A Biden return to Obama’s cautious China policies would be a big mistake

When Joe Biden made his first speech as president-elect of the United States, he declared that a revived America would ‘lead not by the example of our power, but by the power of our example’. For Americans who believed Donald Trump’s antics debased the office of the president, Biden’s pledge to restore Washington’s moral leadership would have offered much relief by evoking comfortable images of American exceptionalism. But those very images of a moralistic and restrained United States, while welcome domestically and perhaps in Europe, won’t help an Indo-Pacific grappling with the challenges posed by an increasingly aggressive People’s Republic of China.

The Indo-Pacific is a politically diverse, multipolar region whose constituent governments, by and large, want to retain their sovereignty and avoid falling under Beijing’s orbit. That requires an interested, engaged America that can act as a backstop against China’s military expansionism.

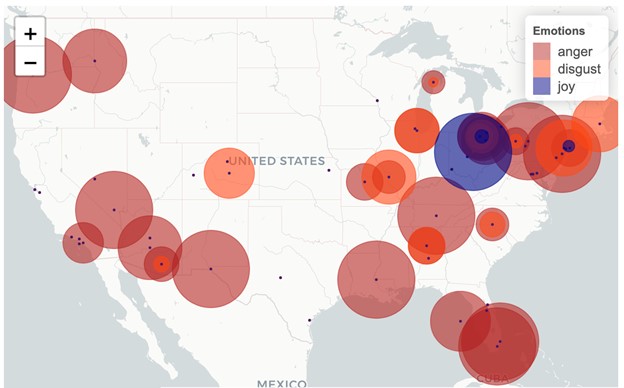

Though Trump’s personal bombast and antipathy for alliances rubbed some world leaders up the wrong way, his administration’s willingness to use American power sent an important message. Bilahari Kausikan, former permanent secretary of the Singaporean ministry of foreign affairs, outlined the case in a recent article for Nikkei Asia. ‘Trump understood power, albeit instinctively’, Kausikan observed. Whereas Barack Obama failed to enforce his ‘red line’ over Bashar al-Assad’s grotesque use of chemical weapons against his own people, Trump ‘bombed Syria … while at dinner with Xi Jinping’. The episode ‘did much to restore the credibility of American power’, Kausikan argued, for the simple reason that Trump had shown Beijing, rather conspicuously, that Washington’s red lines again meant something. That message likely offered some reassurance to a region facing China’s grey-zone coercion in the South China Sea.

To be fair, Biden hasn’t yet been given an opportunity to back up his rhetoric with demonstrations of American power. And the Biden campaign’s rhetoric has been appropriately tough. Jeffrey Prescott and Ely Ratner, two key advisers on the Biden campaign, argue that he ‘will rally the free world and mobilize half the world’s economy to hold Beijing to account for its trade abuses’.

Michèle Flournoy, who’s likely to be Biden’s defence secretary, believes that the US military will need reinvigoration so that it can ‘sink all of China’s military vessels, submarines, and merchant ships in the South China Sea within 72 hours’. Biden himself has even called Xi a ‘thug’. These are promising rhetorical signs that a Biden administration won’t be as reluctant as Obama’s to counter Chinese aggression.

