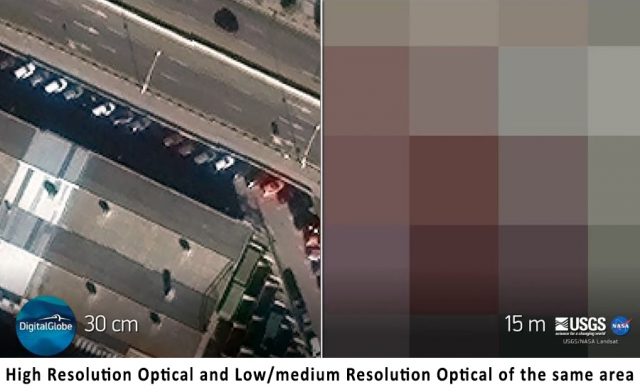

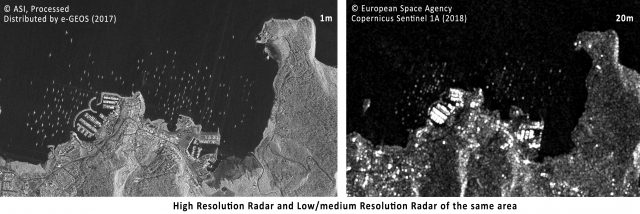

Australia doesn’t have any earth observation satellites. We access low- to medium-resolution imagery from satellites such as the ESA Copernicus and USGS Landsat constellations through intergovernmental agreements. The investment in Digital Earth Australia makes this archive available to government departments and industry free of charge, providing users with 10-metre-resolution optical imagery every five days.

Australia accesses high-resolution imagery through commercial arrangements with international providers. This gives us access to high-resolution optical and radar satellites from multiple countries on an as-needed basis.

However, Australia is the only OECD country, and one of few countries in the Asia–Pacific, that doesn’t have direct receiving stations for these systems. Without the ability to downlink data in Australia, we receive imagery six to 24 hours after submitting a request (compared to 20 to 40 minutes with direct downlink), pay higher costs, and can’t directly task the satellites.

Australia has access to broadband communication, and with the investment in SBAS we’ll have high-precision positioning. But due to a lack of infrastructure, our access to high-resolution earth observation data is slower and more expensive than other countries’ and we can’t directly task these satellites. If it was entirely a commercial decision, industry would invest in the infrastructure, but as with communications and positioning infrastructure, the benefactors are government, defence and commercial companies across multiple industries.

There are some exciting examples of how these systems are being used. The Australian Maritime Safety Authority uses Satellite AIS (Automatic Identification System) to track ships. exactEarth’s recent move from a constellation of small low-earth satellites to hosted payloads on more than 60 Iridium Next communications satellites will make it possible to track ships with a latency of less than one minute. Many Australian companies, including Geospatial Intelligence Pty Ltd, integrate AIS data, high-resolution radar and optical imagery, and other data sources to develop products and services for customers that need high-quality information quickly. With access to a ground station in Australia, this could include search and rescue.

This is an exciting time for the space industry as miniaturisation and improved computer processing are driving down the size, weight and cost of satellites and opening new possibilities for constellations of small satellites. However, the laws of physics still hold. The performance of these satellites is limited by the size of the instrument, the available power, the on-board storage, and the ability to launch and replenish constellations. Small satellites won’t replace large satellites, just as satellites won’t replace aerial observations, but a range of options are emerging that deliver greater capability and efficiency for users.

The real power is in the integration of multiple sources of information. Australia has an opportunity to become an intelligent customer and a sophisticated user. We can develop our own systems where the market doesn’t meet our needs and draw on all the available technologies to deliver a competitive advantage for businesses, and a strategic advantage to defence.

This is the eighth in our series ‘Australia in Space’ leading up to ASPI’s Building Australia’s Strategy for Space conference in June.

Australia depends on satellite data for everything from defence surveillance and weather forecasting to restocking supermarket shelves and synchronising mobile phone conversations.

But for all of these things, it mostly depends on satellites designed, built and launched by others.

Yes, that has begun to change. Australia funded one of the satellites in the Wideband Global SATCOM (WGS), a system that gives the Australian Defence Force enhanced interoperability with the US and other allies.

