Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Since 2013, when rumours first began to circulate in the US mainstream media that Russia might have violated the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, analysts have been trying to clarify the nature of the breach and identify the particular missile system involved. To date this has proved an exercise as difficult as the fabled hunting of the snark. Over two years later, and notwithstanding two formal ‘findings’ by the US in its annual compliance reports that Russia is in violation of the treaty, both arms control specialists and the broader public remain mystified about what is supposed to have happened. In this post, I want to explore what we know. And let me warn readers in advance that we don’t know much.

Early reports seemed to suggest that the Russians were working on a new intermediate-range ballistic missile, which they had—apparently—cunningly disguised as an intercontinental ballistic missile. In reality, that was never much of a claim. ICBMs are already caught and limited by the START treaty. And as Stephen Pifer of Brookings noted back in July 2013, it’s not a violation of the INF treaty for a signatory to test a strategic-range ballistic missile system at a shorter range: weapons are defined by their maximum range. Still, the story grew that Russia was violating the INF treaty through its development and testing of the RS-26 ballistic missile.

In late January 2014, that story was overtaken by a second: Michael Gordon reported in the New York Times that concern centred upon the testing of a new ground-launched cruise missile and that earlier speculation about an ICBM flown to shorter-range had caused analysts to fixate upon the wrong system. The hunt began anew—for a Russian cruise missile system that might fit the bill. Towards the end of April 2014, Jeffrey Lewis produced a column in Foreign Policy that examined the possibility Russia might be in violation of the INF treaty either through its RS-26 ‘intermediate-range ICBM’ (to use Lewis’ phraseology) or through its R500, a cruise missile devised for the Iskander weapon system. Part of the problem, Lewis observed, lay in trying to define the range of a missile that could easily use a quarter of its flight-time zigzagging from side to side.

On 29 July 2014, the US State Department noted publicly in its annual report on arms control compliance that the US believed Russia was in violation of the INF treaty, specifically the provisions prohibiting possession, production or flight-testing of a ground-launched cruise missile with a range capability of 500-5,500 kilometres, or the possession or production of launchers of such missiles.

On 30 July 2014, in a piece for the Federation of American Scientists, Hans Kristensen covered the finding, pondering why it had taken so long to call as a violation a system first tested in 2007. He believed the culprit was the R500 cruise missile. An analysis for CSIS in October 2014 by Paul Schwartz identified the concerns about the RS-26, but focused primarily upon the R500 as the weapon most likely to be behind the violation.

The State Department’s 2015 annual report on compliance, issued on 5 June, noted that Russia continued to be in violation of the INF treaty. The report included a rather dry section on compliance analysis which seemed to imply that the violation related to flight-testing of a cruise missile from a land-based launcher that was not ‘fixed’, ‘used solely for test purposes’ and ‘distinguishable’ from GLCM launchers. A piece by Pavel Podvig published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists on 22 June 2015 started to home in on the possibility of a flight-test violation in relation to a cruise missile typically not deployed in a land-based mode. Podvig believed a long-range submarine-launched cruise missile had been tested without due regard to launcher type.

Subsequently, on 23 June, Rose Gottemoeller’s Interfax interview carried a few more clues. The US had been discussing this issue with Russia since May 2013, she said. Asked for specifics about the alleged violation, Gottemoeller said the R500 was not the missile involved. Nor was the RS-26. She said at issue was a ground-launched cruise missile with a range of 500-5,500Km and the US government was confident that Russia knew which missile was meant.

Gottemoeller’s interview has not entirely stopped analysts from arguing the case against the RS-26 and R500—see here and here for examples. But on 1 July 2015, following the Gottemoeller interview, a blogger on the Nuclear Diner rehearsed the Podvig logic as now offering the most plausible case. Jeffrey Lewis at Arms Control Wonk seems to be headed down a similar track, posting a piece by Nikolai Sokov on Russian cruise missiles. Sokov believed that the allegation centred upon a land-based test of a sea-launched cruise missile, the SS-N-30A, known as the Kalibr.