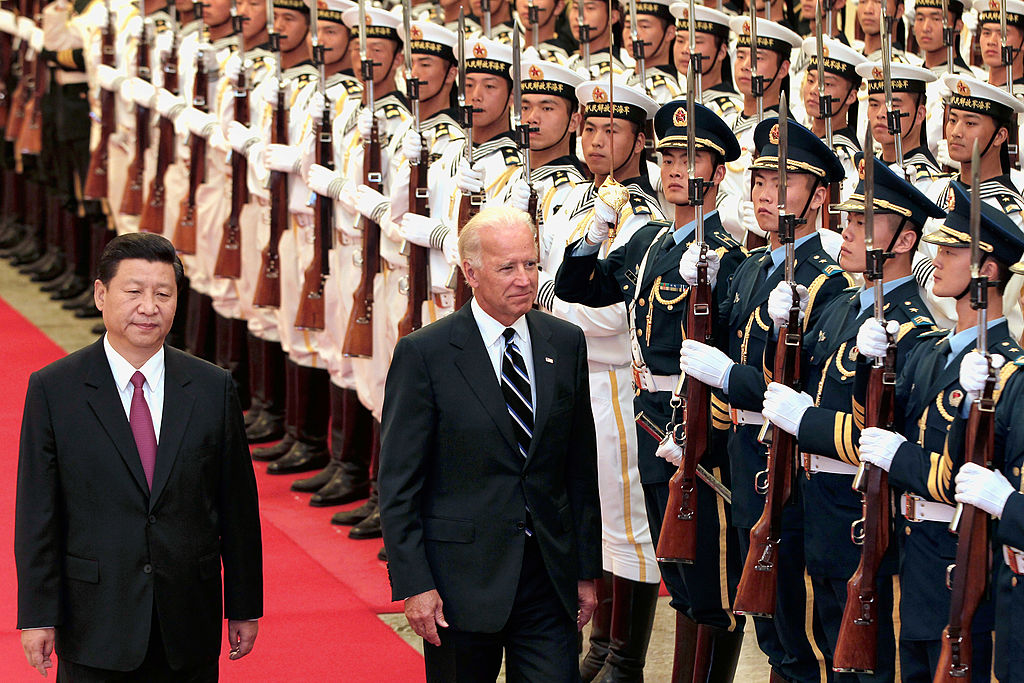

That said, the actions of the Biden team since the election suggest that the new administration may not walk the talk. The first sign was Biden’s apparent unwillingness to follow the Trump administration’s precedent by accepting a congratulatory phone call from Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-wen. Taiwan’s foreign minister, Joseph Wu, explained that Taipei had been working with Biden’s team on ways to ensure that Tsai’s congratulations were formally passed on to the president-elect. The result was a phone call between Taipei’s Washington envoy Bi-khim Hsiao and Biden foreign policy adviser (and the man who’ll reportedly be secretary of state) Antony Blinken, effectively downgrading US–Taiwan ties.

Rhetoric and phone calls aside, more insight into how Biden might approach China is likely to come from his picks for senior foreign policy roles. As Thomas Wright argued in an article for the Lowy Institute, the foreign policy advisers who will likely take key positions in a Biden administration can be divided into two camps: the ‘restorationists’ and the ‘reformers’.

‘Restorationists’ admire the judiciousness with which Obama deployed military force, assign similar weight to transnational threats and geopolitical competition in the conduct of American statecraft, and believe in America’s resilience as a great power. ‘Reformers’ believe that America needs to play a more active role in protecting its economic interests and cooperating with other countries, particularly democracies, to out-compete rising powers like China.

The most notable restorationist is Susan Rice, who was in the running to be Biden’s secretary of state but did not get the nod. This will be welcome news to Asia hands. Numerous commentators have argued that Rice’s appointment to any senior role would be poorly received across the Indo-Pacific, especially in Japan, due to her reportedly weak grasp of regional issues.

Another restorationist is John Kerry, who has just been selected as Biden’s presidential envoy for climate change. Given China’s status as the world’s largest polluter, Kerry’s job will be to find ways of working with Beijing in order to secure a meaningful multilateral deal on climate change. Whether Kerry’s bid to cooperate with Beijing will come at the cost of some of Biden’s more competitive policies will depend on how effective other members of Biden’s team are at getting the president’s ear.

That’s where the reformers come in. Kurt Campbell is probably the best-known reformist in the Biden camp, having been the architect of Obama’s ‘pivot to Asia’ strategy. Campbell has long argued that the US needs to develop a coherent strategy to out-compete China militarily, diplomatically and economically. Campbell’s views, along with his considerable expertise and connections in the region, would make him welcome in most Indo-Pacific capitals. However, his name, hasn’t arisen much in press speculation about Biden’s possible senior appointments. Even if other reformers, like Ely Ratner and Jeffrey Prescott, take reasonably important roles in the national security bureaucracy, it seems unclear just how much influence the group will have with the president.

Sitting between the restorationists and reformers is Antony Blinken, who has been announced as Biden’s pick for secretary of state. Blinken seems to have developed a stronger appetite for competition than other Obama-era figures, but wants to work with Beijing to ensure that these competitive dynamics don’t escalate into confrontation. The task for Blinken will be to strike the right balance and ensure that the Biden administration doesn’t revert to the old norm of US diplomacy that privileges cooperation with China over competition.

Important though foreign policy cliques may be, domestic challenges are likely to take up considerable bandwidth in the Biden White House. In this respect, the writings and ambitions of Jake Sullivan, Biden’s pick for national security adviser, are particularly revealing. A former foreign policy hand in the Obama administration, Sullivan has been vocal in arguing that American foreign policy needs to better address the country’s internal needs, and he was reportedly more interested in a domestic policy role during the campaign. Given the weight of America’s problems at home, ranging from the coronavirus to a burgeoning national debt, it seems likely that Sullivan will ensure Biden’s key foreign policy decisions are better aligned with America’s domestic priorities.

Joe Biden may prove to be a president who takes a tough-minded approach to China that is supported by a well-executed and competitive strategy. Yet, what emerges from a preliminary look at the Biden transition is an administration that looks similar to Barack Obama’s—risk-averse and preoccupied by domestic concerns. For Americans who want to see a divided (and sick) nation heal, that may be just what the doctor ordered. But for countries in the Indo-Pacific that are living under the shadow of an increasingly aggressive Beijing, reviving the Obama administration’s overly cautious approach would be a bad outcome.

America can’t just lead by the power of its example. It also needs to lead by the example of its power.