Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Should Vietnam continue building its maritime forces or should it pivot landward to best ensure its security? Few would dispute that this is a critical question that merits close scrutiny. As an emergent middle power, Vietnam simply doesn’t have sufficient resources to simultaneously pursue a powerful navy and a muscular land army. Making appropriate strategic trade-offs is therefore vital to ensuring national security.

However, the recent discussion on this forum about Vietnam’s geostrategic orientation, sparked by Khang Vu’s article, misses a vital point. Debating whether the Vietnamese military should expand landward or seaward adds little value if the kind of future security threat and the scenario under which Vietnam would be attacked are not clearly and accurately specified. After all, beefing up a nation’s military doesn’t improve national security if the weapon systems purchased, and the military doctrine developed, don’t match the most probable threat.

In their Strategist piece, Euan Graham and Bich Tran essentially argue that the Vietnamese military should continue the current maritime focus because Vietnam’s export-oriented economy is dependent on freedom of navigation in the South China Sea. They are concerned that Vietnam could be vulnerable to a blockade should China have ‘uncontested control within the so-called nine-dash line, and acquire access to a naval base in Cambodia’. However, they don’t specify what ‘uncontested control’ means and what would trigger China to blockade Vietnam. Because of that, it’s not clear why this naval blockade should be the nightmare scenario for Vietnamese policymakers and how a Vietnamese naval buildup could forestall such an outcome.

While Nguyen The Phuong is sympathetic to Graham and Tran’s view that Vietnam should prioritise investing in its maritime capabilities, he does a better job of specifying the critical threats that Vietnam might face in the future. According to Nguyen, Hanoi should be most concerned about a military conflict in the South China Sea, which would follow (presumably Chinese) pre-emptive strikes using long-range weapons and cyberattacks. The other nightmare scenario would be ‘a maritime blockade of Vietnamese outposts in the Spratly Islands’. The clear assumption here is that by investing in maritime capabilities, Vietnam could deter China from contemplating or taking such aggressive action. However, as the Russo-Ukraine war has shown, when the attacker is much more powerful than the defender and is determined to wage war, it’s likely that no form of deterrence short of nuclear deterrence would be effective.

In contrast to the previous authors, Vu maintains that Vietnam should prioritise its land forces because fighting land wars has always been more critical to Vietnamese security than the maritime domain. While I agree with him that land-based threats clearly pose a greater danger to Vietnamese security, I can’t see how investing in a powerful land army would prevent China from turning Laos and Cambodia against Vietnam. Whether Vietnam can ensure that its two neighbors remain on friendly terms is up to its foreign policy and diplomatic agility, not its army. Also, it isn’t clear what Vu is arguing for in practical terms. Assuming that land-based threats are more severe, what should Vietnamese leaders focus on? More specifically, what kind of force posture should the Vietnamese army adopt and to what strategic ends?

Because Vietnam sits on mainland Asia but has a long coastline, it has to inevitably prepare for both kinds of threats over the long haul. However, because the sovereignty contest over the South China Sea will not conclude anytime soon and Vietnam has made great strides in demarcating land borders with all of its neighbors, it is more likely that armed conflicts in the near future will be maritime-based rather than land-based. The critical questions therefore are: under what circumstances would such conflict likely to erupt, and what would it look like?

In his 2008 study of China’s approach to territorial disputes, M. Taylor Fravel points out that Beijing has a pattern of acting aggressively in disputes over territory to halt a decline in its bargaining power vis-à-vis other parties. In other words, we should be most worried about China waging armed conflicts when Beijing feels insecure because its power is declining to the extent that it can no longer enforce its territorial claim, or because other states are taking drastic actions to expand their control over disputed territories. This logic explains why China has refrained from invading Taiwan yet always reacts forcefully to any hint of Taiwanese independence. Based on this line of thinking, a defensive posture that doesn’t seek to diminish Chinese control over a piece of disputed territory is likely to be more successful in preventing or at least delaying conflict.

Assuming that any future armed conflict between China and Vietnam would be over the South China Sea, it would most likely erupt when Beijing felt it was losing its grip over some of the disputed islands because it has experienced decline or because other parties are banding together to solve their disputes without China’s participation. And should China initiate conflict out of insecurity, it would likely aim for a swift fait accompli rather than start a massive naval war. For example, it could seize one or two islands controlled by another country and then challenge the defender to escalate the conflict and risk starting a war to recapture the lost territory. That would allow China to assert its sovereignty and regional dominance at lower costs and risks, similar to Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

The key challenge for Vietnam, therefore, is not to deter a maritime war but to develop the right kind of maritime capabilities that would allow it to fight effectively in the grey zone. More precisely, it needs a robust naval militia that could deny China outright control over any disputed island without openly escalating the conflict to the level of war. Missiles and fighter aircraft would not be helpful here. Radars and a robust fleet of well-equipped patrol ships that could react quickly and forcefully would play a more vital role in maintaining the status quo. The strategic goal is to deny a successful fait accompli and create space for diplomacy to defuse the crisis.

It’s in these specific terms that we should continue a debate about Vietnam’s strategic choices. The broad binary choice between a landward focus and a maritime orientation is unproductive. What’s critical is that the military be geared to fight and prevail in the sort of conflict that could break out, whether on land or at sea.

With China increasing the pressure both on land and at sea, Vietnam is facing a hard choice: should it continue its maritime tilt adopted since the early 2000s or should it pivot back to the land like it did throughout the Cold War years? Recently, I argued that Hanoi should prioritise its land security because, historically, amassing the resources to build and maintain an army and a navy at the same time has proven to be beyond Vietnam’s capacity, and Hanoi has always focused on its land-based threats before thinking about the sea. It kept silent when China annexed the Paracel Islands in 1974, and its response to China’s occupation of the Johnson South Reef in the Spratly Islands in 1988 was weak simply because it was fighting land wars against South Vietnam and the Khmer Rouge as well as China. In the minds of Hanoi’s leaders then, the Paracels and Spratlys didn’t matter to Vietnam’s survival.

In this context of the debate on Vietnam’s grand strategy in the 21st century, Euan Graham and Bich Tran’s response to my argument is a welcome addition. The two authors argue that Hanoi needs to maintain its pivot to the South China Sea because Vietnam’s prosperity is linked to freedom of navigation and abandoning the sea might lead to a Chinese blockade of Vietnamese ports and the deprivation of Vietnam’s offshore economic interests. Importantly, they contend that China’s continental threat to Vietnam is not as grave as its maritime threat and therefore that Vietnam doesn’t have to worry as much about its land security. While that argument makes sense if we look only at Vietnam’s strategic environment over the past 20 years, it doesn’t hold when considering how Vietnam’s land security has directly affected its maritime security and its economic development policies since its establishment in 1945.