While some might wonder about the utility of the INF treaty—given it doesn’t constrain sea-launched or air-launched intermediate-range missiles—the compliance of signatories is an important issue in its own right. In retrospect, the case against Russia has been blurred by Washington’s unwillingness to provide greater initial detail of the alleged violation. Even now, it’s not clear what actually occurred. We might finally be gaining a better understanding of the problem. But arms control shouldn’t be a guessing game.

When Chinese prime minister Wen Jiabao participated in the founding meeting of the Central and Eastern European (CEE)–China Summit in Warsaw April 2012, it seemed few in Canberra asked why Poland was chosen by China as the leader of the grouping. With a population of 38 million citizens (the sixth largest European Union member) and an impressive economic performance of 2–3% GDP growth during the global financial crisis, Poland is surely a formidable European player. But the Chinese instinctively understand what many still do not: if a new leader in the European Union (EU) is to emerge, Poland is a safe bet. What can Polish leadership do for international security? And how can Polish interests dovetail with Australia’s?

In less than a decade Poland fought its way through to the very forefront of EU’s foreign policy. It has fostered greater EU engagement in its Eastern neighbourhood, called for energy solidarity to reduce Moscow’s dominance over European energy markets, and promoted the idea of a stronger transatlantic alliance based on enhanced economic cooperation and security guarantees. At the same time it has advocated for more, not less of Europe—a staggering 70% of Poles continue to believe in the relevance of the European Union project. It’s no accident that the European Council has elected as its new President former Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk.

Yet it’s the new geopolitical context characterised by growing uncertainties over Russia which is contributing to a ‘strategic awakening’ of Poland as an EU leader. With a more aggressive and unpredictable Russia in the east and a fragmenting European Union in the west, dark visions from the country’s not-so-distant tragic history reappear. However, instead of retracting, Poland is looking at ways in which it can contribute to the strengthening of both the EU and NATO as founding pillars of Europe’s prosperity and security. Furthermore, it is reaching out for instruments which will allow it to influence the broader international security order. Examples of Poland’s ambitions which go beyond the Euro-Atlantic cooperation include the country’s recent bid for a UN Security Council non-permanent member for 2018–19 or its endorsement of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). And its leadership momentum, as never before, is being strengthened by three critical factors.

First is Poland’s sense of historic urgency. In just 25 years the country has become an integrated part of the Western institutional system. Thanks to its NATO and EU membership and its successful political and economic transformation, for the first time in centuries, Poland is secure and prosperous. Yet unlike many Western Europeans, Poles are hungry for more. There is a deep understanding that a quarter of a century of prosperity is not enough. And the benefits which have resulted from Poland becoming part of the liberal democratic order are worth fighting for—the fall of this order will hit Poland first.

Next is Poland’s strategic culture. Poland has developed a distinct strategic culture based on the understanding that security is not granted once and for all. Geopolitical concerns, as well as the territorial integrity and sovereignty of the Polish nation, are defining factors of this culture. The country is a reliable NATO member and a strong US ally, evidenced by its readiness to send troops to Kosovo, Iraq and Afghanistan. But Poland also understands that the NATO alliance is only as strong as its member states are. Poland recognises the need to provide for its own defence, rather than relying on others. This is seen in the pursuit of its own missile defense and a ten-year rearmament program (worth US$42 billion), which will guarantee it’ll meet the 2% GDP NATO target for defence spending in the years to follow.

Lastly are Poland’s strategic alliances with the US, Germany and beyond. Poland holds a firm belief that the United States remains the ultimate guarantor of European security just as Germany remains the ultimate guarantor of European prosperity. Its partnerships with both countries remain at the heart of Polish foreign policy. However, disillusionment with the lack of US engagement in Europe, and Germany’s inability to solve the Ukrainian–Russian conflict is giving way to independent strategic thought. Poland is recalibrating its focus towards a more regional approach based on closer security cooperation with the Scandinavian and Baltic states—all of which form the ‘New Security Wave’ thinking in Europe.

