Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

As 2021 dragged to an exhausting end, the international strategic outlook remained bleak.

Authoritarian regimes are threatening conflict in Europe, the Middle East and Asia. The key democracies look distracted, internally riven and unwilling to defend the global order they originally designed.

It wasn’t meant to be this way. The formal dissolution of the Soviet Union on 26 December 1991 was supposed to usher in an era where liberal democracies would flourish. Instead, 2022 may be the year in which democracies operating in a rules-based international order will face their toughest test.

After several decades where Western military forces focused their efforts on largely unsuccessful counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations in the Middle East, we face the alarming prospect of state-on-state conventional conflict in several regional trouble spots.

Russia’s massive build-up of military forces on the borders with Ukraine and Belarus creates the potential for serious conflict during the next few months. A full-scale invasion of Ukraine past the contested eastern provinces would be the most catastrophic but perhaps least likely outcome.

More likely scenarios include Russia overtly moving forces into Ukraine’s Donbas region, which has been controlled by Moscow since the 2014 invasion using local proxy forces and covert Russian military.

Russian President Vladimir Putin then might seek to establish a land bridge between Donbas and Russian-occupied Crimea, widening a front from which Russia could attack deeper into Ukraine.

Putin also could also deploy forces into client-state Belarus, threatening the Ukrainian capital Kyiv from the north, but also putting Russian forces directly on the border with Poland, Lithuania and Latvia.

At this stage, the US and NATO have no appetite for a military response. In early December, US President Joe Biden told Putin in a virtual meeting that, ‘if Russia further invades Ukraine, the United States and our European allies would respond with strong economic measures’.

Beyond that, there were vague promises to provide ‘additional defensive materiel to the Ukrainians’ and fortify eastern NATO allies. Putin has largely been given a green light for military operations and Biden has kept a low profile on the issue for weeks.

This month, the US, NATO and Russia will negotiate on demands from Putin that, if agreed, would severely constrain America’s capacity to defend Europe and would strengthen the position of Russia’s more proximate forces. The US can’t accept Putin’s demands but also won’t offer more than token military support to Ukraine. February may be the month when Russian military operations commence.

What lessons could Chinese leader Xi Jinping take from Putin’s high-risk military posturing? The Beijing Winter Olympics will end in late February. With that charm offensive over, we should expect that Xi will redouble the Chinese Communist Party’s attempts to assert its control over Taiwan and its longer-term goal for strategic dominance in Asia.

China and Russia have become increasingly close since the Russian takeover of Crimea in 2014 and Beijing’s annexation of much of the South China Sea by island building to establish military bases in the same year.

Xi is copying Putin’s international playbook. Both leaders take big international risks—consider Russia’s military intervention in Syria and China’s authoritarian crackdown in Hong Kong—both have championed vast and rapid military build-ups, and both threaten the use of military force to press for Western acquiescence.

Frankly, the strategy is working. Ukraine matters more to Russia than it does to the US and Western Europe. The South China Sea matters more to Beijing than it did to Washington, at least in 2014. Autocratic bluff and brinkmanship can and do produce democratic backdowns.

Imagine a 2022 scenario where Beijing closes the Taiwan Strait to sea traffic and declares the East and South China seas no-fly zones because they are ‘sovereign Chinese territory’. Xi could then build up a huge air and amphibious assault force on the Chinese coast adjacent to Taiwan.

Beijing could activate a propaganda campaign and its own agents in Taiwan, calling for the ‘reunification’ of the rebel province under CCP control and claiming that the US is threatening China’s security by providing military assistance to Taipei.

This would be a Chinese replay of Putin’s tactics over the Ukraine. What would Biden do? If the US response was to threaten economic sanctions but leave military action off the table, Xi could well conclude that ‘reunification’ of Taiwan with China by bluff and coercion is worth trying.

The analogy breaks down because Taiwan is more central to the core of Asian security than Ukraine is to Western Europe. Taiwan under CCP control is an existential threat to the security of Japan and to America’s military dominance of the Pacific. By contrast, Russian control of Belarus and eastern Ukraine adds to NATO’s problems but is not a strategic game-changer.

Here are two more strategic woes likely to unfold this year. North Korea is facing a crisis of domestic economic collapse brought on by international sanctions because of its nuclear-weapon and missile development.

Kim Jong-un’s erratic leadership was marked last year by unexplained disappearances and weight loss that could be linked to serious health issues. A challenge to his leadership would have profound consequences for the stability of the regime.

North Korea manages crises by trying to export them. Expect further missile and nuclear tests designed to extract sanctions softening from the US.

In our nearer region, Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare will continue to lead his country to the brink of disaster by building ties of dependence with Beijing. The proposed Chinese police presence won’t be the last concession China will seek from Sogavare in return for bankrolling his government.

You know Canberra has a real problem on its hands when the political leadership goes quiet. Of course, this is a matter for the Solomons government, but Australia will have no intention of allowing a Chinese proxy to emerge in the Coral Sea. Think back to 1941. This is a game-changer to our security.

Peace on earth? Not in 2022.

As reports pile up about Russia’s military mobilisation on Ukraine’s border and the Kremlin’s diplomatic demands, questions abound. What is going on? What will come next? Will Russia invade?

