Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

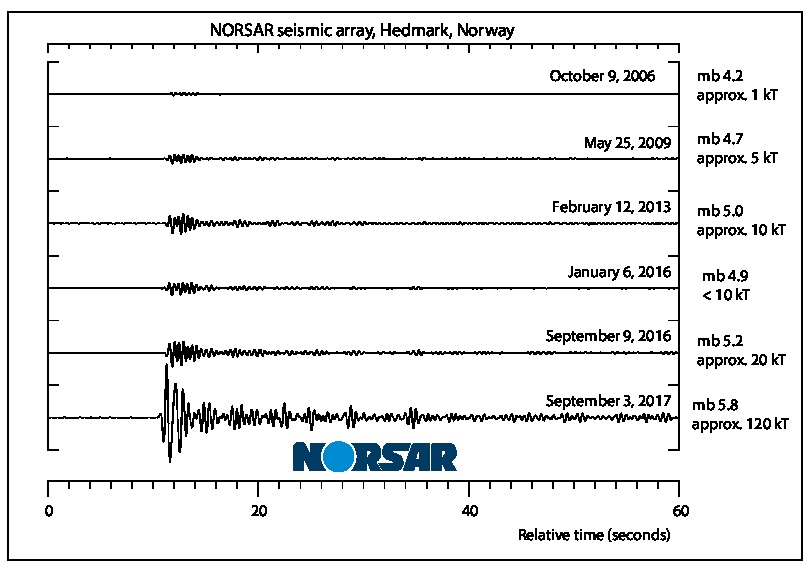

North Korea’s sixth nuclear test is easily its most impressive. The fifth—in September last year—involved the detonation of a device similar in yield to the bomb the Americans dropped on Hiroshima in 1945. The latest test features a substantially larger yield. Seismic signals are an imperfect indicator, but estimates currently range from about 70 kilotons all the way up to about 500 kilotons. It’s possible, but not certain, that the test featured a genuine thermonuclear device, a second-generation nuclear-weapon design in which a primary fission explosion ignites a secondary fusion stage. If any radionuclides have leaked from the test site, we’ll get a better picture of the explosion, but that could be some weeks away.

Still, the big conclusions are relatively straightforward. First, North Korea’s nuclear capabilities are no longer constrained to the detonation of relatively low-yield fission devices. The days are over when we could depict the North Korean nuclear program as merely the equivalent of the US program in 1945. Second, when the results from the sixth nuclear test are placed alongside the large strides that Pyongyang has made recently in ballistic-missile development, we’re fast approaching a crunch point where something must be done to corral the North’s nuclear arsenal. A fresh bout of hand-wringing and garment-rending—even another bout of sanctions—is probably not going to give us much leverage on the problem.

Each test, whether of missile or nuclear weapon, gradually builds North Korea’s capacities. True, none of the individual tests is a back-breaker by itself. But the broader programs are breaking the back of global and regional order. That’s because a North Korea equipped with nuclear-armed ICBMs is simply unacceptable. It’s unacceptable at the global level because a pariah state can’t be allowed to hold a sword over the head of the international community. And at the regional level, an emboldened North Korea will destabilise Northeast Asia—corroding the US’s Asian alliances and likely begetting a new wave of proliferation by latent nuclear states.

In brief, if North Korea keeps going down the path it’s currently taking, the outcomes are intolerable. A North Korea that had a slow-moving nuclear-weapons program boasting only limited reach was a tolerable threat. Regional nuclear competitions are relatively common—not to the point where we can become blasé about them, true, but still relatively common. Today’s North Korea has morphed into something much more deadly. It’s the sole nuclear-armed state outside the P5 that seeks intercontinental-range destructive capabilities. And yet it’s the nuclear-armed non-P5 state with the least equity in the international order.

Some argue that North Korea seeks nuclear weapons because of insecurity; that it’s fear of attack and invasion that’s the principal driver of Pyongyang’s WMD programs. Frankly, that argument’s not convincing. Security concerns might be sufficient to drive a small nuclear-weapons program, but not the one that now confronts us. Rather, Pyongyang seeks nuclear weapons as a status symbol, as the price of entry to the only one of the world’s exclusive clubs to which it might actually gain admittance. ICBM-equipped nuclear powers number only four: the US, Russia, China and North Korea. Kim Jong-un seeks international recognition on the basis of the only achievement his regime can boast—the development of a capability to pull down the global order on a day of his choosing.

Reversing that development is now an issue of urgency. I’d like to think that doing so might offer an occasion for international cooperation, because responsible great powers should share the judgement that having intercontinental-range nuclear weapons in the hands of a pariah state is an unacceptable condition. Still, the prevailing geopolitical winds scarcely seem conducive to such an outcome. And there’s a fair degree of slack in the steering wheel of US global leadership with President Trump in the White House.

But if we’re prepared to admit North Korea into the ranks of the world’s ICBM-equipped states, what’s the basis for denying that status to any future proliferator? Some years back, Robert O’Neill observed that ‘the bomb’ had successfully escaped the hands of first the superpowers, and then the great powers, to come to rest in the hands of the world’s underdogs. Accepting that the underdogs can wreak nuclear havoc at intercontinental ranges seems to drag us even closer to the abyss.

In one important respect, of course, nothing has changed after the sixth nuclear test: we still don’t have any easy options for reversing North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs. Kinetic options look costly, non-kinetic options ineffective. But doing nothing will be worse. A crisis postponed is not necessarily a crisis averted. A future North Korea would have more and better nuclear warheads, greater numbers of delivery vehicles, and proven nuclear technologies ready to be sold to the highest bidder.

