The global fallout from war in Ukraine

How Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will play out remains unclear. But it’s already been a geopolitical game-changer—in Europe and beyond.

Russia’s aggression has jolted Europe out of its post–Cold War complacency. Lulled by decades of peace and confronted now by the reality of war next door, European states have been forced to take security more seriously and act to upgrade their defence capabilities. The sea-change is most striking in Germany, which has committed to a US$112 billion boost in defence spending and pledged to meet NATO’s 2% of GDP target. Norway, Italy, Austria, Denmark and Poland are among others committing to increased defence expenditure.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has reinvigorated NATO with a renewed sense of purpose and unity. The bloc is expanding its forward military deployments to reassure its eastern-most member states. Long-time Nordic neutrals Finland and Sweden are now contemplating NATO membership.

While underscoring the enduring importance of transatlantic security ties, the Ukraine conflict has spurred efforts to enhance the EU’s strategic autonomy, and security capabilities, outlined in the newly-approved ‘Strategic Compass’.

Although for now Washington must deal once more with the reality of security challenges in both Europe and Asia, increased European military capabilities may over time reduce the defence burden on the US, facilitating its pivot to Asia.

Yet the challenge ahead is to sustain European resolve and unity as the conflict in Ukraine drags on, especially as the economic costs of confronting Russia grow. Corralling those European states disposed politically to take a softer line on Russia, notably Hungary, will be difficult.

The Ukraine crisis has also prompted European governments, especially in Germany, to accelerate moves away from dependence on Russian gas. Short term, this includes diversifying sources of LNG, but it has also given impetus to the shift towards adoption of renewables. Nuclear power is enjoying a revival, especially in France, but also in the UK.

Beyond Europe, estrangement with the West has made closer relations with China a strategic necessity for Russia.

The partnership between China and Russia is based on shared authoritarian political affinities, economic complementarities, foreign policy convergences—especially, hostility to US primacy—and reassurance that each has the other’s back politically.

Yet despite talk of their strategic partnership knowing ‘no limits’, the relationship remains wary, transactional—and increasingly asymmetric, in Beijing’s favour.

On Ukraine, China has tilted towards Moscow—but its support has limits. Beijing won’t want to jeopardise its more important economic interests with the US and Europe (China’s US$147 billion trade with Russia is dwarfed by its US$1.4 trillion combined trade turnover with the US and EU). It is also aware of the reputational risks that support for Russia implies.

Beijing wants Russian President Vladimir Putin to survive—but not necessarily thrive. A humiliating defeat for Russia and a stronger and more united NATO under US leadership would not serve China’s interests. Yet a weakened Russia would be a more dependent and pliant partner for Beijing.

India’s relatively neutral stance on the Ukraine conflict has gratified Moscow but frustrated the West.