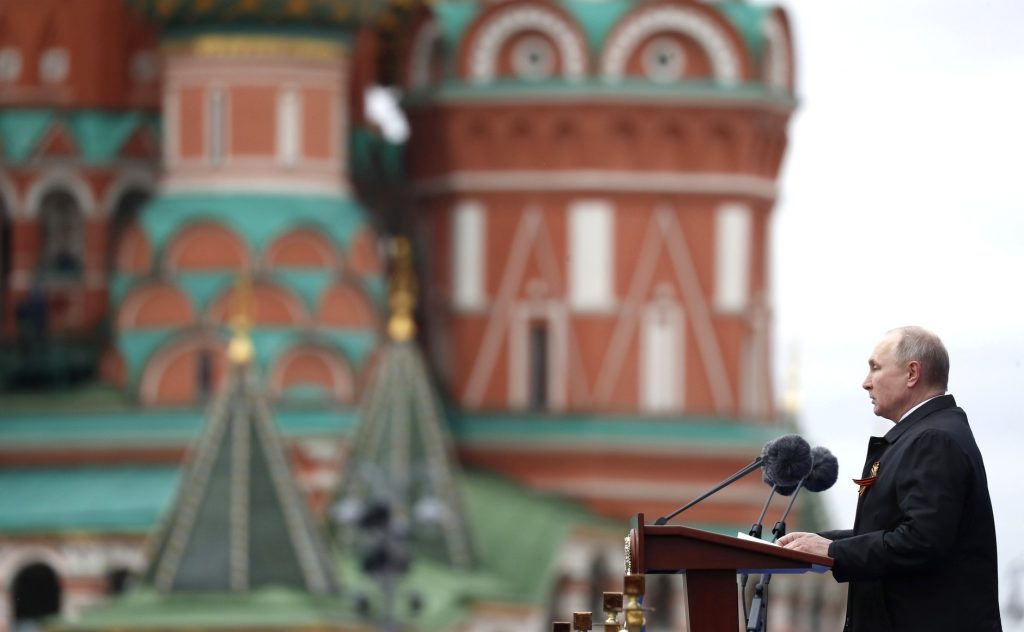

In fact, Russian President Vladimir Putin is following an eight-year-old script.

In the northern autumn of 2013, Putin’s government launched a multifaceted offensive to prevent Ukraine, Moldova and Armenia from signing free-trade agreements with the European Union. That set off a gradually deepening crisis that would profoundly alter Ukraine’s domestic politics, Russia’s position in Europe and the future of NATO. Less than a year later, Russia annexed Crimea and embarked on a barely disguised effort to dismantle the rest of Ukraine. The Kremlin then launched two more incursions into eastern Ukraine to save the separatist statelets that it had managed to set up there.

Since then, 14,000 people have died in this low-level ‘frozen’ conflict. The EU and the US regularly renew their sanctions on Russia, and the United Nations General Assembly regularly condemns Russia’s behaviour and reaffirms the sanctity of state borders. Not only did Putin fail to derail the EU–Ukraine free-trade agreement; he also managed to transform Ukraine from a friendly neighbour into a country that regards Russia as dangerous and hostile. Invading other countries is a historically proven way to make lasting enemies.

Putin now faces the embarrassing prospect of being remembered as the Russian leader who lost Ukraine. He will have set his country back three centuries, to the time before Peter the Great. Even the collapse of the Soviet Union eventually may come to seem less important than Putin’s blunders over the past decade.

Nonetheless, Putin appears to have spent his Covid-19 isolation reading history. This summer, he produced a remarkable essay effectively calling for a greater Slavic empire. Suggesting that power over Ukraine and Belarus ultimately lies within the Kremlin’s walls, he made clear that he intends to recover what his previous miscalculations lost.

The subsequent evolution of Putin’s thinking is unknown. But it is plausible that he spotted weakness in the chaotic US exit from Afghanistan and surmised that America is not keen on yet another foreign entanglement. Whatever Putin’s reasoning, he has since abandoned further dialogue with Ukraine’s leaders, sent German and French mediators packing and concentrated a massive number of tanks in the border region. His goal is to pressure the US to agree to a series of radical demands for restructuring European security; chief among these is that the US rescind its promise, first made in 2008, that Ukraine will someday be invited to join NATO.

Putin’s strategic intent in 2014—to stop the agreement with the EU—ultimately failed. Now, his immediate focus is on regional security issues. Russian officials and state media have been issuing shrill warnings and spinning ominous tales about the US placing missiles in Ukraine to strike Moscow. There is talk of genocide against Ukraine’s Russian-speaking population, and of Ukraine’s imminent entry into NATO.

None of these claims bears the faintest resemblance to the truth. But opinion polls suggest that the propaganda has been effective. Around 39% of Russians believe that war is imminent, and this figure is likely to grow as the Kremlin continues to stoke fear among the population.

In the meantime, Putin has tasked his diplomats with securing US and EU agreement to his maximalist formal demands for a new security order. The manoeuvre is eerily reminiscent of the infamous deal-making done at Yalta in 1945, when the Allied powers discussed how Germany and Europe would be carved up after World War II.

Yet while a further expansion of NATO is not in the cards, the alliance will not accept an arrangement that denies any country the right to shape its own destiny. This issue is bigger than Ukraine. The president of Finland, whose country shares a long border with Russia, has been vocal in pointing out that the option of applying for NATO membership is key to Finnish security. Though he has no intention of launching a membership bid, he can’t allow any outside power to limit his country’s sovereignty. Likewise, countries across Central and Eastern Europe fear that giving in to one Kremlin demand will only invite more.

Is a diplomatic resolution still possible? The path is narrow, and time might be running out. There are proposals to place limits on, and improve the transparency of, conventional forces in Europe. But Russia has rejected many such proposals in the past, and complex arms negotiations would take considerable time. These diplomatic options would not satisfy Putin’s wish to create a ‘Greater Russia’, suggesting that the Kremlin will not rule out military options.

These come in many shapes and sizes. A full-scale Russian invasion would undoubtedly lead to an open-ended conflict that, whatever the original intention, is bound to spill over Ukraine’s borders. If that happened, all options would be on the table for NATO. Severe sanctions and other measures would further squeeze Russia’s already dim economic prospects—even if it secures support from China. More to the point, NATO would finally roar forward to Russia’s border by deepening its presence in its member states that border Russia.

