The case for direct military intervention in Ukraine

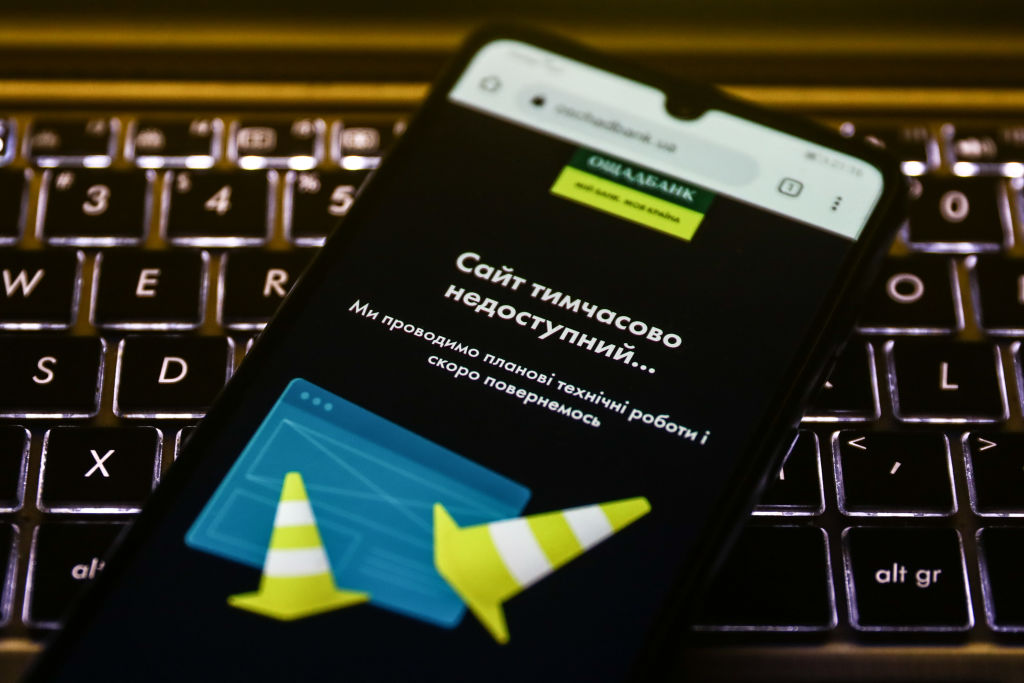

The West is waging a hot economic war against Russia. That Rubicon has been crossed. The West is fighting this war by arming Ukraine and imposing an economic blockade that explicitly aims to eliminate Vladimir Putin’s regime by destroying the Russian economy (and it will be destroyed). As part of this devastating economic offensive, the West has seized around US$400 billion—more than 20% of Russia’s 2021 GDP—from the Russian state by freezing Russian central bank reserves.

War is the continuation of politics by other means, and we are well into other means now.

Yet this war is destined to end in a terrible defeat for the West unless it changes its strategy. The reason is simple: you can’t wage an economic war against a hostile, nuclear-armed opponent if you accept whatever nuclear red lines your opponent chooses to proclaim.

If Ukraine does fall and Russia responds to the economic war with actions backed by nuclear threats, the West is either going to have to either call Russia’s bluff or choose defeat—with all of the terrible consequences that that would entail. So, if the West is willing to call Russia’s nuclear bluff in the unavoidable confrontation to come, then it only makes sense to do it now and intervene militarily to save Ukraine from a second Holodomor.

The economic blockade that the West is imposing upon Russia through sanctions will cripple the Russian economy. Paul Krugman writes that ‘Russia appears to be headed for a Depression-level slump’, and J.P. Morgan predicts a crash in line with that of the 1998 debt crisis. The enormous overall hit to the Russian economy that sanctions will bring about will manifest itself in myriad painful ways. For example, a fascinating Twitter thread suggests that the sanctions regime will largely eliminate Russian civil aviation. The devastating consequences of the West’s economic war on Russia will affect everyone in that country for decades to come.

Yet, as crippling as these sanctions are for the overall Russian economy, they won’t prevent Russia from completing the conquest of Ukraine (though they do have a useful role to play). At that point, Putin will be victorious—on his own terms. He will know that the West watched his forces slaughter Ukrainians because of his threat to go nuclear. He will know that the West has seized US$400 billion of his money and that the sanctions regime was intended to remove him from power. He will know that the sanctions regime will force Russia to rely upon China, in which case his legacy will be to turn Russia into China’s Belarus.

Putin will have to react. And that reaction will have to take the form of a direct confrontation with the West because he will have no other options left. When that confrontation comes, the West will have to either appease Putin by ending the economic war and recognising the Russian conquest of Ukraine or call Putin’s bluff.

The advantage of choosing defeat is that the West will reduce the risk of an immediate confrontation with Russia. However, choosing defeat will also create enormous adverse consequences and will not enable the West to escape from an eventual confrontation with Russia anyway, and on worse terms.

Choosing defeat means that Russia will have successfully waged a brutal war against a country in which the West invested enormous amounts of diplomatic and political capital. The lesson that other hostile regimes will draw is that the West won’t directly interfere in such conquests in the face of a threat to use nuclear weapons. This defeat will therefore encourage both nuclear proliferation and brutal conquests, the combination of which will lead to a far more hostile world for the West and Western ideas.

Choosing defeat will leave Putin triumphant. He will have conquered Ukraine and prevailed over the full diplomatic, political and economic might of the West. Putin has vast ambitions, aiming to do nothing less than ‘relitigate the end of the Cold War, revise the current Euro-Atlantic security system and recreate a sphere of influence in the states of the former Warsaw Pact’. Winning the war in Ukraine while humiliating the West isn’t going to temper them. Putin’s Russia is not going to stop with Ukraine.

Choosing defeat will in fact do little more than set up the next confrontation. In that next confrontation, Russia will once again threaten to go nuclear if the West crosses its proclaimed nuclear red lines.

And what are those red lines? First, Russia cannot lose a war and second, an enemy cannot threaten Russia’s prosperity (I guess that ‘no Russian figure skater shall be subjected to a drug test’ will come later).

These are fabulous red lines if your opponents believe them, because it grants you enormous power over their ability to act. But these red lines are not credible. The US has nuclear weapons precisely to ensure that it isn’t subject to this sort of nuclear coercion. As the 2018 nuclear posture review put it, ‘Potential adversaries must recognize that … any nuclear escalation will fail to achieve their objectives, and will instead result in unacceptable consequences for them.’

Russia is going to attempt to win the war in Ukraine by repeating the tactics it used on the Chechen capital of Grozny in the 1990s. It will attempt to force the Ukrainian population into submission after the war by waging a campaign of murder and terror. The West can prevent this horror by directly intervening in the war with sufficient military force to ensure that Russia’s invasion fails. Russia is planning to get away with this horror anyway by cowing the vastly more powerful West into submission with nuclear threats.

Granting Putin victory in Ukraine will not lead to peace in our time; instead, it will ensure that Putin will confront the West again. At some point, the West is going to call Putin’s nuclear bluff. Let us call that bluff now and save Ukraine.