Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Last Friday, the United Nations Security Council voted on a draft resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and calling on it to stop the attack and withdraw its troops. Sponsored jointly by the US and Albania, the resolution received the affirmative vote of 11 of the council’s 15 members. But it was defeated by the solitary negative vote of Russia (by chance the council president for February) as a veto-wielding permanent member. The three countries to abstain were China, India and the United Arab Emirates.

China’s abstention came as a welcome surprise to Western delegates. Ambassador Zhang Jun said that the crisis did not occur overnight, the security of one state cannot come at the expense of another and everyone should refrain from actions that could shut the door to a negotiated settlement. On this occasion, China walked the tightrope between reaffirming its commitment to sovereignty and territorial integrity and supporting Russia’s security interests.

We should not be surprised, however, that, if forced to choose, China will have Russia’s back because their functional alliance, Graham Allison explains, ‘is operationally more significant than most of the formal alliances the United States has today’.

India’s abstention was less welcome and puzzled as well as disappointed many Indophiles. Ukraine’s ambassador to India, Igor Polikha, expressed deep dissatisfaction with India’s vague generalities and boilerplate statements on an immediate ceasefire, dialogue and respect for legitimate interests of all sides, rather than specific and strong condemnation of Russian aggression. India’s special relationship with Russia, he said, made it one of the few countries that could shape Moscow’s policy.

To understand why India abstained, we must look at the complex array of India’s principles and interests that are engaged in the Ukraine crisis. To begin with, this includes the presence of around 18,000 Indian students in Ukraine. Under contemporary conditions of India’s noisy electronic media, no government in New Delhi can afford not to be sensitive to their welfare and, if necessary, safe evacuation.

India has traditionally portrayed itself as a global champion of the inviolability of state sovereignty and territorial integrity on behalf of developing countries against once-colonial powers and weak against strong countries. Russia’s brutal and full-scale invasion violates this foundational Indian foreign-policy value as well as strong material interest, given its own many restive regions, in opposing foreign powers dismembering existing states. Consequently, no matter how sympathetic India might be towards Russia’s security dilemmas, it will not support naked aggression.

That said, Moscow has historically been a major diplomatic ally that has often in the past protected New Delhi’s back in the Security Council. Russia remains India’s most important arms supplier, accounting for almost half of total arms imports (and 23% of total Russian arms exports—its biggest market) in the 2016 to 2020 period. Israel, France and the US are the second, third and fourth biggest sources.

Yet, because India is trying to reduce its dependence on Russia by diversifying arms imports, Russia’s share dropped by half from 70% to 49% from 2011–2015 to 2016–2020. US imports also fell by 46% and those from France and Israel went up by 709% and 82%, respectively, in the same five-year periods. Moreover, in recent years Russia has also become Pakistan’s second biggest arms supplier, albeit still only a fraction of China’s dominant share.

The bigger defence-cum-diplomatic worry for India is the developing Moscow–Beijing axis. China gets 77% of its arms from Russia. Shortly before the Ukraine invasion, China and Russia announced a ‘no-limits partnership’ that includes supporting each other’s policies on Ukraine and Taiwan. For all these reasons, India would be wary of contributing to any further consolidation of the Moscow–Beijing axis, either by the West or by its own actions.

At the same time, India succeeded in gaining US political goodwill and diplomatic backing and a significantly enhanced bilateral defence and security relationship after a protracted and delicate period of courtship in the post–Cold War era when Washington was the world’s most critical capital. That relationship has only grown in importance with China’s continued ascendancy up the relative power ladder, matched by an increasingly assertive posture and belligerent actions towards several neighbours.

India continues to invest heavily in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue with Australia, Japan and the US as the premier Indo-Pacific forum for checking China’s reach and influence in the vast maritime space. India has steadily internalised the new regional and global reality that China is a clear and present security threat as well as India’s most consequential diplomatic adversary across a surprisingly broad front. France is India’s key bilateral interlocutor in Europe, and the EU and UK remain important partners overall.

So, again, India has to thread the diplomatic needle in calibrating its response to a potentially era-defining event like the invasion of Ukraine—the biggest conventional attacks in Europe since 1945.

The invasion also highlights India’s crisscrossing engagement with several loose groupings around which its different international identity and interests coalesce. Yes, it’s a Quad member and a potential partner in the D10 (a proposed grouping comprising 10 large democratic countries) and is able and willing to help shore up a rules-based order. But it is also a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS, alongside Russia and China in both, as well as the G20 and keenly if unrealistically pursuing an elusive permanent seat on the UN Security Council.

New Delhi must accordingly balance all these competing pressures from its extensive engagement in the mandated multilateral and the array of informal groupings that make up the machinery of contemporary global governance. When India was last on the Security Council a decade ago, its votes on the crises in Libya and Syria spanned the gamut from yes to no and abstain. Don’t be surprised if the same happens again, depending on the exact circumstances at the time and the precise language of the resolution up for vote.

Of course, like every country, India will sometimes get it wrong. But rather than unrealistically raise expectations, friendly countries would do well to try to see the world through Indian eyes to appreciate its foreign-policy calculus, instead of counterproductively judging its policies as unprincipled.

Five and a half years on from the international arbitral tribunal’s rejection of China’s expansive South China Sea claims in July 2016, the international maritime order in East Asia clearly is in trouble. China is continuing to consolidate its control over the Paracel Islands and most of the Spratleys group and is increasing its encroachments on the recognised exclusive economic zones of most of the South China Sea’s littoral states with relative impunity. The Philippines and Vietnam in particular have suffered numerous Chinese incursions, and Indonesia’s Natuna Islands and more recently Malaysia’s EEZ have been targeted in China’s bid to control the southern waters of the first island chain.

