Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

How Joe Biden handles China will be one of the defining issues of his presidency. He inherits a Sino-American relationship that is at its lowest point in 50 years. Some people blame this on his predecessor, Donald Trump. But Trump merits blame for pouring fuel on a fire. It was China’s leaders who lit and kindled the flames.

Over the past decade, Chinese leaders abandoned Deng Xiaoping’s moderate policy of ‘hide your strength, bide your time’. They became more assertive in many ways: building and militarising artificial islands in the South China Sea, intruding into waters near Japan and Taiwan, launching incursions into India along the countries’ Himalayan border, and coercing Australia economically when it dared to criticise China.

On trade, China tilted the playing field by subsidising state-owned enterprises and forcing foreign companies to transfer intellectual property to Chinese partners. Trump responded clumsily with tariffs on allies as well as on China, but he had strong bipartisan support when he excluded companies like Huawei, whose plans to build 5G networks posed a security threat.

At the same time, however, the United States and China remain interdependent, both economically and on ecological issues that transcend the bilateral relationship. The US cannot decouple its economy completely from China without enormous costs.

During the Cold War, the US and the Soviet Union had almost no economic or other interdependence. In contrast, US–China trade amounts to some US$500 billion annually, and the two sides engage in extensive exchanges of students and visitors. Even more important, China has learned to harness the power of markets to authoritarian control in ways the Soviets never mastered, and China is a trading partner to more countries than the US is.

Given China’s population size and rapid economic growth, some pessimists believe that shaping Chinese behaviour is impossible. But that isn’t true if one thinks in terms of alliances. The combined wealth of the developed democracies—the US, Japan and Europe—far exceeds that of China. This reinforces the importance of the Japan–US alliance for the stability and prosperity of East Asia and the world economy. At the end of the Cold War, many on both sides considered the alliance a relic of the past; in fact, it is vital for the future.

US administrations once hoped that China would become a ‘responsible stakeholder’ in the international order. But President Xi Jinping has led his country in a more confrontational direction. A generation ago, the US supported China’s membership in the World Trade Organization, but there was little reciprocity; on the contrary, China tilted the playing field.

Critics in the US often accuse presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush of naivety in thinking that a policy of engagement could accommodate China. But history isn’t that simple. Clinton’s China policy did offer engagement, but it also hedged that bet by reaffirming its security relationship with Japan as the key to managing China’s geopolitical rise. There were three major powers in East Asia, and if the US remained aligned with Japan (now the world’s third-largest national economy), the two countries could shape the environment in which China’s power grew.

Moreover, if China tried to push the US beyond the first island chain as part of a military strategy to expel it from the region, Japan, which constitutes the most important part of that chain, remained willing to contribute generous host-country support for the 50,000 US troops based there. Today, Kurt Campbell, a thoughtful and skilled implementer of Clinton’s policy, is the key coordinator for the Indo-Pacific on Biden’s National Security Council.

The alliance with Japan enjoys strong support in the US. Since 2000, former deputy secretary of state Richard Armitage and I have issued a series of bipartisan reports on the strategic relationship. In our fifth report, released on 7 December 2020 by the non-partisan Center for Strategic and International Studies, we argue that Japan, like many other Asian countries, doesn’t want to be dominated by China. It is now taking a leading role in the alliance: setting the regional agenda, championing free-trade agreements and multilateral cooperation, and implementing new strategies to shape a regional order.

Former prime minister Shinzo Abe spearheaded a reinterpretation of Article 9 of Japan’s post-war constitution to strengthen the country’s defence capabilities under the United Nations Charter, and, after Trump withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, he preserved the regional trade pact as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. Abe also led quadrilateral consultations with India and Australia on stability in the Indo-Pacific.

Fortunately, this regional leadership is likely to continue under Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, who was Abe’s chief cabinet secretary and is likely to continue his policies. Common interests and shared democratic values form the bedrock of the alliance with America, and public opinion polls in Japan show that trust in the US has never been higher. It’s not surprising that one of Biden’s first calls to foreign leaders after his inauguration was to Suga, to assure him of America’s continued commitment to strategic partnership with Japan.

The Japan–US alliance remains popular in both countries, which need each other more than ever. Together, they can balance China’s power and cooperate with China in areas like climate change, biodiversity and pandemics, as well as on working towards a rules-based international economic order. For these reasons, as the Biden administration develops its strategy to cope with China’s continued rise, the alliance with Japan will remain a top priority.

US$12 billion (A$15 billion) is not a lot of money for developing a fighter jet. But it turns out to be a steep bill if you build only 90 units.

Yet Japan has decided it has little choice but to spend that money to create a combat aircraft for the 2030s. The government is going ahead with its F-X program, though work has not passed what is usually regarded as the critical point of commitment, the launch of full-scale development. It is close, however.

Lockheed Martin will backstop Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) in overall development of the F-X, according to a defence ministry announcement made on 18 December, but other companies from the UK and the US will help with propulsion and avionics. The F-X will almost certainly have strong technological links with the British Tempest fighter program, which has a similar timescale for entry into service.

Lockheed Martin or its rival Boeing was always most likely to be chosen as the lead technology support company to help MHI, because Japan relies on the US for protection. The other contender was BAE Systems.

The development budget hasn’t been announced but it was leaked to the Kyodo news agency and the Tokyo Shimbun newspaper: at least ¥1.2 trillion (A$15 billion). This is more than the A$11 billion that South Korea is budgeting for its KF-X fighter, but modest compared with the US$72 billion (in fiscal 2012 dollars) that the US expects finally to spend on F-35 development.

The problem is that Japan is reportedly aiming to build only 90 F-Xs. If so, the development cost per aircraft will be about A$170 million—an enormous amount even if some of that is the result of inflation. Unit production costs should be spectacular, since the fighter will be unusually large and its factories won’t get far down the learning curve before the program finishes. Also, Japan likes to build aircraft slowly (and therefore inefficiently), to keep factories working.

The defence ministry in Tokyo has been pushing and preparing for more than 10 years to build an indigenous aircraft to replace the MHI F-2 strike fighter. The government, after considering direct importation or collaboration in foreign programs, decided in 2018 to go ahead with a Japan-led effort.

It had good reasons for doing so, though the decision will have to be judged finally against the unit cost of each aircraft. The three best justifications for developing the F-X are that Japan wants full control of the configuration, the next US fighters won’t be available for export, and Japan needs a design that may not suit other countries.

