A new chance for the Middle East

The word ‘opportunity’ rarely appears in the same sentence as the Middle East, and for good reason, but there is a case for suggesting we are approaching an exception. An opportunity—if not for lasting peace, then at least for an end to the ongoing conflicts and the prevention of new ones—is in fact knocking. The question is whether political leaders will open the door.

Israel has decimated the military capability of both Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon. But continuing military action on its part is running up against the law of diminishing returns, as fewer high-value targets are left.

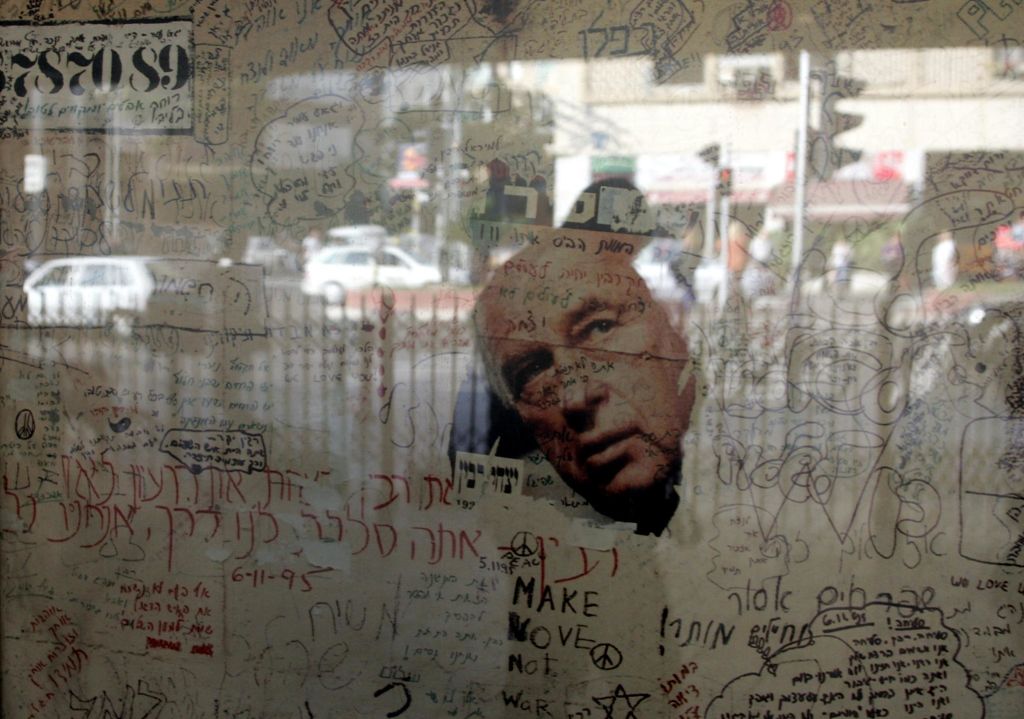

Moreover, continued military efforts threaten the country’s regional and global standing. The International Criminal Court’s decision to issue arrest warrants for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former defense minister Yoav Gallant is the latest indication of the political isolation and economic sanctions that could become Israel’s fate unless it changes course.

The case for a ceasefire on both fronts is strong. The recent agreement between Israel and Hezbollah requires Hezbollah (which is so weakened that it dropped its insistence that a ceasefire in southern Lebanon be linked to one in Gaza) to move its heavy weaponry north of the Litani River, away from the border with Israel. Lebanese troops will patrol southern Lebanon, and the Israel Defense Forces will withdraw from the area and agree not to maintain a presence. Israel has obtained assurances that under certain conditions it would still be able to take military action against Hezbollah to frustrate the group’s attempts to reconstitute itself along the border or if it were preparing to attack.

This accord, if it holds, permits some 60,000 Israelis to return to their homes after more than a year of displacement. In addition, the ceasefire will allow Israel’s exhausted and overextended military to recover and focus on other challenges, including Iran, which is inching ever closer to developing a nuclear-weapons capability that would pose an existential threat to Israel. And the ceasefire should spare Lebanon and its people further devastation.

Yes, the ceasefire will also allow Hezbollah a degree of time and space to regroup, which is why some in Israel oppose it. That said, open-ended military operations will accomplish little, as Hezbollah can be weakened but not eliminated. Israel’s past failed occupation of southern Lebanon demonstrates as much. Israel’s goal, which this agreement puts within reach, should be to restore deterrence.

Gaza poses a more difficult challenge. It is not clear that Hamas would agree to a ceasefire, although it is much weakened militarily and might have difficulty resisting one if Israel agrees to terms that are widely deemed reasonable.

But will Israel agree? It should, because a ceasefire would allow the return of the more than one hundred remaining hostages in Gaza, half of whom Israeli intelligence services believe are still alive. Moreover, as with Lebanon, it is far from clear that Israel stands to gain from continuing military operations in Gaza. Hamas is certainly unable to launch another attack like the one it carried out on 7 October 2023. But Israel’s refusal to start a diplomatic process that would give Palestinians a chance to secure elements of their nationalist aspirations has made it possible for Hamas—with its insistence on endless struggle—to remain relevant.

The big question, then, is whether Israel would agree to a political process that holds out the possibility (however distant, conditional, and vague in terms of territorial reach) of creating a Palestinian state. In the near term, such a process would pave the way for the entry into Gaza of a regional stabilisation force and the establishment of diplomatic relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia. Over time, a Palestinian state properly constituted would enable Israel to remain both Jewish and democratic as well as prosperous and secure.

Some in Israel much prefer a future that allows for Israeli settlement of parts of Gaza and annexation of large swaths of the West Bank. And if they do not get their way, they have vocally threatened to bring down Netanyahu’s government. That is a risk Netanyahu has been loath to take, given that, once out of office, he faces pending legal action and official investigations into Israel’s failure to anticipate and respond to Hamas’s 7 October attack.

Donald Trump, whose return to the Oval Office on 20 January 2025 is already looming over these dynamics, could prove to be the critical variable. While the Israeli right sees his return as an opportunity to achieve maximalist aims, even calling 2025 the year of Israeli sovereignty in the West Bank and an opportunity to begin reducing Gaza’s Palestinian population through ‘voluntary emigration’, Trump has expressed a desire to calm the region.

Trump is in a position to achieve this goal. Owing to events in Lebanon, Netanyahu may be sufficiently strong to stare down his right-wing coalition partners, form a new government without them, or even get a fresh mandate from the voters. And even if not, Trump, whom the Israeli right see as a friend, could lean on Netanyahu and his government in a way that President Joe Biden never could. It would be more difficult for Netanyahu to resist Trump’s pressure, and much easier for Trump to apply and sustain such pressure, given his support among American evangelicals and certain American Jewish communities.

Richard Nixon comes to mind. Nixon, it is said, was able to reach out to Mao’s China because he alone didn’t have to worry about Nixon.

Much the same now applies to Trump. He could build on the ceasefire in Lebanon and press for one in Gaza, launching what would be a promising diplomatic process. Pulling this off would constitute quite a coup for the 47th president. The opportunity is there for the taking.