Given this foreseeable outcome, an invasion would be folly in the extreme. But this scenario cannot be ruled out. The Kremlin’s record of profound mistakes in its policy towards Ukraine is long. And while many in Moscow already doubt the rationality of Putin’s aggressive revisionism, their voices carry no weight.

Another more imminent possibility is that the Kremlin will try to provoke Ukraine into doing something that would justify a smaller-scale invasion of the kind we saw in 2014 and 2015. But the escalation risk would be severe, and even a small invasion would expose Russia to severely damaging consequences. Either way, Putin has embarked on a dangerous path.

It is not too late to prevent Putin’s script from becoming a tragedy. Let us hope that he has not been reading Chekhov, who famously advised against introducing a gun in the first act unless it will be used in the second.

Russia’s military build-up along the country’s border with Ukraine has seen tensions rise between the two countries, leading the United States, the European Union and the United Kingdom to warn Moscow against invasion. The Strategist’s Anastasia Kapetas speaks to Russia expert Mark Galeotti from University College London about the likelihood of a conflict, Russia’s diplomacy approaches, President Vladimir Putin’s game plan, and what the objective would be if Russia were to invade Ukraine.

This week, South Korea and Australia signed a billion-dollar weapons contract, making it one of Australia’s largest-ever military deals with an Asian nation. ASPI’s Marcus Hellyer and Michael Shoebridge discuss what the defence contract entails and how this new partnership will influence strategic cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.

In recent months, Russia has positioned a large and capable military force along its border with Ukraine. What we do not know is why Russian President Vladimir Putin has done this (capabilities are always easier to gauge than intentions), or even if he has decided on a course of action. Thus far, Putin has created options, not outcomes.

What comes to mind is July 1990, when another autocrat, Saddam Hussein, positioned sizable military forces along Iraq’s southern border with Kuwait. Then, as now, intentions were murky but the imbalance of forces was obvious. Arab leaders told US President George H.W. Bush not to overreact, convinced it was a ploy to compel Kuwait to take steps to increase the price of oil, which would help Iraq recover and rearm after its long war with Iran.

By early August, though, what to many had looked like political theatre had become all too real. Invasion led to conquest, and it took a massive international coalition led by the US to oust Iraqi forces from Kuwait and restore the country’s sovereignty.

Could a similar dynamic be playing out today on the Russia–Ukraine border?

US President Joe Biden’s administration has reacted to Russia’s troop buildup with a mix of honey and vinegar. The objective is to persuade Russia not to invade by making clear that the costs would outweigh any benefits and that some Russian concerns could be addressed, at least in part, if it backed off. Call it deterrence mixed with diplomacy.

Some have criticised the US response as too weak. But geography and military balance make direct defence of Ukraine all but impossible. Biden was right to take direct US military intervention off the table: not acting on such a threat would only reinforce mounting doubts as to America’s reliability.

But Biden is also right to push back against Russia. The US and the UK, along with Russia itself, provided assurances to Ukraine in 1994 that, in exchange for giving up the nuclear arsenal it had inherited from the Soviet Union, its sovereignty and borders would be respected. This did not constitute a NATO-like security commitment, but it did imply that Ukraine would not be abandoned.

And yet some who oppose direct resistance of Russian aggression against Ukraine support it in the case of possible Chinese aggression against Taiwan. In both instances, geography works against US military options, and in neither is the US bound by an ironclad security commitment. But in the case of Ukraine, NATO allies are not prepared to defend against a Russian attack and are not expecting the US to do so. By contrast, US allies and partners are prepared to resist Chinese aggression and expect that the US would help frustrate any Chinese bid for regional hegemony.

This does not mean Russia should have a free hand versus Ukraine. Whatever order does exist in the world is premised on the principle that no country is permitted to invade another and change borders by force. This more than justifies providing Ukraine with arms to defend itself, as well as threatening to impose severe economic sanctions that would exact a significant cost on Russia’s already fragile, energy-dependent economy.

Biden is also right to offer a diplomatic path for Putin if he decides it would be wiser to walk back from the brink. Several worthy ideas have been suggested: stepped-up US participation in the Minsk diplomatic process initiated in the wake of Russia’s intervention in eastern Ukraine in 2014, a mutual pull-back of Russian and Ukrainian forces from their shared border, and a willingness to discuss with Russia the architecture of European security.

The Biden administration is also right to limit what it offers to Putin. It is one thing not to bring Ukraine into NATO now; it would be quite another to rule it out permanently. The same holds for any assurances that might be extended to Russia about other NATO policies. Diplomacy should never be confused with capitulation.

At the end of the day, what comes next is Putin’s decision to make. He sees Ukraine as an organic part of greater Russia, and may well seek its incorporation to cement his legacy and reverse—at least partly—the collapse of the Soviet Union, which he described in 2005 as ‘a major geopolitical disaster of the century’. One hopes that a policy of raising the costs of invading and offering some face-saving gestures will convince Putin to defuse the crisis he has created.

If, however, deterrence fails and Putin does invade, promised sanctions will have to be introduced. That includes scrapping the Russia-to-Germany Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline and imposing real costs on Russian financial institutions and Putin’s inner circle. It would be a moment, too, to strengthen NATO and provide Ukraine with additional arms, advice and intelligence.

This brings me back to Iraq, but in 2003 and the following years. The US invaded out of a concern that Saddam was hiding weapons of mass destruction and because it saw an opportunity to spread democracy, not just to Iraq but throughout the Arab world. But while the war began with a massive ‘shock and awe’ air campaign and the rapid fall of Baghdad, consolidating military advances proved to be both difficult and costly as urban-based militant groups provided stiff opposition to US-led troops. The American people turned against the war and a foreign policy judged to be overly ambitious and enormously expensive.