And, no, just buying more F-35s was never a likely option. Japan wants the first F-X to enter service in 2035, by which time the F-35 won’t be a modern fighter: it will have been operational for 20 years and clocked up 34 years since entering full-scale development.

Also, arms importers dislike the control over equipment configuration wielded by supplier countries, either contractually or by withholding intellectual property. This is especially a problem for a country, such as Japan, that develops its own airborne weapons and sensors and wants freedom to integrate them.

Nonetheless, Japan has previously shrugged and chosen the best that the US has to offer: the F-4 Phantom in the late 1960s and the F-15 Eagle a decade later. But the US refused to supply the F-22 Raptor and cannot be expected to export its forthcoming fighters as soon as Japan needs them, if they are ever exported at all. They are still mostly secret.

Finally, the defence ministry’s studies early last decade came up with an awkward conclusion: that Japan should operate very big, twin-engine fighters to provide sufficient range and endurance. Smaller fighters could be afforded in greater numbers, but, since they would soon run out of fuel, fewer would be available on station.

The result is that the ministry’s F-X design concepts are enormous: larger than the F-22, which has an empty weight of 19.7 tonnes. (The F-35A, which is not a small aircraft, is only two-thirds as heavy as the F-22.) The F-X is shaping up as so a big a brute that I have suggested the nickname ‘Godzilla’.

The size decision is awkward, not only because bigger aircraft cost more to develop, but because Japan cannot rely on other countries agreeing as partners to build something similar. The two programs into which the F-X could have been merged were the UK’s Tempest and (apparently never seriously considered) the French–German–Spanish Future Combat Air System. Early concepts for both have indeed been large, but neither is close to program launch and either could easily be trimmed before a final design is chosen. Japan wants to get moving now.

Still, Japan will probably save some money by sharing systems with the Tempest. After long and often unsatisfactory experience in multinational aircraft development, London has determined that it won’t spend years in negotiations with partners to agree on developing a common aircraft that none would be happy with. Instead, the model is an invitation for other countries to cooperate as far as suits them. They would not need even need to use the same airframe. This is good for Godzilla.

For example, Japan can build its big, bespoke airframe but use an engine that can be developed by its own IHI Corporation and Rolls-Royce, and also be used in the Tempest. Indeed, Rolls-Royce has proposed exactly that, noting that Japan has useful materials technology.

Britain and Japan are already working on applying an advanced radar technology, element-level digital beam forming, to aircraft. And they are developing a version of the MBDA Meteor missile with an active, electronically scanned array.

Still, Japan has awarded its first prize to Lockheed Martin, which will work with Northrop Grumman in supporting MHI on the overall integration of the F-X. Lockheed Martin has become the most practiced of any company in supporting foreign fighter development: it stood behind MHI in developing the F-2 and is doing the same job with Korea Aerospace Industries on the KF-X.

Since finalisation of a concept design has been awaiting input of the top-level integration partner, F-X development cannot yet be fully launched. But the parliament this month allocated ¥73.1 billion to the program for the fiscal year beginning April 2021, suggesting that it is about to get fully underway.

Shinzo Abe was born into Japan’s political royalty. His maternal grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, barely escaped trial as a Class-A war criminal yet he served as prime minister from 1957 to 1960. His paternal grandfather, Kan Abe, served in parliament and his father, Shintaro Abe, was foreign minister. With two terms, 2006–07 and 2012–20, Abe was Japan’s longest-serving prime minister. When he resigned on 28 August for health reasons, his popularity was sliding, he was mired in a succession of scandals, and his vim and magic touch had deserted him.

The next general election is due in October 2021. New prime minister Yoshihide Suga doesn’t hail from a political dynasty and has no powerful factional base. His ascent reflects the priority given to stability and continuity in these turbulent times in domestic and global affairs as geopolitical tensions, the coronavirus pandemic and economic downturns roil most countries.

Abe’s foreign-policy and national-security accomplishments will be key parts of his enduring legacy. Few countries have benefited as much as Japan from the post-1945 liberal international order. Abe worked hard to position his country as a solid pillar of that order, its economic weight providing ballast to the order and its commitment to a rules-based world operating as a stabiliser.

Abe memorably declared in Washington in February 2013 that Japan was back, saying: ‘Japan is not, and will never be, a tier-two country.’ He was fully vested in efforts to revive Japan’s ailing economy; stand up to China on disputed island territories while trying to engage with Beijing to address mutual concerns; deepen the US alliance; increase defence spending; and change the peace constitution by stealth. His conservative vision was tempered by a pragmatic streak that put a premium on advice from trusted experts.

Abe had to contend with the nationalistic, protectionist, transactional and erratic Donald Trump; the relentless rise of China; the transformation of the US–China relationship from strategic engagement to full-spectrum confrontation; and the expansion of strategic horizons from the Asia–Pacific to the Indo-Pacific. To navigate these shifting cross-currents without capsizing the Japanese ship of state, Abe also had to nudge the people into accepting a continual reinterpretation of the constitutional limits on Japan’s security preparedness and policies.

The alliance with the US is Japan’s pre-eminent national security priority. Kishi was instrumental in revising the US–Japan security treaty in 1960 to strengthen the military alliance. Kishi’s dream of restoring Japan’s full independence continued to motivate Abe’s vision of strengthening military links with Washington to insure against a collapse of the Pacific military balance. Abe worked to ensure modern Japan played what he regarded as its proper part in Asia and the world by amending the constitution to permit a more active national and collective defence role, and generally ending Japan’s defensiveness and apologetic pursuit of a foreign policy that advanced its national interests.

Abe invested more heavily than any other world leader in cultivating a personal relationship with America’s notoriously mercurial president and became known as the ‘Trump whisperer’. Conversely, Japan is the linchpin of the Indo-Pacific security order and a critical component of the US’s rebalancing strategy for the region. Abe was the first world leader to meet Trump after his surprise election and joined India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi as the only two democratic leaders to establish a personal rapport with the volatile president. Yet the ‘bromance’ yielded few tangible rewards, as Tokyo University’s Kiichi Fujiwara noted.

The unchecked nuclearisation of North Korea and the rise of China increased the salience of the US–Japan security treaty. The fear of abandonment by the US is a powerful and constant undercurrent in Japanese foreign policy. Consequently, good relations with China are a hedge against an unreliable US ally in the future.

