Why attack missile boats can’t replace major warships

Attack missile boats are no substitutes for the Royal Australian Navy’s major warships, contrary to the contention of a 4 February 2025 Strategist article. The ships are much more survivable than attack boats and can perform long-range operations that small vessels cannot.

In the article, the author argues, for example, that a single missile hit could cripple a billion-dollar warship. In fact, this is highly unlikely.

The planning for the number, type and direction of travel of missiles needed to successfully engage a warship is a tactical art. The calculations are classified, but the Salvo Equation is an unclassified means of understanding how many missiles must be fired to damage a major warship, such as a destroyer or frigate. The number is greater than most people assume.

The debate on warship survivability isn’t new, and it remains paper-thin. Warships are designed to float, move and fight. As the RAN’s Sea Power Centre describes, they are survivable ‘through layered defence systems, signature management, structural robustness and system redundancy’.

Just because a missile is fired doesn’t mean it will strike, and even a strike doesn’t ensure the ship is disabled.

It’s true that threats to warships close to coasts have increased, and the proliferation of uncrewed aerial vehicle, uncrewed surface vessels and anti-ship missiles has made operations more complex. However, as offensive threats evolve, so do defensive capabilities, tactics and procedures. This is the dance of naval warfare.

To bolster the flawed claim that warships are ‘increasingly vulnerable in modern conflicts’, the article points to the 42-year-old, poorly maintained Russian cruiser Moskva, which Ukraine sank in the Black Sea in 2022, as a ‘most advanced warship’. Yet far more modern US, British and French warships have repelled more than 400 Houthi missile attacks in the Red Sea since 2023 without sustaining damage. Fourteen months of Red Sea operations show that well-armed warships with trained crews are highly effective.

The article conflates strategy with concepts, saying ‘the urgency of shifting Australia’s naval strategy to distributed lethality cannot be overstated’.

Think of a naval strategy as the big-picture plan for what a nation aims to achieve at sea with its naval capability (as opposed to maritime), while a naval concept is the theoretical framework that explains how its navy might actually fight and operate to achieve those goals.

‘Distributed lethality’ fits within the established concept of Distributed Maritime Operations, which isn’t about any particular category of vessel, large or small; it’s a way of fighting that emphasises massed effects through robust, networked communications that allow for dispersal of maritime units.

At its core, it’s a network-centric, not platform-centric, concept—as applicable to a fleet of frigates and destroyers as to smaller craft.

It’s a concept the RAN, at least in theory, has already embraced. In a 2024 speech on Distributed Maritime Operations, Fleet Commander Rear Admiral Chris Smith said ‘distribution as a core concept of our operations … seeks to manage a defensive problem while seizing an offensive opportunity’.

Australian naval strategy: reach and balance

In advocating for a shift towards attack boats, the article dismisses their limited range and endurance as problems that are easily fixed. They are not: range and endurance are fundamental to Australia’s naval strategy and central to the concept of reach.

At its core, reach is the requirement for a maritime power to be able to protect its vital interests at range from its territory. As an island nation dependent on long sea lines of communication for essential seaborne supply—from fuel to fertiliser, ammunition and pharmaceuticals—Australia needs an ability to protect critical imports and exports.

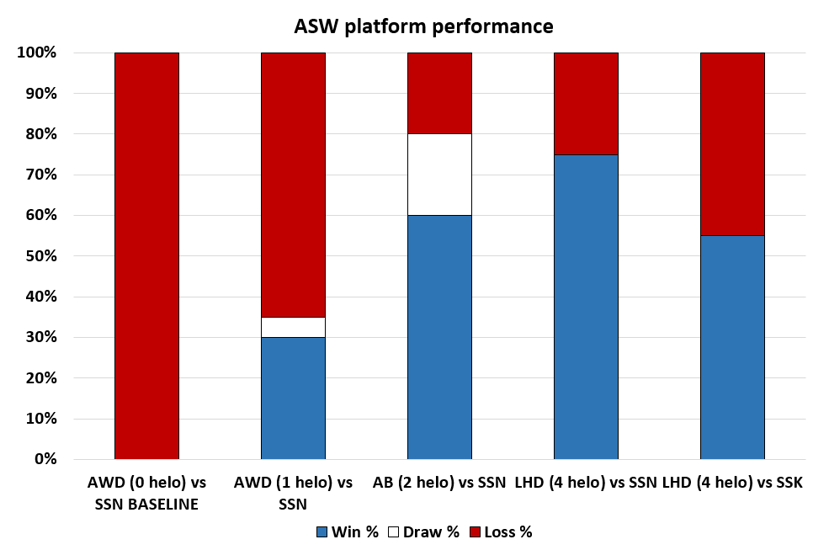

Doing that requires the combination of sensors and weapons that cannot fit into an attack boat: heavy and bulky towed-array sonars, large radars mounted high, long-range air-and-missile defence systems, and helicopters for hunting submarines.

Acceptance that Australia’s vital interests at sea are far from its coast is inherent in the roles ascribed in Australia’s National Defence Strategy. They include power projection, such as the capabilities of the Australian Army’s new amphibious fleet, which require protection that attack boats can’t provide.

Limited endurance and operational range are deficiencies that cannot be mitigated by basing in northern Australia, as the article suggests. Territorial force posture such as northern operating bases cannot transform coastal green-water naval assets such as attack boats into the open ocean blue-water capability Australia requires.

Another key strategic requirement for Australia is having a balanced fleet, anchored by larger destroyers and frigates. The essence of the idea of a balanced fleet is that a smaller fleet of ships must operate across the spectrum of maritime tasks. Attack boats cannot fight effectively in all three spheres of maritime warfare: surface, air and sub-surface. While they may complement frigates and destroyers where the budget allows, they are unsuitable to form the backbone of Australia’s fleet.

The call for such vessels falls into the common trap of thinking that modern naval warfare is simply about missile capability. But what is needed to constitute a balanced fleet is a mix of capabilities that can be brought together only in a frigate or larger ship.

This debate is an opportunity to highlight a crucial issue often overlooked in Australian strategic thought. The country needs a naval strategy with genuine reach and a balanced fleet, capabilities that simply can’t be met by a force built around attack boats.