A similar fate could await Russia should its troops march on Kyiv and try to control most or all of Ukraine. Here, too, consolidating control in the face of widespread, heavily armed resistance could prove extremely difficult. Large numbers of Russian soldiers would return home in body bags as they did from Afghanistan following the 1979 Soviet intervention. A decade later, Soviet troops were gone from that country, as were the Soviet leaders associated with the invasion. The Soviet Union itself disintegrated. Putin would be wise to reckon with the lessons of this past before deciding on the future.

The vastness of Eurasia is becoming bracketed by belligerence. On the western front, Russia has deployed a growing number of military units to the regions near its border with Ukraine, inviting a flurry of speculation about its motives. And in the east, China’s behaviour vis-à-vis Taiwan has grown increasingly worrisome. A widely reported war-game study by a US think tank concludes that the United States would have ‘few credible options’ were China to launch a sustained attack against the island.

In both cases, the aggressor’s strategic intent is clear. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s government has made a point of calling for Chinese ‘reunification’, regarding that as a fitting conclusion to the Chinese civil war. After World War II, the Chinese Communist Party took over the Chinese mainland but failed to eliminate Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists. They retreated to Taiwan (and some smaller islands), which has remained outside CCP rule ever since.

Sometimes, China’s official declarations about ‘reunification’ have stipulated that it should be achieved peacefully; but on other occasions, China’s leaders have dropped the adverb. And in expanding and equipping its military, China has focused specifically on building its capacity to subdue Taiwan if it ever tries to declare independence.

Most countries, including the US, have long maintained a ‘one China’ policy, withholding formal recognition of Taiwan as an independent state. But in the absence of formal diplomatic ties with the island, many countries have developed relations through other channels such as trade and technology. Taiwan is a world leader in cutting-edge microchip production. It is also a shining democratic success story. If the Chinese society found in Taiwan can be democratic, perhaps the same political vision might someday be extended to the mainland.

At the other end of Eurasia, Ukraine’s situation is radically different from that of Taiwan, not least because Russia has formally recognised its independence. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s occupation and annexation of Crimea in 2014 was declared illegal and condemned by an overwhelming majority in the United Nations General Assembly (where a mere 11 countries voted against the resolution).

Nonetheless, Putin recently published a lengthy and remarkable essay arguing that Russia, Ukraine and Belarus belong together as a matter of history. Ukrainian or Belarusian sovereignty, he now claims, can be achieved only together with Russia, under the ultimate authority of the Kremlin. So far-reaching is Putin’s revisionism that he even criticised Ukraine’s formally independent status under the Soviet constitution (not that this ever meant anything at the time).

Putin’s strategic intent is clear: he regards Ukraine’s independence as increasingly intolerable. Like China with its designs on Taiwan, Russia has been preparing and equipping its military for the specific purpose of invading and conquering Ukraine before any outside force can disrupt the occupation. In addition to seizing Crimea, the Kremlin has already sent regular military forces into Ukraine, as it did in August 2014 and again in February 2015 in the eastern Donbas region. Putin seems both ready and willing to launch another similar incursion, if not a much larger-scale operation.

No one doubts that a Chinese military takeover of Taiwan would radically change East Asia’s security order, just as a Russian military takeover of Ukraine would upend the security order of Europe. But what has not yet been fully appreciated is the possibility of both happening simultaneously in a more or less coordinated fashion. Taken together, these two acts of conquest would fundamentally shift the global balance of power, sounding the death knell for diplomatic and security arrangements that have underpinned global peace for decades.

Such a scenario is not as far-fetched as it sounds. Although China claims to stand for non-interference in other countries’ internal affairs, it is scrupulously silent on the issue of Ukrainian sovereignty. There is no reason to think it wouldn’t back a renewed Russian assault on that country if doing so served its own purposes.

To be sure, it would be a massive mistake for China to invade Taiwan, and for Russia to invade Ukraine. Both countries’ economic development would be set back decisively by the large-scale sanctions that would inevitably follow. The risk of a wider military conflict would be high, and countries like Japan and India would almost certainly embark on a vast military build-up of their own to counter China. Europeans already are moving more decisively toward a policy of strengthening their defence.

As prudent as these developments may be, they offer cold comfort. The drums of war can be heard quite clearly. The task for diplomacy is to ensure that they do not become more than background noise.

During the four decades of the Cold War, the United States had a grand strategy focused on containing the power of the Soviet Union. Yet by the 1990s, following the Soviet Union’s collapse, America had been deprived of that pole star. After the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks, US President George W. Bush’s administration tried to fill the void with a strategy that it called a ‘global war on terror’. But that approach provided nebulous guidance and led to long US-led wars in marginal places like Afghanistan and Iraq. Since 2017, the US has returned to ‘great-power competition’, this time with China.

As a grand US strategy, great-power competition has the advantage of focusing on major threats to America’s security, economy and values. While terrorism is a continuing problem that the US must treat seriously, it poses a lesser threat than rival great powers. Terrorism is like jujitsu, in which a weak adversary turns the power of a larger player against itself. While the 9/11 attacks killed more than 2,600 Americans, the ‘endless wars’ that the US launched in response to them cost even more lives, as well as trillions of dollars. While Barack Obama’s administration tried to pivot to Asia—the fastest growing part of the world economy—the legacy of the global war on terror kept the US mired in the Middle East.