An unintended outcome of Trump’s weaponisation of tariffs and sanctions to prosecute proliferating US trade disputes was to increase Japan’s leverage at the intersection of geoeconomics and geopolitics. Beijing needs access to Japanese trade, investment and markets to offset US decoupling, while Washington can harness Japan’s potential to check China’s growing influence in the Indo-Pacific.

As the China–US conflict intensifies, Suga will find it hard to maintain Abe’s balancing act. An early test will come with the need to decide on the postponed April state visit by President Xi Jinping. A heavily publicised visit would showcase the failure of US efforts to contain China and hand Beijing a major PR coup, but it would also cause disquiet in Japan’s ruling party. Yet, further postponement would be a public humiliation for Xi and hurt Sino-Japanese ties.

The foreign ministers of the Quad nations—Australia, India, Japan and the US—are scheduled to meet in Tokyo in early October and Suga is expected to meet with them. The Quad has served to highlight the values, interests and priorities that Japan shares with the other three.

In an influential essay in 2012, Abe was the first leader to introduce the conceptual vocabulary of a free and open Indo-Pacific as a way of integrating geography, geopolitics, democratic political values and freedom of navigation around the Indian and Pacific Oceans. On 10 September, India signed a mutual logistics support agreement with Japan, complementing its earlier agreements with the US, France, South Korea and Australia. Australia’s 2016 decision to purchase French instead of Japanese submarines was a major disappointment for Abe, as was India’s defection from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership last year.

Abe is likely to remain a key influence on the conduct and contours of Suga’s foreign policy, ensuring policy continuity and exuding reassurance to diplomatic partners. As chief cabinet secretary, Suga was very much part of the inner circle of all key policymaking and thus already has part ownership of the Abe legacy.

The domestic-policy-focused Suga will have his mind concentrated by the need to steer Japan through the coronavirus crisis back to economic prosperity. With only limited foreign policy expertise, he’d be foolish not to utilise Abe’s experience, skills and personal connections around the Indo-Pacific and the world. In dealings with the likes of Trump, Xi, Modi, Scott Morrison and other G20 leaders, Abe will be a diplomatic asset abroad without constituting a political liability at home. Few world leaders can boast such a political epitaph on leaving office.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s unexpected resignation last month for health reasons has raised many questions about the legacy of the country’s longest-serving premier. One of them is whether his successor, Yoshihide Suga, will be able to continue Abe’s geopolitical balancing act as tensions between China and the United States are continuing to escalate dangerously.

The US and China are critical to Japan’s peace and prosperity. America is Japan’s security guarantor and second-largest trading partner, while China is its largest trading partner and a next-door neighbour. After Abe returned as prime minister in December 2012, he adroitly managed Japan’s relationships with both.

Abe went out of his way to befriend US President Donald Trump, even as Trump claimed that US–Japanese trade was ‘not fair and open’ and demanded that Japan quadruple its contribution to the cost of keeping American troops in the country. He further pleased the Trump administration by quietly banning the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei from participating in building Japan’s 5G network.

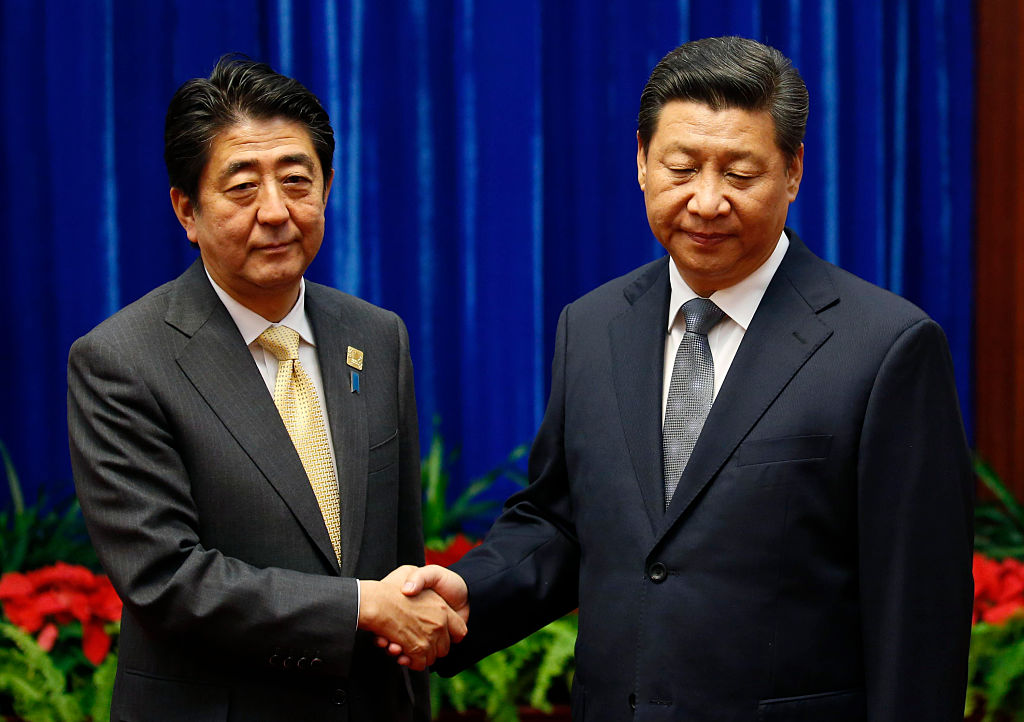

At the same time, Abe also cultivated ties with Chinese President Xi Jinping, and made a diplomatic ice-breaking trip to Beijing in October 2018 for the first Sino-Japanese summit in seven years. With US–China relations in freefall, Xi seized Abe’s olive branch and planned a state visit to Japan in April, which would have been the first by a Chinese leader since 2008. (The visit has been postponed indefinitely because of the Covid-19 pandemic.)

But Suga will find it increasingly difficult to avoid taking sides in the intensifying US–China conflict. In the short term, he will have to make a decision regarding Xi’s postponed state visit. Opposition to the visit runs high within Suga’s Liberal Democratic Party, owing to the Chinese government’s recent imposition of a harsh national security law in Hong Kong. A made-for-TV state visit to Japan would be a huge win for Xi, who is eager to demonstrate that the Trump administration’s containment of China is failing.

Chinese pressure to reschedule the visit will put Suga in a bind. Acceding to China’s wishes would cost him political capital at home but scrapping the visit would humiliate Xi and hurt Sino-Japanese ties. The only thing Japan’s new prime minister can do is to find all the excuses he can to continue postponing the visit for as long as possible.