North Korea’s sixth—and most powerful—nuclear test is part of a pattern of escalating belligerence. As a result, the UN Security Council will issue yet another resolution condemning Kim Jong-un’s blatant violations of previous council resolutions. And it will set out to impose yet another round of sanctions on the hermit kingdom. Calls for a tougher response, including even a pre-emptive strike on Pyongyang, will grow louder.

How will President Trump react? Truth be told, he doesn’t have much room to manoeuvre.

Any effort to lavish attention on Pyongyang and offer it political and economic favours would be as foolish as it is unlikely. Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush tried that approach, which just handed North Korea a string of bribes in exchange for ending its provocations, suspending its nuclear activities and entering diplomatic talks.

In each case, however, Pyongyang failed to fulfil its commitments and eventually returned to producing weapons, testing missiles and escalating the war of words with Washington and its allies. So diplomacy won’t work, at least for now.

But neither is there any viable military option available. A pre-emptive strike against Pyongyang may provoke the very action it’s designed to prevent. North Korea has nuclear weapons, which the regime can use. It still has formidable conventional artillery, which it can use to hit Seoul. A US strike against North Korea would be unlikely to have the support of America’s key Asian allies. But China would come to the North’s rescue, and there’s no telling where that would lead.

Nor is Beijing much help in coercing Pyongyang into giving up its nukes. China needs North Korea for geopolitical reasons. The collapse of the regime would spark a refugee crisis and probably unite the Korean peninsula under the US security umbrella. If you think Russia is too sensitive about a Western bulwark on its doorstep, how do you think China would respond to a Western bulwark in its own sphere of influence? Remember that China entered the Korean War in late 1950 when US-led forces moved towards its border. Beijing has no interest in seeing North Korea collapse, so China’s leaders aren’t in a position to get tough with Kim.

That’s not to say that China’s leaders like how their communist comrade’s sabre rattles. They don’t. It only antagonises Washington and its allies, might cause Japan to go nuclear, and has led the US to put the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system in South Korea—all of which Beijing doesn’t like at all. Nor is it to say that the Chinese leaders want to keep Kim in power. They’d probably like to replace him with someone whose behaviour is more restrained. But they are committed to keeping North Korea intact, which gives them little leverage in their dealings with Pyongyang.

So what now? How best to deal with a nuclear North Korea?

A starting point is to recognise that, from Pyongyang’s perspective, it makes eminently good sense to have nuclear weapons. Northeast Asia has long been a dangerous place and thus it’s no accident that Korea disappeared from the map for the first half of the 20th century. North Korea is a minor power surrounded by three major powers—China, Japan and Russia—and with an outside power—the US—that has threatened it with regime change. Nuclear weapons are the ultimate deterrent. Moreover, when the US does things like striking Syria, as it did in April, or helping topple Saddam Hussein in 2003 or Colonel Qaddafi in 2011, it gives Pyongyang a very powerful incentive to keep its nuclear weapons.

It’s commonplace in the West to say that Kim Jong-un is crazy, mainly because he has nuclear weapons. That is not persuasive. He is a brutal dictator and his conduct, especially in recent months, has been reckless. But he is neither irrational nor suicidal. His primary interest is to ensure the survival of his regime. Why then expect him to go gently when he has nothing left to lose? The only way to give him an incentive to hold back is to give him the chance to survive.

If there’s no way to disarm North Korea, what to do? The only plausible policy response is one of containment and deterrence.

It worked against Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union and Mao Zedong’s ‘Red China’ at the height of the Cold War. It has also worked against North Korea since its first nuclear test in 2006. Although containment can’t work against terrorists, who can run and hide, rogue states are different: they have a mailing address. And if North Korea used nuclear weapons against US interests in the region, it would guarantee massive retaliation, probably obliteration.

It was not President Trump, but President Clinton who warned on the demilitarised zone in 1993 that if the North Koreans ever used nuclear weapons, ‘it would be the end of their country’. That strategy remains the only viable option in dealing with North Korea: a strong and clear deterrent threat carries risks, but it is riskier to invite precisely the threat that we wish to prevent.

With every tweet or meeting with a foreign leader that US President Donald Trump completes, American officials find themselves struggling to reassure allies that the United States remains committed to their security. Nowhere is this truer than in Asia, where longstanding US strategic engagement, backed up by the world’s most advanced military, has maintained the balance of power for decades.

Trump’s signature Asia policy—his pledge to stop North Korea’s development of nuclear weapons—should be a clear-cut example of American military resolve. Unfortunately for the region, it has proved to be anything but that.

In early June, Defense Secretary James Mattis tried his best to convince Asian counterparts gathered in Singapore that US support was unwavering. The presence of two US aircraft carriers off the Korean Peninsula—the first time in 20 years that US naval maneuvers included two carrier groups—was meant as a ‘message of reassurance’ against any aggression by North Korea.

But neither Mattis’s speech, nor the muscle flexing at sea, did much to bolster US credibility in South Korea, or to restrain the North’s nuclear ambitions. The problem wasn’t Mattis’s speechwriters, or the US Navy’s ‘show the flag’ naval exercise. It was Trump himself.

From threatening military strikes on the North while all but inviting Kim Jong-un to a Mar-a-Lago tête-à-tête, to threatening to tear up trade and defense pacts with South Korea, Trump has thoroughly confused America’s Asian allies. The effects of his contradictory statements will come home to roost later this month, when South Korean President Moon Jae-in visits Washington, DC. Moon is crafting his own approach to dealing with Kim, while Trump’s behavior could hardly be undermining US influence more.