Graham and Tran point to an economic origin for Hanoi’s security policies, noting that Hanoi’s export-driven economy is tied to its access to the ocean and that the country’s 21st-century focus on the sea is to protect those economic interests. However, that narrative ignores why Vietnam decided to adopt an export-driven economy under the 1986 reforms known as Doi Moi (restoration) in the first place, and that reason has to do with land security. Hanoi contemplated the idea of economic decentralisation many times, but implementing such a policy during the Vietnam War was politically and economically impossible. After unification, decentralisation was put on the back burner because Vietnam still needed a wartime command economy to support its occupation of Cambodia and large-scale military presence along the border with China.

Only after Vietnam withdrew from Cambodia in 1989 and normalised ties with China in 1991, indicating a fundamental change in its land security environment, did Doi Moi really take off thanks to the lifting of international sanctions and the massive demobilisation of Vietnamese armed forces in service of domestic economic production. Remarkably, Vietnam has lost the Paracel Islands since 1974, but that didn’t hurt its post–Cold War economic growth. Improvements in relations with the West and the foreign investment that followed were the result of Vietnam adopting a friendlier security policy towards its neighbours, not because of a maritime tilt.

In short, Vietnam’s Doi Moi policy and export-driven economy are dependent on secure land borders. The external security environment drives Hanoi’s economic policies, not the other way around as Graham and Tran suggest. As an autocratic state, Vietnam will surely reintroduce a wartime economy again if its land security deteriorates sharply.

While underestimating the land threats, the two authors exaggerate the maritime threats to Vietnam’s security. Although most of Vietnam’s population and infrastructure are concentrated on the coast, an amphibious invasion from the sea is militarily difficult and unlikely. Chinese leaders are aware of the risks of an amphibious invasion of Taiwan, a country much smaller than Vietnam in terms of population and territory. It is illogical for China to take a detour when it can directly attack Vietnam from the north, as it has done a number of times over the past 2,000 years.

Even if China decided to ‘teach Vietnam a lesson’ from the sea, Vietnam could fall back on the mountain ranges in the west, a strategy that the Vietnamese communists used to drive the French and the Americans out of the river deltas. And this strategy further stresses the importance of Vietnam’s land security. Allowing China to wrest Laos and Cambodia from Vietnam would deprive Hanoi of strategic depth. As I have argued elsewhere, the best way for Vietnam to protect its maritime security is to first and foremost ensure it is safe on the land, including both its western and northern borders. China’s occupations of Vietnam’s islands didn’t bleed the country dry, but the presence of Chinese troops along the border did.

Hanoi’s 21st-century maritime tilt is built on successful land security policies from the century before, and it is easy to ignore success on the land and focus on the challenges on the sea. In an ideal situation, Vietnam shouldn’t have to choose between land and maritime security. But as Graham and Tran note, Vietnam’s geography influences its strategic choices. Hanoi should keep asserting its maritime interests to an extent within its means, but its priority has been and will always be on the land.

Since its October release in draft form, China’s new coastguard law has been the subject of dozens of news reports and analyses. Maritime law enforcement legislation rarely attracts such international attention, but in this case it is warranted. For 15 years, the China Coast Guard has led the country’s seaward expansion into areas long claimed but seldom (if ever) visited. International observers are right to wonder, what does the new law portend for Chinese behaviour at sea?

Many have focused on the law’s use-of-force provisions. In the past, the China Coast Guard has employed a wide range of coercive tactics to achieve Beijing’s strategic and operational objectives. Last April, for instance, a 3,500-ton Chinese coastguard ship rammed and sank a Vietnamese fishing vessel operating in waters also claimed by Hanoi (Beijing implausibly suggested the wooden-hulled Vietnamese boat did the ramming). However, to date it has avoided using armed force against foreigners.

The new law signals that that could change. Article 47 authorises armed China Coast Guard personnel to forcibly board noncompliant foreign vessels ‘illegally’ engaged in economic activities in Chinese-claimed waters. Article 48 allows the use of shipborne weapons (that is, deck guns) in cases where coastguard forces face attack by weapons and ‘other dangerous methods’—which could mean anything. Even more ambiguous, Article 22 allows the coastguard to employ ‘all means necessary including the use of force’ to stop foreigners found infringing Chinese ‘sovereignty, sovereign rights and jurisdictional rights.’

While disturbing, the use-of-force provisions are not the most worrisome elements in the new law. Rather, it is the ambiguous geographic scope of the law’s application: China’s ‘jurisdictional waters’ (管辖海域). The draft law only vaguely defined the term (Article 74). In the final version, passed on 22 January, that content was removed, leaving no definition at all.

However, a close reading of authoritative Chinese sources reveals that Beijing claims jurisdiction over 3 million square kilometres of maritime space, often called China’s ‘blue national territory’. This comprises the Bohai Gulf; a large section of the Yellow Sea; the East China Sea as far east as the Okinawa Trough, including waters around the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands; and all the waters within the ‘nine-dash line’ in the South China Sea. By Beijing’s own reckoning, ‘over half’ of this space is contested by other countries.

If the China Coast Guard followed the letter of the new law, what would we see? In the South China Sea, any foreign fishing, survey or research vessel found operating anywhere within the nine-dash line would be subject to boarding and inspection (Article 18). Refusal to comply would mean a forcible boarding by armed personnel prepared to compel them to do so (Article 47). The China Coast Guard would send units to dismantle the structures on every Vietnamese-, Philippine- and Malaysian-occupied land feature in the Spratly Archipelago (Article 20). In the East China Sea, the coastguard would sail to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands and ‘expel’ every Japanese ship it encountered (Article 17). In the Yellow Sea, East China Sea and South China Sea, the coastguard would track down and evict US Navy ocean surveillance ships like USNS Impeccable and hydrographic survey ships like USNS Bowditch for conducting ‘illegal’ activities in China’s exclusive economic zone (Article 21).