In any case, tensions regarding a largely symbolic Sino-Japanese summit will pale in comparison with the likely impact on Japan of two US–China disputes in the coming years.

First, the US will call on Japan to tighten restrictions on key technologies it supplies to China. But with more than US$38 billion invested directly in China and nearly 14,000 firms operating there, Japan would find it practically difficult, economically ruinous and diplomatically costly to comply in full with any US sanctions against China.

No one knows how Suga, who was Abe’s cabinet secretary and closest aide for the last eight years, will be able to please the US on the technology issue without angering China, or vice versa. He will certainly face a much harder task than his predecessor, unless the US and China somehow de-escalate their conflict.

Suga will also have a far tougher time sitting on the fence when it comes to security issues. As a member of the so-called Quad—an Indo-Pacific security grouping also including Australia, India and the US—Japan will face US calls to participate in joint naval exercises more often and on a larger scale in order to challenge China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea. Last year, for example, a Japanese aircraft carrier joined US-led naval drills in waters claimed by China.

China did not react strongly to Japan’s participation, owing to the two countries’ improving bilateral ties. But it could lash out against Japan if the rapprochement initiated by Abe fizzles and Suga’s administration starts to collaborate with the US more overtly and energetically in disputes over the South China Sea.

One thing that could completely wreck Sino-Japanese ties in the next few years would be the deployment of medium-range US missiles on Japanese soil. Pentagon strategists are eager to position powerful offensive weapons closer to the Chinese mainland, and Japan is an ideal location.

The missiles are still in development, so there is no need yet for the US to ask Japan to host them. But once America has produced sufficient quantities, it is hard to imagine that it will not press Japan for permission to deploy them. Were Japan to agree, its relations with China could face their worst crisis since the two countries restored diplomatic ties in 1972.

Of course, none of these troubles are Abe’s or Suga’s fault. But they illustrate once again the plight of a country squeezed between two duelling geopolitical giants—and the scale of the diplomatic challenge facing Japan’s new prime minister.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s announcement that he is standing down for health reasons is worrying many across the Indo-Pacific. The US, Australia and Southeast Asia have grown accustomed to Japan’s stronger and ‘sturdier’ leadership under Abe. In turbulent times, many major powers often disappoint with their leadership styles, but Abe stood out as a pillar of stability and even sanity.

Abe’s eight-year second term as prime minister is a central, positive reason why Japan is the most trusted major power in Southeast Asia. Japan is the first country most Southeast Asian states look to for assistance in navigating between a more aggressive China and an unpredictable America. In the escalating US–China competition, when it comes to Southeast Asia, Japan is the winner.

Abe has been most effective when leading ‘quietly’, yet meaningfully, on issues of shared interest. This was not always the case. Abe’s engagement with Southeast Asia over the past eight years exemplifies the benefits of second chances. In his one-year first term as prime minister in 2006 and 2007, Abe’s approach to foreign policy left many in Southeast Asia uneasy. His desire to make Japan a ‘beautiful country’ again and his patronage of Yasukuni shrine in Tokyo stirred painful memories of Japan’s conduct in Southeast Asia during World War II.

Current deputy PM and former foreign minister Taro Aso’s 2007 vision of a Japan-led ‘arc of freedom and prosperity’ from northern Europe through Southeast Asia to Japan and Taiwan was widely viewed as a campaign to gain Southeast Asian support to encircle China. Any proposal, real or inferred, to collaborate in directly challenging China unifies the diverse states of the region in opposition.

In his second term as prime minister, with a few exceptions, Abe has engaged with Southeast Asia more effectively. In 2012–13, despite the difficulties Japanese prime ministers face leaving parliament, Abe visited each of the 10 Southeast Asian states, some more than once.

While the foreign policy beliefs and goals haven’t changed, the second Abe administration has been better than the first at gaining Southeast Asian support for the policies developed to advance them. Japan’s Partnership for Quality Infrastructure, which is focused on Southeast Asia and backed by significant concessional financing, presents an attractive alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

The free and open Indo-Pacific, or FOIP, concept coined by the Abe administration, and promoted also by Australia, India and the US, has had a lukewarm reception in Southeast Asia since the Trump administration adopted it in 2017. But of all the different versions of the Indo-Pacific concept, Southeast Asians align closest with the one championed by Japan. Though marked by comparatively fewer declaratory pronouncements and policy papers, Japan’s FOIP has been the most advanced in terms of action. Released last year, the ASEAN outlook on the Indo-Pacific refers, similarly to Japan’s FOIP, to the UN development goals and building connectivity and prosperity.

Japan remains the key balancing actor in the Mekong subregion where China dominates its smaller neighbours. Japan’s help through bilateral development assistance, multilateral institutions and energy and infrastructure investment is critical for overcoming the subregion’s sustainability challenges.

Under Abe, Japan also has become a champion of free trade. The US and China are engaged in a trade and technology war that undermines the global supply chains that gird Southeast Asian trade. Among Donald Trump’s first decisions as president was to withdraw the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the world’s largest trade deal. Japan has taken the leadership in continuing the TPP after the US withdrawal, now the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. This support was not only greatly appreciated by the Southeast Asian members of the TPP, but also asserted Japan’s leadership globally.

Japan has also advanced its critical role at sea, actively supporting Southeast Asian nations with maritime awareness capacity-building. The Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei have all hosted regular naval visits and training, engaged in exercises and, in some cases, received patrol boats from Japan, all very well received amid mounting challenges in the South China Sea.

All of that has earned Japan solid trust in the region. Surveys have found that Japan is by far the most trusted major power by people in the 10 Southeast Asian countries. Confidence in Japan continues to strengthen, while confidence in both China and the US sharply declines—testimony to the fact that long-term efforts and commitments are needed to earn trust. Abe’s approach to Southeast Asia stands out from more transactional ones favoured by Beijing and Washington.

Abe’s diplomatic acumen is another reason why many in Southeast Asia, and South Asia and Oceania, look up to him. He is among very few global leaders who have dealt with both Xi Jinping and Trump with some success—two relationships that are vital for Japan and are asymmetric and fragile for different reasons.

Abe’s most important legacy may be in the foreign policy arena: he strengthened Japan’s international reputation. Today, Japan is the partner of choice of most countries in the Indo-Pacific, with exception of some of its Northeast Asian neighbours, and has positioned itself as a credible, reliable pole in the evolving multipolar world.