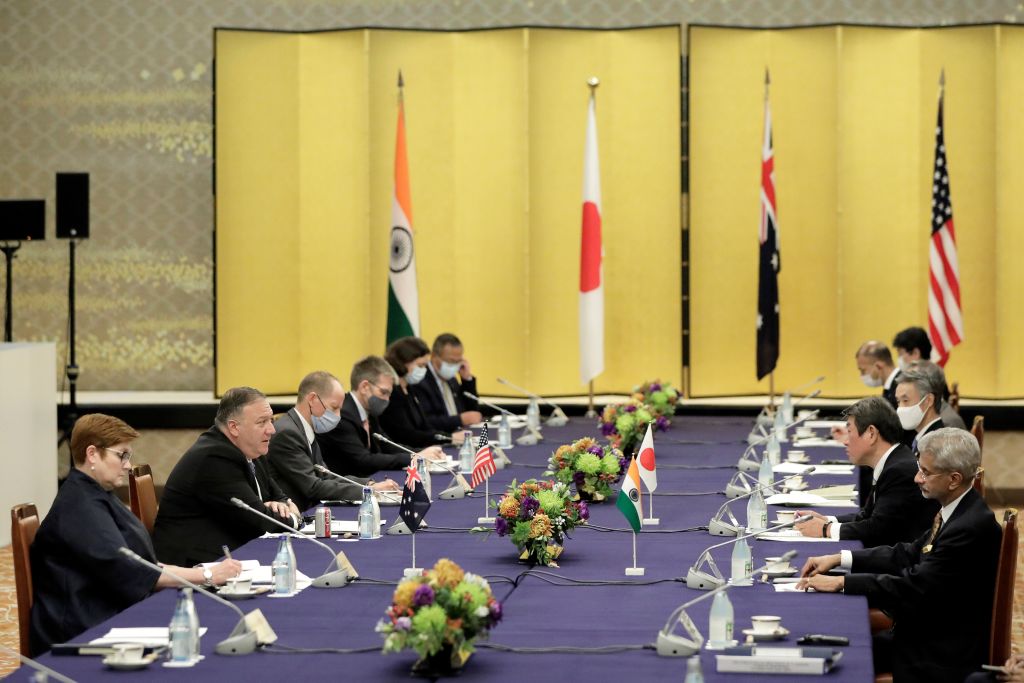

Yet India faces a dilemma. Moscow is a longstanding, friendly strategic partner. Trade, energy and, especially, military ties are strong (Russia remains India’s biggest weapons supplier). New Delhi is suspicious of Pakistan’s warming ties with Russia, and doesn’t want to drive Moscow into Beijing’s arms. Yet India’s relations with the US have expanded greatly, and New Delhi sees the Quad as a useful counter to China.

India, then, is walking a tightrope on Ukraine, trying not to antagonise either Russia or Western countries.

It is not alone.

While the result of the UN General Assembly vote condemning Russia’s aggression in Ukraine seemed impressive, this masked the reality that key developing countries, such as Indonesia, Brazil and South Africa, are essentially sitting on the fence. And nearly half the UN’s African members did not support the resolution.

For some developing states, this muted response reflects close ties to Russia—whether political, military or economic. Others are reluctant to be drawn into what is seen as a West versus Russia dispute, echoing the Cold War. And some are sceptical of the West’s motives, seeing double standards.

Russia’s actions in Ukraine pose a real challenge to the United Nations. When a veto-wielding permanent member of the UN Security Council commits unprovoked aggression against its neighbour, contravening those very principles of national sovereignty and territorial integrity the Security Council is charged with upholding, the UN is rendered powerless to act and, through its paralysis, loses credibility.

This has real, and worrying, implications, especially for small and mid-sized countries reliant on UN rules and institutions to underpin their security and prosperity. Some will conclude that they need to build up their own military capabilities—potentially sparking regional arms races.

And Russia’s growing pariah status brings its own problems.

The West’s strong response, providing political and military support for Ukraine and imposing damaging sanctions on Russia, will ineluctably reinforce anti-Western hostility in the Kremlin. This will make Russia even more difficult to deal with internationally. Don’t expect, then, Russian cooperation on issues like climate change, arms control and Antarctica. And Moscow may become a more disruptive force in unstable regions, such as the Sahel, Balkans and Middle East.

There are economic ramifications too.

Short-term energy and commodity prices have spiked. This has squeezed food supplies in Africa and the Middle East, both highly dependent on Russian and Ukrainian wheat—which carries domestic political implications. Already disrupted global supply chains have been further aggravated. Inflation has been fuelled worldwide, complicating recovery from the pandemic.

In the longer term, the Ukraine crisis will only further encourage the global drift towards political confrontation and economic nationalism, weakening globalisation and free trade. Efforts by Western states in particular to reduce their reliance on Russian energy, fertiliser, minerals and commodities will impose cost and efficiency burdens.

The Ukraine war is thus likely to exacerbate worrying political tensions and economic pressures, already aroused by the Covid-19 pandemic, intensifying US–China competition and the global energy transition.