A strategy of great-power competition can help America refocus; but it has two problems. First, it lumps together very different types of states. Russia is a declining power and China a rising one. The US must appreciate the unique nature of the threat that Russia poses. As the world sadly discovered in 1914, on the eve of World War I, a declining power (Austria-Hungary) can sometimes be the most risk-acceptant in a conflict. Today, Russia is in demographic and economic decline but retains enormous resources that it can employ as a spoiler in everything from nuclear-arms control and cyber conflict to the Middle East. The US therefore needs a Russia strategy that doesn’t throw that country into China’s arms.

A second problem is that the concept of great-power rivalry provides an insufficient alert to a new type of threat we face. National security and the global political agenda have changed since 1914 and 1945, but US strategy currently underappreciates new threats from ecological globalisation. Global climate change will cost trillions of dollars and may cause damage on the scale of war; the Covid-19 pandemic has already killed more Americans than all the country’s wars, combined, since 1945.

Yet, the current US strategy results in a Pentagon budget that is more than 100 times that of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and 25 times that of the National Institutes of Health. Former US Treasury secretary Lawrence H. Summers and other economists recently called for the establishment of a US$10 billion annual global health threats fund, which is ‘miniscule compared to the $10 trillion that governments have already incurred in the COVID-19 crisis’.

Meanwhile, US policymakers are debating how to deal with China. Some politicians and analysts call the current situation a ‘new cold war’, but squeezing China into this ideological framework misrepresents the real strategic challenge America faces. The US and the Soviet Union had little bilateral commerce or social contact, whereas America and its allies trade heavily with China and admit several hundred thousand Chinese students to their universities. Chinese President Xi Jinping is no Stalin, and the Chinese system is not Marxist–Leninist but ‘market Leninist’—a form of state capitalism based on a hybrid of public and private firms subservient to an authoritarian party elite.

In addition, China is now the largest trade partner to more countries than the US is. America can decouple security risks like Huawei from its 5G telecommunications network, but trying to curtail all trade with China would be too costly. And even if breaking apart economic interdependence were possible, we can’t decouple the ecological interdependence that obeys the laws of biology and physics, not politics.

Since America can’t tackle climate change or pandemics by itself, it has to realise that some forms of power must be exercised with others. Addressing these global problems will require the US to work with China at the same time that it competes with the Chinese navy to defend freedom of navigation in the South China Sea. If China links the issues and refuses to cooperate, it will hurt itself.

A good great-power competition strategy requires careful net assessment. Underestimation breeds complacency, while overestimation creates fear. Either can lead to miscalculation.

China is the world’s second-largest economy and its GDP (at market exchange rates) may surpass that of the US by the 2030s. But even if it does, China’s per capita income remains less than a quarter that of the US, and the country faces a number of economic, demographic and political problems. Its economic growth rate is slowing, the size of its labour force peaked in 2011, and it has few political allies. If the US, Japan and Europe coordinate their policies, they will still represent the largest part of the global economy and will have the capacity to organise a rules-based international order capable of shaping Chinese behaviour. That alliance is at the heart of a strategy to manage China’s rise.

As former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd argues, the objective for great-power competition with China is not total victory over an existential threat, but rather ‘managed strategic competition’. That will require America and its allies to avoid demonising China. They should instead see the relationship as a ‘cooperative rivalry’ that requires equal attention to both sides of the description at the same time. On those terms, we can cope successfully, but only if we realise that this is not the great-power competition of the 20th century.

In 1965, at the height of the Cold War, the comedy series Get Smart premiered on US television. The popular show featured the bumbling secret agent Maxwell Smart, who represented the American counterespionage agency CONTROL in its fight against its archenemy, an organisation called KAOS—one of whose agents was virtually always Russian.

Today, as a recent RAND study put it, Russia is ‘a well-armed rogue state that seeks to subvert an international order it can no longer hope to dominate’. In other words, having lost control, it is seeking to sow chaos.

US President Joe Biden’s administration is aware of the Russia threat. But, as the recent G7 and NATO communiqués show, it is focused primarily on Russian cyberattacks on American and European targets. As Russia pursues a global grand strategy to expand its influence and undermine the liberal world order, this is not enough.

Russia’s strategy entails, first, intervention in ongoing conflicts to support governments or militant forces hostile towards the West. For example, in the Central African Republic, Russia is providing military and political support to President Faustin-Archange Touadéra. In return, Russian companies are permitted to mine gold and diamonds.

Similarly, in Libya, Russia’s government and its mercenary contractors, such as the Wagner Group, support rebel General Khalifa Haftar, the commander of the Libyan National Army and enemy of the United Nations–recognised Government of National Accord. This has given Russia access to Libya’s oil, transportation and defence sectors. Russia is also using this strategy in West African countries, such as Mali, as the French government seeks to reduce its footprint.

The second pillar of Russia’s grand strategy is arms sales. In Southeast Asia, Russia is selling weapons to Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar and Vietnam. In the Middle East, where the United States is withdrawing, Russia has effectively opened an arms bazaar. In 2017, the United Arab Emirates purchased over US$700 million worth of Russian weapons during the International Defense Exhibition and Conference. Egypt has also increased its purchases of Russian arms over the past decade. After the Biden administration temporarily suspended arms sales to Saudi Arabia at the beginning of this year, Riyadh looked to Moscow.

Russia’s proliferating arms deals partly reflect the fact that it needs the money. After all, its economy has been crippled by Western sanctions and the Covid-19 crisis. But Russia has also signed military cooperation pacts with 39 countries (as of early 2020), which suggests that its motives are not merely commercial.