Shinzo Abe’s sudden resignation on health grounds ends the tenure of Japan’s longest-serving prime minister. The country’s most internationally recognised statesman since 1945, Abe has been, among other things, the world leader most keen on playing golf with US President Donald Trump.

Though he leaves Japan with a still-weak economy, Abe has made his country stronger and more autonomous in matters of defence and foreign policy. Whoever succeeds him will likely continue on that path, which is good news for proponents of peace in East Asia and of the rules-based international order more generally.

Abe’s current term was set to end in September next year, but his approval ratings had fallen to historic lows, making another run for the premiership a non-starter. The manner of his departure, after nearly eight continuous years in office, thus reflects an old principle of political life. For a long-serving party leader who knows the end of his political career is nigh, it is better to set the terms of one’s own departure than be pushed out by dagger-wielding rivals.

Since his youth, Abe has suffered from ulcerative colitis, a debilitating condition that forced him to resign once before, in 2007, after serving one year as prime minister. That previous departure also coincided with serious political difficulties, making his return to power in 2012 all the more remarkable. Given two recent well-publicised hospital visits, Abe’s renewed health problems are likely genuine. And yet, with the Tokyo Olympics having been postponed to next year, it’s hard to believe that he would choose to step down now unless he also felt serious political pressure.

From an international perspective, Abe’s loss of popularity may seem surprising, given that his country has suffered fewer than 1,300 Covid-19 deaths and a smaller economic downturn than in the United States or most European countries. But Abe’s government has drawn criticism for erratic communication and a seemingly uncaring economic response to the pandemic. And, after so many years in office, accumulated scandals and a general weariness with the country’s unchanging leadership have caught up with him.

Moreover, there has been growing disappointment about the state of the economy and living standards. Abe’s much-touted economic program, known as Abenomics, has consisted of faster monetary expansion, some fiscal stimulus and talk of pro-growth structural reforms. But the results have been meagre, especially from a leader who has won three general elections and long enjoyed strong parliamentary majorities.

Abenomics was billed as a program to overcome deflation, accelerate economic growth, and—in a second phase—boost Japan’s birth rate. While prices have stopped falling, hopes of restoring mild inflation and wage growth have been dashed. While economic growth between 2012 and the current pandemic was slightly better than in the previous decade, that was largely owing to the absence of major shocks on the scale of the 2008 financial crisis or the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. The birth rate remains flat.

To be sure, the Abe government has enacted some small, useful reforms, including a new corporate-governance code, better disclosure rules for companies, higher childcare spending and tighter limits on dangerously long overtime. But plans for deeper reforms to increase competition have either not materialised or been blocked by vested business interests. Nearly 40% of the workforce remains on short-term, precarious contracts, and although more women work, very few have broken through to leadership positions.

Abe has also failed to achieve his greatest ambition of all: revising Japan’s 1947 constitution to normalise the status of the country’s armed forces and remove the document’s famous pacifism clause (Article 9). The Japanese public remains opposed to such a change, and Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has commanded its strong parliamentary majorities in coalition with the centrist Buddhist group Komeito, which has pacifist roots. Because a constitutional revision requires a two-thirds majority in each house of parliament and a simple majority in a national referendum, Abe has never been able to realise his dream.

As for his legacy, Abe will be remembered as a traditionalist (in Japanese terms). Within the LDP, he leads a group of ‘new conservatives’ who advocate a strong state, central leadership, established values and—most of all—a more robust and autonomous foreign and defence policy. On these priorities, he has delivered.

At times, he has pursued a slavishly close relationship with Trump. But he has also sought to carve out a more autonomous role for Japan on issues like trade. In 2017, he led the effort to salvage the 12-country Trans-Pacific Partnership following the Trump administration’s withdrawal from that deal. Japan has also negotiated a free-trade arrangement with the European Union and will shortly complete a parallel deal with the United Kingdom.

Abe has also strengthened Japan’s defence relationship with India. By emphasising a revisionist view of Japan’s wartime history, however, he has brought relations with South Korea—Japan’s closest neighbour and a fellow US security ally—to a new low following that country’s leftward turn.

The race among potential successors within the LDP has been covertly underway for several months. But it’s already clear that none of the leading contenders—Defence Minister Taro Kono, former foreign minister Fumio Kishida, Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga, nor even Abe’s old rival Shigeru Ishiba—will want to soften the country’s foreign-policy stance. If anything, they may compete to appear even stronger on security issues, advocating more military spending, pre-emptive strike capabilities against North Korean missile threats, or tougher action against Chinese maritime incursions in the East China Sea.

No Japanese prime minister since the end of the American occupation in 1952 has been able to contemplate seriously any kind of rupture with the US. But, recognising that America has become a less reliable and cooperative ally, especially under Trump, Abe has prepared the ground for Japan to develop a more independent voice as it builds its own network of partners around the world. That strategy is here to stay.

Today, on the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II, questions remain about what stopped the Japanese from invading Australia, and how it was that many of our personnel came home alive and unwounded despite the dreadful conditions they faced.

The answers largely define an achievement of Australia’s World War II generation.

Although Australia had thousands of airmen serving Britain in Europe and the Middle East, and three infantry divisions in Egypt and Palestine, these contributions to the British war effort were a down-payment for British protection against Japan, the only nation with the capability and intent to directly threaten Australia.

The fall of Britain’s defence shield, Singapore, to Japanese forces in mid-February 1942 has convinced Australians that their nation was left defenceless, and was only saved from invasion because of American assistance and a Japanese agenda to finish the war in China.

In reality, the opportunity to secure the southern flank, of all their conquests, would have been irresistible to the Japanese, and good military strategy. The only aid that Britain and the US were able to send was General Douglas MacArthur. No significant American forces reached Australia until well past that critical phase of the war (February to June 1942).

Something was happening in Australia that caused Japan to reject invasion, as it did in late February 1942. The opportunity to invade a defenceless Australia would never have looked more viable.

Australia had just completed its industrialisation in 1939. From 1919, Australian governments had fought off the determined efforts of the great economic powers to prevent that happening. But by combining with industrial companies such as BHP, and Collins House, and using its own technical organisations such as the Munitions Supply Board of the Department of Defence, Australia created the key industries required.

