Pacific security in 2025

2025 will be a big year for Pacific security as Pacific island nations grapple with upcoming elections, disaster recovery, watching the situation in New Caledonia and navigating geopolitical tensions. The Australian government will be kept busy as it seeks to remain the region’s primary security partner.

In 2024, tensions escalated into unrest in New Caledonia, many Pacific countries faced political instability, natural disasters caused devastation across the region, and Australian Foreign Affairs Minister Penny Wong declared that Australia and China are in a ‘permanent state of contest’.

Many of the same security challenges will feature in 2025, but new regional security initiatives and new governments could change how they are addressed.

In 2025, we can expect national elections in Australia, the Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru, Tonga and Vanuatu.

The Tongan and Vanuatu elections will follow political instability of late last year.

Tonga’s new prime minister, Aisake Eke, was voted in by parliament on Christmas Eve, following Siaosi Sovaleni’s resignation in the face of a looming motion of no confidence earlier in December. Eke will have less than a year to deliver before Tonga returns to the polls.

Vanuatu will hold snap national elections on 16 January after the president dissolved parliament in mid-November as a result of ongoing instability. Like most elections, people primarily will vote based on domestic issues, particularly as the country faces a lengthy rebuild of Port Vila following the December earthquake. But the election could have greater implications for regional security than usual.

Over the past few years, Australia has pursued a security agreement with Vanuatu. However, the proposed agreement has contributed to political instability and leadership change. While new leadership may present an opportunity to progress the agreement, continuing political instability may obstruct security development.

Even if the agreement remains stalled, the Australian government will have its hands full delivering on the promises it’s made across the region.

Just before Christmas, Australia made a flurry of announcements with Pacific partners—including Nauru, PNG and Solomon Islands—demonstrating its commitment to security in the region. Those agreements are in addition to commitments through Pacific owned and led regional security initiatives financed by Australia, such as the Pacific Policing Initiative (PPI) and Pacific Response Group.

The ‘permanent contest’ with China has shifted Australia’s approach to Pacific policy. In making agreements, Canberra has started adding conditions that support government’s aim of being the region’s primary security partner.

Agreements with Nauru and PNG, as well as the Tuvalu–Australia Falepili Union, have shown that Australia wants to ensure that its efforts, investments and infrastructure are adequately secured. In 2025 and beyond, Australia should ensure these agreements are transparent—for example, by detailing the strings attached to the deal to create a PNG team for Australia’s National Rugby League. This would set Australia apart from others, such as China, which still hasn’t made public any details of its 2022 security agreement with Solomon Islands.

Unfortunately, natural disasters and environmental challenges are almost certain in 2025. Humanitarian aid and disaster relief operations will be necessary as we approach the peak of the 2024–25 high-risk weather season.

The Pacific Response Group should provide a platform for regional military coordination on disaster response, but there’s still plenty of work to be done to show how it will interact with civilian or regional relief mechanisms, such as the PPI.

Competition with China is likely to continue to creep into this space, and those wary of China’s influence will be watching the use of aid in the battle for hearts and minds.

New Caledonia will also remain on the radar of many, with little progress being made on political negotiations. Political instability in Noumea and Paris is affecting efforts to recover from the 2024 riots. Pacific nations are ready to support New Caledonia and, if progress isn’t made before the Pacific Islands Forum this year, additional missions to the French overseas territory could occur.

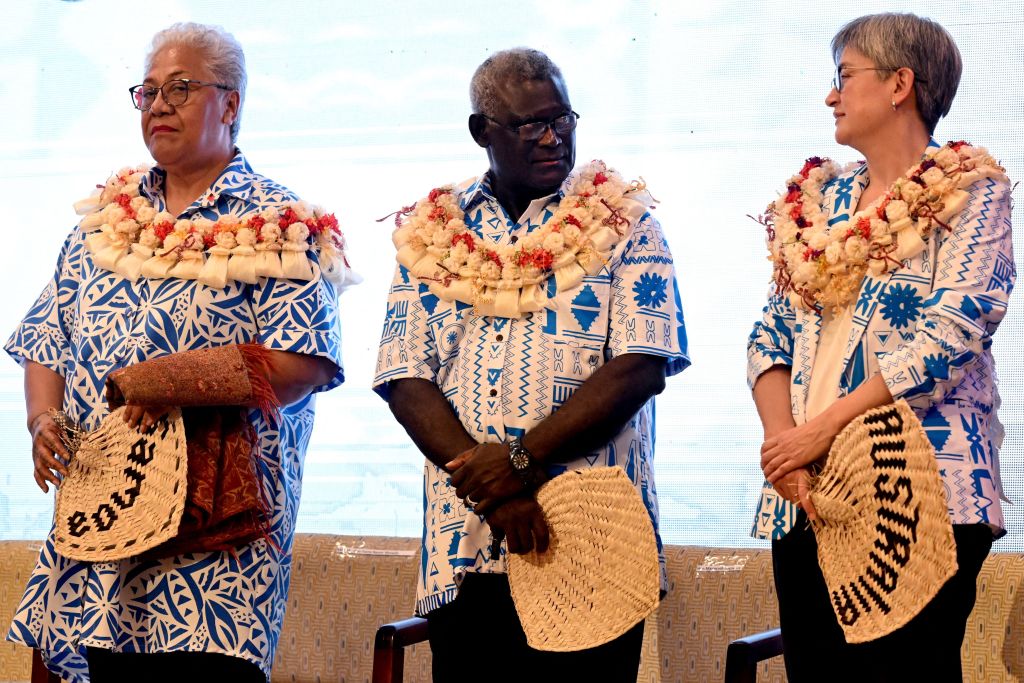

Many eyes will be on the Pacific Islands Forum Leaders Meeting, to be hosted by Solomon Islands in September. Positive security outcomes of last year’s meeting, including endorsement of the PPI, were overshadowed by a controversial change in recognition of Taiwan in an official statement. China is likely to further push Pacific nations to cut ties with Taiwan and undermine its legitimacy in regional forums, and Honiara might be more lenient towards Chinese pressure.

Pacific countries will have to ensure their voices are heard when navigating these tensions. To this end, Fiji and Vanuatu released their first foreign policy white papers last year, and in April PNG will table its first since 1981.

In September, PNG will celebrate its 50th anniversary of independence, so the month will be busy for Pacific leaders. Development partners will seek to capitalise on the occasion, making large announcements in partnership with PNG.

Very few of the events in 2024 could have been accurately predicted, including leadership changes, unrest and disasters. This year will be no exception, and the region and its partners must be ready, as always, to adapt.