The third pillar of Russia’s global strategy—which harks back to Soviet tactics during the Cold War—is support for former colonies in pushing back against their ‘imperial masters’ and those masters’ liberal world order. For example, in a meeting with his Sierra Leonean counterpart in May, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov recalled that ‘Russia, and the Soviet Union, made a decisive contribution to supporting the battle against colonialism’ there. Today, Lavrov continued, Russia believes in ‘an African solution to African problems’ and supports developing-country demands for greater representation on the UN Security Council. While that commitment has yet to be backed up by action, the declaration clearly aims to distinguish Russia from the Western countries that resist reform.

Russia is also pushing anti-colonialist narratives in Latin America. According to EUvsDisinfo, the Spanish-language social-media accounts of the Russian state-funded news sources RT and Sputnik have more than 26 million followers. Among the stories the Kremlin is peddling is that the US is blocking delivery of Russia’s Covid-19 vaccine, Sputnik V, to Latin America.

Now, the Russian News Agency (TASS) has announced plans to launch a free Spanish-language newsfeed. It claims it is responding to numerous requests for ‘news reflecting the Russian point of view’ in the local language. ‘Currently,’ TASS General Director Sergei Mikhailov stated, ‘this demand is met by foreign media offering only one side of the story, often hostile to both Russia and the people of the countries themselves.’

The US must do more to push back against Russia. True, today’s Russia is not the superpower it once was, but Russian President Vladimir Putin has proved adept at playing the role of opportunistic international spoiler. The US must respond with a strategy that addresses the full range of Russia’s disruptive tactics.

Soft power is essential here, and the effort to end the Covid-19 pandemic represents a golden opportunity to generate it. The US recognises the critical importance of vaccinating the world. But, beyond rallying wealthy economies to ensure the delivery of vaccines globally, US leaders must mobilise resources for strengthening developing-country health systems in the long term.

The US should also work to win the trust of the populations whose governments are now buying arms from Russia. Biden has already rolled out a strong anti-corruption policy. He should consider also building a global coalition of governments, corporations and civil-society actors to develop and deploy technological tools that enable citizens to participate more directly in holding their governments accountable. For example, civil-society actors are leveraging technology to combat virus misinformation, share accurate data based on national conditions, and empower citizens to engage government institutions. This mobilisation can serve as an example for future efforts to hold governments accountable.

Finally, to counter the growing influence of both Russia and China, the West needs to develop a strategy for building a more inclusive international system. This means, first and foremost, getting fully behind expansion of the UN Security Council, and ensuring that a far wider range of global actors is engaged in shaping the international order. Other forms of international cooperation—such as ‘impact hubs’, which are oriented around multi-stakeholder networks, rather than nation-states—are also worth exploring.

Russia is playing a global game, and the US and Europe are so busy protecting their corners that they are leaving the goals wide open. Only with a global counterstrategy, including a model for a more inclusive international system, do the US and Europe stand a chance of regaining control of the field. They need to get smart.

Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko has once again demonstrated the lengths to which he will go to crack down on his opponents. On 23 May, he deployed a MiG-29 fighter jet to force down a commercial flight, which was traveling from Athens to Vilnius, shortly before it left Belarusian airspace. The purpose was to apprehend Roman Protasevich, the former editor-in-chief of the Belarusian opposition publication and social-media channel Nexta, who was arrested after the plane landed in Minsk.

Why a regime that is already under US and EU sanctions would go so far as to hijack a plane travelling from one EU member state to another is not hard to fathom. Nexta is Lukashenko’s public enemy number one. More than just a news portal with millions of followers across multiple social-media platforms (especially Telegram), Nexta has been the single most important conduit for information in Belarus since the country’s fraudulent presidential election last August.

In addition to reporting on Belarusian security forces’ violent crackdown against peaceful demonstrators, Nexta had provided daily instructions on when, where and how Belarusians should mobilise during last year’s countrywide mass protests against Lukashenko’s bogus election victory. Its Sunday calls for a national march for freedom brought as many as 200,000 people into the streets of Minsk. And all of these demonstrators knew precisely what to do, because they were following the playbook published by Protasevich and his colleague, Nexta founder Stepan Putilo.

Following this unprecedented uprising, Lukashenko’s regime panicked, and for good reason. Nexta was collecting and sharing information and photos from all over Belarus. Every message, photo and call to action that it published went viral, reaching people across the country and around the world.

The key to Nexta’s power was that it based itself outside of Belarus, in Warsaw. The Lukashenko regime could neither turn off its internet connection nor imprison or shoot it, as it was doing with opposition outlets and protesters still in Belarus. Lukashenko was doubtless infuriated by the fact that the protests were being guided not so much by Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, the likely winner of the August election, but by an elusive new-media operator beyond Belarus’s borders.

Since the release in March of a Nexta documentary exposing Lukashenko’s ill-gotten riches (similar to a recent viral film about Russian President Vladimir Putin published by the now-imprisoned opposition leader Alexei Navalny), Lukashenko has been prepared to move heaven and earth to take down his 20-something bêtes noires. In his mind, Nexta is the keystone buttressing all of the various fronts of the resistance.

Because the Ryanair flight Protasevich was on was much closer to Vilnius than to Minsk, the Lukashenko regime’s claim that a bomb threat necessitated an emergency landing in the Belarusian capital is not credible. Once it was on the ground in Minsk, they made a fleeting show of searching passengers and their luggage before quickly apprehending the young dissident and his girlfriend.

The detention of Protasevich’s girlfriend is a classic method of the KGB (as the Belarusian security service is still called), particularly when the intent is to extract confessions. Protasevich is an extremely valuable catch for Lukashenko, because (the dictator assumes) he has the contacts of virtually all of Belarus’s activists. The day after seizing Protasevich, the regime released a video of him admitting to his past participation in the protests.