Fortunately, just because Beijing has a law on the books doesn’t mean that it will actually enforce its provisions. This is certainly true in the maritime realm. For example, China’s national fisheries law, last updated in 2013, authorises China’s maritime law enforcement forces to punish and expel (Article 46) foreign fishing vessels operating illegally in China’s jurisdictional waters. Yet there remain vast sections of China’s ‘blue national territory’ where they continue to operate unmolested.

In recent years, China has adopted several new laws and regulations that seemed to presage new coercive behaviour that never occurred. For example, in 2012 and 2013 Hainan province issued two new maritime laws, one on fisheries management and one on public security. Nether has apparently made things worse for foreign mariners, despite concerns they would.

In August 2016, the Chinese supreme court issued judicial interpretations authorising the China Coast Guard to charge foreigners for criminal offences if caught ‘poaching’ in Chinese jurisdictional waters. Since then, the coastguard has not enforced this provision, despite many chances to do so. Thus, new laws have not necessarily meant new coercive behaviour. It seems unlikely that this one will either.

Why? Because enforcing these laws against foreign mariners is above all a political decision. It is a question of foreign policy, not domestic policy. And applying them by the book would be terrible foreign policy. Beijing would further alienate its neighbours, pushing them closer to its rivals, the US and Japan. It would make it much harder for Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam to remain neutral in the current period of great-power competition. It would risk erasing all the hard work done to lure Manila away from its alliance with Washington. And it would mean war with Japan and the United States.

This doesn’t mean that regional states should simply ignore the coastguard law. Far from it. When the draft was issued in October, an official ‘explanation’ listed four reasons why it was urgently needed. The first cited requirements associated with building China into a ‘maritime great power’ and ‘safeguarding maritime rights and interest’—the code words for ‘do a better job defending China’s maritime claims’.

Clearly, Beijing expects the law to benefit its cause in some way. Moreover, Chinese policymakers inserted the most coercive provisions in the new law because they clearly imagined situations when applying them would make political sense. So, even if the chances of a major new provocation are small today, regional states must take substantive steps to prepare for that possibility in the future.

Smart leaders will do more than that. In June 2012, Vietnam passed a new maritime law that defined the geographic extent of its own maritime boundaries, including territories occupied by China. In retaliation, China established Sansha City, opening the door to major expansion of Chinese administration of disputed space in the South China Sea. If China can take foreign legislation seriously, so can others.

Aside from being vigilant and shrewd, what else might regional states do? At the very least, they should tell Beijing that they will never accept the law’s application against their citizens in disputed waters and warn of severe consequences if China does so anyway. In the age of great-power competition even small states have leverage. They should also demand that China provide a precise definition of its ‘jurisdictional waters’.

In authorising its coastguard to use deadly force to uphold its maritime claims, Beijing has crossed a line. Foreign diplomats should tell their Chinese counterparts that ambiguity of any kind is simply no longer acceptable.

China’s new law giving the China Coast Guard more freedom to use force has increased the concerns of China’s neighbours. The Philippines filed a formal rejection of it on 27 January, emphasising that, given the large area involved and China’s ongoing disputes in the South China Sea, the law is a verbal threat of war to any country that defies it.

On 8 February, a week after the law came into effect, China’s largest maritime patrol vessel, Haixun 06 (海巡06), was launched from Wuhan shipyard. It will be used for ‘regulating Taiwan Straits’ waters, preventing pollution, dealing with maritime incidents, cross-strait exchanges and maintaining national maritime sovereignty’, according to the Fujian Maritime Safety Administration. As the administration sits within the Ministry of Transport rather than the CCG, such developments indicate that the new law is a threat not only because it allows the CCG to use force, but also because it expresses China’s determination to pursue ‘near-seas defence with far-seas protection’ (近海防禦、遠海防衛) by mobilising national resources in support of the CCG to achieve full control of China’s ‘near sea’ regions.

The law aims to consolidate the CCG’s role in near-seas defence (近海防禦). Articles 2 and 3 clearly state that the Coast Guard Authority (海警機構)—which refers to the Chinese People’s Armed Police Force Coast Guard Corps (人民武裝警察部隊海警部隊)—is responsible for protecting China’s maritime sovereign rights and conducting law enforcement operations in ‘jurisdictional waters’ (管轄海域).

The law emphasises the integration of political, military and civilian resources to support the CCG’s development. It says that the State Council, local government and the military should strengthen collaboration with the CCG (Article 8) and compile national spatial plans according to the CCG’s requirements for law enforcement, training and facilities (Article 53). The law also authorises the CCG to expropriate civil organisations’ or individuals’ transportation, means of communication and space in order to protect maritime sovereign rights or to enforce the law (Article 54).

The law obviously targets foreign intervention. Article 21 states that, if foreign military or government vessels operating for non-commercial purposes violate Chinese laws and regulations in the waters under Chinese jurisdiction and they refuse to leave, the CCG authorities have the right to take measures such as deportation or enforced tugging. Article 47 allows the CCG to use hand-held firearms and other measures if foreign vessels enter China’s waters to conduct illegal operations and fail to comply with the CCG’s requests to board and conduct inspections. Under Article 48, the CCG is authorised to use shipborne or airborne firearms when handling ‘serious violent incidents’ at sea or countering attacks on law enforcement vessels or aircraft.

The final version of the law passed on 22 January gives the CCG more flexibility compared to the draft released in November 2020. For example, the draft of Article 72 explained that the term ‘jurisdictional waters’ includes the inland sea, territorial waters, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf—China’s so-called near sea that includes the Senkaku Islands, the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea. The explanation was removed in the final version, creating greater scope for the CCG to protect claims to sovereignty. In addition, Article 46 in the draft suggested that CCG should avoid aiming below vessels’ waterlines when using force, but those sentences do not appear in the final version.

These observations have several implications.

The CCG is China’s frontline force against foreign intervention in regional maritime disputes, including in the South China Sea and the Senkaku Islands. Its area of operations will now expand to include the Taiwan Strait. In 1988, Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping set the governing goal for the development of the navy, stating that, by 2020, China’s maritime interests would be secured by the navy’s capability to command the ‘near seas’ out to the second island chain. Now that the navy’s mission has moved beyond the first island chain, the CCG will be the main force for protecting China’s sovereignty within that area.

The CCG will enhance its capability under the framework of civil–military fusion and national defence mobilisation. Since the law provides the legal basis for the CCG to integrate political, military and civilian resources to support its development, strengthening cooperation with the military and the building of supporting facilities by local government could help with training CCG personnel in basic skills and the operations of larger CCG patrol vessels. Such developments would assist the CCG to resolve difficulties that it has faced in recent years.

The lack of a definition of ‘jurisdictional waters’ in the final version will increase the potential for conflict. In addition to creating opportunities for misunderstandings between foreign vessels and the CCG, it gives the coastguard flexibility to conduct law enforcement outside of its traditional jurisdictional waters.

As the new law shapes the strategic environment in the region, ASEAN needs to put such concerns into future negotiations on the code of conduct for the South China Sea. Regional countries should further analyse the procedures and actions of the CCG, including its cooperation with the Chinese navy in contingency and conflict scenarios, in order to enhance their rapid response capability. In addition, although Taiwan and Japan have put a lot of effort into strengthening Taiwan’s naval capability (the Taiwan Coast Guard’s largest patrol vessel, Chiayi (嘉義), which can land the Taiwanese navy’s S-70C helicopters and can be converted into a military vessel, was launched in June 2020), it’s also important for the US to undertake coastguard exchanges and to cooperate with regional allies in developing its Indo-Pacific strategy.

Vietnam assumed the chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations last November for 2020—perhaps the most challenging year ever to take on the role. The Covid-19 pandemic has changed the nature of diplomacy, particularly the somewhat old-fashioned style that ASEAN most favoured: frequent consultations, informal negotiations and confidence building through meetings and retreats—none of which are possible given the restrictions.

But an even greater challenge to ASEAN’s usual diplomatic style has been posed by the critical tensions between the United States and China. The growing competition jeopardises regional trade and economic cooperation and contributes to the sense of confrontation and unpredictability of international conduct. As both Washington and Beijing escalate the conflict and bilateral channels shrink, multilateral forums are becoming proxies for their disputes.

Vietnam has been preparing for the challenges and had been gearing up for this important year, when it not only chairs ASEAN but also serves as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council. It has already proved its ability to host important regional forums and even high-level meetings of global importance, such as the challenging US–North Korea summit in Hanoi last year—a remarkable makeover, given its relatively recent diplomatic isolation from which it only broke out with normalising relations with the US and joining ASEAN in the mid-1990s. But beyond merely holding the chair, many already harbour hopes that Vietnam can take a stronger leadership role within ASEAN.

ASEAN has lacked leadership for some time, which has led to hard questions about the group’s effectiveness.

The lack of a formal leader was a deliberate part of ASEAN’s design to ensure equality among a diverse group, but it became an inherent weakness. Indonesia is traditionally closest to such a position as de facto leader, but by virtue of size rather than by authority or legitimacy. But Jakarta’s notable withdrawal from that role since Joko Widodo became president leaves a leadership vacuum, even if informal. Many in ASEAN think that there could be no better country to stand up to the mounting challenges than Vietnam.

In fact, Vietnam’s impressive early response to Covid-19 has earned further respect and recognition from its neighbours, including much wealthier and more developed ones, like Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia. Economists from the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and Asian Development Bank predict that Vietnam has the highest chances in the region to come out of the post-coronavirus economic crisis in relatively better shape. This is a significant shift in Vietnam’s position in ASEAN, which, as a latecomer to the market economy, used to be labelled among the ‘second tier’ economies.

Diplomatically, Hanoi has also been taking on a more pivotal role. It is a de facto front-liner in South China Sea matters, where it has strong disputes with Beijing, but it’s also increasingly among the few that truly advocate for a powerful ASEAN role in regional matters. Hanoi’s leadership attaches strong importance to ASEAN norms and maintains a consistent foreign policy and has stepped up to socialise these norms to the other newer members. The stability of Vietnam’s government makes it unusual in a region that has recently seen many dramatic changes in national leadership.

Given the crisis enveloping the world, the main objective of Vietnam’s 2020 chairmanship is to preserve ASEAN’s unity and solidarity and prevent further erosion. The high expectations from the other ASEAN members and dialogue partners reflect a level of confidence in Vietnam’s diplomatic capability. Hanoi is strategically astute and aware of both the value and limitations of the regional body. But its commitment to the region’s security, and its unchanging posture on the South China Sea, show that Hanoi is keen to preserve ASEAN’s role in security and international affairs and to invest more diplomatic capital in the regional body.

Vietnam has been holding the line in the maritime disputes, at times rather diplomatically isolated in its determination from its Southeast Asian peers. But this year, it looks as if that has paid off. Hanoi shepherded a strong joint statement following the 36th ASEAN Summit, which openly reflected the tense situation in the region—a departure from ASEAN’s usual evasive statements on the matter. In his speech opening the summit, Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc called for ‘full and strict compliance’ with the rules in the South China Sea and said ASEAN was ‘making every effort to establish an effective’ code of conduct with China.

The joint statement expressed concerns about recent developments in the disputed waters, ‘which have eroded trust and confidence, increased tensions and may undermine peace, security and stability in the region’. It reiterated that the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is ‘the basis for determining maritime entitlements, sovereign rights, jurisdiction and legitimate interests over maritime zones’. Vietnam is also insistent that UNCLOS remains the basis for the negotiated code of conduct. All of that addresses China’s intensified military presence in the South China Sea and its repeated unilateral blockage of oil and gas exploration, as well as reports about Beijing’s intentions to announce an air defence identification zone.

Vietnam’s consistent South China Sea policy may have cost it some diplomatic points with China, as well as serious monetary losses from disrupted exploration projects in partnerships with international companies. But China’s overreach may have turned the tide, as the recent wave of formal complaints to the UN rejecting China’s excessive claims in the South China Sea indicates. In recent months, Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Australia and even the US have issued complaints that explicitly reject Beijing’s formal claim to offshore rights and sovereignty of the ‘Four Sha’ island groups—which is inconsistent with UNCLOS and the 2016 ruling by an arbitral tribunal in The Hague.

This will be considered in Hanoi as a sign of success in its policy of uncompromising internationalisation of the disputes and keeping the South China Sea a regional security issue, rather than a bilateral issue between China and individual Southeast Asian claimant states. By taking up this role when few ASEAN members wanted to, Vietnam has taken on a security leadership role, at least partially, in ASEAN. Not bad for a latecomer and certainly not an irrelevant contribution over 25 years of membership.

China appears to be accelerating its campaign to control the South China Sea and the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea. Beijing does itself no favours with the highly ambiguous nature of its claims in the region. Its internationally condemned ‘nine-dash line’ sometimes appears to be delineating its claims to the island features within it. More ominously, Beijing sometimes insinuates the line as a maritime delineation, carving out sovereign control of the sea itself as well as the airspace above it.

China’s ongoing militarisation of many artificial features in disputed waters is well known. A less well known, but highly consequential implication of this militarisation is the vastly increased capacity it gives China to project power not only to control the reefs and rocks of the South China Sea, but, in the future, to assert control over the high seas and airspace above it. Beijing is vocal about its opposition to innocent passage and other military activities within its 200-nautical mile exclusive economic zones.

Beijing has tried hard to keep its dispute resolution efforts focused on bilateral negotiations between itself and the various claimants, effectively fracturing a united response by ASEAN. Pushback in the region is only now beginning. China’s sweeping claims also impact many countries that lie far beyond the shores of the South China Sea. The US, Japan, Australia, India and many others around the world have critical interests in using the sea directly for economic, scientific and military purposes. More urgently, maintaining an open and free system of movement through the high seas—and in the future, in outer space—is of critical importance.

The decisive rejection of China’s claims in the South China Sea by an arbitral tribunal under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea in 2016 only accelerated Beijing’s continued bad-faith efforts to construct features, militarise them, and extend administrative control over others’ presence and activities to the furthest reaches of the nine-dash line. In fact, the ruling decisively rejects both China’s claims to many rocks and maritime features and the idea that these islands can generate territorial seas and exclusive economic zones.

This studied strategic ambiguity by China (on display on other fronts as well) should encourage the international community to confront an alternative and altogether darker explanation for Beijing’s behaviour—that it is building forces and positions in the region so that over the long term it can assert sovereign authority over the South China Sea.

This interpretation of China’s actions, though difficult to accept, should be considered as a possibility in military and strategic planning efforts around the world with an eye towards avoiding this worst-case outcome. It is important to remember that the scope and scale of China’s claims are unprecedented in international law and have no real analogue anywhere else on earth. An unwillingness to confront this scenario risks ceding Beijing permanent control over economic and military activities over a large and critical section of the world’s oceans—and beyond.

The South China Sea is a third larger than the Mediterranean Sea and more than twice as large as the Gulf of Mexico. Acknowledging China’s sweeping claims to sovereignty over this massive space would increase the possibility of a future international environment in which ever larger portions of the global commons are cut off and controlled by individual nations.

Either the international community believes in maintaining a free and open global commons and protects international law or it doesn’t. If it doesn’t, then China’s potential annexation of this vast space will guarantee similar claims over the world’s oceans. To foreclose on this future will require an active and aggressive response by the widest grouping of states possible. Regardless of how individual claims over the various land features in the South China Sea are resolved, the entire globe has a stake in free and open access to the region.

For this reason, the US, along with all major allies and partners, should explicitly link China’s own access to the global commons with its behaviour in the South China Sea. Washington’s announcement of its rejection of Beijing’s maritime claims, underscored by the US Navy dual aircraft carrier strike group exercises in the region, is a good beginning. However, operations in the South China Sea play to China’s strengths. The US and the widest range of allies and partners in the international community should begin to articulate and apply escalating administrative and technical restrictions globally on Chinese shipping, air travel and transport in and through exclusive economic zones around the world by participating countries.

Restrictions on economic and military transit and scientific exploration should be pre-planned and scalable so that they are similar to Chinese moves in the South China Sea. These allied ‘grey zone’ competitive activities could be problematic for Beijing; they would drastically increase the cost and complication of accessing the Indo-Pacific region and beyond. For example, contiguous US, Japanese and Philippine zones restrict direct Chinese access to the Western Pacific. This possibility should be communicated to Beijing should it attempt to assert sovereign control in the South China Sea through force.

Securing the highest degree of freedom and access throughout the global commons should be the ultimate goal of this international effort. Focused and reciprocal restrictions on China throughout the exclusive economic zones of the world should be coupled with strong assurances that they remain open for participating nations. Moreover, these restrictions on China should be easily and quickly reversible. When Beijing comes to its senses on the use of the South China Sea, its access to the global maritime commons should be both restored and encouraged.

Although this strategic approach to countering Beijing’s most aggressive designs in the South China Sea appears to be rather drastic, like-minded nations around the world should be prepared to deliver a decisive shock to Beijing’s calculations about any gains it may achieve by limiting access to the South China Sea and rejecting the free use of the global commons more generally. Even hinting that a global response on this scale is possible should concentrate minds in Beijing on their strong and growing dependence on the global commons to reach their much vaunted ‘centenary goals’. Together, allied nations should encourage China to support an open and free global commons today in the South China Sea.

When the Cold War ended, many pundits anticipated a new era in which geoeconomics would determine geopolitics. As economic integration progressed, they predicted, the rules-based order would take root globally. Countries would comply with international law or incur high costs.

Today, such optimism looks more than a little naive. Even as the international legal system has ostensibly grown increasingly robust—underpinned, for example, by United Nations conventions, global accords like the 2015 Paris climate agreement, and the International Criminal Court—the rule of force has continued to trump the rule of law. Perhaps no country has taken more advantage of this state of affairs than China.

Consider China’s dam projects in the Mekong River, which flows from the Chinese-controlled Tibetan Plateau to the South China Sea, through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. By building 11 mega-dams near the border of the Tibetan Plateau, just before the river crosses into Southeast Asia, China has irreparably damaged the river system and wreaked broader environmental havoc, including saltwater intrusion in the Mekong Delta that has caused the delta to retreat.

Today, the Mekong is running at its lowest level in 100 years, and droughts are intensifying in downriver countries. This gives China powerful leverage over its neighbours. And yet China has faced no consequences for its weaponisation of the Mekong’s waters. It should thus be no surprise that the country is building or planning at least eight more mega-dams on the river.

China’s actions in the South China Sea may be even more brazen. This month marks the sixth anniversary of the country’s launch of a massive land-reclamation program in the highly strategic corridor, which connects the Indian and Pacific oceans. By constructing and militarising artificial islands, China has redrawn the region’s geopolitical map without firing a shot—or incurring any international costs.

In July 2016, an international arbitral tribunal set up by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague ruled that China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea lacked legitimacy under international law. But China’s leaders simply disregarded the ruling, calling it a ‘farce’. Unless something changes, the US-led plan to establish a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ will remain little more than a paper vision.