The ADF also benefits from access to commercial satellites such as the Optus C1 and, potentially, from the work on cubesats undertaken by Australian universities.

But these developments haven’t altered the bigger picture, which is that Australia continues to be largely a free rider in space technology.

If the ADF and much of Australia’s industry, commerce and agriculture were suddenly deprived of the satellite access provided by governments and companies in other nations, principally the US, there would be chaos.

It may be objected that this is unlikely to happen, although in an increasingly uncertain strategic environment that cannot be said quite as confidently as might have been the case earlier in the decade.

In a conflict between major powers in the western Pacific, for example, competition for access to satellites would be intense.

Whether or not such a clash ever happens, the fundamental point is clear: Australia is vulnerable, militarily and economically, while we lack sovereign capability in space technology.

That’s the most important reason why we should develop a national space industry with the capacity not only to design satellites for our needs but to build and launch them as well.

Another reason, flowing from the first, is that by acquiring these capabilities Australia will be able to take a larger stake in the global commercial space industry, which is growing by 10% annually. At present the global industry is worth $420 billion, of which Australia’s share is only 0.8%.

Australia’s nascent space sector earns revenues of up to $4 billion a year and employs about 11,000 people. The Space Industry Association of Australia estimates that this could double within five years if there’s strategic leadership at the national level, including public investment measures.

This isn’t only about taking advantage of immediate commercial opportunities. Even more importantly, an expanded space industry would enable Australia to transform its broader manufacturing sector in line with the so-called fourth industrial revolution, or Industry 4.0.

This is crucial for both military and commercial applications of space technologies. Space-based systems are essential for Industry 4.0 capabilities that modern smart factories, which are integrated cyber–physical systems, depend on: big data, cloud computing, artificial intelligence and the internet of things.

The era of Industry 4.0 coincides with what Malcolm Davis, in his ASPI report Australia’s future in space, terms Space 2.0, the emergence of low-cost technologies such as the Biarri and Buccaneer cubesats developed by the UNSW/ADFA. This is a time of opportunity for a country such as Australia; what is lacking is action at the national level to ensure that the opportunities are seized.

That’s unlikely to happen while Australia remains one of only two OECD nations to lack a national space agency. The Turnbull government and the Labor opposition have both announced their support for the creation of such an agency, but to date the government’s announcement hasn’t been followed by specific details of when the agency would be constituted and what it would do.

Those details, the government insists, should wait until after the conclusion of a comprehensive review of Australia’s space industry capabilities. The review was supposed to be released in March this year, but at the time of writing there’s no indication of when it will actually appear.

The review, which is being conducted by an expert reference group chaired by the former CSIRO chief, Megan Clark, will no doubt do its work well. But enough is already known about what needs to happen for the space industry to expand. What is missing is the government’s willingness to act.

Labor has already outlined a plan for an Australian Space Science and Industry Agency to drive investment and coordinate action by industry, universities, research institutes and other government agencies. The agency would be advised by a Space Industry Innovation Council, and a Space Industry Supplier Advocate would be appointed to promote opportunities for Australian firms.

A Labor government would invest up to $35 million in an Australian Space Industry Program, with co-investment to be sought from industry and university consortiums. The program will consist of four Australian Research Council (ARC) space industry research hubs—to advance capabilities in space technologies—and two ARC industry training centres that would offer 25 industry-based PhDs.

All this could be done now, and we know that similar measures have enhanced innovation and productivity in other industries. Australia only needs to find the will to make it happen.

The 2016 Defence White Paper, in considering the ADF’s approach to the use of outer space for military purposes, highlights a significant potential path for the ADF, and more broadly, for Australian space policy in the 21st century. So why is space important for the ADF, and what does the 2016 DWP say about the issue?

The 2016 Defence White Paper, in considering the ADF’s approach to the use of outer space for military purposes, highlights a significant potential path for the ADF, and more broadly, for Australian space policy in the 21st century. So why is space important for the ADF, and what does the 2016 DWP say about the issue?