Moon’s desire to take a different tack with the North should come as no surprise. A long-time advocate of a softer line, he acknowledges the North Korean threat, but believes that the South has time to seek a solution by reviving economic ties and dialogue. The strategy harks back to the South Korea’s decade-old ‘Sunshine Policy,’ former president Roh Moo-hyun’s unsuccessful outreach to the North, which Moon supported. Today, Moon is entertaining a range of similar ‘soft’ options—such as reducing military tensions, increasing people-to-people contacts, and offering more humanitarian aid—to help shift course gradually.

More fundamentally, Moon believes that the US has steered the alliance’s North Korea strategy off course. He wants South Korea to be in the driver’s seat, with his government as mediator between the US and North Korea. Moon laid down his marker on June 7, when he announced a freeze on deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) US anti-missile system in South Korea, because of his questions about allied decision-making. The freeze, which includes an ‘environmental review,’ is a none-too-veiled signal to expect more assertiveness on national security and North Korea policy.

Moon is well positioned to capitalize on Trump’s self-inflicted wounds—which have included threats of unilateral military action, protectionist mantras, and the abandonment of the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement. Moon, who was elected to boost jobs and curb corruption, campaigned on sweeping away his predecessor’s policies, including her hardline approach toward North Korea. Even if sparks fly in Washington later this month, Moon is unlikely to pay a political price at home. South Koreans broadly support a strong relationship with the US. But they also follow American politics closely, and these days, many regard the dangers of erratic leadership as no longer being confined to Kim’s regime.

Indeed, Trump’s statements about the US-South Korean relationship have ranged from the impolitic to the bizarre—such as accusing the South of unfair trade deals and then threatening to send South Korean leaders a bill for the THAAD system. He has also issued unnerving military pronouncements, like an April prediction of a possible ‘major, major conflict‘ on the peninsula. Those comments, made during an interview with Reuters, seemed to overlook the deployment of 700,000 North Korean soldiers just above the demilitarized zone, which would make any war with the North devastating to the South.

Trump’s approach to the nuclear crisis on the Korean peninsula has produced equally troubling knock-on effects. China, South Korea’s leading trade partner, is a case in point. With South Korea’s economy struggling to sustain growth, China is leveraging its position by registering its opposition to THAAD. Calling the system a threat, the Chinese have been boycotting South Korean goods, stalling investment, and curbing what had been a booming tourist trade.

How hard Moon presses Trump for a different approach to North Korea remains to be seen, but one thing is certain: Trump’s standing among South Koreans won’t be what keeps Moon mum. According to the Asan Institute for Policy Studies, a Seoul-based think tank, Koreans gave Trump exceptionally low approval ratings during his 2016 presidential campaign, and his popularity remains at rock-bottom levels. Even with China’s recent THAAD-related arm-twisting, Chinese President Xi Jinping rates more favorably among South Koreans than Trump.

Moon will have many questions for Trump about US leadership in Asia—questions that Mattis was unable to answer. Given the risks posed by an unpredictable US president, South Koreans’ unease is easy to understand. Before Trump, 11 US presidents helped maintain stability on the Korean peninsula by building alliances, using diplomacy, calibrating their rhetoric, and deploying American military strength. Since the end of the Korean War, no president has even casually, much less flippantly, called the US role on the peninsula into question. None, that is, until now.

Vietnam’s Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc has just concluded a visit to the United States to meet the president and negotiate a way forward on trade and the South China Sea—two issues central to Vietnam. In the end the South China Sea took a backseat to trade. North Korea also proved to be a major talking point. Washington has been seeking support to pressure North Korea to drop its nuclear and missile programs.

Hanoi has condemned all North Korean missile tests and stated on 30 May, a day after Phuc arrived in Washington, that it was ‘deeply concerned’ that the DPRK was ‘violating relevant resolutions of the UN Security Council. Viet Nam consistently supports all efforts aiming to promote dialogue and maintain peace and stability on the Korean Peninsula.’

Until the USN’s recent FON patrol, Vietnam worried that the SCS might be taking a permanent backseat to the DPRK in Washington’s regional discussions, allowing greater Chinese hegemony in return for help on North Korea. Hanoi steadfastly maintains that UNCLOS should be the guiding principle, and it also values a strong US American deterrent presence there. That reference to the UN and international norms shows its ongoing commitment to multilateralism and the UN (when it suits—human rights and freedom of religion, not so much).

The idea that Hanoi could help with North Korea, possibly using its old (though frayed) ties to begin discussions, popped up at The Huffington Post. But the author, who said the idea had been floated in Vietnam, didn’t attribute provenance. (Another writer at The Diplomat suggested the same thing last year.)

Were it possible, it would be a great coup for Hanoi and would help bring Vietnam, China and the US together. And it wouldn’t be the first time in that kind of role: Vietnam also hosted reconciliation talks between North Korea and Japan some years before.

Superficially, Vietnam could be a sensible choice. Both communist nations fought a civil war and against the United States, both under charismatic leaders. But there are also stark differences—not just of hardline communism versus the type that lets McDonalds in. It’s also a difference in foreign policy, between isolationism and multilateralism, ‘more friends and fewer enemies’ versus… mostly enemies. The difference in leadership is profound too: between a hereditary communist leadership, and a model that favours consensus among Politburo members.

Yet North Korea was a watcher of Vietnam’s post-war renovation and its 1975 reunification. In 2007 then PM Kim Yong-il visited, flying in on an old Tupolev plane, which the BBC described as the kind of ‘bleak reminder’ of a time before the country modernised.