The same tactic has also been used on Tikhanovskaya, whose husband was already in prison. When she was abducted after the first August protests in Minsk, she was forced to record a speech calling for an end to the uprising, most likely after having seen her husband being threatened with torture. She has since been expelled from the country, and because everyone in Belarus is familiar with these methods, no one blames her for remaining largely on the sidelines.

The hijacking is meant to send a message. To the opposition, Lukashenko wants to say, ‘Your days are numbered. You are traitors, and we kill traitors.’ And to the EU, he has issued a direct challenge: ‘We can make fools of you whenever it suits us, and you will not hurt us, because you are weak.’

Such conclusions are not unwarranted. After all, the Kremlin, whose domestic supporters gloated about the hijacking and Protasevich’s arrest, poisoned Navalny with a nerve agent and paid almost no price for it. The US, UK, EU and others expressed concern and imposed symbolic sanctions, and Russia responded by putting Navalny in a labour camp.

When the Czech Republic revealed last month that Russia had been behind explosions at a weapons depot that killed two Czechs in 2014, the reaction was much the same. In fact, US President Joe Biden’s administration has just waived sanctions against a company building the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline between Russia and Germany. Clearly it’s money, not principles, that matter.

Lukashenko is following Russia’s example. The Kremlin has long gloried in embarrassing foreign security services that try to protect opposition figures, usually by attacking exiled dissidents right under their noses, as with the March 2018 attempted assassination of Sergei Skripal in the English city of Salisbury.

Protasevich had received political asylum in Lithuania. Given that Nexta is based in Poland, it’s worth asking if the Polish authorities did everything they could—or anything at all—to protect and warn him and his colleagues against the dangers they faced. It should have been clear that Protasevich and Putilo were in danger. It’s well known that Russia and Belarus will target those they consider traitors, even when they’re abroad. Now it’s well known how far they will go for that purpose.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s recent annual address on the state of his country was so ostentatiously threatening as to sound reassuring. Not only did he forbid the West from crossing red lines, but he announced that he himself would determine where those lines are. He didn’t specify whether he would inform anyone else—as if it had always been the Creator, not politicians, marking red lines in the past.

He seemingly played chicken with himself—certainly not with the chronically listless West. Few will believe Putin when he suggests that Russia is threatened by the might of the European Union, which can’t even deal with Hungary. The same goes even for the United States. Though President Joe Biden’s administration has just imposed new sanctions on Russia, they appear to be even more symbolic than those levied by Donald Trump—the president elected with Russian help. With the new sanctions, the Russian ruble depreciated for two days but then rose strongly in value.

Not even Russians will find Putin’s threats compelling. That doesn’t mean they will rush to depose him (such moves have always meant trouble, usually resulting in an even worse regime). But there’s little indication that Russians will respond as they did after the annexation of Crimea, when Putin’s popularity shot up.

After all, Russia’s theft of Crimea and eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region hasn’t benefited Russia or its people. After seizing and devastating 7% of Ukraine’s territory, the Kremlin now must maintain those territorial gains by financing mercenaries, building additional infrastructure (like the giant bridge from the Russian mainland to Crimea), and paying benefits to local residents unable to live and work normally.

Moreover, Russia has lost—possibly forever—the goodwill it once enjoyed in Ukrainian society, which historically functioned within the Russian cultural sphere. (The same kind of cultural ‘divorce’ is also now underway in Belarus.) Ukrainians watched Russian TV, listened to Russian music and bought Russian consumer goods; hardly anyone—at least east of Kyiv—was excited about Ukrainian identity. But that has all changed. No Ukrainian politician has done as much as Putin to unite Ukrainians around the idea of Ukrainian nationhood.

Russia’s aggression has also led Ukraine to expand and consolidate its army; pursue deeper cultural, economic and political integration with the West; and enact domestic reforms, albeit sluggishly. Putin has even managed to turn pro-Russian politicians like Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky into heroes of the fight for independence from Russia.

The Russian leader’s next achievement most likely will come in the form of improved polling numbers for Zelensky’s flagging political party, followed by his re-election. With the pro-Russian Opposition Platform—For Life party currently leading in opinion polls, this outcome seemed uncertain until recently. But Putin, that miracle worker, has all but ensured that Russian-aligned forces will lose support.

Elsewhere, Putin’s expanding list of achievements includes ruining political and economic relations with the Czech Republic, which recently expelled 60 Russian diplomats. Before revelations that the Kremlin was behind an explosion at a Czech ammunition depot in 2014 that killed two people, the country’s president, Milos Zeman, was perhaps the most pro-Putin politician in Europe, and Prime Minister Andrej Babis previously opposed extending EU sanctions against Russia. The Czech Republic has now excluded Rosatom, Russia’s state nuclear energy corporation, from its public procurement tenders, too. And, following his latest round of bluster, Putin can forget about distributing the Russian-made Sputnik V Covid-19 vaccine widely in the EU.

Likewise, the Nord Stream 2 pipeline to deliver Russian natural gas to Germany via the Baltic Sea is now hanging by a thread. If the project isn’t completed by the time of Germany’s federal election in September, it could become a mere tourist attraction for divers. The German Greens are currently leading in the polls, and both the German press and German society want the project scrapped. Even if the pipeline were to be completed, as Maxim Samorukov of the Carnegie Moscow Center notes, it’s hard to believe that it would be fully used, given that its original purpose (for Russia) was to exclude Ukraine.

Though we don’t know the exact costs of Russia’s recent deployment of almost 150,000 soldiers, heavy equipment and field hospitals to the Ukrainian border, there’s no doubt that it came at considerable expense to an economy that’s about the same size as that of New York. Russians are acutely aware of these costs. After experiencing 10 years of falling real wages, few are still moved by Putin’s fresh bursts of sabre-rattling.

