An Australian maritime strategy: resourcing the RAN

As a country ‘girt by sea’, Australia must enunciate a clear maritime strategy that recognises the scale of its maritime territory and responsibilities, its dependence on trade for its prosperity and the increasing value of activity in the maritime environment.

In a highly interconnected world, we face fundamental vulnerabilities from the realities of our geostrategic situation, and we must be able to defend our national interests. In my ASPI report, An Australian maritime strategy: resourcing the Royal Australian Navy, released today, I argue that the Royal Australian Navy lacks the resources to adequately protect Australia’s vast maritime interests.

This isn’t unique to our time: maritime strategists have long lamented that, despite being uniquely an island, a continent and a nation, Australia struggles to understand the central importance of a maritime strategy to our defence and security. The underappreciation of Australia’s dependence on the maritime domain and its significance for our prosperity and security has consistently produced a RAN that’s overlooked and under-resourced.

Some argue that the AUKUS agreement shows that capability is driving strategy. But to develop a coherent force structure, strategy must drive capability. It’s important that the RAN’s structure and capabilities are driven by a strategy that’s clear and responsive to the circumstances outlined in the 2023 defence strategic review. Many of our partners, including the US, the UK and India, have recognised that and published public maritime strategies, but Australia’s maritime strategy is less clear, and the term itself is conspicuously absent from public strategic documents. A maritime strategy isn’t simply another domain strategy: the defence of our national interests is inherently maritime in nature.

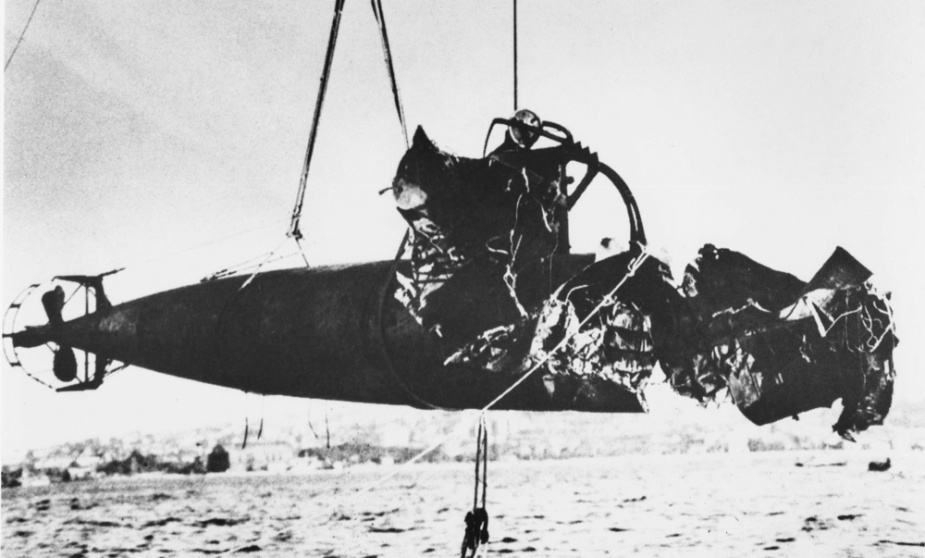

To ensure maritime security, the RAN relies on a backbone of 11–12 major surface combatants. The major surface-combatant fleet consists of eight Anzac-class frigates and three Hobart-class destroyers. All have capabilities in anti-submarine warfare (ASW), anti-air warfare (AAW) and anti-surface warfare (ASuW).