‘I think there is currently great interest in North Korea in Vietnam’s way of economic reform,’ Hwang Gwi-yeon, a professor in international relations at the Pusan University of Foreign Studies, South Korea, told the BBC at the time. ‘The situation in North Korea is similar to that in Vietnam many years ago and Vietnam has provided a very suitable model of development.’ Vietnam’s command economy capitalism was exciting to North Korea, coming a few years after it had tentatively tried its own version of a Chinese-style Special Administrative Region that went awry.

Those ideas are 10 years old, and haven’t made much of a resurgence under Kim Jong-un. Instead, things have atrophied further, despite Vietnam’s support for North Korea’s membership of the ASEAN Regional Forum. North Korea’s failure to pay for a large shipment of rice in 1996 set ties back, making the old comrade seem unreliable. Vietnam isn’t in the Chinese position of having to prop up the regime, and it doesn’t have as much to worry about regarding a huge influx of refugees, though it has been part of the Southeast Asian route out, and flew a large group out to South Korea in 2004.

A 2006 International Crisis Group report, which looked at the plight of North Korean refugees around the world, noted that Vietnam apparently regarded the relationship as ‘a burden’ at times, and required North Korean officials traveling to Vietnam on Hanoi’s coin to take a train. The report observed that

‘…since 2004, when South Korea took hundreds of North Korean refugees from Vietnam to Seoul, Vietnam has been especially cautious to avoid the risk of having to publicly choose between Pyongyang and Seoul.’

Vietnam’s ties with South Korea are strong, though largely business-based, despite having established a ‘strategic partnership’. Seoul made vague overtures about Vietnamese support regarding North Korea earlier this year, even as Vietnam wondered about more South Korean support in the South China Sea. Most analysts tend to think that as ties with South Korea—by far the largest investor in Vietnam—have progressed, friendship with the North has fallen by the wayside. But those residual ties might have some value, and any brokering by Vietnam would be very well received by the US, China and South Korea, especially under the more liberal leader Moon Jae-in, who values the idea of dialogue with the North.

The notion of Hanoi as broker between Washington and Pyongyang has great symbolic value for Washington: the former enemy is now moving so fast towards capitalism that its Prime Minister goes to Washington to promote free trade to the US President, while working the middle ground to bring peace and stability. And Vietnam, which is always looking for useful ways to improve its world role and its ties, would also benefit greatly.

Australia has only one agreement that automatically commits us to war and it isn’t ANZUS. At the signing of the armistice in Korea in 1953 we agreed, with South Korea’s allies, that we would defend the South in the event of an attack by the North. It had nothing to do with the US alliance, but rather is a UN commitment. It was associated with a set of non-aggression pacts which were repudiated by North Korea in 2013. At that time a UN spokesperson said the pacts couldn’t be unilaterally repudiated under terms registered with the UN and that Pyongyang was considered bound. The stakes for Australia are high indeed.

President Trump has been gripped by the North Koreans’ steady progress towards an ICBM that could reach the continental US. His ‘never going to happen’ pledge publicly established a ‘red line’; it will be a litmus test of his credibility. The issue’s unique status is underlined by the president’s apparent willingness to read all related briefs and intelligence reports. If diplomatic efforts, ramped up sanctions and Chinese persuasion fail, then Trump has made clear that military options will be seriously considered.

The Trump red line hasn’t been extended to shorter range missiles or the nuclear program generally. However, military pre-emption associated with it would significantly raise the prospect of a North Korean response making consideration of even broader pre-emption necessary. That could spell devastation for South Korea and cause massive damage both to Japan and to US bases in Japan and Guam. A major war would result; minimising those consequences would be the main task for the allied military. A subsequent North Korean attack on the South would engage Australia’s 1953 armistice obligations.

Trump’s red line is drawn on a situation Asia understands well. He has put American credibility on the line. To the North Koreans he has said that he would be ‘honoured’ to engage Kim Jong-un in discussions on nuclear matters, making clear that regime change in Pyongyang isn’t on his agenda. Nonetheless, North Korea presses on.

With the Chinese, Trump has deployed a range of carrots and sticks, all of which carry their own implications in the minds of Asian leaders. The stick is that China, a longstanding enabler of North Korea’s program, faces the prospect of a war on its border and a harsher American attitude on bilateral issues. The carrots have been extraordinary: a walk-back on Taiwan, a trade agreement, a retreat from freedom-of-navigation patrols in the South China Sea, and an effective enhancement of China’s regional status (the opposite of Trump’s stated intention in the presidential election campaign).

Despite paying close attention to briefings, Trump appears not to have grasped the regional context. The ally most affected is South Korea. Seoul has been roiled by an apparent presidential indifference to South Korea’s fate in all this. Nothing the president has done has allayed local concerns at what they call the ‘Trump risk’.

Consider here the extraordinary series of comments and initiatives by Trump in the last month of the South Korean presidential campaign. First was the announcement that a carrier task force—an ‘armada’ in his words—has been dispatched as a signal that Pyongyang’s actions could draw a military response. Fear, then ridicule, was the reaction in South Korea when its appearance was delayed.

Second, Trump erroneously opined that South Korea had once been occupied by China, reinforcing a South Korean view that he knew nothing about them. He also indicated that it might be necessary to renegotiate or repudiate the US–ROK free trade treaty.

Finally, having deployed the THAAD missile defence system—a controversial move in South Korea and heavily related to the defence of American troops in the region—Trump claimed that South Korea should pay. All of Trump’s interventions roiled a South Korean presidential election campaign in which Moon Jae-in, the overwhelming winner, sought to reset the Seoul–Pyongyang dynamic.