As the European geopolitical and security landscape changes, it’s a good time also for Australia to look beyond its traditional interlocutors on the ‘old continent’. The striking closeness of Polish and Australian security culture (which resonates in both countries’ approach to the Ukrainian–Russian conflict and the importance of a military alliance with the US), shared values and economic interests (among others in the energy sector) form promising grounds for cooperation. Both countries, already perceived as possessing significant military capabilities, face a small probability of being attacked directly, but are becoming indispensable security guarantors for its direct neighbors (Poland for the Baltic States; Australia for New Zealand and the Pacific Ocean). Most importantly, dealing up-close with potentially revisionist powers (Russia, China) both Poland and Australia share a deep and strategic interest in assuring that a rules-based international order prevails in the long term. This needs to be done by cooperation but also by the ability to deter. In that sense, a like-minded partner, with a growing geopolitical and military weight, and at the core of the European integration process is surely a partner Australia would value.

Well done (or commiserations) to those diligent souls that have yet to decamp for the summer break. To help soften the blow, here’s the last cyber wrap for the year from the ICPC.

Well done (or commiserations) to those diligent souls that have yet to decamp for the summer break. To help soften the blow, here’s the last cyber wrap for the year from the ICPC.

Last week Bloomberg released an interesting report speculating on the reason behind the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline explosion in 2008. The explosion, in Erzincan, eastern Turkey, had largely been attributed to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK. Bloomberg asserts that the explosion was evidence of one of the first instances of kinetic cyber attack. Apparently, Western intelligence agencies who investigated the attack found that ‘hackers had shut down alarms, cut off communications and super-pressurized the crude oil in the line’. The article links the sabotage to the Russians, who, don’t forget, were the alleged victims of a cyber-linked pipeline bomb in 1982.

The Chinese Communist Party is slowly trying to become ‘hip to the youth’ with its propaganda campaigns. The Economist is reporting that to maintain currency with a tech-savvy and younger audience the Party is supporting and encouraging traditional print media outlets to build an online presence. Interestingly, this type of reporting has ‘repackaged’ traditional forms of propaganda into grabs and headlines that are most likely to attract the eyeballs of a younger crowd. The article even claims that the latest online offering from Shanghai Observer, dubbed ‘The Paper’ is similar in style to the US-based Huffington Post (minus the independent reporting). We wait with anticipation for the propaganda machine to discover lolcats and memes. Read more

The ceasefire struck two weeks ago between Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko and Russian President Vladimir Putin appears to be holding. Might a crisis that has cost 3,000 lives and created up to 250,000 refugees have been avoided?

The ceasefire struck two weeks ago between Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko and Russian President Vladimir Putin appears to be holding. Might a crisis that has cost 3,000 lives and created up to 250,000 refugees have been avoided?

The terms, which seem designed permanently to preclude Ukraine’s entry into the EU and NATO, could be seen as vindicating the realists’ argument that the eastward expansion of Western institutions in Europe lay at the root of the conflict all along. George Kennan’s warnings are well known and Henry Kissinger made his own, with remarkable foresight, during the Kosovo war of 1999.

The same year, journalist Anatol Lieven (now Professor of War Studies at King’s College London) published Ukraine and Russia: A fraternal rivalry, fruit of two years’ interviews with ordinary Ukrainians. It’s a portrait of complex, diverse loyalties—to a distinct Ukrainian nationality defined by language, to a Ukrainian land defined by allegiance to the soil, to a vanished Soviet identity defined by economic function—resulting from centuries of daily mingling and widespread intermarriage. Read more