The region’s maritime order under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is central to the rules-based order that Australia, India, Japan, the US and other likeminded states hold to be central to regional security and prosperity. Yet China’s grey-zone tactics are continuing apace, weakening the authority and relevance of UNCLOS in the absence of a coordinated and unified regional stance supporting its rules and authority both in principle and in practice.

The wider regional implications of China continuing to unilaterally impose its own maritime laws on other states, denying them fishing and other maritime rights, provide compelling reasons for the Quad states, and others, to work harder to ensure that the rights and entitlements of all South China Sea littoral states under UNCLOS are protected. The threats include not only the further erosion of the rules-based order’s authority and legitimacy, perhaps to an irreparable degree, but also a major increase in Beijing’s political and economic leverage over the many Southeast Asian states that continue to depend on the fishing, energy and other sovereign rights China seeks to control.

Allowing Beijing to further expand its already significant presence and influence in the South China Sea would make it much more difficult for Australia, Japan and the US to build regional diplomatic support against China’s actions in the South China Sea and elsewhere, making great-power military conflict in the region more likely.

ASEAN’s role in the disputes remains hamstrung by internal divisions over its responsibility as a regional institution for protecting individual state maritime rights, despite its various statements affirming UNCLOS as the basis for resolving maritime entitlement disputes. Many in ASEAN are fearful of the consequences of being forced to choose between the US and China, of ASEAN becoming marginalised by great-power politics in its own backyard, and of the region becoming more militarised and conflict prone.

The lack of a unified ASEAN stance and response on China’s claims is also explained by fence-sitting among member states that are not directly affected by the South China Sea disputes or whose political and business elites prioritise the benefits of not antagonising Beijing. The fact that rival maritime claimants in ASEAN hold conflicting interpretations of UNCLOS’s provisions has been an additional obstacle to developing a common ASEAN position.

But signs of greater willingness to cooperate on maritime law enforcement and other maritime issues, encouraged by Beijing’s aggressive behaviour, are beginning to appear among the littoral ASEAN states. An agreement between Indonesia and the Philippines on their overlapping EEZs in the Celebes Sea was ratified by both governments in 2014. Vietnam and Malaysia are planning to sign a memorandum of understanding on maritime security cooperation addressing several problem areas, including illegal Vietnamese fishing in Malaysian waters. Vietnam and Indonesia, meanwhile, are continuing negotiations to establish provisional boundaries in overlapping areas of their claimed EEZs in the North Natuna Sea; in December last year the two nations signed a memorandum pledging improved cooperation on maritime security and safety.

These bilateral agreements should be read as both an assertion of the parties’ maritime rights and a clear rejection of China’s illegal ‘nine-dash line’ claims.

Beijing’s deployment of militia vessels for maritime fishing exposes them to suspicion of illegal fishing and thus also to legitimate maritime law enforcement action under UNCLOS. The longstanding problem of Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing in the South China Sea therefore may present an important opportunity for the South China Sea states most at threat from China’s illegal maritime claims—the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia—to collectively develop, with greater capacity-building and regulatory support from the Quad states, a UNCLOS based, non-military means of pushing back against China’s claims and grey-zone tactics.

Doing so will ensure that regional, rather than external, actors take the lead in upholding and affirming maritime rights. It will also provide a broad and unambiguous affirmation of UNCLOS’s authority and relevance and place the onus for any military escalation on China by imposing grey-zone dilemmas on China’s leadership, especially in terms of its own conflict threshold calculations.

Aside from the geostrategic threat that a Chinese takeover of the South China Sea poses, the alternative to cooperative EEZ regulation and better maritime law enforcement is a Chinese-controlled South China Sea. That would extinguish the resource and freedom-of-navigation rights of all other states and make any plans for cooperative or multilateral management (such as through a regional fisheries management organisation) of those resources and rights redundant. The risk of a catastrophic collapse of the region’s biggest fisheries resource due to Chinese mismanagement, intensifying competition and conflict, or both, would significantly increase. Such an outcome would very likely mean more illegal fishing in Southeast Asia’s already depleted waters, and in the EEZs of other states, including Australia and Japan.

By collectively supporting the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam and Indonesia in their efforts to more effectively regulate and police fishing and other maritime activities, the Quad states can indirectly push back on China’s grey-zone encroachments while also helping the coastal states to better manage a longstanding threat to the region’s socioeconomic security and future prosperity.

The AUKUS announcement will reshape the agenda of today’s meeting in Washington of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, a strategic grouping comprising Australia, the United States, Japan and India. While the agenda for this inaugural in-person Quad leaders’ summit would have been agreed weeks in advance, the AUKUS announcement will be a late but significant addition to discussions.

An important first step for Australia and the US will be to reassure their other Quad partners.

Due to the timing, more links are being drawn between AUKUS and the Quad than may have occurred had the two events been further apart. With AUKUS still very fresh, Japan and India will expect additional detail about the deal and reassurance from Australia and the US.

Japan’s Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, whose government has reacted positively to the AUKUS announcement, will appreciate how this deal draws the US and UK deeper into the Indo-Pacific region. While AUKUS could open old wounds in the Australia–Japan relationship, the summit also provides Prime Minister Scott Morrison with an opportunity to smooth things over with his Japanese counterpart. To further reassure Japan, Australia and the US should emphasise the potential AUKUS presents for increased trilateral naval cooperation and interoperability.

With India, the situation is slightly different. The future of India’s trilateral consultations with Australia and France is in jeopardy, in the short term at least, with news today that the French foreign minister has pulled out of a meeting scheduled to be held on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly. However, India appears to believe AUKUS should be considered separate from other minilateral engagements, including the Quad. After the summit and down the track, the US should be prepared for India to seek new military technology deals with it, given that America has decided to share its most secret nuclear technology with Australia.

After reassurance, the summit needs to address what has been a much longer-term challenge for the Quad, its branding.