By December 1941, the nation had been in a full war economy for 18 months, and by March 1942 had created enough armaments to fully equip six infantry divisions. These units were equipped to fight German panzer divisions, and were twice as powerful as Japanese divisions and much more mobile. Their artillery was twice the strength of Japanese field artillery and outranged it. The Australian 2-pounder anti-tank guns outranged all Japanese tanks in Southeast Asia and could penetrate their armour, making it disastrous for any tank force.

The scale of Australia’s armament program is recorded in the monthly reports of the director-general of munitions and backed up by similar monthly reports from the army on what it was receiving from the department. Both were war cabinet documents. By June 1942, Australian production had equipped eight infantry divisions with modern weapons.

Having had diplomatic representation in Australia until December 1941, Japan was most likely well informed, in general terms, about Australia’s burgeoning industrial war economy, which, apart from its own, was unique in the Pacific and Southeast Asia.

In late February 1942, the Japanese army and navy discussed an invasion of Australia. Although the navy was enthusiastic, the army put forward a military appreciation which dismissed the idea as far too dangerous.

It recognised that Australian forces were likely to be better armed than the Japanese divisions, and more mobile. The appreciation said an invasion would require a minimum of 12 divisions. This force could not be provided from existing resources without weakening Japan’s hold on its conquests, and it might still be defeated by the aggressive Australians defending their homeland. The Japanese army rejected the navy’s suggestion. The idea was never considered seriously again by the Japanese.

Australian scientists, technocrats and industrialists had created so much equipment that Japan could not supply the volumes of its own materiel to overcome it. Japanese airpower could not redress this imbalance because it had not developed effective close air-to-ground support for its troops and had to face heavy Australian anti-aircraft defence. The Japanese were also aware that Australian strength in fighter aircraft was increasing steadily, and that radars were spread up the east and north coasts of Australia. Thus, Australia’s greatest strategic victory in World War II was achieved by science, technology and secondary industry.

The US naval victory at the battle of Midway, in early June 1942, removed the Japan’s capability to invade Australia by destroying its main aircraft carriers. This made it safe for Australia to begin to transfer military power to fight the Japanese in Australian Papua and New Guinea. Australia had to re-equip its army to cope with the corrosive jungle environment and extremely steep and rugged terrain. The battles took place in terrible conditions, which should have favoured the Japanese defenders. A stalemate was the most likely result, with heavy casualties on both sides, which the Japanese were willing to accept.

The early battles followed this pattern. But Australia had organised its scientific and technical resources far more efficiently than Japan. By mid-1943, Australia had become, for the allies, the centre of research into jungle organisms and jungle-proofing of all weapons and equipment. A flood of new equipment, specially treated clothing and food, and a vastly superior medical support system with Australian-made drugs and antibiotics swung the struggle in the jungle decisively in Australia’s favour.

Japanese battle casualties in the Southwest Pacific inflicted by the Australians were well over 50,000, whereas Australian battle casualties were 14,700. Japanese deaths from disease and starvation in the same area were over 100,000. Australian deaths from the same causes were about 1,000.

At this ratio of 1:3, Australian battle losses were the opposite of the classical ratio for an attacking force encountering a well-prepared defence, in rugged, well-covered terrain. The Australians reversed this loss ratio through better-designed weapons, better communications, better-quality ammunition and flexible battle tactics. Japanese weapons were poorly designed for jungle warfare in equatorial regions, their ammunition and communications were degraded by jungle organisms, and their battle tactics were often inappropriate for the conditions and terrain in which they fought.

The extraordinary imbalance in deaths caused by disease and starvation was a direct consequence of the Japanese army’s lack of logistic and medical support for its troops. Before World War II, Japan had conducted nearly all its campaigns in well-populated and productive environments such as China and Manchuria. These environments were not particularly unhealthy, so it could get away with a rudimentary medical system. Similarly, food could be taken from the local populations, so Japanese forces did not need an elaborate logistic support system.

When Japan began its Kokoda campaign, it needed to sweep away the opposition quickly, before disease took hold in Japanese troops and they exhausted their rudimentary food supplies. They could not rely on getting food from the sparse local population.

Although it took some time to organise, by early 1943 the Australian logistic system provided good medical support and increasing amounts of food.

The result was devastating, because nearly all of Japan’s post-Kokoda campaigns in Southeast Asia were conducted in jungle environments with sparse populations, which dramatically exposed logistic and medical deficiencies.

The impact of Australian science, technology and secondary industry on the survivability of Australian troops can be calculated roughly. Australian forces might have expected a minimum of around 45,000 casualties, given that they were trying to drive the Japanese out of very formidable defensive positions. If the Japanese had been able to prolong their resistance, this would have produced a situation like many World War I campaigns and caused Australian casualties as high as 80,000. The impact on Australia would have been enormous.

Australia’s war economy also provided vast amounts of clothing to hundreds of thousands of American service personnel in the Southwest Pacific. Huge quantities of basic materials for road and base building, as well as armaments, transport and signal equipment, were also supplied. In 1943, Australia supplied 95% of the food for 1,000,000 American servicemen. In commenting on this wartime support, President Harry Truman wrote in his 1946 report to the US Congress on the Lend-Lease Act, ‘On balance, the contribution made by Australia, a country having a population of about seven millions, approximately equalled that of the United States’.

This extraordinary result highlighted the monumental achievements of Australia’s World War II generation. Clearly, Australian governments of the 1930s regarded defence preparations as being more than the accumulation of armaments, which then rapidly became obsolete. They chose to put their effort into the development of secondary industry, which advanced national development and immigration, but also provided a huge amount of flexibility in what could be produced to arm the nation in an emergency.

They did this in a way that deserves much greater recognition.

When Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s term ends in late 2021, it will be almost nine years since voters returned his Liberal Democratic Party to government in Japan’s 2012 general election. Abe promised to rescue Japan from its lost decades of low growth and deflation, improve crisis management, and strengthen Japan’s influence in world and regional affairs by making it a ‘proactive’ contributor to international peace and security. Japan, according to Abe, ‘was back’.

But given the already precarious state of Japan’s economy prior to the coronavirus crisis, and the government’s muddled managing of Covid-19’s impacts on public health and the economy, it’s likely that voters will mark the administration down to a ‘fail’ on two policies they most care about.

Abe is on relatively strong ground with his foreign policy approach, but his government’s shortcomings on the economy and crisis management fronts may ultimately threaten his vision of a more proactive Japan. That would be bad news not only for Japan, but also for Australia and the region.

