ASPI suggests

Welcome back.

Last week it was Ivanka as seat warmer, and this week it was Donald Jr’s time to shine. (Sasha and Malia never got this much attention …) We now know that there was direct and unalloyed collusion between Trump’s inner circle and the Russian government. Oy vey. So here are a couple of reads. First, a piece in The National Review explores the ‘misconduct of public men’, raising some tough questions about the president’s truthfulness and his fitness for office. Ross Douthat, resident conservative over at The New York Times, is walking back from his earlier position of giving Trump the benefit of the doubt. The fantastic CSIS-TCU podcast series continued this week with Vox founder Ezra Klein. And over at his site, Klein is running with Elizabeth Drew’s characterisation of the Watergate years: ‘a time of low comedy and high fear’.

Last week I highlighted some career opportunities for the young(er) guns; this week it’s all about self-improvement for the young scholar. This effort over at War on the Rocks reckons the key is to devour the world beyond your discipline: hoist it all in together and try to make sense of what’s going on. And from the kind folks over at The Strategy Bridge, here are some thoughts and tools to train the strategic-thinking muscle.

As the dust settles on North Korea’s ICBM launch last week, don’t miss this stand-out interview with Jeffrey Lewis (he of Arms Control Wonk fame). And in case you missed it last week, the latest edition of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists—the bunch with the clock—dropped with phenomenal timing.

Astrophotography is pretty sweet any day of the week, so things naturally just get better when you add some kit and platforms into the mix, right? Yup, exactly. US soldier Joshua Simmons has made use of things laying around at his Fort Hood base to bring the military together with the Milky Way. Nicely done. For more on the photography front, don’t miss this recent account of the work of Aussie talent Andrew Quilty, who has been based in Afghanistan since 2013. His photojournal, 28 days in Afghanistan, is also worth the time.

And to add some levity to the week’s end, how’s this for a yarn: Jim Mattis’ mobile phone number is revealed online and a high-school student calls and texts in an effort to score an interview. A week later, Mattis calls back for what turned into a 45-minute chat about US foreign policy. The episode sparked two pieces: one feature and one reflection. You can also take a squiz at the transcript.

Podcasts

If you resisted my earlier calls to dive into Malcolm Gladwell’s 2016 postcast Revisionist History then I’m back to wear you down some more … Gladwell has been back on the beat to work up a second season, with five episodes out so far. One that’s likely to be of particular interest to Strategist readers tells the tale of a CIA asset, an Islamic militant who had a change of heart only to end up as a casualty of Bill Clinton’s efforts to reform the agency. But they’re all solid, so take a look here (39 mins). Much of the series hinges on behavioural science, so Gladwell’s interview with Dave Nussbaum, a behavioural scientist, is rather revealing.

A few weeks back the ANU hosted an event for the launch of Nick Bisley’s Center of Gravity paper, Integrated Asia: Australia’s Dangerous New Strategic Geography. If you couldn’t get along, never fear, as La Trobe Asia thought to record Nick’s chat with the SDSC’s Andrew Carr. Catch up here.

Video

If you find the whole concept of cryptocurrency to be entirely foreign and bewildering—Bitcoin, Ethereum, how–what–why—here’s your chance to get up to speed. It’s a technical topic, so there’s a limit to how close to the ground any explanation will stay, but absorbing this video will stand you in good stead (26 mins).

Events

Perth: Those on the west coast should get along to the PerthUSAsia Centre’s event on 20 July, Indonesia to 2050: A New Era for Australia–Indonesia Relations. Marty Natalegawa, Mari Pangestu and John Blaxland will all be there. Details here.

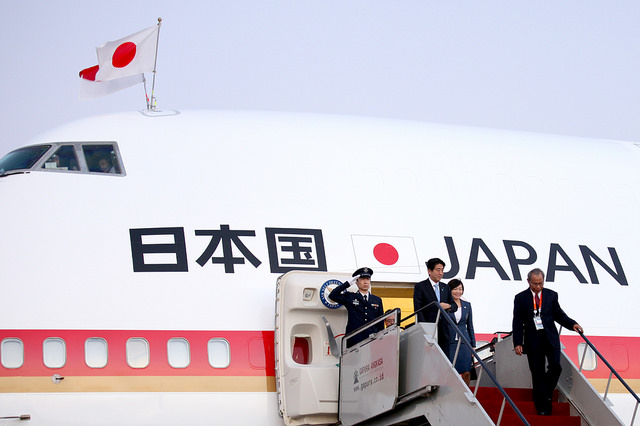

Canberra: No plans on Monday night? Just as well, because the Asia Bookroom—a Canberra gem—will host the launch of a significant new tome on Japanese war criminals written by four academics from Australian universities. The gang of four will be in conversation, with their effort to be launched by Michael Wesley. Register over at the Asia Bookroom website.