Despite the Quad committing to provide major public goods in the region, including a billion Covid-19 vaccines, and to cooperate on climate change and critical technology, Quad sceptics and critics remain. Each Quad member has had recent diplomatic, economic or security conflicts with China, and many regional countries are suspicious of the Quad’s underlying motivations. China has criticised the group as an ‘exclusive clique’ that will ‘drive a wedge’ between regional nations. In the absence of a strong public messaging campaign by the Quad, this ‘anti-China’ narrative has gained traction with some countries.

So, how can the Quad improve its image? Quite simply, good branding starts with better public-facing communications.

The Quad has produced a joint statement and a co-written opinion piece, and has announced multiple working groups. But it has no joined-up communications platform to present its achievements. The four nations publish information on the Quad through their national channels, such as the White House and Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade websites.

While it may sound basic, a dedicated Quad web presence would help brand the initiative and provide a single source of official information to help counter inaccuracies. Down the track, a web-based platform could make it easier for the Quad to seize opportunities to partner with industry or civil society groups to help carry out its mandate on issues such as climate change, critical technology, infrastructure and supply chains.

At this stage of its evolution, the Quad’s goals and processes are complex. Step three needs to be consolidation.

The virtual Quad leaders’ summit in March greatly expanded the group’s remit, making pledges on vaccines, climate change and technology. Previous meetings had delivered commitments to cooperate in several other areas: maritime security, cybersecurity, quality infrastructure, supply-chain resilience, counterterrorism, disaster response and countering disinformation. All up, there are now 10 official Quad working groups, on issues broad enough for several subtopics.

Given the Quad is a ‘grouping’ and not an ‘institution’, having 10 areas for cooperation poses significant administrative complexities. The Quad needs to consolidate its existing activities and avoid making any new commitments, including at today’s summit.

One way to achieve this could be condensing its 10 working groups into three overarching pillars—regional public goods, technology and security. Consolidating its efforts in this way would provide structure to Quad cooperation, enable it to better articulate its priorities, and reduce the resourcing required to staff 10 working groups across countries and national agencies.

Having structure is one thing, but where should the Quad focus its immediate attention and resources?

Step four needs to be setting priorities. Delivering on its Covid vaccine commitment to the region is an obvious top priority. The Quad vaccine partnership has been meeting regularly and work is already underway. But what’s next? Because the vaccine commitment is so clearly a priority for the Quad and the broader region, there could be value in identifying what aspects of this pledge made it so compelling.

To begin with, Quad vaccine cooperation is responding to an immediate and overwhelming challenge for the region and stands to deliver a tangible benefit to countries beyond the Quad framework. Quad cooperation also makes sense because each of the four countries brings a distinct but complementary skillset to the table. Regional countries like that this cooperation has had a positive rather than negative character, as military cooperation would have. So, what other areas of Quad cooperation fit this bill?

As my latest paper sets out, the areas that most fit these criteria are critical technology, infrastructure and supply chains. All of these areas represent an immediate challenge for the region. The Quad countries have complementary skills that they are politically committed to, and each has a positive agenda.

This second Quad leaders’ summit presents a significant opportunity, although it also carries risk. The opportunity is to strengthen the Quad brand by creating an online platform to promote the outcomes of the group’s meetings and to consolidate and prioritise its commitments.

The risk is letting this engagement pass without providing more detail on current commitments—how they’re tracking and what’s next—and, worse still, further expanding cooperation, making it more difficult to deliver concrete results in the short term.

An in-person meeting that brings together four of the strongest democracies in the Indo-Pacific is a big deal—let’s hope our leaders use the opportunity for more than symbolism and follow a four-step approach to success.

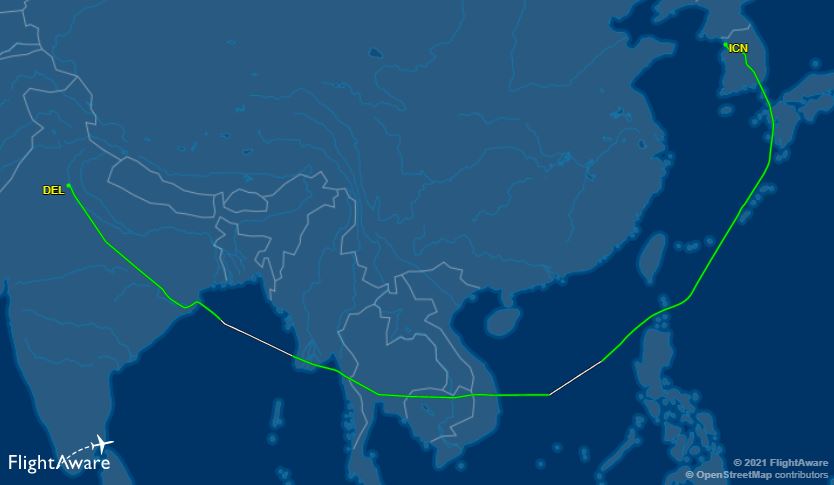

Foreign Minister Marise Payne and Defence Minister Peter Dutton’s flight path on the way to Washington for the annual AUSMIN meeting with their American counterparts provides an insight into Australia’s policy directions and relationships as we look to open up to the world over 2022.

Their trip took them to Jakarta, New Delhi and Seoul, but interestingly flew through Vietnamese, Filipino and other Southeast Asian airspace, avoiding Chinese airspace by taking a long way around that can only have been deliberate.

A side leg to Tokyo and a fuel stop in Singapore were all that were missing to signal core trusted partnerships for Australia in the region in the twin eras of a prolonged Covid-19 pandemic and aggressive Chinese power.