It didn’t have to be this way. Putin’s Russia could have chosen modernisation rather than murder. Putin’s political lodestar, the Soviet Union, also chose the latter path, and Russia today increasingly resembles nothing so much as the late USSR, ruled at the time by a different KGB man, Yuri Andropov. Russia has achieved exactly as much in Ukraine as the USSR achieved in its 1979–1989 war in Afghanistan.

Now, Russia’s defence minister, Sergei Shoigu, has announced that Russia will start withdrawing its forces from the Ukrainian border region. Apparently, Putin’s speech really was all sound and fury, signifying that he is losing influence both inside and outside the country.

US President Joe Biden is very familiar with both Poland and Ukraine. His decades of service as a United States senator and his eight years as vice president under Barack Obama taught him that the two countries are among America’s most devoted friends and allies. Yet he waited until 2 April—just as Russian troops were once again massing on Ukraine’s eastern border—to call Ukraine’s president, and he still hasn’t spoken to his Polish counterpart.

Biden’s relative silence seems to speak of a policy of ‘benign neglect’, a term coined by Daniel Patrick Moynihan when he was a domestic policy adviser to US President Richard Nixon. But whereas Moynihan wanted Nixon to avoid becoming entangled in America’s racial issues, Biden’s decision to keep Poland and Ukraine at a distance may seem surprising. Although Poland is sliding from liberal democracy into populist dictatorship, Ukraine is desperately trying to consolidate its democracy despite constant Russian meddling and threats.

Moreover, even Poland’s illiberal government still tries to position the country as if it were America’s 51st state, with the US embassy in Warsaw playing a role similar to that of the Soviet embassy before 1989. During Donald Trump’s presidency, a mere phone call or tweet from US Ambassador Georgette Mosbacher was enough to make Poland’s Law and Justice (PiS) party suspend its plans to shut down critical media outlets like the private television network TVN24.

Ukraine, still at war with Russia and heavily reliant on US support (preferably in the form of military equipment or sanctions against Russia), is in a very different position. US support has indeed helped, not least by halting the progress of ‘little green men’ (Russian soldiers without insignia) in the eastern Donbas region after they had claimed some 7% of Ukraine’s national territory back in 2014.

As a result, Russia’s strategy of aggression hasn’t paid off. Its occupation of Crimea and the Donbas—both economically devastated and cut off from the global economy—has come at a massive cost to its budget. More to the point, Russia has squandered centuries of goodwill among Ukrainians, who are now united around their national sovereignty.

Without Ukraine, Russia cannot be considered a global power—Russian President Vladimir Putin’s goal in annexing Crimea and invading the Donbas in 2014. At home, Putin’s approval ratings, which had been flagging, soared above 80% following that invasion. But those gains were only temporary.

If Russia were to conquer Ukraine now, Poland would be next in line. For 250 of the past 300 years, Poland was also part of the Russian Empire. The independence that Poland and Ukraine achieved with America’s victory in the Cold War thus remains a lasting testament to US primacy.

And yet, while Biden’s election victory was met with euphoria in Ukraine, President Volodymyr Zelensky had to wait two months for a call. (The official reaction in Poland to Biden’s election was more muted: after kowtowing to Trump for four years, Polish President Andrzej Duda was among the last foreign leaders to congratulate Biden.)

Biden’s coolness towards the two countries shouldn’t be interpreted as a change in US policy towards the region. After all, he has repeatedly stated—including in a conversation with Putin—that the US will never recognise Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Rather, Biden slow-rolled his call to Zelensky precisely because he knows Ukraine so well.

Biden understands that Ukraine’s anti-corruption reforms are the key to its survival as an independent democratic country. Without these reforms, Ukraine’s oligarchs—some with close Kremlin ties—can simply steal financial and even military aid to the country. Through a show of benign neglect, Biden sought to motivate Zelensky to act against the oligarchs on his own.

So far, the strategy appears to be working. In February, Zelensky approved a decision by Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council to shut down three Russian-language TV channels linked to the oligarch Viktor Medvedchuk. In addition to being one of the leaders of the pro-Russian party Opposition Platform—For Life, Medvedchuk is so close to Putin that he lists him as godfather to one of his daughters. More important, Zelensky also moved against Ihor Kolomoisky, the oligarch who had bankrolled Zelensky’s earlier career as a comedian playing a Ukrainian president on TV.

These moves triggered a series of violent incidents on the informal ‘border’ between Donbas and the rest of Ukraine, killing more than 20 Ukrainian soldiers since the start of the year. With Russian troop movements near the Ukrainian border threatening the security of both Ukraine and Poland, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has claimed that anyone inciting a new war in the Donbas will bring about Ukraine’s destruction.

But it is unlikely that Russia’s ostentatious troop movements are preparation for an actual invasion. Rather, with his popularity nose-diving in the run-up to Duma (legislative) elections this September, Putin is resorting to his old bag of dirty tricks. Indeed, the situation on the ground amounts to a proxy war over Ukraine’s anti-corruption reforms, which both strengthen Ukrainian civil and political society and threaten Russian interests, including by offering an example of cleaner government to Russians themselves. The prospect of a ‘Maidan in Red Square’—a Ukraine-style democratic revolution in Moscow—haunts Putin.

Meanwhile, Duda has yet to hear from Biden. Unlike in Ukraine, America’s benign neglect of Poland has not persuaded that country’s populist rulers to suspend their war on democracy. Instead, the Polish government seems to have decided that maintaining good relations with the US would require too many concessions, threatening PiS’s position at a time when its pandemic policies have dented its popular support (Poland has become a world leader in Covid-19 infections and deaths as a proportion of its population).

Under PiS, Poland’s foreign policy is ultimately a function of domestic policy. As public support for PiS declines, more and more Poles may begin to realise why even their US patron is keeping its distance.