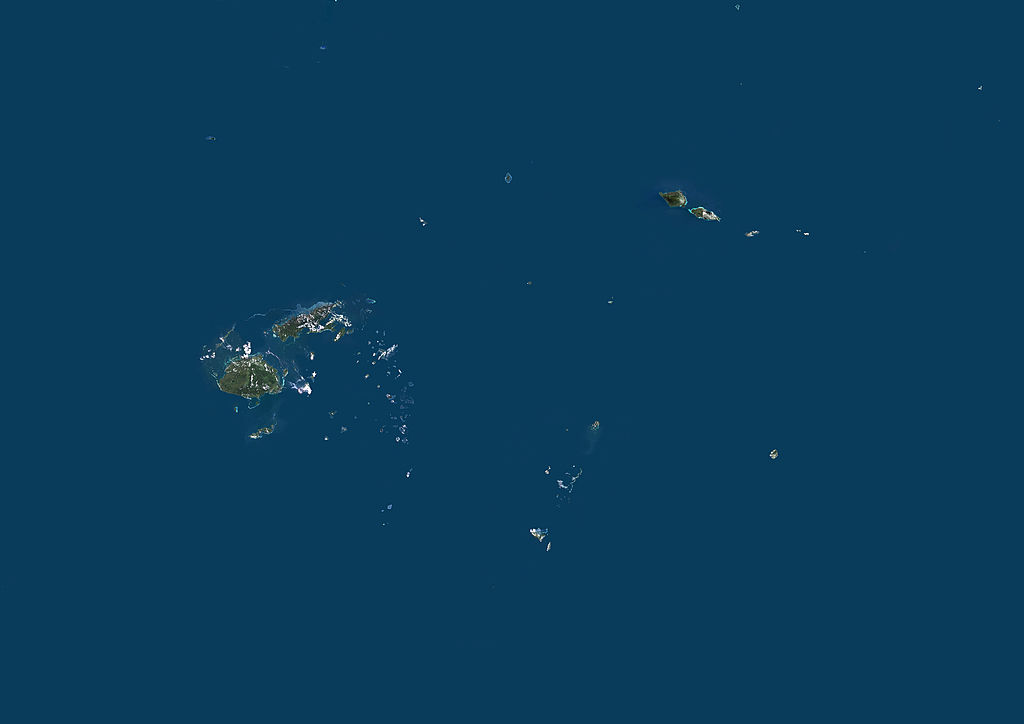

Australia and New Zealand can make Solomon Islands a ‘Pacific family’ offer China can’t match

The announcement by the Solomon Islands government that it intends to ‘broaden its security and development cooperation with more countries’ has provoked a rash of commentary from Australian and New Zealand journalists, academics, think-tankers and politicians. Amid the calls to ‘amass an amphibious invasion force’ or offer the Solomons an Australian naval base, is there potential for a ‘Pacific family’ solution?

The commentary erupted on 24 March after a leaked draft security agreement between Solomon Islands and China was circulated online. Controversial elements of the document include the following two provisions:

Solomon Islands may, according to its own needs, request China to send … armed police, military personnel and other law enforcement and armed forces to Solomon Islands to assist in maintaining social order …

China may, according to its own needs and with the consent of Solomon Islands, make ship visits to, carry out logistical replenishments in, and have stopover and transition in Solomon Islands, and the relevant forces of China can be used to protect the safety of Chinese personnel and major projects in Solomon Islands.

The agreement also features a confidentiality clause that says: ‘Without the consent of the other party, neither party shall disclose the cooperation information to a third party.’

While the deal has now been ‘initialed’ by Chinese and Solomon Islands officials, it is still yet to be formally signed.

Reflecting the possibility of secretive negotiations for a Chinese naval base in Solomon Islands, reactions from commentators covered the spectrum from ‘wake-up call’ to Australia’s own ‘Cuban missile crisis’.

Notwithstanding different positions along the alert–alarm spectrum, there’s broad agreement among commentators that Australia’s foreign policy approaches have proved inadequate, regardless of the funds spent on programs.

Meanwhile, a statement on Solomon Islands issued jointly by Australia’s foreign minister and minister for international development and the Pacific gave little indication of alarm, but within 417 words made five references to Australia’s ‘Pacific family’, with whom Australia stands ‘shoulder-to-shoulder … through good times and bad’.

The statement affirmed that Australia respects ‘the right of every Pacific country to make sovereign decisions’; referred to $22 million Australia has provided to the Solomons for budget support and record regional development assistance; and pledged that Australia would ‘be transparent and … continue supporting peace, economic prosperity, stability and democratic values across our region’.

A higher level of concern was articulated in an ABC article that quoted Solomon Islands opposition leader Matthew Wale saying he had warned Australian officials in late 2021 that ‘China would likely try to establish a military presence in Solomon Islands … but the Australian government did nothing about it’. The article also quoted Australian international affairs expert Clinton Fernandes warning that the same factors could well play out in Papua New Guinea.

Perhaps the big question is why the government of Manasseh Sogavare, on record for wanting to cooperate with China ‘to build a world that is fair and just’, was negotiating a security agreement with Beijing without first seeking the endorsement of the people of Solomon Islands? An APMI Partners survey carried out in the Solomons in December found that 91% of respondents preferred their nation ‘to be diplomatically aligned more towards … liberal democracies’.

Insight into this question may be provided by a case study by Indo-Pacific researcher Cleo Paskal titled ‘How China buys foreign politicians’. Paskal presents what appears to be evidence of August 2021 payments originating from China to ‘39 of the [Solomons] Parliament’s 50 MPs’. According to Pascal, all of these MPs were ‘supporters to one degree or another, of the Prime Minister’. Alluding to Article 61 of the Solomons constitution, Paskal notes that 39 votes would be sufficient ‘with a small buffer’ to pass an alteration and push through Sogavare’s plan to delay the 2023 election until 2024. ‘And who knows what else he and/or Beijing would like to “adjust”?’ she asks.

We get now to the heart of the problem. As Australia and New Zealand emphasise transparency, sovereignty and democratic values and spend big on multimillion-dollar development projects, the geopolitical landscape may be rearranged by a series of budget bribes to members of Pacific parliaments. For, as Fernandes suggests, there’s no reason to think this vulnerability will be restricted to the Solomons.

Many Pacific islanders have strong links with Australia and New Zealand through education and family dating back to pre-independence times. If the APMI survey data is anywhere near accurate, Solomon Islanders remain strongly drawn to the liberal democratic model. Should, therefore, the leading democracies of the region respond to the strategic competition from China by seeking to make the much-vaunted ‘Pacific family’ more of a reality?

In other words, what policy options might be offered to Solomons government MPs such that alliance with the leading liberal democracies of the region becomes a permanent policy setting? What could be so attractive to the entire Solomons electorate that going against it even for money politics would be unthinkable?

The answer may be something Australians and New Zealanders enjoy most days of their lives—namely, access to a developed job market, education and healthcare. Establishing a path for greater integration of the Solomons and other Pacific island states into a ‘Pacific family’ led by Australia and New Zealand, in return for a common security policy, could settle for good the partner-of-choice question for these states. At the same time, increased opportunities for Pacific workers could provide badly needed labour and help stimulate a regional industrial revival.

Steps towards greater integration of Pacific states would represent a substantial change for Australian and New Zealand foreign policy. However, the audacious geopolitical manoeuvre by China calls for an equally innovative response from the region’s leading liberal democracies.