As they arrive in Washington, what should we want out of the peak Australia–US ministerial forum? There’s a shopping list of activities that will demonstrate an urgent, shared and positive agenda for this 70-year-young alliance. An enhanced US military presence in Australia, expanded Australian naval facilities for US and other Quad and regional partner cooperation, a quantum tech partnership, joint missile production and space are all on the menu.

But, beyond any particular item on that list, what we—and the wider world—need out of the Australia–US relationship is ambition and initiative, and not just from America.

Investing intellect and resources in our future shared wellbeing, prosperity and security with trusted partners is the path Australia must take into 2022. This is the core outcome we want from AUSMIN and the Quad leaders’ meeting that Prime Minister Scott Morrison is having next week with US President Joe Biden, Indian PM Narendra Modi and Japanese PM Yoshihide Suga.

One purpose of both AUSMIN and the Quad meeting is a thread that connects Canberra, New Delhi, Jakarta, Seoul and Tokyo, as well as European partners who are increasingly recognising the Indo-Pacific as a place that combines their economic and security interests. That’s to chip away at the empty notion that the issue of our times is making—or avoiding—a choice between the US and China.

The uncomfortable realisation is growing that there is no choice, and that the real challenge from China is not one for the US alone but should concern every open society and indeed any other sovereign state that doesn’t wish to have its choices dictated and constrained by the regime governing China.

But the broader combinations of European and Indo-Pacific states need momentum, which can come from the actions of tighter groupings and partnerships. Our US ally is essential here, both for its scale and capacity but also because it too is seized of the need to create momentum through action and investment. And Australia, as an activist nation, is probably best placed to work with the US at speed and to set directions through our own policy thinking and creativity.

Like the American public, Biden is clearly tired of the US needing to be the source of every agenda and is likely to welcome Australia as a provider of analysis, ideas and proposals (as occurred with 5G) around which the alliance and his emerging foreign, security and economic policies can build.

There’s good news here, if our political leadership understands the opportunity we have and the path we can take to achieve it.

The arc of Australian security and economic policy is to make China matter less and to deepen our engagement with partners we can trust, in a world where shocks and disruption from the natural world and from Chinese state power are likely to continue and accelerate. It’s not about changing Chinese government fundamentals, but about recognising them and what they mean.

In direct security terms, Payne and Dutton can use our growing defence budget to invest in enhanced naval facilities in Australia’s north and west and use them as key enablers for ourselves and for US, Indian, Japanese and other partners’ maritime operations through the Indian Ocean and up into Southeast Asia and the wider Pacific.

This investment will grow Quad cooperation faster than potential adversaries expect and so help deter conflict in our region. It’s likely to unlock co-investment from the US and, in coming years, from other security partners seeking to make a more visible contribution to Indo-Pacific security. France and the UK come to mind.

And beyond physical facilities for our own military and cooperation with others, Payne and Dutton might propose cooperation on the national security elements of quantum technologies and on co-production of advanced missiles in Australia to supply both the Australian Defence Force and US forces in the region.

Both of these areas will require Australian investment along with deep government-to-government agreement if we are to achieve any tangible outcomes for our security in anything like the near term. But both are essential for Australia to be able to operate and succeed in future conflict, and therefore to deter such conflict. For example, making concrete progress beyond technology demonstrators in the area of uncrewed undersea systems and seeing space as a truly transformational area for the alliance and security would be fantastic.

That type of ambitious agenda at AUSMIN will set the scene for a wider program at the Quad leaders’ meeting next week. Far from stealing the thunder of that meeting, it will allow Morrison to use the momentum from the more focused national security forum to Australian advantage at the Quad. And there, he must build on the directions that the first ever (though virtual) Quad leaders’ meeting established in March.

Then, the Quad leaders announced joint work to speed up the production and distribution of Covid-19 vaccines to partners in the Indo-Pacific, notably Southeast Asian and South Pacific populations, in the knowledge that no one part of the globe will truly be able to deal with Covid until the wider world has access to population-level vaccination.

The effort bogged down as India experienced a surge of infections, but now the leaders can anticipate growing vaccine production and availability out of both the US and India over the coming 12 months.

Now is the time to plan for these vaccines to be distributed rapidly and widely in small Pacific states and in the populous nations of Southeast Asia. We know from Australia’s domestic vaccine rollout that time spent planning distribution with our South Pacific and Southeast Asian partners will be time well spent.

Australia must spend the money required to establish an onshore production capacity for mRNA vaccines to complement our AstraZeneca production. As Bill Gates has observed, Covid-19 won’t be the last disease to cause havoc in our world, and new variants are likely to emerge. This fact alone makes a national vaccine production capacity, with scale to help our near region, both a smart and an essential investment.

For the doubters and economic rationalists, it’s worth remembering that South Pacific economies like Fiji and Vanuatu depend on Australian and New Zealand tourist spending. If we want to avoid these island states requiring large structural economic assistance programs from international lenders and donors—like Australia—then helping them reopen to us as we reopen to the world makes simple financial sense (as well as being the right thing to do).

A vaccine production capability would be fed by Australia’s hugely capable medical and biotechnology research outfits, and so be much more than an assembly line for others’ vaccines.

The last area of Australia–US and Australia–Quad cooperation that Morrison might use his time in America to supercharge builds out of this sector.

Biotechnology is what brought the world the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines in record time. Applied to agriculture, for example, it’s also what will create climate-change-resistant crops to feed Australia, our region and the rest of the world as the impacts of climate change grow.

Australia has an enormous opportunity to build on our history of agricultural research partnerships with ASEAN economies. We can use the power of the Quad to accelerate agritech research to address the food-security pressures we know are coming our region’s way, and do so ahead of time to drive the wellbeing, prosperity and security of our near region and our own people.

Ambition and initiative backed by investment. Commodities that are rare but of increasing value as we look to 2022.

With the spotlight recently on Russia’s relations with the US and Europe, following the meeting between presidents Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin and the G7 and NATO summits, less attention has been paid to the complex challenges facing Russia in Asia.

Hard on the heels of the inaugural Quad summit between the leaders of Japan, Australia, India and the US in mid-March, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov visited China, South Korea, India and Pakistan to underscore Russia’s continuing relevance.

Lavrov’s talks in New Delhi aimed to bolster Russia–India ties. He underlined Moscow’s concerns about the Quad, repeating Russia’s opposition to the creation of security blocs in the Asian region. In December, Lavrov had sharply criticised the Quad as part of a US-led ‘persistent, aggressive and devious’ policy intended to ensnare India in its ‘anti-China games’ and designed to undermine the close partnership between Moscow and New Delhi. Russia also claims the Quad is divisive and undercuts ASEAN centrality.

Why is Russia so unhappy about the Quad? Because it sees it as a potential gamechanger, disrupting Russia’s position and strategy in Asia.

Russia’s so-called pivot to Asia over the past decade reflects political and economic drivers, both given impetus since 2014 by Moscow’s post-Crimea estrangement from Europe and America.

First and foremost among Russia’s priorities in Asia is China. The close and growing strategic partnership between Moscow and Beijing reflects political affinities, economic complementarities and foreign policy convergences.

But it remains a pragmatic, transactional relationship, and Moscow is conscious that growing asymmetries make it the junior partner.

Concerned to retain autonomy, Russia has sought to balance its close ties with China by expanding relations with other Asian states, especially India but also Japan and ASEAN states. Little headway has been made with Japan, with the intractable Kuril Islands dispute impeding progress. Efforts to intensify economic links, especially energy and arms sales, with partners like Vietnam and Indonesia have made more headway, albeit off a low base.

Russia engages in Asian regional institutions, notably ASEAN, APEC and the East Asia Summit, to underscore its regional credentials, complementing its stepped-up bilateral activity.

Underpinning its Asian swivel, Russia has promoted its Greater Eurasian Partnership idea as a platform for engagement with the wider Asian region, based on institutions such as the Eurasian Economic Union and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation—in which Russia plays a leading role. Moscow has advocated greater cooperation between the EEU and ASEAN, and supports observer status for the EEU at APEC. Russia has sought to leverage its geographical location to promote its relevance to greater connectivity between Asia and Europe.

Moscow fears, though, that the emerging Indo-Pacific strategic concept, especially closer security cooperation within the Quad, jeopardises its position in Asia.

Conceptually, the Indo-Pacific construct is a maritime-based cooperative framework, as opposed to the continental Eurasian-centred vision for regional integration promoted by Russia. Whereas the Eurasian cooperative model would confer a leading role on Russia, it’s not clear to Moscow how it might fit into the Indo-Pacific framework.

In practical terms, Moscow worries that the Quad, perceived as a US-orchestrated security coalition against China, will complicate Russia’s efforts to strike some balance in its relationships with China and other key Asian regional countries, especially India.

If the Quad gains momentum, drawing in Asia–Pacific players such as South Korea and ASEAN, Russia fears that it will become more isolated and be compelled into greater dependence on China than it would like.

India is a particular concern. Moscow knows that New Delhi’s growing anxieties about Beijing, including military rivalry, underpin India’s involvement in the Quad. Moscow worries this will encourage New Delhi’s tilt towards closer cooperation with the US, weakening Russia’s own ‘special and privileged partnership’ with India.

India has tried to mollify Russia, talking up the Indo-Pacific as a principles-based, inclusive and unifying construct and encouraging Moscow to view it positively as an opportunity—but to no avail.

Moscow remains suspicious of where India is heading. And, realistically, while Russia is an important partner for India, especially in energy and defence, the overall relationship remains thin, compared to India’s growing and diverse connections with the US and others.

In this context, Lavrov’s subsequent visit to Pakistan—his first in a decade—was a clear warning to New Delhi. During talks in Islamabad, Lavrov discussed expanding Russian security assistance to the Pakistan military—a move that would alarm India.

Alive to potential marginalisation, Moscow will strive to bolster its relevance and importance as a credible major actor in the wider Asian region. Expect further intense Russian bilateral and regional diplomacy over coming months, as well as efforts to diversify ties with other Asian partners, such as Bangladesh, Pakistan and Myanmar. Moscow will try to lift its modest military presence and influence in the Indian Ocean, building on the recent naval basing agreement with Sudan and military exercises with India, Iran and Pakistan.

But with the Quad’s importance likely to grow, giving visible form to the Indo-Pacific strategic construct, the challenges facing Russia’s Asian diplomacy will not diminish.

‘Global strategic focus has shifted to the Indo-Pacific. How the region handles the next few years will determine if it becomes the cradle of crises or solutions.’

— Cleo Paskal, Indo-Pacific strategies, perceptions and partnerships, Chatham House, March 2021

Editors often conjure a good yarn on a big issue by dispatching journalists out to different places to ask the same question.

The contrasts and rhymes of diverse pubs, parishes and peoples do the alchemy, pulling the story together. Travel the miles and spend the time. Repeating a good question all over the place can turn up gold. It works as well for an academic research paper as a TV documentary.

Chatham House has just done this with a question for our times: the meaning and purposes of the Indo-Pacific. You’ll not be surprised that China looms large in the answer.

Chatham House talked to 200 experts in seven countries: the US, the UK, France, India, Tonga, Japan and China, recounted in Indo-Pacific strategies, perceptions and partnerships, by Cleo Paskal. The story she tells is how six nations regard the seventh, China.

The six aren’t as one on what the ‘Indo-Pacific’ is (the French policy community, characteristically, wants the term more clearly defined, while their Indian counterparts see benefits in ambiguity), but the six know what the construct is about: ‘[A]ll agree, to some degree or another, that the primary driver of increasing interest in the Indo-Pacific is China’s growing economic and strategic expansion.’

