Israel’s ‘neutrality’ towards Russia won’t help Ukraine

With its subdued condemnation of Russia’s assault on Ukraine, Israel has failed to strike a just balance between morality and realpolitik. Given that Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett has refused even to meet with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, the leader of another occupied nation, his effort to serve as a peace broker can hardly be taken seriously. It is an attempt to make up for his government’s own moral shortcomings. While India and America’s friends in the Arab world have also used the pretext of ‘mediation’ to avoid taking sides, they do not share Israel’s pretensions to be ‘a light unto the nations’.

Israel is by far the most favoured US ally in the Middle East, if not the world. Whenever Israel has needed a great power to come to its rescue—such as in the October 1973 war—it has relied not on Russia but on the United States. Its dependence on US support is overwhelming, and its access to the most advanced US weaponry is unequalled, even among America’s NATO allies. Without US backing, Israel wouldn’t have reached the momentous peace agreements that it now has with key Arab powers.

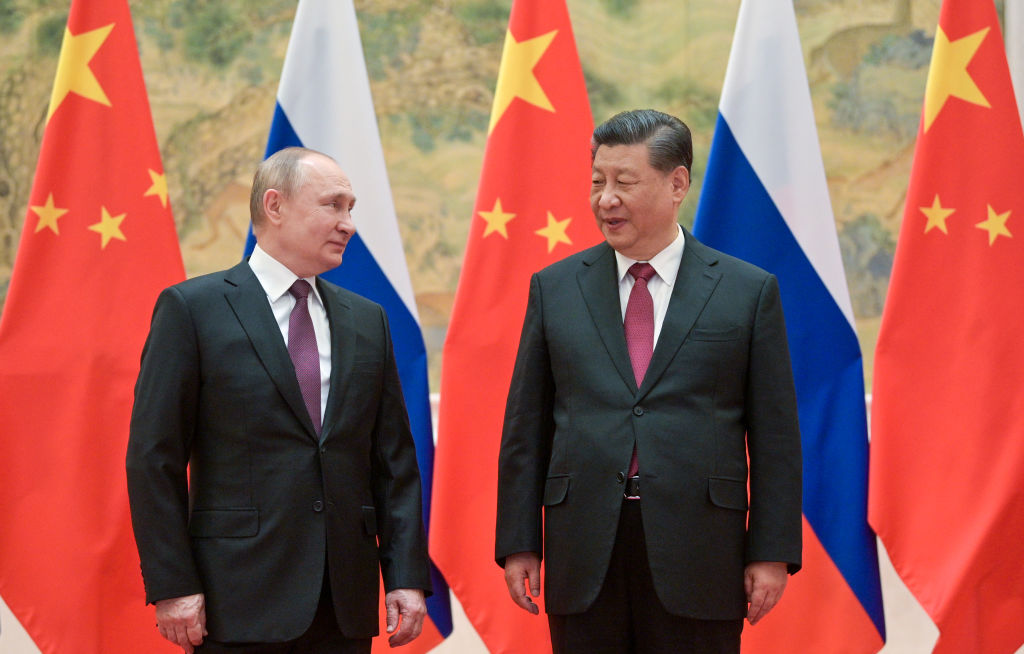

To be sure, Israel voted for the United Nations resolution condemning Russia, and it has sent considerable humanitarian aid to the Ukrainians. But it has refused to criticise Russia publicly or complement the humanitarian assistance with defensive materiel. It even initially denied Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s request to speak before the Knesset lest it inflame Putin’s anger. Apparently, Russia’s green light for Israel to strike Iranian military targets in Syria is more important than standing with the US and Europe to oppose Russian President Vladimir Putin’s reckless, criminal behaviour.

Surely there are other ways to deal with Iran. One would hope so, because the current strategy hasn’t even worked. Israel’s incessant attacks on Iranian facilities in Syria have neither cut off Iran’s Lebanese proxy, Hezbollah, nor compelled Iran to change its behaviour. Now that Iran is on the cusp of securing a nuclear deal that would be weaker than the original Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, a shift from confrontation to diplomacy would seem to be in order. There is no reason to think that doing more of the same will suddenly yield different results.

Moreover, Israel doesn’t owe Putin anything. By allowing the Israeli Air Force to operate freely in Syria, Putin has been able to outsource the task of limiting Iran’s presence in a country that he wants Russia to dominate. Russian–Iranian relations have hardly been on solid ground lately. Most recently, Russia has hindered the signing of the new nuclear deal as retaliation against US sanctions, and conservatives in Iran have criticised the Iranian regime for carrying water for Putin by abstaining from the UN resolution vote.

With Russian attacks on Ukrainian civilians becoming more appalling by the day, the Israeli government’s attempt to straddle the fence has become untenable and indefensible. Ukraine’s heroic Jewish president, Zelensky, has made direct appeals, in Hebrew, to the Jewish people, and Israelis should know more than anyone what it means to be subjected to a strategy of annihilation. Ukraine is a brave democracy resisting the onslaught of an autocracy—precisely the predicament that Israel always claimed to be in during its past wars with Arab countries.

It is worth remembering that Israel refused to consider the nuclear option even during the Yom Kippur War, when its very existence was hanging in the balance. How can the same country remain silent after Russia has explicitly raised the nuclear threat in what is clearly a war of choice? How can this refuge for Holocaust survivors accept Putin’s vile use of the term ‘Nazi’ to describe Zelensky—whose own relatives fought Hitler’s forces and died at their hands? How can a country whose enemies target its civilians not say a word about Russia doing the same in Ukraine?

Israel’s leaders need to pick a side. The choice should be easy. It is between Russia’s tactical acceptance of the Israeli Air Force’s freedom of operation in Syria and Israel’s strategic, long-term moral and political alliance with the US and the West. Israel also needs to recognise the war in Ukraine for what it is: a watershed event that is bound to reshape America’s global priorities. Western containment of Russia will now need to be applied beyond Europe, including in the Middle East. The US has every right to expect that Israel will align with it fully.

If Israel’s government needs any more convincing, it should note that even Turkey’s authoritarian president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has picked a side. Turkey has been an erratic NATO member, purchasing not only Western arms but also advanced S-400 surface-to-air missile systems from Russia. Yet despite the country’s proximity to Russia and dependence on Russian oil and gas, it has unequivocally condemned the invasion and supplied the Ukrainians with arms. Turkish drones have proven to be the most effective weapon the Ukrainians have against Russian tanks.

Israelis tend to see all their wars as ‘existential’ and ethical considerations as luxuries they can’t afford. But there are times when morality and realpolitik align. Israeli leaders should remember that their country’s democracy is a strategic asset. Being an unequivocal member of the democratic front that is resisting Ukraine’s destruction will yield far more dividends than neutrality ever could.