In World War Two, Bernard Law Montgomery claimed, ‘If we lose the war in the air, we lose the war and we lose it quickly’. This famous axiom translates well to space today, where an inability to access military space capabilities completely undermines the ability of modern information-led military forces to function—forcing them back to a cruder, industrial level of conflict. That type of warfare is characterised not by multidimensional manoeuvre, precision attack and a ‘knowledge edge’, but by mass, attrition, the ‘fog of war’ and the less discriminate use of firepower leading to high casualties, both military and civilian. Think of battles such as the Somme or Stalingrad—or even Syria today.

Ensuring continuing access to space capabilities is vital for our military to function effectively and for us to be able to use military power in a manner that’s consistent both with the Just War theory that emphasises proportionality and discrimination in the use of force, and the current values upon which our society is based, particularly in wars of choice. New air, naval and land forces highlighted in the 2016 DWP are enabled by space capabilities, from our reliance on global communications and the use of precision navigation to support joint expeditionary operations, to ensuring an effective understanding of the battlespace through space-based ISR. This dependence on space will only grow over time as the ADF becomes more network-centric. Further, if we seek true interoperability with coalition partners we must be able to plug and play with their space systems. Simply put, our ability to use space is vital to our entire approach to defence, and that’s not going to change.

The 2016 DWP recognises this and is laying the basis for an expanding ADF military space capability. It begins by highlighting that Defence will enjoy ‘…greater access to allied and commercial space-based imagery capabilities, and this will lay the basis to potentially develop new space-based sensor capabilities.’ (4.14) The White Paper also reiterates the importance of space surveillance and situational awareness through ‘…the establishment of the space-surveillance C-band radar…and the relocation of a US optical Space surveillance telescope’ to the Harold E. Holt Naval Communications station near Exmouth in Western Australia (4.16). Finally it reinforces the prospect of investment in ‘…ADF space capability, including space-based and ground based intelligence, reconnaissance and surveillance systems.’ (4.16)

Two significant messages on space need to be highlighted. The first is a recognition of the importance of sharing space capabilities with allies, such as the US, but also potentially other important allies that have growing space capabilities. Earlier analyses by Andrew Davies, Rod Lyon and myself have already suggested Japan as a possible candidate amongst others as a new partner in space with a coalition approach adding to dissuasion that strengthens resilience in the face of adversary counter-space capabilities. Second, the 2016 DWP recognises the importance of commercial space-based sensor capabilities as an alternative to a government-run ‘mil-spec’ project, for Australia investing in new space-based sensor capabilities.

More fundamentally, the DWP lays the policy basis for Australia to embark on a more ambitious approach to space capabilities in the future than it has previously, when Australia was content to be a passive consumer of Space services provided by other states. DWP 2016 hints that Australia may instead be a producer of space capabilities, and is congruent with accelerating efforts within Australian private space companies and universities to develop commercial space capabilities and undertake R&D aimed at establishing an Australian space capability to ensure that Australia’s more than a passive observer on the sidelines as other states dominate the space sector. That approach is based around the use of commercial small satellites and ‘CubeSats’. In terms of launching those payloads into Space, the key technology to watch is reusable rockets that are now entering service in the US as part of a rapidly expanding commercial space launch sector. By dramatically reducing the cost of space launch through re-using the rockets, the potential for financial risk drops away as well. That opens up the high frontier to a much wider spectrum of users, including would-be Space powers such as Australia.

DWP 2016 establishes the policy foundation upon which much can be built at a highly opportune time of revolutionary shifts in space technology and great interest in the commercial Space sector. Consider also that moves are underway to review and update (and here) the 1998 Space Activities Act, which is no longer relevant. This policy process which brings together government, the private sector and universities can and should incorporate input from the Defence community as a key user of space. The Defence Innovation Hub, announced alongside the DWP as part of the Defence Industry Policy, clearly has a key role in this regard.

Australia’s space policy choices are at an inflection point. New approaches to using space, launching payloads and the design of space capabilities is dramatically changing the way states and non-state actors use space. The impact of disruptive innovation in the commercial sector is increasingly clear, and the timing for the review of the Space Activities Act, along with the policy foundations established by the 2016 Defence White Paper, is fortuitous. It’s often said that ‘fortune favours the bold’. Now is the time for Australia to be bold in space.

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria