The fall of Singapore: the lessons of alliance failure

Most of us would agree that the Fall of Singapore in February 1942 remains the biggest strategic shock Australia has ever received, but we pay too little attention to why it was such a shock, and what we can learn from it.

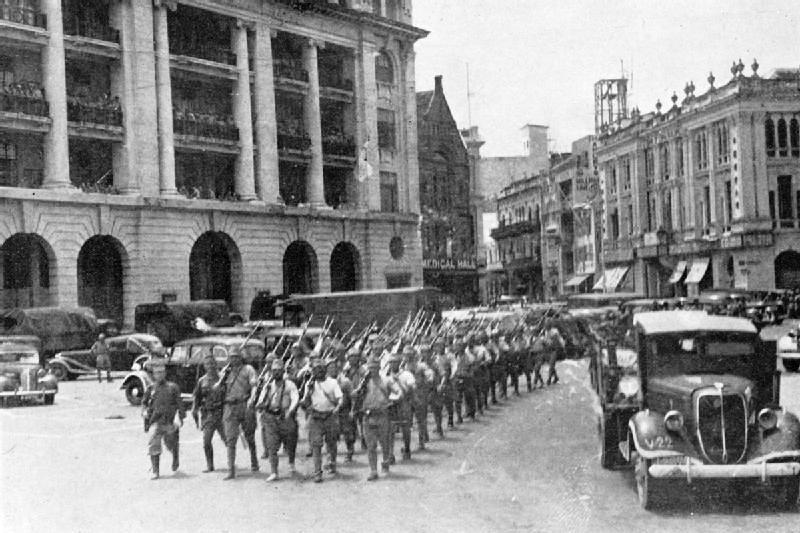

The humiliatingly easy defeat of the island’s defences by the Japanese was of course a catastrophic military failure, with grave consequences for those whom it engulfed. But the island and its base had little strategic significance to Australia when there were pitifully few ships and aircraft to operate from it. The real strategic shock was not that Singapore fell, but that it was useless because Britain could not commit forces to operate from it strong enough to have any chance of contesting Japan’s ability to project power around the Western Pacific.

This was a quintessential failure of an alliance, and of a strategic policy based on alliances. It marked a whole generation of Australians and profoundly shaped our strategic thinking for decades. And it carries important lessons for us today.

The seeds of the disaster were planted long before 1942. The British naval power in Asia which had guaranteed Australia’s security since the First Fleet was already falling sharply before the First World War, and fell even further after it. Unable to maintain a major battle fleet in the Pacific, Whitehall planned to meet any threat by sending the main fleet from Britain to the base at Singapore.

But it was always obvious that this would not be possible if Britain faced a simultaneous threat in Europe, and though the 1930s the risk of simultaneous crises with Germany and Japan plainly grew. Nonetheless, Australians persuaded themselves to depend for their defence from Japan on Britain’s ability to send massive air and naval forces to Singapore if and when they were needed.

When the time came, Britain’s air and naval forces were utterly committed to defending Britain itself, and to an intense maritime struggle for control of the Mediterranean on which its entire strategy for holding Germany depended. No one can blame British leaders for giving these commitments priority. They made the right decision for Britain.

The blame lies with Australian leaders for erecting Australia’s strategic policy on such flimsy foundations. In their defence they could cite Whitehall’s frequent assurances that the fleet would be sent if it were needed, but they knew those assurances meant nothing if there was war in Europe. And yet they clung to them as the danger of concurrent wars in Europe and Asia quite plainly grew. This was a massive failure of strategic policy.

At the heart of this failure was an inability to recognise and accept fundamental shifts in the distribution of wealth and power which were transforming both the global and the regional strategic orders, and undercutting Britain’s place in them. Britain with its world-wide commitments simply could not match Japan’s strategic weight in Asia any more.

These shifts had been underway for decades, and had been perfectly well understood by an earlier generation of leaders like Alfred Deakin. But the men of the 1930s lacked the insight and perhaps the courage to see what was happening and what should be done about it. In part no doubt that was because they simply couldn’t imagine what the alternatives might be. What else could Australia have done except rely on the Royal Navy?

It is a question which even now deserves attention. Was there a policy Australia could have adopted that would have lessened our dependence on Britain and allowed us to defend ourselves against Japan? John Curtin thought there might: as Labor leader in the late 1930s he suggested that an independent force of aircraft and submarines might be able to keep Japanese forces from our shores.

He may have been right, but this kind of independent strategic posture would have required not just massive investments but a shift in national outlook and even identity which most Australians could not encompass, and which most leaders were not prepared to consider. Perhaps by the late 1930s it was already too late anyway.

Of course as prime minister in late 1941 Curtin did find another alternative—turning to America, which thankfully worked well for a while. But the experience of alliance failure haunted those who had lived through 1942. The lesson that no ally, no matter how deeply connected by shared values and history, can be relied upon when the crunch comes shaped both the Forward Defence posture of the post-war decades and the Self-Reliance policy which followed.

Only in the last twenty years has that lesson been forgotten. Since about 1996, and especially since the mid-2000s, Australian political leaders on both sides of the aisle have become sublimely confident that Australia’s security can be entrusted to the care of our principal ally. Few now suggest that Australia might need to defend itself and its most vital interests independently.

And this is despite the fact, so obvious but so seldom acknowledged, that that the fundamental distribution of wealth and power has been shifting rapidly against the United States. Today, relative to its Asian rivals, America is weaker economically, diplomatically and militarily than it has been since World War Two, and yet we rely on it more. The parallels with the years before Singapore are all too obvious.

So the Fall of Singapore holds a vital lesson for us: that alliances can and do fail, and that any strategic policy that does not give that reality due weight is likely to fail too. The question, of course, as it was in the 1930s, is: what’s the alternative? That is the question we should be addressing much more seriously. There are answers to be found, but they are not easy ones.