China’s open contempt for the tribunal’s ruling stood in sharp contrast with India’s response to a 2014 ruling awarding Bangladesh nearly 80% of 25,602 square kilometres of disputed territory in the Bay of Bengal. Although the decision was split (unlike the South China Sea tribunal’s unanimous verdict) and included obvious flaws—it left a sizeable ‘grey area’ in the bay—India accepted it readily.

In fact, between 2013 and 2016—while the Philippines-initiated proceedings on China’s claims in the South China Sea were underway—three different tribunals ruled against India in disputes with Bangladesh, Italy and Pakistan. India complied with all of them.

The implication is clear: for large and influential countries, respecting the rules-based order is a choice—one that China, with its regime’s particular character, is unwilling to make. Against this background, Vietnam’s possible legal action on its own territorial disputes with China—which has been interfering in Vietnam’s longstanding oil and gas activities within its exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea—is unlikely to amount to much. Vietnam knows that China will ignore any ruling against it and use its trade leverage to punish its less powerful neighbour.

That is why an enforcement mechanism for international law is so badly needed. Disputes between states will always arise. Peace demands mechanisms for resolving them fairly and effectively, and reinforcing respect for existing frontiers.

Yet such a mechanism seems unlikely to emerge anytime soon. After all, China isn’t alone in violating international law with impunity: its fellow permanent members of the UN Security Council—France, Russia, the UK and the US—have all done so. These are the very countries that the UN charter entrusted with upholding international peace and security.

Nowadays, international law is powerful against the powerless, and powerless against the powerful. Despite tectonic shifts in the economy, geopolitics and the environment, this seems set to remain true, with the mightiest states using international law to impose their will on their weaker counterparts, while ignoring it themselves. As long as this is true, a rules-based global order will remain a fig leaf for the forcible pursuit of national interests.

The United States military hasn’t conducted a single combat operation within the sprawling area of responsibility that defines the Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) in 44 years. I’m overly fond of pointing out this little-commented-on fact of Indo-Pacific security, because its significance is underappreciated.

The last US combat operation in the region was in Cambodia, in May 1975, against the newly victorious Khmer Rouge, which had recently captured an American-flagged merchant ship, the SS Mayaguez. The forceful US response was a spasmodic demonstration of resolve: a coda to Washington’s humiliating abandonment of South Vietnam and precursor to a more ‘offshore’, less interventionist Pacific posture.

Since then, US forces haven’t engaged in combat anywhere in the western Pacific, in spite of many crises and reactive deployments to the region’s numerous flashpoints, such as the Taiwan Strait, the Korean peninsula and the South China Sea. Afghanistan falls within the area of responsibility of US Central Command (CENTCOM).

This situation held throughout the so-called unipolar moment, including the post-9/11 high-water mark of US global military activism, when Southeast Asia was labelled as a second front in the ‘war on terror’. US forces provided non-combat counterterrorism support to Philippine forces, but exercised greater restraint than in other US combatant commands.

In fact, US forces have seen more recent action in Europe than they have in the Indo-Pacific. The 2011 special forces raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound, at Abbottabad in Pakistan, fell technically within PACOM’s area of responsibility. But that was a sui generis spillover from CENTCOM.

Empirically, the absence of armed intervention appears at odds with Asia’s persistent security crises, nationalist fault lines and substantial investments in modern military power. The contrast sharpens after factoring in that America’s bloodiest post-1945 military interventions were in Korea and Vietnam.

A reasonable conclusion might be that deterrence has successfully maintained the peace in Asia, especially East Asia, underpinned by US forward-deployed combat forces and intelligence-gathering capabilities. The US presence bought time for post-colonial states to achieve internal stability, while deterring external adventurism and providing sufficient forewarning of hostile intentions so that crises could be contained below boiling point.

But that sounded much more convincing 10 years ago than it does today. In the intervening decade, North Korea has sunk a South Korean warship, shelled South Korean civilians and gatecrashed into the thermonuclear intercontinental ballistic missile club—all without incurring a single retaliatory US shot.

In the South China Sea, the US stood by as China transformed disputed specks into artificial bases that today support military and paramilitary forward operations, incrementally intimidating Southeast Asian states into submission. In 2012, the US didn’t intervene when China wrested control over the Scarborough Shoal from the Philippines, another US treaty ally.

Today, Vietnam appears isolated within ASEAN, as a lone source of resistance to China’s ongoing encroachments in the South China Sea. US freedom-of-navigation operations have done nothing to reverse this creeping expansionism, although belated US deterrent signalling appeared to dissuade China from constructing another artificial island base at Scarborough Shoal.

We tend to think of China’s ‘grey zone’ tactics in the South and East China Seas, and North Korea’s asymmetric provocations as somehow novel. But China and North Korea are both seasoned exponents of hybrid warfare. What has changed is the intensity and sophistication of such tactics, which are now reaping strategic effects.

US abstention from using force in the western Pacific undoubtedly owes something to successful deterrence. Far less widely understood is that the threshold for using armed force in Asia is higher than in most other regions. The existence of nuclear weapons in South and Northeast Asia is one factor in this, but not the whole explanation.

The India–Pakistan strategic dynamic is perhaps an outlier in this respect, underlined by the Balakot airstrike and aerial encounters that took place earlier this year. North and South Korea have also traded blows, despite the existence of nuclear weapons on the peninsula. One big difference, however, is that US credibility is directly on the line in East Asia—combat forces are present in Japan and South Korea, and Washington’s extended nuclear deterrence guarantees apply to Seoul, Tokyo and Canberra.

In reality, the US military has trodden, flown and swum rather carefully in the western Pacific since the Vietnam War, not only because peace has largely prevailed but because the risks of war with North Korea and China are perceived to be very high.

This forbearance is essential to understanding why INDOPACOM’s area of responsibility hasn’t experienced a single US combat operation in nearly half a century. Imagine North Korea relocated to North Africa and China’s South China Sea artificial bases transposed to the Persian Gulf, and see if you get the same results.

It flows from this that military entrapment is overestimated as a strategic risk among US treaty allies and close partners in Asia, and abandonment is probably underestimated. While it would be unwise to underestimate the resolve of the US, particularly if its armed forces, territory or citizens were directly attacked, the historical record suggests that the bar for US military intervention in the Indo-Pacific region is significantly higher than many observers think, even in defence of allies.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not urging the US to undertake another Mayaguez operation in order to reassure jittery allies and deliver a slice of shock and awe to deter emboldened adversaries in the region. The US military has amassed plenty of combat experience elsewhere in recent decades. Too much of the wrong kind, perhaps, but it still counts in the mix.