The risks of a pre-emptive strike are acceptable to Trump. However, the red line is limited. A freeze of the contemporary position with strong verification might just be possible (though it isn’t on the table currently). Such a deal would stop North Korea’s nuclear weapons program short of an ICBM, but it would massively complicate the global non-proliferation regime. The Iran deal was doable in part because Tehran’s public position was that it didn’t want a nuclear weapon. Kim Jong-un is way beyond that. Fig leaves would be necessary. Somehow North Korea’s six-party commitment not to proceed to a nuclear weapon would have to be in any agreement.

China will underperform. Beijing won’t get the North Koreans to a complete rollback or to a negotiation focused on achieving that goal, so vital to the non-proliferation regime. It isn’t vital to Trump, who is overwhelmingly motivated by perception. North Korea not proceeding with an ICBM gets him there domestically.

For the rest of the region, it’s important to cool the situation. Lessons, however, have been drawn. South Korea, Japan and Taiwan are developing their own local defences and defence industries. This experience will accelerate that trend. Lessening dependence on the US military is now on the agenda in all three countries. But that is long term.

In the meantime, the trio seek breathing space. Return the US deterrent to a latent status. It shouldn’t be at the forefront of diplomacy but credible enough should Pyongyang consider a more active approach to its nuclear ambitions. Seoul, Tokyo and Taipei now hope they can lift the threshold of that eventuality.

Later today US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson will preside over a ministerial-level meeting of the UN Security Council on North Korea. Most observers will closely focus on Tillerson’s remarks, yet there’s no doubt that China—Pyongyang’s ally—has a pivotal role in diffusing tensions.

Amid the US sabre-rattling with its allies in the region and calls for renewed dialogue, China has been seeking to ensure a solution to the escalating tension remains within the purview of the UN. This is by no means surprising on China’s part—it’d prefer a resolution of the situation that halts North Korea’s nuclear program but maintains the regime in Pyongyang.

Beijing also wants a solution that results in the US reducing its military engagement in the region. Enhanced sanctions are more likely to deliver these outcomes than military action. Although the US leads on North Korea in the Council, it works bilaterally with China before sharing any draft resolution with the wider Council membership. So China’s strategic interests are best served by ensuring that the Security Council continues to manage the crisis on the peninsula. And it has an interest in undertaking a constructive role in any negotiations taking place.

‘China’ and ‘constructive’ are two words not usually seen together in a UN context. Beijing’s actions in the South China Sea, along with its voting pattern of siding with Russia to veto international efforts aimed at resolving the conflict in Syria, lend weight to China’s obstructionist profile when it comes to the UN or upholding the rules-based global order.

China refrains from taking on any ‘pen-holder’ responsibilities on the Council, relying on the P3 (the US, UK and France) to do the heavy lifting when it comes to drafting resolutions, mandates and Council responses. It has also frequently sided with Russia on issues that are likely to interfere with state sovereignty. Both countries unsuccessfully tried to obstruct efforts to put the human rights situation in North Korea on the Council’s agenda. When it was an elected member in 2014, Australia creatively drew on the Council’s own rules to use a procedural motion—which can’t be vetoed— to add the item to the Council’s agenda.

Still it’s worth noting that China’s position hasn’t always aligned with Russia’s on the Council. It took a noticeably different stance when it came to recent US missile strikes in Syria. Unexpectedly it didn’t rail against the interference in national sovereignty. Nor did it join Russia in vetoing recent attempts to adopt a resolution condemning the recent chemical weapons attack in Syria. While it’s difficult to identify the rationale, it’s fair to surmise that China’s engagement with the UN continues to evolve. One obvious aspect of this shift is in the area of UN peacekeeping, where it has growing interests.

China’s currently the largest troop and police contributor among the P5, with over 2,500 personnel deployed on 10 peacekeeping missions. While that number has dropped from a historic high of over 3,000 during 2015, China still ranks 12th on the list of countries contributing military and police personnel. President Xi also pledged 8,000 standby troops to the UN at a summit hosted by then President Obama in September 2015. China surpassed Japan in 2016 to become the second largest assessed financial contributor to the UN peacekeeping budget, currently paying 10.29% of the US$7.87 billion funding.

Like most countries, China’s engagement in UN peacekeeping isn’t purely altruistic. Most of its personnel are deployed on the African continent, where there’s significant overlap with China’s strategic interests. It has investments in the oil fields in South Sudan, where it has its largest deployment of personnel to any UN mission.

China’s in a unique position of influence: it has a permanent voice at the table that mandates and authorises operations, it has authority in budgetary negotiations about peacekeeping in the UN General Assembly’s Fifth Committee, and it has legitimacy within the community of major troop and police contributors, which often claims to go unheard in the council. China has been rumoured to be interested in the key post of head of UN peacekeeping, a position that the French have held for over 20 years, leveraging influence over the direction of UN peacekeeping policy.

Secretary-General Antonio Guterres will find it increasingly difficult to ignore China’s desire to have more influence in the UN system. Beijing has the political, financial and operational credentials to add weight to its position within the organisation’s peace and security architecture. And that may increase if the US, UK and France succumb to political pressure to focus on their own domestic concerns.

The Security Council discussions later today will show that North Korea is an issue where the UN can serve China’s interests, as well as those of the international community. As the world’s second largest economic and military spending power, China doesn’t need to rely on the UN to pursue its national interests. The North Korean issue serves as a reminder that it has many diverse reasons to constructively engage.

Connecting the strategic dots between Afghanistan, Syria, and North Korea has become an unavoidable task. Only by doing so can the world begin to discern something resembling a coherent, if misguided, approach to US foreign policy by President Donald Trump’s administration.

Start with the military strike on the airfield in Syria from which a chemical attack was launched by Bashar al-Assad’s regime. Was the barrage of Tomahawk missiles intended simply to send a message, as the Trump administration claims? Does it suggest a more interventionist approach to Syria’s seemingly intractable civil war?