According to the Abenomics faithful, Abe’s three arrows, launched back in 2013, are still in flight. GDP and inflation growth are often highlighted as evidence that arrows one (quantitative easing and asset buying) and two (massive spending) haven’t yet disappeared into the undergrowth. By 2019, however, many observers were becoming increasingly doubtful about where Abe’s arrows were actually headed.

Overall, the results have been mixed at best and, by late last year, downright worrying. Japan’s average annual GDP growth since 2012 had not been more than around 1.3% before it took a dive in late 2019 to –1.8%, just before the coronavirus outbreak. Japan’s public debt, meanwhile, has grown to nearly 240% of GDP and now looks set to blow out even further.

Adding further to Japan’s woes is its biggest economic bogeyman, deflation. After a series of intermittent jumps to around 1% over recent years, the fall in prices appears to have stopped, but only just. The inflation rate last December again sat perilously close to zero at only 0.4%. Puzzlingly, even though Japan has been experiencing a labour shortage since 2017, real wages have hardly changed in 30 years. One likely explanation is the stiff headwind encountered by Abe’s third arrow: structural reform.

Japan’s private sector has stubbornly resisted structural reform on most fronts. Government efforts to create more transparency in corporate affairs, provide better and more equal opportunities for women, and wind back the long-held practice of rewarding seniority over achievement have made little or no progress. Productivity remains very low (Japan is 21st in the OECD and the lowest among G7 economies) and the threat of karoshi (death from overwork) remains very real for many.

As a result, many Japanese companies and offices remain inefficient and well behind the technology curve, while workers still endure excessive, and mostly unproductive, overtime expectations. Company, and government, offices continue to rely on fax machines and the use of hanko (official seals).

Legislation intended to protect workers from overtime abuse, meanwhile, merely limits overtime to 100 hours per month. Pre-Covid-19 calls for companies to adopt more flexible working hours and teleworking fell on deaf ears, as the large numbers of people still travelling to work during the pandemic demonstrated. By 20 April, only 18% of workers were staying home.

While better implementation of third arrow reforms, especially in the workplace, certainly would have helped to contain the coronavirus and lessen its economic impact, most of the responsibility for the virus’s spread lies with the government failing the first real test of Abe’s commitment to improve Japan’s crisis management capabilities. Indeed, his leadership reflects many of the problems and mistakes made by US President Donald Trump, and public confidence in the government’s ability to respond is rapidly fading.

Like Trump, Abe was slow to close borders. He prioritised economic impacts over health measures, sent confused public messages and largely failed to coordinate an effective national response with prefectural governments.

The many costly missteps included the health ministry’s inability to quarantine infection early on the Diamond Princess cruise ship and to carry out sufficient testing. These failings paint a telling picture of crisis mismanagement similar to the institutional paralysis that plagued the Democratic Party’s widely criticised handling of the Fukushima nuclear crisis in 2011.

In contrast to Abe’s wayward arrows and the mounting domestic problems caused by incomplete policy implementation, Japan has become more proactive and influential in international affairs under his leadership.

Abe’s legislative changes and agreements allowed increased security cooperation with the US and other states (beyond just disaster management), in particular with Australia. His leadership helped save the Trans-Pacific Partnership from Trump’s ‘America first’ posturing, and revive the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue. These are compelling examples of how much Japan’s foreign policy and defence capabilities have changed under Abe.

However, Abe’s foreign policy successes may soon be threatened by his inability to make Japan less vulnerable to external shocks like Covid-19. A bigger concern is whether states, especially democracies, will become more inward-looking as they seek to recover from the huge economic and human costs of the pandemic, which are likely to continue for some time.

If so, the resources for Japan’s more proactive foreign and defence policy approach, in particular funding for foreign aid, may well shrink again, as it did during the late 1990s and 2000s.

The potential costs of Japan becoming less involved in the region go well beyond Abe’s place in the history books, particularly in light of China’s growing belligerence, Trump’s increasingly dangerous unpredictability, and the even more unstable post-pandemic world that likely awaits us. In the absence of US leadership, Japan has stepped up to support the existing order by building closer relations with like-minded states and promoting multilateral cooperation and engagement.

Whether Japan can, or will, continue to do so while trapped in a deep recession without any means of escape—thanks to another decade of lost opportunity for reform—however, is far from clear. But the implications of Abe having presided over yet another ‘lost decade’ will be felt not only by Japan, but by the entire region.

If the Japanese government’s performance in dealing with the threat of the novel coronavirus Covid-19 is any indication, the upcoming Tokyo Olympic Games are doomed to fail even before they begin. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is preparing emergency legislation and a majority of schools are now closed, as Abe requested, for around a month in an effort to contain the spread of the virus. But the move is too little, too late.

The scary truth is that no one is in charge of managing Japan’s response to the coronavirus.

Bureaucrats have failed to put together a competent team or provide transparent reports about decision-making processes. Meanwhile, political leaders have made themselves look busy by jumping from meeting to meeting and repeating experts’ statements to the press instead of making the difficult decisions that are becoming increasingly urgent.

The contrast between Beijing and Tokyo is striking and unflattering to Japan. Downtown Beijing is deserted as people try to avoid spreading the virus by staying home. Tokyo looks like business as usual, with trains and subways still packed.

The Japanese government has shifted its efforts to contain the spread of the virus from seaports and airports to focusing on communities and asking people to stay at home. But the messages have been mixed. The media remains optimistic, reporting that the virus is mild and will likely taper off as summer arrives. As a result, not all local communities are adhering to Abe’s request to close schools. There’s little detailed symptom data available from authorities and doctors. Only healthcare workers are voicing real concern, while the public struggles to judge how to protect itself from this ‘very mild’ yet deadly virus.

This is not to downplay the efforts of the individual authorities who are engaged at the frontline. The emergency budget of US$138 million—though far less than emergency funding in the United States—is a significant step forward, helping to produce more testing kits, secure more beds in health facilities and fund research about the virus. But what’s lacking is coordination and leadership.

Bureaucratic silos have resulted in parallel taskforces and meetings convened by the prime minister’s office, the cabinet office, the ministries of health, labour and welfare, and the Tokyo metropolitan government. Health experts and officials from various agencies debate the same topics repetitively in multiple meetings, while Abe has put no one in charge.

Arbitrary bureaucratic interference is preventing authorities from implementing a desperately needed nationwide effort that includes the best experts from academia, research centres and industry. The National Center for Global Health and Medicine—one of the main research centres for infectious diseases—wasn’t invited to be part of a crucial taskforce. There have also been delays in rolling out favipiravir, the antiviral drug being developed by Fujifilm that could be effective against the virus, because it was approved only as a treatment for influenza and not Covid-19.

