Anticipating what Trump wants, Taiwan puts money in America first

Taiwan’s President Lai Ching-te must have been on his toes. The island’s trade and defence policy has snapped into a new direction since US President Donald Trump took office in January.

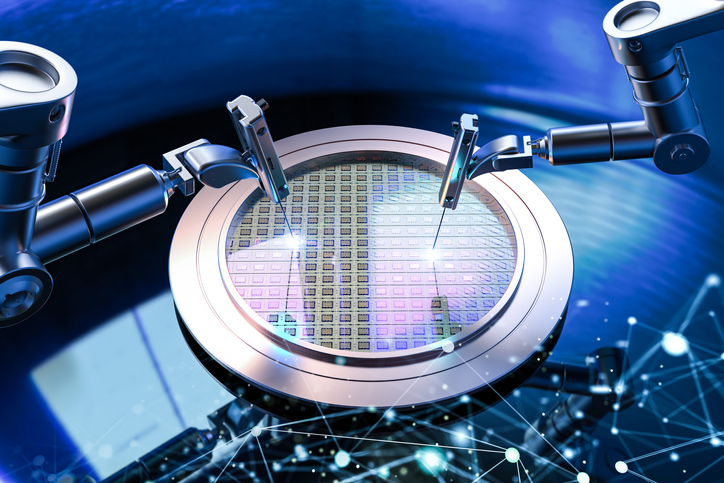

The government was almost certainly behind a deft move by the country’s giant semiconductor company, TSMC, to set up three production facilities in the United States. Also, Lai’s administration has stepped up plans to import the kinds of US products that would catch Trump’s eye. It’s pushing for a hefty rise in defence spending, too.

Anyone would think that Taiwan had done its homework and was ready for the new US administration. Or maybe it’s just faster on its feet than most. Senior Taiwanese officials have been carefully studying Trump’s agenda and looking for items they can enthusiastically support and that advance Taiwan’s interests.

Take TSMC’s announcement in early March that it was sinking US$100 billion into the US to build the chip plants, along with a research and development centre, bringing its total pledged investments in the US to US$165 billion. This came after Trump accused Taiwan of stealing the US’s chip business on the campaign trail and threatened a 100 percent tariff on chips.

In Taiwan, there was an uproar. Many Taiwanese believe TSMC, which makes at least 80 percent of the world’s most advanced chips in Taiwan, is a ‘silicon shield’. They see it as crucial for Taiwan’s geopolitical protection as it gives foreign countries an incentive to protect the country. There were worries that if Lai went along with Trump’s push to reclaim the world’s chip industry for the US, the silicon shield would be weakened.

But Lai understood that, if he appeared to be obstructing Trump’s agenda, diplomatically isolated Taiwan might be discarded. Had Trump not won the US election, TSMC probably would not have announced such a large investment. But the gamble paid off. On the day of the announcement of the deal, Trump appeared happy.

‘I would say it came off as an extraordinary success,’ Chris Miller, author of Chip War and a world expert on the semiconductor industry said at a seminar in Taipei in late March.

‘TSMC managed to put itself in a position of a partnership with the new administration,’ Miller said. ‘All these are wins for TSMC and wins for the U.S.-Taiwan relationship as well.’

‘I don’t think the TSMC announcement solves every issue. But it does put the relationship on a much stronger footing.’

Taiwan’s chip industry is unlikely to see significant changes in the next five years. Building plants in America is a sluggish process. Many experts also reckon TSMC is born of a unique industrial and cultural ecosystem in Taiwan that will be extremely hard to uproot and duplicate in the US.

Lai’s moves don’t stop with chips. He also has plans to buy natural gas from Alaska, announced as early as February. Taiwan historically has one of the strongest environmental movements in Asia and most Taiwanese are highly conscientious about conservation. But Lai and his officials noted Trump’s plans to expand the oil and gas industry.

They also noted Trump believes trade deficits are a threat to the US economy. Lai and his team pragmatically hope the procurements will help reduce the US’s deficit with Taiwan, which in 2024 was its sixth largest, and that this will also help with Taiwan’s energy security.

Currently Australia, Qatar and the US are the three largest suppliers of natural gas to Taiwan, with the US supplying 10 percent. When the Alaskan deal eventuates, it’s highly likely that Taiwan will prefer to reduce imports from Qatar, as it will be unwilling to alienate Australia for strategic reasons.

Then, Lai also moved quickly with plans to buy US agricultural products. Taiwan’s foreign minister announced in late March that Taiwan would send a procurement mission to the US this September. Lai has also promised to push the defence budget to more than 3 percent of GDP this year, up from the planned 2.45 percent.

Of course, Lai’s battle is far from over. The Trump administration is highly unlikely to be content with that level of defence spending and will push Taiwan to spend 5 percent or even 8 percent of its GDP on defending itself. And on 2 April, Trump announced a new wave of tariffs in the US’s most aggressive trade action in nearly a century. Among them was a 32 percent tariff on goods from Taiwan, exempting semiconductors. Outraged Taiwanese officials are protesting. Miller says he expects much more friction and a lot of ‘hard-elbowed’ diplomacy between Taiwan and the US for the next four years.

But Taiwan notably proposes no retaliatory tariffs. Lai is obviously still focused on good relations with Trump.

These early moves say a lot about Lai’s leadership style. He and his independence-minded Democratic Progressive Party have revealed a strong pragmatic streak. Lai has also shown he is able to put himself in the minds of Trump and his supporters and anticipate what pleases them.