Australia should look back to go forward in the Pacific

Recent events in the Pacific have left Australian officials and analysts searching for policy options that don’t simply double down on Australia’s existing approach to the region. Australia’s comparative foreign policy advantage in the region must be something more than the depth of our pockets.

ASPI’s Michael Shoebridge has proposed one response: moving beyond the Pacific Australia Labour Mobility (PALM) scheme. He suggests that that might look something like the Australia – New Zealand Closer Economic Relations agreement, coupled with the visa-free status enjoyed by (most) kiwis. Shoebridge’s suggestion is gaining traction, including outside of the defence and foreign policy commentariat.

The renewed focus on trade and labour mobility arrangements with our near neighbours, and indeed the closeness with which great-power manoeuvring is now being watched in the Pacific, bring to mind earlier phases of Australian policy in the region. There was a time when Australian statehood was seriously discussed for the Territory of Papua and New Guinea. There’s also a long, often disturbing history of Pacific islands labour in Australia.

These oft-forgotten periods are worth revisiting for more than history’s sake. Numerous Australian governments have already canvassed questions about open borders and labour mobility, the intricacies of political association and more.

Those discussions usefully point to the tricky politics involved in immigration and foreign policy reform that still resonate. It’s as important as ever to be cognisant of our colonial past in the Pacific, which continues to shape our contemporary regional relationships.

Papua New Guinea gained self-government in 1973 and full independence in 1975. Prior to those steps, the country was administered by Australia as a territory, comprising the Territory of Papua (transferred from Britain in 1906) and the United Nations trust territory of New Guinea (originally seized from Germany in 1914). People born in Papua prior to 1975 were Australian citizens, though they didn’t enjoy the full travel and residency rights of citizenship and most lost them upon independence. Those born in New Guinea were not citizens at all. In practice, few Papuan Australians travelled to the mainland.

Well into the 1960s there remained vast uncertainty about the territory’s path towards decolonisation. In 1965–66 there was serious, if short-lived, discussion about incorporating the territory as an Australian state.

In the same period, Ian Downs, a former senior colonial official and member of the territory’s house of assembly, argued: ‘We haven’t got a choice; we have got to find a way to bring the Territory into close association with Australia.’ Even setting aside statehood, one senior official pressed the question: ‘What will be the migration laws into PNG and Australia?’ Paul Barnes, the minister responsible, noted that ‘self-government does not preclude association’. The discussion was serious enough within bureaucratic circles that a senior official in the Attorney-General’s Department canvassed the constitutional feasibility of a transition from territory to state.

The official post-war history of the territory (written, as it happens, by Downs) records that a 1967 Roy Morgan poll found that a third of Australians would accept New Guinea as an Australian state, with another third wanting it to remain under Australian control. Officials pointed out that the Australian people were unlikely to accept the implications of full statehood for the territory, and that independence was the only internationally acceptable position—and the one ultimately chosen by the people of PNG.

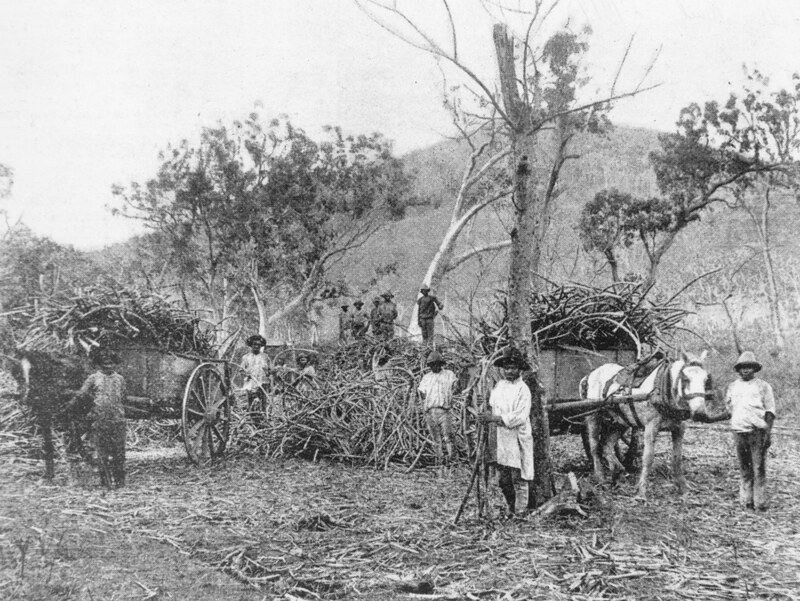

The history of South Sea Islander labour in the Australian sugar and cotton industries is also instructive. Between 1863 and 1904, an estimated 55,000 to 62,500 islanders were brought to Queensland and New South Wales. Many were kidnapped in the process known as ‘blackbirding’ and worked under brutal conditions, though from the 1880s many came without such overt coercion. While some returned home after completing their contracts, many were deported and others died in Australia. Those that remained in Australia in the first half of the 20th century faced a framework of discriminatory labour laws designed to ‘protect’ white workers.

So, what do we know that might guide us now?

First, the politics of immigration with our near neighbours has always been fraught. Domestic labour market politics is complex enough, and any immigration policy reform quickly gets implicated in that potential minefield. Recent immigration settings have targeted highly skilled labour; arrangements with our Pacific neighbours target different demographics. Race is also latent in any discussion on this subject, and Pacific islander Australians report significant levels of discrimination.

Second, if the government does decide to pursue reforms, the policy work will need to be top-notch and integrated across government from the start. For instance, would Pacific citizens (and potentially their families) under new and far more generous visa or residency arrangements have access to Australian social services and medical care, and on what terms? On what basis might they access training and education through our school, TAFE and university systems? Investment here would be important to ensure that isolated changes to the immigration architecture don’t produce an exploited underclass, as infamous migrant worker schemes have done elsewhere. Done right, that training and education could also ultimately improve the dividend paid to Pacific nations.

This applies to how Australia administers immigration, too. The government’s immigration function now sits within the Department of Home Affairs, positioning that arguably privileges the security dimension of immigration decisions. To maximise the benefit of a radically changed relationship between Australia and Pacific countries, the benefits of the contribution of these temporary, long-term or permanent migrants would need to take primacy over security concerns, without wholly dispensing with them. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade manages the PALM scheme in conjunction with a provider called the Pacific Labour Facility. Getting the administration of a much broader policy right would be immensely important.

And third, the agency of our Pacific neighbours should never be dismissed or discounted. What do they want? We have already been reminded of this in a very uncomfortable way over past months. Any new scheme needs to respect the interests of these states as well as those of the individuals who might partake in it. This consideration is as relevant to potential trade and investment reforms as it is to labour mobility arrangements.

The PALM scheme is widely seen as a solid success, as were its predecessors, though there have been noteworthy blemishes related to labour exploitation. There is certainly a base here upon which something greater could be built.

As Shoebridge acknowledged, ‘Developing, negotiating and delivering such an initiative will take all the skills [Foreign Minister Penny] Wong possesses and the buy-in of South Pacific leaders and people, along with the wider cabinet, parliament and public here in Australia.’ There’s a lot wrapped up in this set of challenges, and our historical experience might be a good guide to some of the potential pitfalls.