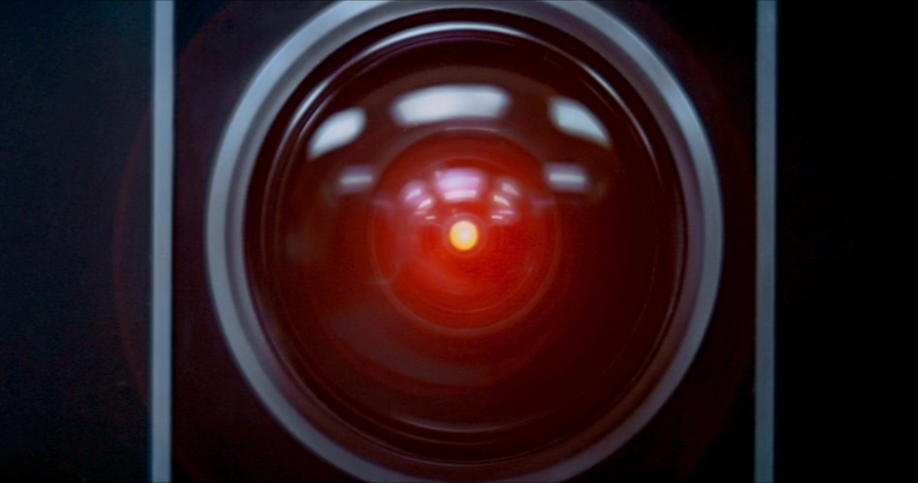

This year’s DEF CON underground hacking conference in Las Vegas has left much to ponder about for cyber professionals the world over. The meet saw John McAfee lambaste Google on privacy, Tesla Motors offer a sacrificial Model S to the hacking hordes, and ‘smart’ thermostats mimicking HAL 9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Dan Geer’s policy proposals were a particular highlight, and have since been labelled the 10 Commandments of modern cybersecurity. A special thanks to the reporters who risked digital life and limb to bring us the highlights from Vegas.

This year’s DEF CON underground hacking conference in Las Vegas has left much to ponder about for cyber professionals the world over. The meet saw John McAfee lambaste Google on privacy, Tesla Motors offer a sacrificial Model S to the hacking hordes, and ‘smart’ thermostats mimicking HAL 9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Dan Geer’s policy proposals were a particular highlight, and have since been labelled the 10 Commandments of modern cybersecurity. A special thanks to the reporters who risked digital life and limb to bring us the highlights from Vegas.

The recent theft of 1.2 billion usernames and passwords by a Russian group shows that you do not need to be in a casino full of hackers to be vulnerable. With the identity of compromised sites still unknown, many have been scrambling to change their login details. While an important part of maintaining cyber hygiene, the effort might be for naught as it turns out your complex passwords aren’t that much safer. Read more

The destruction of Malaysian flight MH17 could hardly have come at a more inopportune moment for Russia, already reeling from Western sanctions and isolation. A growing body of evidence suggests that pro-Russian separatists in Ukraine downed the flight with a Buk-M1 surface-to-air missile launcher, potentially supplied by Russia. Even if the perpetrators mistook MH17 for a Ukranian military aircraft and had no intention of harming civilians, the damage has been done: all 298 passengers and crew on board were killed.

Given how integral the incorporation of Ukraine would be to any program of Russian restoration, it is not surprising that President Vladimir Putin would support pro-Russian separatists there: they played an important role in hiving off the Crimean Peninsula this March, and they are working to dislodge two of Ukraine’s eastern provinces, Donetsk and Luhansk. Unfortunately for Putin, they are evidently willing and able to act outside of his control—a risk he appears to have neglected. Read more

The United States government should never be tempted to embrace a sole purpose declaration in regard to its nuclear weapons policy. As discussed recently by Rod Lyon, (here and here) and Crispin Rovere, such a declaration states that the ‘sole purpose of possessing nuclear weapons is to deter the use of such weapons against one’s own state, and that of one’s allies’.

There’s a pressing need to reassure allies about the credibility of US extended nuclear deterrence security guarantees at a more dangerous time in the world. Those guarantees serve two key purposes. First, they reduce the potential for overwhelming threats to US allies, including Australia (see the 2013 Defence White Paper, para 3.41). Such threats would include nuclear attack, but could also include large-scale conventional or even biological attack. Drawing a degree of strategic equivalence between a nuclear attack and large-scale non-nuclear attacks reinforces deterrence and makes such contingencies less likely to occur.