Looking out to 2024, the survey found three major themes:

The shock of the pandemic and the cascading impacts of China have united polities. Domestic divisions have diminished, Paskal writes, with more willingness to push back:

The pandemic has had such a severe economic effect in all six countries that the cost of some sort of ’decoupling’ from China can appear relatively minor in comparison. It seems less of an issue to rock the economic boat if that boat is already sinking.

The power of China and the expanding construct of the Indo-Pacific demand a response from even small capitals like Nuku‘alofa. Tonga switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China in 1998, has substantial loans from Beijing, and joined the Belt and Road Initiative.

Paskal describes Tonga as ‘a clear example of increased strategic interest in Oceania, with the UK reopening its diplomatic mission there, Japan stepping up military engagement, and the US offering the country a partnership with the Nevada National Guard’.

For Nuku‘alofa, the surge in interest provides ‘more options’, which is the classic South Pacific stance. International interest means more potential donors; the skill is to play with all suitors, never settling for one. The more the merrier—Tonga wants to add India to the mix—is the established formula to achieve a balance between ‘partnerships and independence’.

On the other side of the world, France is ‘one of the least divided and most certain countries’ because its economic, political and defence outlooks are ‘closely aligned’. The aim is to shape its own Indo-Pacific reality, ‘unabashedly built around pragmatic French interests’. Paris may not be able to engage as widely in the Indo-Pacific, but it’s ‘likely to engage more deeply’. President Emmanuel Macron’s vision of a ‘Paris–Delhi–Canberra axis’ reaches into the Quad while not being in the Quad.

UK foreign policy is ‘undergoing epochal change’ and a ‘fundamental reassessment’. London’s view of China has toughened over Hong Kong and Huawei. The UK’s integrated review promises to deepen ‘engagement in the Indo-Pacific, establishing a greater and more persistent presence than any other European country’. Weigh that ambition against this comment on interviews in London: ‘When foreign policy participants were asked if the UK was a great power, there was often an awkward pause, followed by a variation on “not really”.’

Japan has the opposite problem: it’s a big player with the polite mien of a middle power. Paskal reckons a loss of trust in China as a long-term investment could substantially shift Tokyo’s position. But she ends with the familiar problem of whether Japan will step up as a big power or merely decline and recline:

It is possible that Japan will increasingly line up with its allies and partners in a stronger, rounded stance against Beijing. However, it is also possible that domestic economic and political lobbies will successfully weaken any effective pushback on China. Much will depend on the direction taken by Washington, and how that affects Tokyo.

India’s tone ‘has shifted substantially’, with much less hesitation in embracing the Quad. Paskal notes calls for an India–US ‘alliance’—though not the sort of alliance ‘recognized by lawyers’ but the sort ‘recognized by generals’. The June 2020 border conflict in the Himalayas saw popular opinion turn strongly against China:

A series of decisive actions took place, including banning Chinese apps on security grounds, restrictions on foreign direct investment, restrictions on visas for certain Chinese people, and a shift to a more forceful military strategy.

For India, as with everyone else, hedging behaviour is turning prickly, because the hedging space is contracting. ‘Countries are being forced to pick a side,’ Paskal writes, predicting ‘a new era of alliances and partnerships’.

The conclusion is a call for an Indo-Pacific charter, expressing a consensus on acceptable behaviour, rules and norms:

An Indo-Pacific Charter is one way to reduce domestic division, uncertainty and hedging by making clear internally and internationally what nations that sign stand for, in the same way as the Atlantic Charter did in 1941 … [T]he goal would be to create partnerships strong enough, and with enough levers (including economic), to dissuade nations that want to dominate unilaterally. That could mean economic boycotts or supply-chain redirecting, rather than naval blockades.

To celebrate International Women’s Day 2021, the ASPI podcast crew are excited to share this brilliant all-female line-up with defence, foreign policy and national security expertise.

Danielle Cave, deputy director of ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre, is joined by Tanvi Madan, director of the India Project and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, to discuss India and the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue and the prospects for increased collaboration between the Quad countries.

ASPI’s Lisa Sharland speaks with Jenna Allen, research assistant for Deane-Peter Baker at UNSW’s Australian Defence Force Academy. Jenna shares some insights into her journey in building a career in defence and national security and outlines some of the work of UNSW’s ‘Women in Future Operations’ group.

The Strategist’s Anastasia Kapetas and ASPI research intern Khwezi Nkwanyana highlight the achievements of four pioneering women in foreign correspondence: Ida B. Wells, Martha Gellhorn, Oriana Fallaci and Claire Rewcastle Brown. In tracing their influence and groundbreaking work, the discussion captures some of the history of trailblazing women journalists.

The effectiveness with which Russia and China have been able to exploit situations to make territorial gains has exposed a chronic vulnerability for collective defence regimes. Collective defence risks becoming unfit for an era of strategic competition in the grey zone.

The Quad implicitly acknowledges this and has developed as a collaborative defence arrangement that can respond to the sorts of threats China poses.

For the Quad to succeed in this way, Australia, India, Japan and the US will need to work together using force—or tactics that sit above or slightly below the threshold of armed conflict—to block Chinese attempts to seize territory. They’ll also need a coherent strategy to counter China’s other activities below the threshold of armed conflict.

This will require a broad understanding of defence using different elements of national power to counter a range of coercive threats. Each member will need to understand which levers should be pulled at what times in a coherent strategy that thwarts Beijing’s ability to achieve its political objectives at each stage of competition or conflict.

The more coercive the power China mobilises, the fewer levers of national power the Quad members would need to pull. In a hypothetical example in the first part of this series, I described how Quad members might develop an effective military response to a Chinese attempt to seize Pratas Island from Taiwan. In that case, the four members of the Quad would be pulling down heavily on the military levers of national power—albeit at different stages of the conflict and in different theatres.