One might wonder if that strike indicates a more muscular foreign policy in general. Shortly afterwards, the US military, having received ‘total authorization’ for action from its commander-in-chief, dropped a massive ordinance air blast (MOAB) bomb—the largest non-nuclear bomb in the US arsenal—on Afghanistan. The immediate goal was to destroy a tunnel network being used by the Islamic State. The question is whether that is all the MOAB was meant for. North Korea’s penchant for burying its military installations deep underground is well known.

Already, Trump has ordered a US Navy aircraft carrier group to sail to waters off the Korean Peninsula, amid rising tensions over the North’s nuclear and missile tests. In this context, it seems that former President Barack Obama’s policy of ‘strategic patience’ toward North Korea may be about to be replaced.

But while Trump is leaning on spectacular displays of hard power more than Obama did, he seems not to have settled on any overarching diplomatic approach. After eagerly sending Obama’s diplomatic appointees packing on Inauguration Day, Trump has yet to fill key posts, including US ambassadors to South Korea, Japan, and China.

Whatever modicum of diplomacy there is—such as Trump’s recent summit with Chinese President Xi Jinping—seems to exist only to support military solutions. It should be the other way around: military force should be used to support diplomacy. As the Prussian General Carl von Clausewitz famously observed, war is a serious means to a serious end.

Consider the situation in Afghanistan. The late Richard Holbrooke, arguably America’s greatest diplomat at the turn of this century, sought to negotiate with Taliban insurgents. Though not all Afghan Taliban would be open to talks, he believed that enough of them could be engaged and pacified to weaken the most extreme factions. His was a smart strategic approach that goes back to the Roman Empire: ‘divide and conquer.’

The US military under Trump, by contrast, dropped the ‘mother of all bombs.’ It may be that the Trump administration envisions a unilateral withdrawal from Afghanistan, as the Obama administration once did. Under Trump, however, the US may drop a few more MOABs on the way out.

The Trump administration seems to be aligning with its predecessor on another strategic goal: the removal of Syria’s Assad from power. But what would come next? Would the Sunni Islamists who comprise the majority of the opposition on the ground really just turn in their weapons, shrug off all that pesky extremism, and embrace life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness under a democratic government?

In any case, we may never find out, because Assad is still winning. He has the support of powerful allies, including Russia and Iran, and the opposition is hopelessly divided. Even the Free Syrian Army is really several armies that have little prospect of unifying—and even less hope of toppling the regime. The most plausible option for ending the fighting in Syria is US engagement with global powers—including Assad’s allies—that agree on the need for a diplomatic settlement, based on power sharing and decentralisation of government.

North Korea also suffers from an autocratic leader with no plans to go anywhere. But, unlike Assad, Kim Jong-un could detonate another nuclear device any day now.

Yet here, too, there are constraints on what a military approach can achieve, though that didn’t stop Vice President Mike Pence from saying recently that ‘all options are on the table.’ For his part, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson spent all of his time on the ground in South Korea last month with the US military commander there, rather than visiting with his own employees: the diplomats posted at the US embassy.

Senator Lindsey Graham has gone so far as to recommend launching a strike against North Korea now—before the regime can develop the missiles needed to deliver nuclear weapons to the US. No matter, apparently, that the North can deliver them to its southern neighbor. Graham considers himself a pragmatist; but there is nothing pragmatic about destroying the trust that underpins the US-South Korea alliance.

Few in the US seem to have Graham’s stomach for military action that would put 20 million South Koreans in imminent danger. Some advocate making a deal with the Kim regime: a moratorium on weapons tests, in exchange for curtailment of US-South Korea military exercises. But that approach would also weaken America’s critical alliance with the South—albeit less severely—while doing nothing to suppress the North’s appetite for nuclear weapons.

The circumstances in Syria, Afghanistan, and North Korea vary widely, but they have some things in common. All represent serious foreign-policy challenges for the Trump administration. And none can be resolved without comprehensive diplomatic strategies.

It is often said that 80% of life is just showing up. In diplomacy, however, the key is following up, in order to transform senior policymakers’ overarching vision into a coherent strategy that gives structure to the day-to-day work of protecting the interests of the US and its allies around the world. That is not something that the military can do alone.

A senior US military general in South Korea recently advised Foreign Minister Julie Bishop that Australia would ‘soon be within range’ of a North Korean nuclear strike. That raises several crucial defence policy questions.

First, we need to ask: has Washington made it clear to North Korea’s dictator, Kim Jong-un, that an attack on America’s Australian ally will result in an overwhelming nuclear strike on North Korea? We have depended upon American extended nuclear deterrence ever since the ANZUS Treaty was signed in 1951. The North Korean regime should be left in no doubt that American nuclear strikes on that country would mean it ceased to exist as a functioning society.

Second, there’s the question of whether Australia should now take steps to protect itself from nuclear attack. The measures that could be considered include acquiring a ballistic missile defence capability and introducing prudent civil defence measures.

Ballistic missile defence was raised as a possibility in the 2009 Defence White Paper, including with reference to North Korea. The then Labor government’s policy was that it was opposed to the development of a unilateral national defence missile system because such a system ‘would be at odds with the maintenance of global nuclear deterrence.’

But, within that policy framework, the White Paper announced that Australia would explore the development of theatre capabilities for defence of ADF elements and other strategic interests—including our population centres and key infrastructure. It said the government would review its policy directions annually.

One option is for us to equip the Aegis air warfare destroyers, which are now being delivered to the RAN, with proven ballistic missile defence capabilities such as the SM-3 and SM-6. Another option is to go for the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) land-based system or future more advanced variants.