By the same token, it’s worth remembering that China has more recent experience of fighting a conventional war in East Asia than America. Given this, it’s fortunate that no country in the region has a particularly fond memory of its most recent war—not China, not Japan, not the Koreas, and not Vietnam.

If that has helped to raise the threshold for war, it also lends a symbolic, demonstrative aspect to the next state-on-state conflict. Wherever and however it breaks out, everyone will be watching, and it will be more important than ever not to end up as the losing side. Once the Rubicon of armed combat has been crossed, even inadvertently, substantial escalatory pressures could come into play from leaders unwilling to wear the political consequences of defeat. One particularly thinks of China in this regard.

Arguably, the absence of recent combat experience in the region will reinforce caution among the region’s revisionist powers and a preference for challenging the status quo below the threshold of armed conflict. However, the strategic pickings available from grey-zone tactics are growing thinner, now that the US and regional countries are latterly waking up to the fact that warfare was never permanently banished from the region. It just took on other guises.

Two millennia of history is no guide to the next two decades. But it can help to provide a broader perspective, in this case on China and its relationship with its southern maritime neighbours.

Much of this history has been overlooked by Eurocentrists, for whom history begins in the 16th century; by those whose histories focus on anti-colonialism and nation-building; and by Sinocentrists, who see China’s neighbours as more or less tributary.

Usually forgotten, too, is that the maritime region—the whole archipelago and peninsula—has a common Austronesian linguistic and cultural identity. This region, sometimes referred to as Nusantaria, now has some 400 million people and in principle commands the major straits, including Malacca, Lombok and Sunda.

The region has always been key to east–west commerce—west, in this case, being India, Persia and Arabia before Europe entered the scene. For almost all of the two millennia, traders from China played only a minor part; foreigners went to China because of its market. From the 18th century, Chinese migrant traders played an increasing role but were never dominant. Nor are they today in international commerce, which remains, as ever, dependent on ships and not on high-cost journeys over mountains and deserts—the over-rated Silk Road.

The first known direct contact between imperial Rome and China was not over land but by ship. Romans arrived in Nusantaria by sea in the second and third centuries, when Rome had massive trade based out of Alexandria with India, which in turn was linked by traders and Hindu and Buddhist preachers with the archipelago. Chinese goods reached India and beyond via the archipelago or the Kra isthmus. Chinese monks visited Sumatra, where Buddhism was thriving, but the traders and sailors were not Chinese. Fast-forward to the Tang dynasty, which lasted from the 600s to the early 900s, and whose prosperity led to a surge in trade. Guangzhou was a trading hub to which came Malays, Arabs, Tamils and others. The Chinese stayed home to make their money from the domestic market.

Chinese traders began to play a role from the late Song dynasty (960–1279) onward but were never predominant. The first Chinese communities that permanently settled in Nusantaria appear to have been those left behind by Kublai Khan’s failed invasion of Java. The Yuan emperor tried to force King Kertanegara to accept his overlordship. A huge invasion fleet should have overwhelmed the Javanese, but, tricked and ambushed, the invaders had no time to finish the job before the seasonal wind change and a lack of supplies forced them to leave. Asymmetric war won.

The next effort to spread Chinese power was the seven Ming voyages under Zheng He with his huge fleets in the early 1400s. He persuaded several minor states to acknowledge the emperor’s supremacy. But it was a short-lived power projection—30 years—because it cost too much with scant return. China was a giant compared with the coastal states of the archipelago and India, but fragmentation was a disadvantage for a centralising land-based power. The Srivijayan and Majapahit empires, on the other hand, thrived by being loosely organised and trade based.

A mythology has grown up over the size of Zheng’s ships and his navigational achievements. The voyages were made a thousand years after Asian Austronesians began to colonise Madagascar. The Portuguese, who arrived at Melaka only 75 years after Zheng, viewed the Javanese as the region’s leading navigators with the largest ships they had ever seen.

Another convenient (for China) myth is that states from the archipelago were ‘tributary’ to China. Tribute was mostly an exchange of goods, or a tax for the right to trade. Chinese merchants often had to pay tribute to local rulers if they wanted to trade at a port in the archipelago.

Over time, European commercial imperialism undermined the power and trade wealth of the various sultanates. Europeans made the trade rules and created demand for labour for mines and plantations, which brought huge numbers of Chinese and spurred the rapid growth of regional trade with southern China. That, in turn, led to the emergence of an ethnic Chinese business class. But the demographics that partly drove the shifts in the 19th and 20th centuries are reversing as China’s population declines while the populations of the countries of maritime Southeast Asia grow.

China’s need for large-scale foreign trade is a very recent phenomenon. It only started about three decades ago, and a shift back to self-reliance has already begun. As in the past, threats to China are more likely to come from its overextended western and northern land borders.

Meanwhile, China’s recent expansion in the South China Sea has sparked a reawakening of pan-Malay sentiment. Even the Philippines, so long forced by Spain and the United States to look across the Pacific, is refocusing. Obsessions with Pakistan and Kashmir remain an impediment to India’s reorientation, but in India’s port cities there’s the potential for reinvigorating historical trading links to the archipelago, as well as Persia and Arabia. ASEAN can barely paper over the interest gap between its naturally more vulnerable mainland member states and the maritime ones, which include once-Austronesian Vietnam (Champa).

China’s plan to influence politics and trade through the Belt and Road Initiative seems likely to produce many projects that have little economic justification or that, like the Tanzam railway in Africa, quickly decay. The BRI comes at a time when transcontinental trade shows signs of stalling and growth prospects lie more in smaller ports that serve regional traffic, particularly in the archipelago but also in India, with its long, two-faced coastline. China’s accumulated capital in the region is small compared with the investments made by Japan and the West, and its surpluses for foreign investment are shrinking. Equalling the US in some fields of technology—as the Soviets did during the Cold War—is of limited relevance.

In short, there’s little basis in history or economics for Chinese hegemony over the southern maritime region of Asia (the Nanyang), however much it militarises the seas. The cost in money and relationships will be too high as the Chinese Communist Party dynasty and its people age.

