If New Zealand wants to restate terms with Cook Islands, it should step up support

New Zealand wants to renegotiate its free association agreements with Cook Islands to secure increased transparency in its foreign partnerships. To do so, New Zealand will need to step up its own support and can learn a thing or two from Australia.

Following the announcement of an agreement between the island nation and China this week, New Zealand’s foreign affairs minister, Winston Peters, on Wednesday said his country and Cook Islands needed to ‘reset’ the relationship and ‘re-state the mutual responsibilities and obligations’. He stressed that consultation and transparency was most important.

His stance seems to raise the possibility that New Zealand will seek a power of veto over Cook Islands’ agreements with other countries.

But New Zealand must be careful not to overstep when Pacific sovereignty is at stake: every Pacific island nation is entitled to engage with foreign partners, including China. But Wellington also has a right to ensure that its support to Cook Islands is not jeopardised by engagement with other foreign partners.

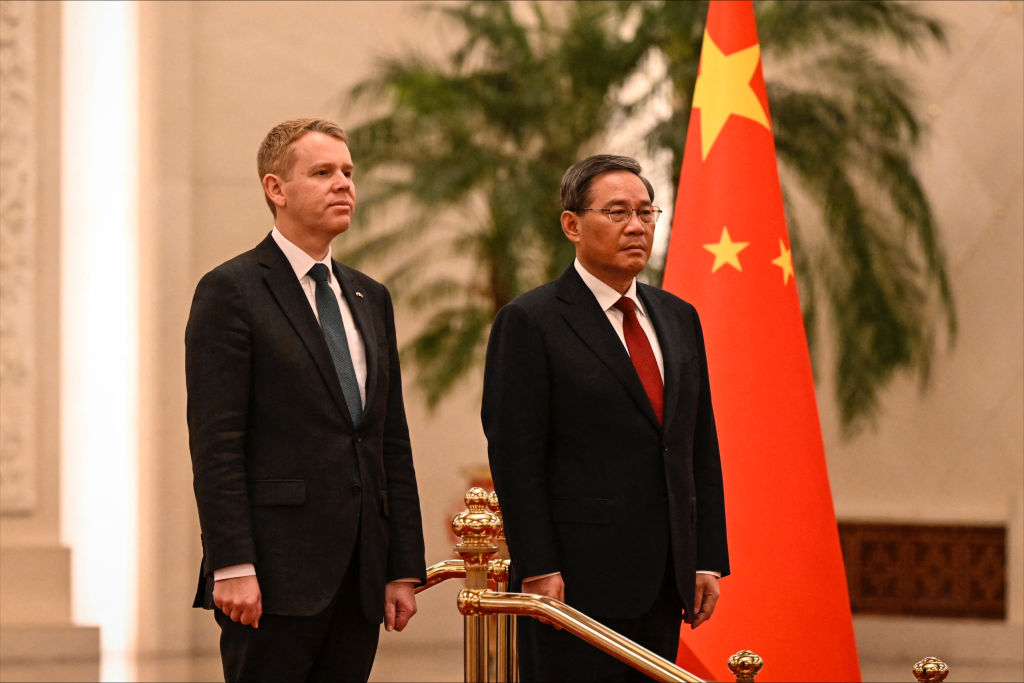

This week the Cook Islands government released an action plan for its comprehensive strategic partnership with China. New Zealand is uncomfortable with the Cook Islands government’s lack of consultation with Wellington before the agreement. The deal’s inclusion of cooperation around sea-bed mining, diplomatic missions, maritime cooperation and humanitarian aid must be putting New Zealand even more on edge.

The plan identifies priority areas including economic resilience, environment, cultural exchange, social well-being and regional and multilateral cooperation. It reiterates Cook Island’s commitment to its One-China policy.

Seabed mining, noted as a ‘national priority for the Cook Islands’, remains a key motivator for Cook Islands Prime Minister Mark Brown. The section on maritime cooperation also contains opportunities for cooperation on hydrography, geospatial and foreshore protection, maritime support and attendant infrastructure. This support could provide excuses for increased visits and engagement by Chinese security forces. Disaster management cooperation also strays into New Zealand’s defined role but will likely be limited by distance and emergency response times.

China already engages with Cook Islands at several regional-level forums on fisheries and foreign affairs. But the two countries now commit to bilateral ‘discussions’ before any regional meetings hosted by Cook Islands that China is to attend. China has also been supporting Cook Islands infrastructure development for years, building a court house, police headquarters, sports stadium, school and water supply network. However, not all support has earned favour, with some projects requiring substantial repairs after China’s substandard work.

The action plan notably lacks the security strings that much of the world was worried about. Although Brown promised no security deals, Wellington may still fear the slow-growing Chinese presence and influence that may accompany activities in the plan.

Brown now faces domestic upset. There was a popular protest of over 400 people in the capital (more than one in 40 people in the nation). Opposition party members have filed a motion of no confidence. They are frustrated that the deal is jeopardising the partnership with New Zealand.

In free association with New Zealand, Cook Islands is self-governing, but New Zealand assists in defence, disaster relief and foreign affairs. The 2001 Joint Centenary Declaration is a non-binding agreement to consult with New Zealand on national security issues, but Pacific security has changed dramatically in the past 20 years.

This is where New Zealand can learn from Australia’s new approach.

Over the past two years Australia has redefined competition in the region. Agreements with Nauru, Tuvalu and Papua New Guinea have given Canberra some degree of power to prevent other foreign countries from entering the same security or infrastructure space.

But it hasn’t come cheap.

In Nauru, Australia will provide $100 million in budget support over five years and ensure physical banking services in the country. Under the Nauru-Australia treaty, both countries must agree to any foreign engagement in Nauru’s security, banking and telecommunications sectors and consult on any engagement in critical infrastructure.

Similarly, in Tuvalu, the Falepili Union treaty states, ‘Tuvalu will mutually agree with Australia any partnership, arrangement or engagement with any other State or entity on security and defence-related matters’. In exchange, Australia is helping address Tuvalu’s climate threats and offering a special visa pathway.

Australia and PNG have just announced plans to restart negotiations on a treaty-level agreement. This follows Australia’s investment in a future PNG National Rugby League team.

In these agreements, Australia has highlighted the lasting value it will provide and has made it clear that foreign competition in the same space will prevent Australian support from reaching its potential.

If New Zealand doesn’t want Cook Islands engaging with China in certain sectors, including those outside traditional security, it will need to show commitment to developing those areas and delivering what Cook Islands needs. It can start by investing more in maritime security and infrastructure and addressing climate threats.

Stepping up in Cook Islands won’t solve all of New Zealand’s issues in the Pacific, with tensions still high in Kiribati and other leaders looking on cautiously. But they can at least start with taking care of their realm.