Lessons learned from past crises in Japan such as the 2011 tsunami and Fukushima nuclear disaster appear to have been forgotten. Japan’s civil service lacks institutional memory as the system circulates bureaucrats from one position to another every two years and prioritises internal incentives on addressing domestic issues rather than on building global networks. The recommendations from the first-ever independent investigation committee of the Diet haven’t improved the system, and nor have they changed the mindset of the policy elite.

This time of crisis is a chance for Japan to develop innovative solutions to these complex challenges. But the authorities are blindfolded within the existing jurisdiction-based framework and continue to misallocate resources and prevent cross-sector collaboration.

The National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID) was solely designated to produce diagnosis kits and to handle testing because it sits under the Health Ministry’s supervision. But NIID is not the most productive device maker and its testing method takes at least six hours to produce a result. The institute originally had the capacity to conduct only 200 tests per day. It was able to increased that to over 400 tests per day when it introduced three-shift operations to run 24-hour testing. But by early February NIID was crying out for help to increase its capacity, prompting the government to finally go to the private sector to produce faster testing devices in late February.

The authorities could have turned to the private sector for help from the beginning; there are many efficient device makers in Japan that would have responded to incentives for quick and effective diagnosis kits. The hesitation to give the antibody to private makers has resulted in a severe shortage of testing capacity across the country.

The absence of appropriate risk communication is feeding confusion and even hysteria in foreign media coverage of Japan’s response to the crisis. The chain of command is vague and bureaucrats have incentives to cast aside things that are not written in the rules, further delaying responses.

The good news is that despite all the mishandling and delays, the majority of Japanese people still trust the government and try to follow its instructions. Local institutions and individuals are taking serious prevention measures, even as the Japanese leadership is failing to manage the situation.

Before it’s too late, the authorities need first to designate a person in charge, and second, to provide reliable data and patient symptom information in a timely manner so that communities can fight the virus effectively.

The world is watching to see if the Japanese government can step up and show the commitment needed to overcome this enormous challenge ahead of the Olympics.

After the gains made by former US vice president Joe Biden in the Democratic primaries on Super Tuesday, Senator Bernie Sanders is slightly behind but still a frontrunner for the party’s nomination to face President Donald Trump in November. If Sanders does end up as the Democrats’ standard-bearer, this year’s presidential election will be a choice between his left-wing brand of populism and the right-wing variety espoused by Trump.

For Japan, the potential implications of such a contest could be huge. Since taking office, Trump has consistently shunned multilateralism and pursued a divisive domestic agenda that is contributing to a further hardening of partisan attitudes in the United States. Sanders, meanwhile, seems to share Trump’s protectionist instincts regarding trade.

Japanese political and business leaders are especially concerned by the decoupling of economic ties between America and China, the country’s two biggest trading partners. A breakdown in US–China trade relations, or a proliferation of protectionist measures around the world, would disrupt global supply chains and could have a devastating impact on Japan’s economy, the world’s third largest. On China, Democrats don’t appear overwhelmingly different from Trump and the Republicans.

Sanders has blamed trade agreements for eliminating millions of US jobs, and has voted to pull the US out of the World Trade Organization. And Biden, a moderate and Sanders’s main rival for the Democratic nomination, has criticised the manner in which the Trans-Pacific Partnership was drafted, despite having previously promoted the deal.

Nonetheless, Japan maintains some significant strengths. After Trump withdrew from the TPP in early 2017, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe led the pact’s remaining signatories to conclude the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership instead. And a free-trade deal between Japan and the European Union entered into force last year.

Furthermore, Japan’s relatively high standing with ASEAN states boosts its chances of playing a greater global leadership role. In fact, one recent regional survey measuring perceptions of trust in major global powers found that Japan ranked well ahead of the EU, the US, China and India. And among respondents who said they distrusted Japan, the most common reason given was that the country lacked the capacity or political will to act as a global leader.

Japan therefore should build on the trust it enjoys in Southeast Asia, because closer ties with ASEAN are intrinsically valuable and will also better position Japan to engage with the EU. But if Japan is to become a more established vanguard of the rules-based multilateral order, it must act as a rule-shaper and proactive stabiliser. For example, Japan should seek to use its recent large trade deals as leverage to bring the post-Brexit UK into the CPTPP. At the same time, it should perhaps aim to extend its new relationship with the EU to the other CPTPP countries through another pact. This would require aligning CPTPP countries’ policies on critical issues such as data and climate change with those of the EU.

In addition, Japan must help to conclude the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a long-envisaged free-trade agreement between 10 ASEAN member countries and six Indo-Pacific states (Australia, China, India, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand). Such an effort will face headwinds, in particular India’s apparent reluctance to participate in negotiations. India’s withdrawal from the RCEP talks would be a major setback to the Abe government’s free and open Indo-Pacific strategy. For now, Japan must strive to ensure that India can eventually be included in the RCEP if conditions allow.

Finally, Japan and China have agreed on the importance of principles such as transparency and debt sustainability with regard to infrastructure investment, which could provide a window for greater bilateral cooperation based on mutually accepted rules. Although the coronavirus will likely force a postponement of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Japan, the outbreak has heightened a sense of mutual vulnerability. Japanese authorities and companies have provided China with more than two million masks, and Japan is expected to receive at least a million in return from its neighbour. This ‘mask diplomacy’ has had a stabilising effect on bilateral ties.

But although Japan has a wealth of opportunities to help strengthen the liberal international order as a rule-shaper, its ability to do so is still based on its cooperation with the US. And the future strength of that alliance will hinge heavily on how Americans vote come November.

American populism’s gains, on both the left and the right, will further complicate the US–Japan alliance, thus restricting Japan’s role as a rule-shaper. In addition, Japanese policymakers currently must contend with Trump’s obstinacy on the issue of Japan’s host-nation support for US forces stationed in the country, with the administration appearing to press Japan for a massive increase. Democrats will most likely do the same.

In fact, a victory for either Trump or Sanders will raise anxieties in Japan. The US, it is feared, may treat Japan as a strategic bargaining chip should Trump prevail, or grow even more inward-looking if Sanders does. The sort of polarising populism exemplified by Trump, Sanders and several other current world leaders may present Japan and the international order with their biggest challenge of the post-war era.