Ending the forever war in Afghanistan

Speaking in Kabul on 14 February on the 32nd anniversary of the Soviet Union’s withdrawal from Afghanistan, the country’s president, Ashraf Ghani, made an important distinction. The civil war that devastated Afghanistan after the withdrawal was caused not by the departure of Soviet troops, but by the failure to formulate a viable plan for Afghanistan’s future. As the United States considers its own exit from the country, it should heed that lesson.

After withdrawing its troops in 1989, the Soviet Union continued to provide financial support to the communist-nationalist regime, led by President Mohammad Najibullah. But, lacking domestic legitimacy, Najibullah’s regime quickly collapsed when Russia withdrew its financial support in 1992, triggering the civil war. Then, in 1996, the Taliban gained control of Kabul and, ultimately, the country.

The Taliban remained in power until 2001, when a US-led invasion—spurred by the 9/11 terrorist attacks—ended its rule. But last February, US President Donald Trump’s administration reached a deal with the Taliban intended to end the nearly 20-year-long war: the US and its NATO allies would withdraw all troops by May 2021 if the Taliban fulfilled certain commitments, including cutting ties with terrorist groups and reducing violence.

The Taliban would also have to engage in meaningful negotiations with the Afghan government, which was not involved in the deal. The Trump administration apparently hoped that an intra-Afghan peace agreement would materialise by the designated withdrawal date, ending the fighting and minimising the risk that Afghanistan would become a haven for terrorists.

That hasn’t happened. While US force levels are down to around 2,000 troops, fighting in Afghanistan hasn’t decreased. On the contrary, a US watchdog agency reports that the Taliban carried out more attacks in the last quarter of 2020 than during the same period in 2019. Moreover, the latest intra-Afghan talks, which began in Doha in September, have produced virtually no results.

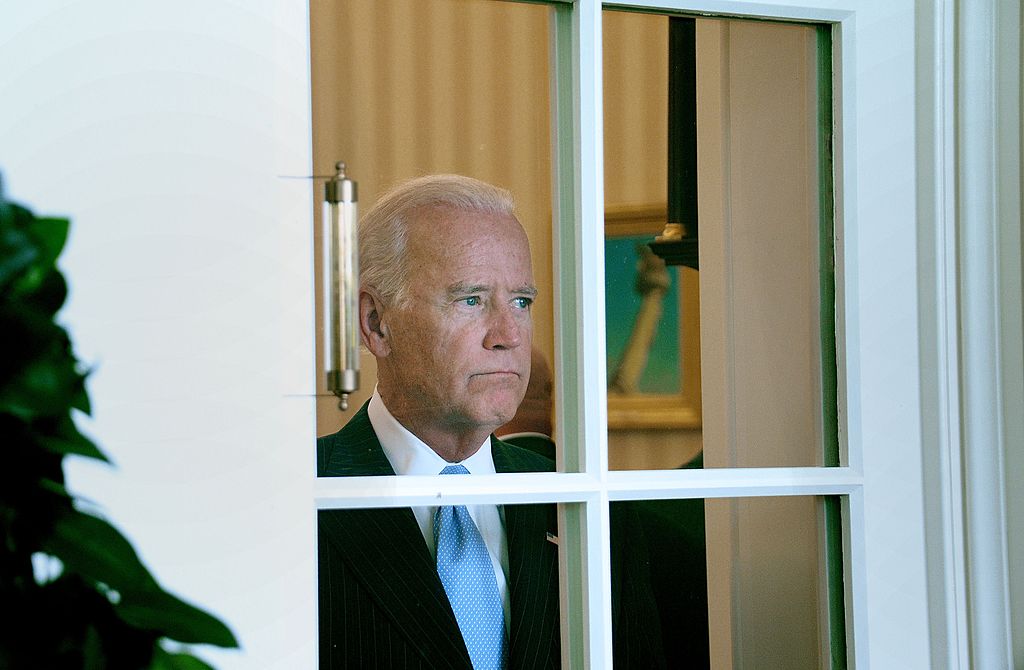

It seems that the Taliban’s plan was to keep fighting until US troops left, at which point they might be able to secure a victory in the long war. Now, however, they face the possibility that US troops won’t leave nearly as soon as expected. President Joe Biden’s administration has announced that it is reviewing the deal to determine whether the Taliban is ‘living up to its commitments’.

The Biden administration must also decide what to do about America’s NATO allies, which together have substantially more forces in Afghanistan than the US does. And—as the post-Soviet experience indicates—it must devise a plan for influencing the situation in the country and region after the withdrawal.

The challenge is formidable. Afghanistan is one of the world’s poorest countries. Today, the Afghan state’s income amounts to little more than a third of what the US pays only to sustain its various security forces, to say nothing of US aid to the civilian sector (which, to be sure, amounts to less than half Europe’s contributions). In fact, Afghanistan has depended on outside support to sustain its statehood since Russia and Britain played their ‘Great Game’ in the 19th century.

As it stands, the US seems to be leaning towards maintaining some sort of security presence, focused on fighting the terrorists of al-Qaeda and the Islamic State, beyond the May deadline. German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas has advocated this approach.

But there are risks. The Taliban could reject this solution, leading to an intensification of fighting and renewed attacks on international forces. Zalmay Khalilzad, the US special representative for Afghanistan reconciliation, is most likely already working to assess this risk.

The Taliban’s acceptance of a continued security presence may depend on progress in the intra-Afghan talks, though no one seems to have a clear vision for a power-sharing agreement. The gap between today’s Islamic Republic and the Taliban’s desired Islamic Emirate is wide, and narrowing it will require a recalibration of the diplomatic process concerning Afghanistan.

To that end, regional powers—including Iran, Russia and China—should be engaged in all talks about the country’s future, with one or two also taking a more active role in facilitating the intra-Afghan political dialogue. In this process, managing the dynamics between India and Pakistan, for which developments in Afghanistan hold profound national security implications, will undoubtedly emerge as a key challenge. Indeed, at the moment Russia is taking the initiative in this regard.

The pressure in the US and elsewhere to end the ‘forever war’ in Afghanistan is understandable. But, as Ghani wisely warned, simply withdrawing international forces is unlikely to yield that result. To avoid a new spiral of violence, we must first determine what will come after.