A hydrogen bomb fits North Korean nuclear strategy so perfectly that it’s likely to be a top priority program. Most discussion of North Korea’s nuclear effort focuses on matters of “can and when”. Can they miniaturise a nuclear weapon? Can they marry it to a missile? Can they build an ICBM that will reach the United States?

Those are obviously important questions. But they don’t cover another fundamental question. What difference would it make if North Korea was to get a hydrogen bomb?

A hydrogen (fusion) bomb is a lot more powerful than a fission weapon of the type the DPRK has tested to date. It’s more complicated to make, too. That complexity adds to the status of the achievement. An H-bomb is a significant technological accomplishment. It took the United States seven years after Hiroshima to achieve it, and it took the efforts of the country’s top scientists, including Edward Teller, Stan Ulam and John von Neumann. That gave it a star quality of national achievement.

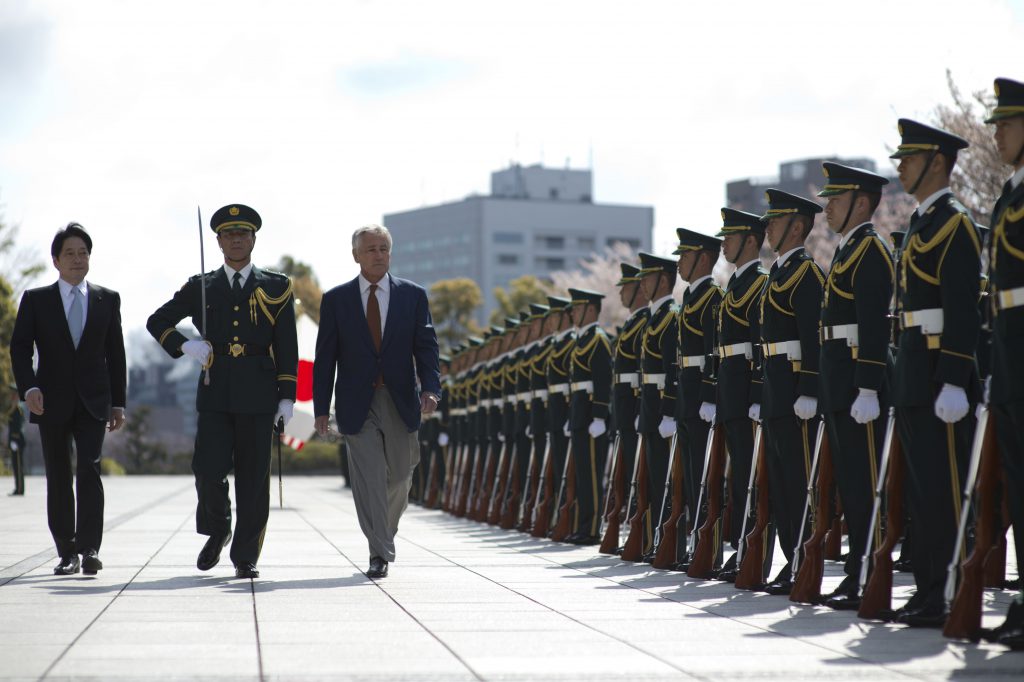

It was also a reason China went all out to get an H-bomb too. It took them only three years following their first nuclear test in 1964 to get one. Given that the Soviets had cut them off from technology know-how years before, and the deterioration of Chinese science and technology during the Maoist era, it was an extraordinary achievement with significant domestic and international consequences. Think of how careful and risk averse that made the United States in Vietnam. Big escalation strategies were taken off the table.

What difference would a North Korean H-bomb make? My sense is that it would make a big domestic difference in North Korea, which would become the only country not in the official nuclear club of the NPT ‘haves’ and the Permanent 5 of the United Nations with a hydrogen bomb. It’d be quite an achievement for a small destitute country, and would certainly be touted at home as a sign of national accomplishment. It would provide some badly needed solidification for the regime.

An H-bomb would have big impacts on foreign policy as well. Strategies aimed at North Korea involving sanctions, blockades, financial warfare or cyber-attacks might look quite different with several hydrogen bombs in the mix. When the consequences of an eruption of violence become so stark, they also become crystal clear. With 20–30 fission bombs and a handful of hydrogen bombs, it becomes impossible not to ask the question as to where things might go in the event of escalation. What if sanctions drive North Korea into famine, or if financial attacks bankrupt the elite? What happens next? To a risk averse China, and even more cautious neighbours, bellicose demands by Washington to ’confront evil in Pyongyang’ will look even more dangerous than they do now.

Today North Korea has a nuclear force that’s objectively more powerful than China had in the 1960s. Add an H-bomb to its arsenal and the North’s potential for devastating attacks becomes unambiguous. No one is going to go too far to pressure this regime. Any plan to attack it with conventional precision strikes will always generate the question, ’What if we miss some of the nuclear missiles?’. Now add to that ‘What if we miss one of the H-bombs?’.

An H-bomb will have an especially significant impact on the North’s command and control. They’re now moving to a system of mobile launchers, on land-based missile carriers and submarines. Command and control of a mobile nuclear force is quite complicated. It requires marrying warheads to launchers, assurance that the ‘go’ order gets through, and backup command centres in case the original ones are destroyed. It also means pre-delegated launch authority disseminated in case the high command is destroyed.

There are several problems here. One is the ‘coup risk’, something we know has been a consuming issue for the Kim family for generations. There’s extreme compartmentation and surveillance to prevent it. A rogue group of North Korean officers that gets physical control of a hydrogen bomb would possess the premier symbol of national power. In the unpredictable circumstances of internal disorder it cannot be ruled out that this device might actually be used—or detonated to prevent it from falling into wrong hands.

That leads to a second command and control problem. The lack of experience in handling nuclear arms means that moving them around the country on mobile launchers could produce an accidental firing. It could be an accidental launch at Japan. Or, more likely, it could result in an accident on North Korean soil. Here’s where an H-bomb matters. A ground burst H-bomb would produce far more radioactive fallout than a small, fission bomb. A hydrogen bomb would rain fallout on Japan, South Korea, and, days later, the United States.

With its enormous killing radius, an H-bomb turns what is today a dangerous nuclear threat from North Korea into the powder keg of Northeast Asia. The image of the Balkans in the early 1900s was of a great game of grand strategy played by the big powers. That was replaced by one where the whole region became a keg of TNT, one with convoluted strategy risks that could spark the eruption. The game had changed, fundamentally, as diplomats saw in 1914.