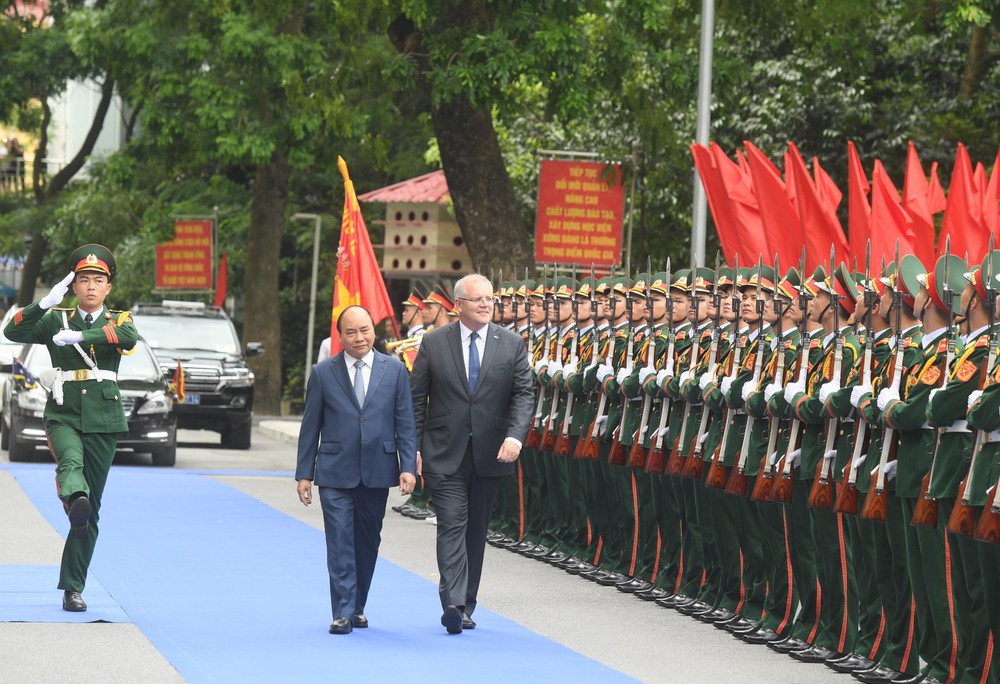

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has just completed an official visit to Vietnam—a strategic partner and a priority country for Australia’s regional relations. Indeed, bilateral relations have been going from strength to strength and are likely to continue to broaden and prosper.

The visit resulted in commitments to bolster economic ties as well as support for the multilateral trading system and working towards completing the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. People-to-people ties will be boosted by expanding Australia’s work and holiday visa quota for Vietnamese nationals from 200 to 1,500 per year.

The two countries also committed to strengthening collaboration in knowledge and innovation and leadership training by establishing a Vietnam–Australia centre at the Ho Chi Minh National Academy of Politics in Hanoi. Morrison visited the mobile field hospital that will soon form part of Vietnam’s continuing contribution to the UN peacekeeping mission in South Sudan. Australia has been playing a key supportive role in Hanoi’s contribution there, a highlight in recent bilateral ties.

Reviewing their strategic partnership, Hanoi and Canberra agreed on a plan of action for the period 2020–2023 that will focus on three priority areas: enhancing economic engagement; deepening strategic, defence and security cooperation; and building knowledge and innovation partnerships.

These are all very positive developments and welcomed on both sides.

But the timing of Morrison’s visit put the spotlight on another issue—one that goes beyond just bilateral relations.

The Chinese survey ship Haiyang Dizhi 8 and its maritime militia and coastguard escorts have been a fixture in Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone around the Vanguard Bank in the South China Sea since early July. The survey ship briefly left the area and then returned, moving even closer to Vietnam’s shores. The US State Department issued a second statement following the return of the vessel, explicitly condemning China’s actions and supporting Vietnam’s longstanding oil and gas extraction and exploration activities in the area.

The gravity of the incident hasn’t been fully appreciated around the world, and Hanoi has been hoping for more diplomatic support from the international community.

Prior to Morrison’s visit, Foreign Minister Marise Payne signed a joint statement of the Australia–Japan–US strategic dialogue with her counterparts Mike Pompeo and Taro Kono, and the issue was also mentioned in the joint statement from the AUSMIN meeting earlier this month in Sydney. In both statements the parties expressed concern over disruptive activities in relation to longstanding oil and gas projects in the South China Sea. But Vietnam hoped for stronger language from Australia during Morrison’s visit.

While land reclamation and militarisation, freedom of navigation, and even the future of the ASEAN-developed code of conduct were discussed during the visit, Morrison avoided naming the incident around the Vanguard Bank and calling out Beijing’s actions. At a press conference in Hanoi he was asked explicitly about the need to do so, but referred to principles of international law instead.

Morrison declined to take sides and instead drew a vision of an Indo-Pacific where sovereignty and independence are respected and no country suffers from coercion from another. When pressed to specify exactly what type of coercion he was referring to, the prime minister defined it as ‘any impingement on their own sovereignty and independence that would prevent them in any way from pursuing lawfully what is their objective’.

Morrison’s careful tiptoeing around the issue is not out of step with the inclination of other ASEAN states, for example, which feel frequent pressure from Beijing not to speak up about South China Sea matters. It was a deliberate effort not to name China, which seems odd given both the timing of the trip and Australia’s vocal defence of the rules-based order. For this first official bilateral visit from a sitting Australian prime minister to Vietnam in 25 years, Morrison’s performance was rather underwhelming.

Besides the carefully worded official statements, the visit served the purpose of encouraging Hanoi to continue to stand up to China. Morrison is right in recognising Vietnam’s strategic importance and is right not to make the visit about China only. But while stressing the upgrading of the relationship from one of ‘friends’ to ‘mates’, his reticence may also be signalling that his government will be even more hesitant to call out China over its activities in the South China Sea.

The Haiyang Dizhi 8’s incursion into Vietnam’s EEZ has international ramifications. This isn’t an incident that has happened in isolation, and a muted international response will only reinforce what Beijing is looking for—a gradual but consistent normalisation of its actions that helps it achieve control of the South China Sea. In fact, the level of Beijing’s activities in the area has been abnormally high in recent times. Along with the Vanguard Bank situation, there have been missile tests, military exercises, warships sent to the Philippines, survey vessel activity, and frequent harassment of fishermen throughout the region.

While smart diplomacy requires Canberra to carefully consider its statements as its voice becomes more consequential in the era of tense great-power competition, it also needs to work out a balance between speaking out and deftly side-stepping difficult issues. Effective diplomacy includes speaking up when necessary.