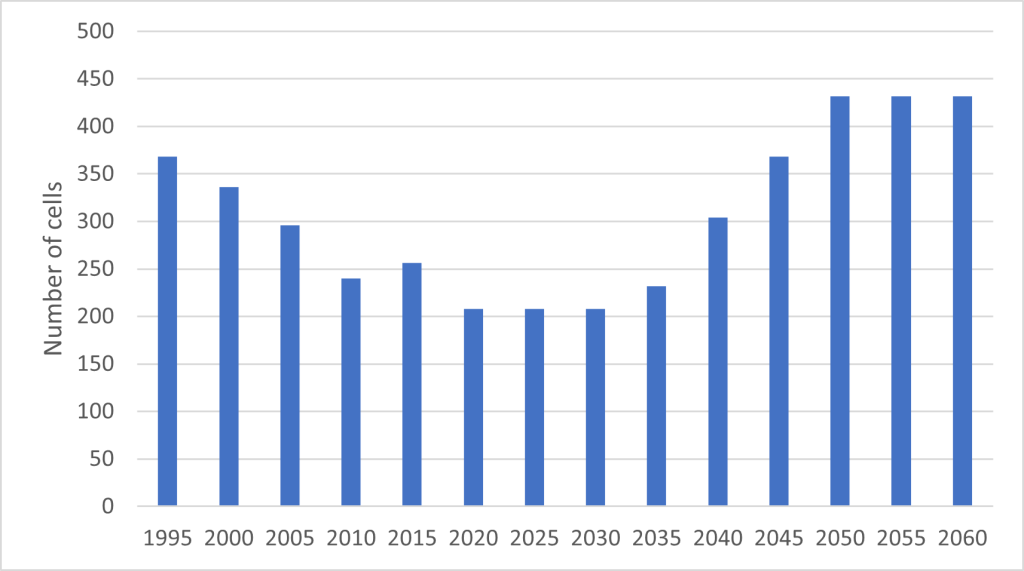

The structure has remained relatively constant for more than 50 years, despite recommendations from multiple reviews that the fleet should have 16–20 ships. While the methodology behind recommendations for an expanded fleet isn’t clear, the context is relevant. Reviews in the 1970s and 1980s were conducted during the Cold War when the possibility of a ‘hot war’ was real. Throughout the 1990s and the 2000s, many policymakers believed that the era of state-on-state conflict was over. However, in the past 20 years, the power balance in the Indo-Pacific region has changed dramatically, and since 2022 Europe has faced the possibility of a major war.

By 2020, China’s military modernisation and its coercive and aggressive behaviour in the region, along with dramatic advances in technology, prompted the Australian government to abandon the assumption that it would have 10 years’ warning of a major conflict to strengthen the Australian Defence Force. But this significant change in strategic thinking, reinforced by the 2023 review, hasn’t brought relevant changes to the RAN’s structure, specifically to the major surface-combatant fleet. A review has been undertaken but its results aren’t yet public.

While Australia’s planned acquisition of eight nuclear-powered submarines under AUKUS to replace our six conventional submarines is important, it doesn’t represent a major structural change or significant expansion of the RAN. The program will significantly increase the capabilities of the RAN’s submarines, but not the overall capability of the fleet designed over 50 years ago.

In my report, I examine whether the bipartisan thesis of a structural change in Australia’s strategic circumstances, articulated in the 2023 review, also requires a structural change in and an expansion of the RAN. I argue that both a larger and balanced surface-combatant fleet and a review of the RAN’s structure are needed. The review should consider bold changes, including reconsideration of a fleet auxiliary, a coastguard or forward basing of assets to support the workforce requirements of an expanded fleet.

The report looks mainly at the structure of the surface-combatant fleet. As the government examines the recently completed surface fleet review, I make eight recommendations for its consideration.

I argue that the status quo of 11–12 major surface combatants is insufficient for Australia. That was the case even when the force was structured around the concept of 10 years’ warning time. The problem has become more acute given the strategic competition and the capability and size of potential adversaries, particularly China, as recognised in the 2023 review. I agree with past reviewers’ recommendations that 16–20 major surface combatants are needed.

The increased number must provide a range of operational effects in a balanced fleet. In this missile era, the planned number of ASW-oriented, multi-purpose Hunter-class frigates should be reduced. I argue that having nine would result in even an expanded fleet being biased towards ASW, with limited ability to field an adequate number of missiles per tonne across the fleet. That would have impact on its ASuW and AAW capabilities.

The scope and length of the report don’t permit consideration of Australia’s naval shipbuilding enterprise or the industry policy of continuous naval shipbuilding, although both must be considered in the expansion of the surface-combatant fleet. I don’t suggest what additional vessels should be acquired, but options include increasing the number of Hobart-class destroyers, modifying the Hunter class, or aligning with the US future frigate (Constellation class) or future destroyer program (DDG(X)). These possibilities all come with their own benefits and unique challenges.

The surface-combatant fleet can’t be viewed independently of broader maritime capabilities, including sealift, mine warfare and civil maritime trade operations, all of which will need to be enveloped in a clear and coherent maritime strategy. Although those capabilities aren’t considered in this report, their interrelated nature highlights why maritime strategy should be driving maritime capability.

Australia’s security and prosperity are intimately linked to the maritime domain, and yet our defence strategy—current and past—doesn’t clearly articulate a maritime strategy. Articulation, production and understanding of Australia’s maritime strategy are essential to deter conflict in the region, and an expanded fleet is required in case deterrence fails.

There’s bipartisan understanding and acceptance that our strategic circumstances will continue to change. That requires structural change of the RAN, not only acquiring a small number of nuclear-powered submarines—with opportunity and substantial risk—but bolstering the surface combatants which are the backbone of any force for achieving sea control and power projection.

This will be challenging and will require sweeping reviews of the wider RAN structure to crew and support that capability, hence the suggested consideration of a coastguard, a naval auxiliary or task groups at different readiness levels. This can’t be delayed. Tinkering around the edges of the ADF and RAN structures will provide neither the necessary deterrent effect nor the capability to defend Australia’s interests should deterrence fail. The dramatically reduced strategic warning time is itself a warning that we must act.