But as my colleague Stephan Frühling observes, the geometry is all wrong for such intercepts to occur close to Australia. By that time the re-entry vehicle containing the nuclear warhead is travelling at a speed of 6 to 7 kilometres per second or 21,000–25,000 kilometres an hour.

Ideally, we need to get much closer to the North Korean launch sites and attack their missiles when they’re in the vulnerable boost phase just as they are being launched.

The Turnbull government’s February 2016 Defence White Paper was entirely silent on this subject. Presumably, it recognised the difficulty—as well as the expense—of being able to devise a credible minimum ballistic missile defence capability at present. That shouldn’t prevent Defence from actively undertaking the necessary research and closely monitoring future technologies and their affordability.

There remains the question of why North Korea would bother targeting Australia at all when its main enemies are America, South Korea and Japan. There has been speculation that North Korea might choose Australia as a nuclear target to demonstrate its intent without threatening critical US targets in places such as South Korea and Japan, or bases such as Guam. That presumes the North Korean leadership would gamble that Washington wouldn’t retaliate by such a threat to its closest ally.

In fact, this isn’t the first time that Australia has been threatened in this way. On numerous occasions, the former Soviet Union threatened to target Pine Gap, Nurrungar and North-West Cape during a nuclear war. In 1980 former prime minister Malcolm Fraser directed the Office of National Assessments to produce a threat analysis. The resulting document, which has been declassified under the Freedom of Information Act, was classified Top Secret AUSTEO (for Australian eyes only) and only very few copies were made available to the most senior national security decision-makers

It argued that nuclear attacks on some or all of these facilities would probably occur in the event of nuclear war between the USSR and the US. It advised that any nuclear attack on North West Cape would probably kill the 2,000 residents of nearby Exmouth. And ‘assuming no unusual targeting errors’ the towns of Alice Springs and Woomera would not suffer major damage from heat, radiation or blast. But it admitted that the number of injured, ‘would be strongly dependent on civil defence measures’.

ONA wasn’t certain whether Soviet nuclear attacks on other Australian cities might occur, although it admitted that an attack on Canberra could render the federal government ineffective. Attacks on Sydney and Melbourne were a possibility. However, it claimed that, on balance, the Soviet Union would probably see Australian cities as low priority nuclear targets. That wasn’t my opinion at the time.

I was of the view that Fraser was remiss—given the advice he had been given by ONA—in not going ahead with even the most basic civil defence protection methods with regard to the joint facilities, not to mention major Australian cities. We face exactly the same quandary now with regard to North Korea.

International relations sometimes turn on points of deep uncertainty. One of the hottest current debates concerns the capabilities of the AN/TPY-2 radar associated with the THAAD system being deployed in South Korea. The question of how far the radar can see into China ranks up there with great mysteries, such as the fate of the crew of the Mary Celeste and the air-speed of an unladen swallow. The headline of a Reuters column captured the dilemma neatly: ‘China wary about US missile system because capabilities unknown’.

Estimates of the radar’s range vary widely—blurred in part by the fact that it can be used in two modes. In its forward-based mode, the radar is deployed in reasonable proximity to the probable launch point. It detects and tracks all classes of missiles in their launch/boost phase, and subsequently hands off its data to the wider Ballistic Missile Defence System. In its terminal mode, itmonitors incoming missiles and warheads to enable interception by its THAAD battery.

Many of the arguments about the radar in South Korea assume it’ll be used in its forward-based mode. Chinese commentators, in particular, are concerned about its ability to degrade the effectiveness of China’s strategic missile arsenal, either by providing more granular data on Chinese missile testing, or by contributing early trajectory data to the broader US Ballistic Missile Defense System. But in South Korea, the principal mission will be to guide terminal interceptions by THAAD. It’s primarily going to be used in the terminal mode. True, the hardware’s the same for both modes and swapping the software seems to take only a matter of hours.

Still, with the radar configured to its forward-based mode, the THAAD interceptors in South Korea would be largely useless. An AN/TPY-2 operating in forward-based mode can support cueing for another AN/TPY-2 operating in terminal mode, but it can’t replace it.

With that caveat, let’s have a closer look at range estimates. Back in September 2012, US scientists George Lewis and Theodore Postol calculated the radar’s range as 870 km for simple detection, and 580 km for discrimination. Lewis and Postol spell out in detail the assumptions upon which their calculation is based. One of those assumptions, for example, is that the target is ‘a conical warhead with a radar cross-section at X-band of 0.01m2.’

The Lewis and Postol estimate coincides broadly with the figure used later by Jaganath Sankaran and Bryan Fearey, who argue that ‘a THAAD radar would have a maximum range of approximately 800 kilometers under even highly optimistic conditions’. Sankaran and Fearey use that estimate to point out that the radar would have almost no capability to detect and track Chinese ICBMs.

In July 2016, a commentator on a missile defence blog separated out a range of different estimates—from about 480 km to 3,000 km—and explored the reasoning behind them. The range is shortest when the radar is in terminal guidance mode, and at its (uncertain) longest when in the forward-based mode. That makes sense. The range of the THAAD interceptor is about 200 km. There’s little point in having a radar with an excessively long range if its primary function is to guide interceptors to targets in the demanding terminal phase.

So let’s assume 800 km is approximately right for the radar in its forward-based mode. Yes, the range would be longer if the target were bigger—if the radar were looking at a warhead from side-on, for example, rather than front-on. And, yes, the radar will get better over time. It’s currently being upgraded from gallium-arsenide to gallium-nitride components: the benefits, apparently, include enhanced range, and increased detection and discrimination performance. The software’s getting better too.