Responding to the most coercive of China’s threats is the easiest part of the Quad’s job. It gets harder if China mobilises less coercive power when threatening the Quad’s interests in the Indo-Pacific. This is where the distinction between collective defence and collaborative defence becomes key.

Over time, China has reclaimed land and transformed islands into military facilities that have increased its ability to project power across the Western Pacific. This has raised the costs for the US to defend its treaty allies, which undermines its presence in Asia.

For Japan and Australia, China’s South China Sea facilities pose a threat to the freedom of navigation each relies on for trade.

In India, the stakes may not be as high, but any erosion of international norms in the South China Sea would set an unwelcome precedent as the Chinese military increases its presence in the Indian Ocean. So far, the differing stakes for each country in the Quad have made a collective response impossible.

However, an effective response to China’s grey-zone coercion need not be ‘collective’. In 2017, Ely Ratner, Biden’s top China adviser at the Pentagon, argued in Foreign Affairs that the US should ‘abandon its neutrality and help countries in the region defend their claims’.

Ratner suggested that the US help treaty allies such as the Philippines with joint land-reclamation projects, increased arms sales and improved basing access. Other Quad members would also need to draw upon their own bilateral partnerships to help claimant states build resilience to Beijing’s grey-zone operations. The Quad would be a subtle means of helping Southeast Asian claimants defend their sovereignty against China’s creeping expansionism.

Ratner’s proposal shows collaborative defence in action with the aid of the Indo-Pacific’s established great power. While Washington is laying the groundwork to compete with China in the grey zone, Australia could strengthen its maritime capacity-building initiatives and joint naval exercises with Malaysia and Indonesia in archipelagic Southeast Asia.

India and Japan could each increase the frequency of their bilateral naval exercises with Vietnam. The Quad could agree to conduct Exercise Malabar in the South China Sea, while members of the ‘blue dot network’ could jointly finance critical infrastructure projects in littoral states. An effective strategy would require each Quad member to use a mix of diplomacy, aid, military exchanges, arms sales, joint exercises and new basing infrastructure.

None of these initiatives will achieve results immediately, but nor did China’s island-building campaign. Over time, each initiative will shift the burden of escalation back to China. With each Quad member working independently and collaboratively to embolden claimant states to defend their maritime rights, Beijing will incur new risks when rotating new fighters on Fiery Cross Reef or contemplating further incursions into the Natuna Islands.

Collaboration will allow each Quad member to find out how best to draw on its bilateral partnerships to embolden claimant states to defend their interests. The Quad will be invisible, but omnipresent in Southeast Asia. That’s precisely the threat that Beijing doesn’t want to deal with.

To succeed as a collaborative defence arrangement, the Quad needs to be guided by three principles. Its members need to work independently on their bilateral relationships to improve claimant states’ ability to defend their interests; they must exercise together whenever strategic circumstances require it; and they need to share notes on regional strategy, knowing it will be much harder for China to secure further territorial gains if it’s on the back foot.

Adhering to these principles will enable the Quad to realise its potential as a collaborative defence arrangement that can counter China’s grey-zone operations.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo is scheduled to visit Jakarta tomorrow to meet with his Indonesian counterpart, Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi. With an itinerary including stops in India, Sri Lanka and the Maldives, it’s clear that the goal of the visit is to persuade Indonesia to align itself more closely to the US-led Quadrilateral Security Dialogue in confronting security threats from China.

The US has been pulling out all stops to try to persuade Indonesia; witness its willingness to overlook Indonesian Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto’s history of human rights controversies in granting him a visa for a recent visit after more than 20 years in the cold.

From the Indonesian perspective, however, there are several problems with this goal.

First, Indonesia has steadfastly maintained a position of neutrality, fearing it might be dragged into conflicts that it doesn’t want. An independent and active foreign policy, which eschews formal military alliances, is a fundamental part of Indonesia’s strategic culture. Thus, Indonesia flatly rejected a recent US request to host spy planes on the grounds that it would be against Indonesia’s historic position of neutrality, which saw it become one of the founding members of the Non-Aligned Movement. Any deviation from these principles would be bound to cause domestic uproar, something President Joko Widodo can ill afford as he battles to contain the Covid-19 pandemic and resuscitate the economy.

While the Quad bills itself as a dialogue, it is slowly evolving into a mechanism for military cooperation against the perceived threat from China. Even as elements in Indonesian society and the military are willing to consider support for the Quad in the future, at this point the consensus is one of wait and see, and the outcome will depend significantly on whether China increases its aggressiveness in the South China Sea.

Second, Indonesia has growing economic and investment links with China that could be jeopardised by closer alignment with the US. China’s trade boycotts against Australia in response to Canberra’s firm stance on suspected foreign interference and its call for an investigation into the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic have been duly noted in Jakarta. While it maintains a huge trade deficit with China, Indonesia can’t afford to pick a fight with Beijing because it needs Chinese investment, especially in infrastructure and heavy industry, to jump-start the economy.

Finally, and most importantly, there’s a question mark over whether the US can be relied upon to continue its favourable approach towards Indonesia. Indonesian military officers are generally apprehensive about the idea of a US president from the Democratic Party, believing that a Democratic administration would put more emphasis on human rights, and be more prepared to intervene in Indonesia’s domestic affairs, in contrast to a business-like Republican Party.

They do not forget that it was the Clinton administration that pressured Indonesia to leave East Timor and imposed a military embargo that wrecked Indonesia’s armament program for years. It was the Republican Bush administration that finally lifted the embargo. To be sure, President Barrack Obama, a Democrat, is seen positively in Indonesia due to his brief childhood connection to the country and his efforts to forge a stronger bilateral relationship as part of his Asia ‘pivot’. But Indonesia’s military didn’t miss the fact that the Arab Spring happened on Obama’s watch, in which they saw the hidden hand of the US meddling in the domestic affairs of Arab states on the pretext of concern for human rights.