Second, extended nuclear deterrence security guarantees reduce the risk that states will need to consider acquiring their own independent means of deterrence, including their own nuclear weapons, and potentially generating proliferation cascades that could dramatically destabilise parts of the globe. How would China react to Japanese acquisition of nuclear weapons? How would South Korea? Read more

To gauge the seriousness of the danger on the steppe, one has only to imagine German troops on Ukrainian territory, separated by a narrow front from Russian forces, quite possibly engaging them. If the US were to contemplate involvement, it would have logistical difficulties operating that far from home, not to mention face domestic political pressure to avoid another war (mitigated by a hawkish lobby, as always) and the ever-present nuclear Sword of Damocles. While the reach of American aircraft and drones means they can be used as a decisive force multiplier, any action on the ground to expel Russia from Crimea would have to be undertaken by NATO forces from other states. This would include post-war occupation. They would have to be serious forces. Who? Germany? France? Turkey? These considerations seriously undermine the threat of overt military intervention in Ukraine, especially in the East and Crimea.

This leaves economic sanctions and proxy war as the means of attempting to expel Russian influence from Crimea and, ultimately, take control of Sevastopol. Looking at economic sanctions, the Russian economy is already starting to suffer from the isolation being imposed upon it. Vladimir Putin may calculate that this will ease over time, especially since he can take retaliatory action of his own, including shutting off the gas to western Europe. Suffering of one kind or another will result, though, and Putin will come under domestic pressure. This may well be a calculation of western policy-makers, although the effectiveness of economic sanctions is disputed. There’s also a strain of thought in Russia that sees separation from the west as a good thing. Read more

Kym Bergmann gives an interesting potted history of Crimea up until the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. However, it’s important not to neglect what happened since then. In the case of Ukraine, in exchange for Ukraine giving up nuclear weapons, Russia, the US and the UK agreed to respect Ukrainian borders which included Crimea. The 1994 Memorandum on Security Assurances in connection with Ukraine’s accession to the Treaty on the NPT stipulates that:

1. The Russian Federation, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America reaffirm their commitment to Ukraine, in accordance with the principles of the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, to respect the independence and sovereignty and the existing borders of Ukraine.

And of course there’s the 1997 Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Partnership between Ukraine and the Russian Federation as well which states that:

Article 2. The High Contracting Parties…shall respect each other’s territorial integrity, and confirm the inviolability of the borders existing between them

There are more but lesser treaties that bind Russia, Ukraine and Crimea.

In a rules-based order, treaties are important. Russia has seemingly torn up these treaties it signed earlier. For centuries, diplomacy has relied on an unlegislated social rule between sovereign states: Pacta Sunt Servanda, Promises must be kept. As a sovereign nation, Russia can choose to break the rules, but it shouldn’t be then allowed off scot-free based on its own favourable reading of history.

Kym is right that there’s more to Crimea than meets the eye but to declare that the US President, Secretary of State and the UK PM ‘demonstrate a surprising ignorance of history’ goes a little too far. Instead, they’re supporting a rules-based order. And why shouldn’t they?

Peter Layton is an independent researcher completing a PhD on grand strategy at UNSW. He has been an associate professor at the US National Defense University.

As Sunday’s referendum in Crimea approaches, there seems little doubt that the peninsula’s majority Russian-speaking population will vote for a return to rule by Moscow instead of Kiev. However, it seems unlikely that the result will be accepted by the Ukraine or much of the world community.

It’s extraordinary that such a huge amount of nonsense has been written and spoken about Crimea and then parroted by no lesser figures than the US President, the US Secretary of State and the British Prime Minister—among others, including senior members of our own government. All demonstrate a surprising ignorance of history, which is only likely to harden the position of Russia’s President Putin. Read more