Climate and cash rule a crowded Pacific Islands Forum

The South Pacific lives in interesting times—a ‘crowded and complex region’ is the phrase of the moment—and the times made for an interesting Pacific Islands Forum meeting earlier this month.

Climate change roils. China pushes. Australia emphasises security. And the 18 forum members decided on a new cash formula to pay for their secretariat: Papua New Guinea showed ambition, Fiji doubled up and France stepped up.

The island leaders wrangled with Australia about climate, which was the starting point for the Nauru summit’s security declaration.

The islands listen to Australia on security, as they should; but that merely launches the discussion. To have its security perspective accepted by the islands—if not adopted—Canberra needs to mix sincerity and some sensitivity with security smarts.

The smarts thought is a reminder of the childhood lolly lesson—Smarties come in many colours, just as security has a range of hues. The leaders wore the same colour shirt for the team photo, but the Smarties rule usually rules: different colours, different preferences. The forum declaration spoke of the many shades and tones in play, describing ‘an increasingly crowded and complex region’.

Echoing the declaration, Australia’s new foreign minister, Marise Payne, dryly observed that it’s a ‘strategically crowded Southwest Pacific’, naming the external powers now crowding in as India, China, Japan, Indonesia and Russia.

In a tougher, rougher game, Australia proclaims its traditional aim to be what Senator Payne calls the ‘partner of choice’ on regional security matters, from law enforcement and the protection of rights under international law to crisis response.

The cut-through message to the islands is: take China’s cash with caution, remember the value of Canberra’s commitment.

Senator Payne pointed to the hierarchy of importance in Australia’s foreign policy white paper: ‘a resilient Pacific was clearly described as one of five fundamental policy priority objectives for Australia’. In the contest with China over interests and influence, Australia is arguing that it rates the South Pacific as a fundamental priority in a way that China never will.

As always in the South Pacific, the problem for Canberra is to maintain focus and live up to the fine words. See how that played out in the new security statement from the forum, the Boe declaration, in the first two points of the statement:

(i) We reaffirm that climate change remains the single greatest threat to the livelihoods, security and wellbeing of the peoples of the Pacific and our commitment to progress the implementation of the Paris Agreement;

(ii) We recognise an increasingly complex regional security environment driven by multifaceted security challenges, and a dynamic geopolitical environment leading to an increasingly crowded and complex region;

Australian climate denialists blithely urge an Oz desertion of the Paris Agreement on the basis that Donald Trump did it and so should we.

The denialists/skeptics need to note that for Australia, this would affect neighbourhood status as well as international standing. That first point of the Boe declaration on climate change— ‘the single greatest threat’—is a South Pacific position that Australia has signed up to, however reluctantly.

In the wrangling over the language on climate change, some Pacific nations privately accused Australia of trying to water down the final declaration. Senator Payne said she had ‘robust and frank discussions’ with her colleagues.

Making climate the first point of the security declaration was an expression of island fears and lived experience, not simply a poke at Australia. Just as the second point about the crowded and complex region describes a shared reality; it’s not just Australia expressing alarm.

‘Security’ can be rendered in rainbow hues, and the declaration offered an expanded concept:

- human security, including humanitarian assistance, to protect the rights, health and prosperity of Pacific people

- environmental and resource security

- transnational crime

- cybersecurity, to maximise protections and opportunities for Pacific infrastructure and peoples in the digital age.

Acting on its ‘top partner’ security principle, Australia is to establish a Pacific Fusion Centre ‘to strengthen information sharing and maritime domain awareness’ to get better regional responses to illegal fishing, drug trafficking and other transnational crimes.

The summit also followed the money, deciding on the budget future of its working arm, the secretariat of the Pacific Islands Forum.

The leaders agreed to increase contributions to meet 60% of the primary/core operating budget of the secretariat; and to make the first change in the way payments are shared among members since 1996, by adjusting the percentage of costs each member pays.

Australia and New Zealand currently pay more than 70% of the secretariat’s budget (35.85% each). By 2021, that’ll reduce to 24.5% each. So the kangaroo and kiwi go from paying the lion’s share of the secretariat budget to just under half. Note the symbolism of that 49% share rather than 50%—the islands certainly do.

Who steps up to pay the gap?

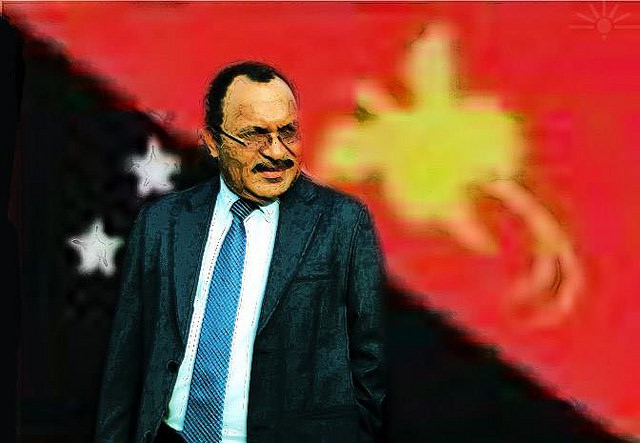

The country that’s made the most noise about kangaroo/kiwi dominance of the forum reaches into its wallet to double up: just enough to match its rhetoric. Fiji’s share goes from 2.16% to 4.35%. Fiji’s leader, Frank Bainimarama, still has nasty memories of the forum ejecting Fiji over his military takeover.

Fiji and the forum: it’s complicated. But Suva does host the secretariat. Frank will pay some more as host, and to cash up for his argument about reducing Oz/NZ control. PNG doubles its contribution with more enthusiasm (going from 5.29% to 10.66%), expressing its view of itself as the natural islands leader.

France steps up too. French Polynesia goes from 2.23% to 4.45%, while New Caledonia goes from 2.79% to 5.57%. France will pay much more than Fiji. So, in future, PNG will pay 10% of the forum budget and France, too, will pay 10%.

Lots of colour and movement as times change in a crowded Pacific.

A major

A major