In fact, Indonesia’s defence white paper specifically notes that the ‘Arab Spring, political and security upheaval in Egypt, [and] civil wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and Syria’ are examples of major powers waging proxy wars. Not surprisingly, several high-ranking military officers I spoke to said they are hoping President Donald Trump will beat Joe Biden in the 3 November presidential election because that would mean the US would continue to act favourably towards the Indonesian military. A Biden victory might jeopardise that, putting the spotlight back on the question of human rights, especially human rights in the provinces of Papua and West Papua, which remains a touchy issue for Indonesia.

All this will force Indonesia to maintain its hedging game, welcoming the Trump administration’s outreach, but remaining wary of any abrupt change in US policy that might be detrimental to Indonesia’s interest.

It seems very likely that Biden, should he defeat Trump, would want to continue his predecessor’s outreach to Indonesia, considering that there is very strong bipartisan support in the US on the need to take a hard line towards China. Indonesia, of course, will deal with whomever the American people chose to elect. But should Biden wish to court Indonesia’s support, he would need to deal with some historic legacies that have left many here doubtful about the durability of US friendship.

The Quad is more notable for the questions it provokes than the answers it offers.

The informal dialogue between the US, Japan, Australia and India is a discussion groping towards a grouping.

ASPI’s paper Quad 2.0: New perspectives for the revived concept notes that the second coming of the Quad ‘has become one of the most debated and contested ideas in current geopolitics’.

Much heat and light is directed at a small process—reborn in 2017—meeting informally at officials’ level, offering no formal statements or agreed view of the world.

The lack of answers emphasises the quality and quantity of questions about the Quad, a small beast grappling with big issues.

The man who sank Quad 1.0 when he was Australia’s prime minister, Kevin Rudd, illustrates that in his discussion of the big questions that caused his new government to pull out of the infant quadrilateral in 2008. A decade on, they’re still great questions.

Rudd published the second volume of his memoirs late last year, after the rebirth of Quad 2.0, and he devotes nearly two pages to his reasons for pulling Australia out of Quad 1.0.

The former prime minister gets stroppy about what he calls the ‘demonstrably false’ claim that he sank Quad 1.0 to appease China. When The Kevin gets stroppy, the details of the argument are piled on as the exasperated tone builds. Normally, exasperated Kevin builds his case with a central set of facts surrounded by statements of argument and conclusion.

In the case of the Quad, though, he fires off a barrage of questions about the historical baggage Japan and India have with China and the possibility of future zig-zags in the way New Delhi or Tokyo deals with Beijing. Plus, he muses on how a four-way alliance would impact on Australia’s bilateral alliance with the US.

Japan: Looking back at the 2008 debate, Rudd poses this question on Japan: ‘[W]hy would Australia want to consign the future of its bilateral relationship with China to the future health of the China–Japan relationship, where there were centuries of mutual toxicity? For Australia to embroil itself in an emerging military alliance with Japan against China, which is what the quad in reality was, in our judgment was incompatible with our national interest.’

India: While not as toxic as Sino-Japanese relations, Rudd writes, India and China had fought a violent border war in 1962 and still had thousands of square kilometres of disputed border regions that periodically erupted into violent clashes. ‘So did Australia want to anchor our future relationship with Beijing with new “allies” which had deep historical disputes still to resolve with China?’

Allying with Japan and India: ‘If the quad became formalised, where would that place Australia if we then had to take sides in Delhi’s or Tokyo’s multiple unresolved disputes with Beijing? A further danger we faced was, if Australia proceeded with the quad, what would happen if domestic political circumstances later changed in either Japan or India? Governments could change through elections. Even the policies of existing governments could change. Australia would run the risk of being left high and dry as a result of future policy departures in Tokyo or Delhi. Indeed, that remains a danger through to this day.’

The US alliance: Australia is already bound by what Rudd calls the ‘far-reaching’ provisions of the ANZUS Treaty to support the US in the event of an armed attack on US forces in the Pacific. ‘Strengthening a bilateral alliance is one thing’, he writes. ‘Embracing a de facto quadrilateral alliance potentially embroiling Australia in military conflict arising from ancient disputes between Delhi, Tokyo and Beijing is quite something else.’

For Rudd, the absence of a quad didn’t preclude strengthening bilateral security cooperation with India or Japan ‘outside the framework of any more binding set of quadrilateral treaty or sub-treaty arrangements’.

The former prime minister concludes with an attack on ‘sloppy analyses’ that he sank Quad 1.0 to ‘please Beijing’. Rudd writes that his government was ‘perfectly prepared to adopt a hardline approach towards Beijing whenever our national interests and values demanded it’, pointing to his approach to human rights and the China-sceptical language of Australia’s 2009 defence white paper.

As for Quad 2.0, that gets one sentence: ‘The extent to which political and strategic circumstances may have changed a decade later is another matter entirely.’

Another matter entirely! Such brevity from The Kevin tells you something about the perplexities and prospects of the reborn quadrilateral.

If times have changed, does that mean the answers to Rudd’s big questions have changed?

Perhaps we’ve moved beyond the loud ‘No!’ that Rudd gave to what he envisioned as a ‘de facto quadrilateral alliance’.

Now, the same prospect gets a faintly mumbled response that sounds something like: ‘Hmm. Well, perhaps. Maybe. Too early to say, really.’

It’s a long way from informal talks among officials to even a de facto form of alliance. Yet, as The Kevin says, political and strategic thinking has changed.

The questions Rudd poses about Quad 1.0 are equally fascinating today. Let’s summarise them into two monster posers for Quad 2.0 to ponder: What is China going to do? What must the US, Japan, Australia and India do together?