But I think the Reuters headline is wrong on one important point: Chinese analysts are concerned about the radar not simply on the basis of what they don’t know, but on the basis of what they do. They only have to look at the record of testing by the US Missile Defense Agency (MDA) to know that the AN/TPY-2 radar, operating in its forward-based mode, is frequently a featured sensor, even in relation to intercepts of longer-range missiles. See, for example, this brief video of FTG-05, a test conducted in December 2008. The AN/TPY-2, deployed in Juneau, Alaska, acted as the forward radar in relation to the tracking and interception of a missile launched from Kodiak, Alaska.

Then there are tests for which little unclassified data is available. In relation to the ‘Fast Aim’ test in August 2013, for example, the US Director of Operational Testing and Evaluation wrote only: ‘In Fast Aim, the MDA demonstrated a capability of the AN/TPY-2 (FBM) radar to support a potential new BMD capability against ICBM threats’. Teasing, don’t you think?

So China does have a case that AN/TPY-2s in the forward-based mode can support the interception of ICBMs. The flaw in that case doesn’t really rest on the capabilities of the AN/TPY-2 radar, nor even on the fact that the South Korean radar will likely operate principally in terminal mode. It rests on China’s assumption that it’s entitled to a guaranteed second-strike nuclear capability. No such guarantee exists in international security. Yes, Mutual Assured Destruction was—and is—a key feature of the US-Russian nuclear relationship. But MAD evolved from technological facts; the facts did not evolve from it. Here, the facts are pulling in a different direction. It’s up to China—not the US—to ensure it has a second-strike capability.

Finding a solution to North Korea’s accelerating nuclear and missile programs grows more urgent by the day. Our previous strategies—delay and denial—will no longer avail us. But the three standard options—diplomacy, sanctions or use of force—all have downsides. Diplomacy’s proven ineffective; sanctions are difficult, slow and uneven; and the use of force might well beget a wider war. Is there a sleeper option—regime change? In the wake of Iraq and Libya, regime change has a bad name. But the question’s worth revisiting, precisely because of the recent killing of Kim Jong-nam.

Kim Jong-il died in December 2011. Now, over five years later, we’re starting to get a clearer picture of what the successor regime looks like. It’s a regime run by a leader who’s both ruthless and insecure. Consecutive waves of purges have cut a swathe through North Korea’s elite, claiming the scalps of Kim Jong-un’s uncle and senior military leaders among many others. Kim Jong-nam is the latest victim of that effort. Part of Kim Jong-un’s insecurity seems to stem from his own familial circumstances. The middle child (of three children) from his father’s fourth common law wife, he probably believes that some of his brothers and sisters still favour a different distribution of their father’s estate. Such a belief would be far from unusual even in most normal families, and the Kim family is far from normal.

Kim Jong-un and his wife had a daughter, named Kim Jun-ae, in 2012. We know this from Kim Jong-un’s close friend, Dennis Rodman. It’s possible—not certain, but possible—that a son was born to the couple in late 2016. Ri Sol-ju, Kim Jong-un’s wife, spent several months out of the public eye. Rumours at the time suggested either a possible pregnancy or a falling out of favour between the wife and Kim Jong-un’s younger sister, Kim Yo-jong. By late October 2016, Ri Sol-ju had been out of the limelight so long that the British tabloid press had begun to speculate on her execution. She reappeared in public in early December—certainly not clutching a new-born babe, but that’s hardly surprising. Pyongyang’s not Buckingham Palace—it doesn’t announce the birth of an heir with fanfare and photographs.

If an heir was born in 2016, it would have underlined for Kim Jong-un just what a difficult path now lies before him. It will take the best part of three decades for him to settle the leadership on his son. If he were to die unexpectedly at some point during that period—from ill-health, misadventure, or a drone through his bedroom window—it would be hard to ensure the succession played out as he wished. In such circumstances, the ‘side branches’ of the family could prove a threat, not merely to his own rule, but to the future rule of his son. Kim Jong-un probably doesn’t worry too much about the second brother—Kim Jong-chol, devoid of progeny, remains so thoroughly hidden from public view that many people seem to have forgotten about him altogether. Media reports suggest he’s more interested in rock concerts than politics. Kim Jong-nam was a different matter though—he still had close links to China. And even Kim Jong-nam’s son, Kim Han-sol, born in 1995, might well be regarded as a plausible contender for the future leadership.

Kim Jong-un probably counts the death of his half-brother as a major victory, important in securing the future transfer of the leadership. True, Kim Han-sol is still alive, but has clearly fled with his mother and sister. Kim Jong-un’s problem, though—and it surely must have occurred to him by now—is that his actions have strengthened his personal position but disempowered the broader family. A Kim family that has fewer potential successors—and the preferred one still thirty years away (assuming that he has, in fact, already been born)—is more vulnerable to the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune than it was before. Indeed, the prospects for successfully displacing the Kim family from its monopoly on political power in North Korea are probably greater now than they’ve ever been. In short, we’ve entered a period in which we have a stronger Kim, but a weaker family of Kims.

That’s what now confronts those hoping to slow and, indeed, reverse the growth of North Korea’s nuclear and missile arsenal. Kim Jong-un’s hand is stronger, but he’s shrunk the leadership talent pool within the family, thereby diluting the prospects that someone from that pool can follow in his wake. (North Korea, remember, has never been ruled by someone from outside the family.) And in doing so, he’s made himself a more tempting target: it’s always easier to behead the snake than the hydra. So, we’re left with a teasing question: have Kim Jong-un’s actions increased or decreased the prospects for regime change in Pyongyang?