Recruiting Pacific islanders into the ADF requires a change in policy, not law

In a recent article in The Australian, I argued that the next step in our Pacific step-up should be recruiting Pacific islanders into the ADF. The measure fits with the ‘Pacific family’ idea, as it’s really all about defending the family.

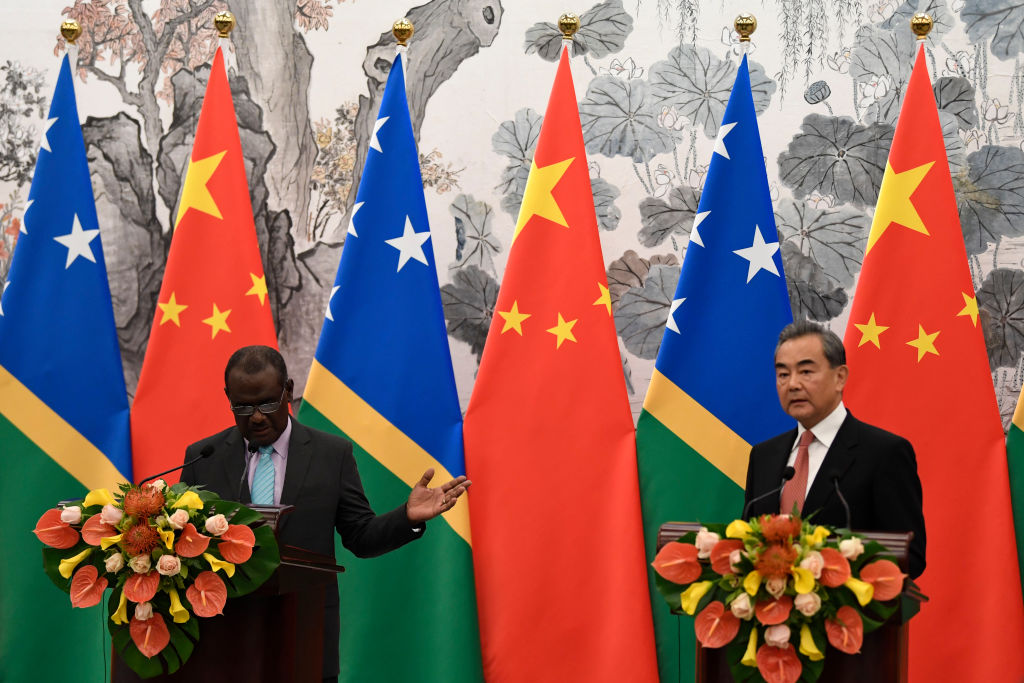

Pacific recruitment sits comfortably with the goal set out in our latest foreign policy white paper of security and economic integration with Australia over time and at a pace and scale that’s welcomed by Pacific island countries. Military service is a unique offer we can make that countries such as China can’t and won’t.

It would be an active addition to Australia’s own security by increasing our defence capability. The defence organisation is having trouble keeping personnel numbers stable, let alone meeting the relatively modest 8% increase set by the 2016 defence white paper.

Here I’d like to respond to two objections I received to my idea. The first was that the Australian Defence Force cannot consider enlisting or appointing people who aren’t Australian citizens.

But if we look at the Defence Department’s website, it makes it clear that a person who isn’t an Australian citizen, under current legislation, can be a member of the ADF.

It states:

Options for non-citizens

In exceptional circumstances, if a position cannot be filled by an Australian citizen the citizenship requirement may be waived and applications may be accepted from:

– Permanent residents who can prove they have applied for citizenship

– Permanent residents who are prepared to apply for citizenship after they have completed 90 days of relevant Defence (effective) service [emphasis added]

– Overseas applicants with relevant military experience …

It’s true that successive Australian governments have maintained the view that all members of the ADF are Australian citizens. But as Defence’s own website shows, this is a matter of policy, not law. There’s no requirement in the Defence Act 1903 that mandates this, as opposed to a policy decision to require citizenship.

The most straightforward way of showing that you can be a member of the ADF without citizenship is to go to section 23 of the Australian Citizenship Act 2007, which sets out the amount of time a person must be a permanent resident in order to apply for citizenship (the other provisions for becoming a citizen are listed in section 21).

It makes clear that a person who has completed ‘relevant defence service’ (at least 90 days), or a member of the family unit of such a person, can apply for citizenship.

There is also a 1940s case of a Greek national being conscripted into the ADF when he wasn’t a citizen (at that time, not a British subject). Back then, all that was required for conscription was living in Australia for six months. Speros Polites challenged that as unconstitutional. But the High Court said that it’s possible for the Commonwealth to do that (even if it’s a bad policy idea since it may mean that Australians overseas might have the same thing done to them).

In short, the law shows that you can be a permanent resident without citizenship serving in the ADF. My suggestion on Pacific recruitment for the ADF could be played out in that context. Indeed, in my article I suggested that ADF enlistment should enable Pacific islanders who might be recruited to become Australian citizens.

The other objection I received was that we shouldn’t need to recruit from the Pacific islands when there are already Pacific islanders living in Australia who could provide a source of recruitment. I am not overlooking these people: Pacific islanders who are here and are not yet citizens could be eligible for recruitment if there were a change of policy.

But what I am advocating is that Pacific islanders who aren’t residents be able to apply to join up and come to Australia on the basis of enlisting.

It was also raised with me that the New Zealand Defence Force gets its Pacific personnel from New Zealand’s own population. But many Pacific islanders in New Zealand have a special status under law that doesn’t apply to Australia’s relations with islanders from former colonies.

In summary, my proposal should not be rejected because it’s a change in policy; after all, the whole point is that this would be a new initiative.