Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe’s assassination at an election campaign event in Nara is both shocking and puzzling. It is shocking because Japan has known almost no political violence for at least half a century and because gun ownership in the country is tightly controlled. It is puzzling because Abe, having stepped down as prime minister in 2020, had no formal government role; yet the killing was plainly a political act.

Abe’s death is unlikely to have any impact on tomorrow’s elections for Japan’s upper house, the House of Councillors, which the ruling Liberal Democratic Party was already expected to win comfortably. The tragic loss of the LDP’s former leader and prime minister may add some sympathy votes by increasing turnout, but it has primarily astonished and bewildered a country that is completely unaccustomed to such violence.

Abe’s legacy from his record-setting tenure as prime minister—which was divided between an unsuccessful year in 2006–07, followed by a triumphal return from 2012 to 2020—is more notable for its effects on Japanese foreign and security policy than on domestic affairs. To be sure, Abe was a good salesman for his economic-policy agenda, which he successfully promoted under the banner of ‘Abenomics’; but, in the end, it was his foreign policy, not his economic program, that was transformative.

Abe brought clarity, strength of purpose and—by dint of his longevity in office—credibility to Japanese foreign policy. The fact that the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ is now commonly used to describe security and diplomatic strategy in Asia is largely owing to Abe, who took a pre-existing Japanese effort to build a stronger relationship with India and used it to reframe and extend his country’s position both regionally and globally.

That stance was dictated by China’s rise and its increasingly assertive rhetoric and actions in and around the South and East China Seas. Under Abe, Japan committed itself to defining a strategic and diplomatic arena that would be harder for China to dominate. Deepening ties with India was part of that strategy, as were Abe’s efforts to strengthen Japan’s military. He was a leading proponent of proposals to amend the country’s constitution so that its military could play a bigger role alongside that of its key ally, the United States.

Abe was undeniably a nationalist. He originally courted controversy with somewhat revisionist views about Japan’s wartime history, especially regarding the hot-button issue of ‘comfort women’ whom the Imperial Japanese Army forced into sexual slavery in occupied countries. Once in office, however, he largely played down his earlier views. Moreover, he built closer and deeper diplomatic relationships across Southeast Asia, improving ties even with the country’s prickliest neighbour and former colony, South Korea. While relations with China were often tense—especially when Abe visited Japan’s controversial Yasukuni Shrine for its war dead—Sino-Japanese dialogue was nevertheless maintained.

It is always difficult to guess the motives of a lone assassin. The man arrested for Abe’s murder, 41-year-old Tetsuya Yamagami, appears to have used a large, homemade shotgun. Given that Japan is one of the world’s safest countries, security at political events tends to be light, even for a former prime minister, which presumably explains how the gunman was able to pull it off.

According to news reports, Yamagami served for three years in the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force, until 2005. While the motive for the killing is not yet clear, Yamagami reportedly told police he held a ‘grudge’ against a group he believed Abe was connected to.

Although Abe was no longer in office, he was undoubtedly still the country’s most prominent and well-known advocate of a stronger military capability and efforts to revise Article 9 of the constitution. In that capacity, he often expressed a determination to complete the work started by his grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, who, as prime minister in 1960, shepherded through a revision to the country’s security treaty with the US, with a view to reinforcing Japanese defence.

Sadly, it is perhaps not coincidental that the last Japanese prime minister to fall victim to a violent attack was Kishi, who was stabbed by an assailant six times shortly after the revised security treaty was approved. Unlike Abe, however, his grandfather survived.

Australia is removing the qualifications from its quasi-alliance with Japan.

The visit to Japan by Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles is another step in the fading of the qualifiers: ‘quasi-alliance’, ‘small “a” ally’ and ‘alliance lite’.

The qualifiers apply because this is a pact without a treaty—no formal pledge to go to war together.

The quasi-alliance moniker describes the third leg of the trilateral, supporting the US–Japan alliance and the US–Australia alliance.

The small ‘a’ and lite descriptors fade because over the past two decades Japan has risen to become a defence partner for Australia that ranks beside New Zealand and Britain.

Japan sits on the second tier, with the traditional Anglo allies, below the peak where the US presides as the prime and paramount ally. The chatter grows about whether to admit Japan to the ultimate Anglo club, the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing partnership, comprising Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the US.

In the first decade of this century, Canberra was the eager suitor, pushing Tokyo to do more, building the Australia–Japan–US trilateral. In the second decade, Japan stepped up under Shinzo Abe, showing uncharacteristic vigour and ambition. This decade is shaping as the moment Japan remakes itself as a military power.

In launching the trilateral in that first decade, John Howard’s government took the lead and Japan warmed slowly. When Foreign Minister Alexander Downer first broached the trilateral with his Japanese counterpart, he was told Australia was too insignificant as a security player for Tokyo to bother. Equally, Canberra was eager to go further than Tokyo in the ambit of the joint declaration on security cooperation that Howard and Abe signed in 2007. Australia wanted a treaty, while Japan would go only as far as a declaration.

In his second coming as prime minister in that second decade, Abe changed much in ways that matter greatly for Australia. The ‘Indo-Pacific’ may have been a US naval theory, but Abe’s adoption made it a diplomatic and military construct with heft; Australia joined Japan as the first adopter. Abe was equally important in growing the trilateral, the second coming of the Quad, and saving the Trans-Pacific Partnership after US President Donald Trump pulled out—a TPP without the US could only exist with Japan at its heart.

The quasi-alliance has its fullest expression within the trilateral. The three defence ministers had their 10th meeting last week during the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore. Their ‘vision statement’ has the now essential language about opposing ‘coercion and destabilising behaviour’ and standing against ‘unilateral attempts to change the status quo by force’, underscoring ‘the importance of peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait’.

To Australian eyes, the trilateral statement now has the same tone and style of an AUSMIN communiqué, with the effort to list ‘concrete’ outcomes such as exercises for interoperability and readiness; coordinated responses to regional disasters and crises; deepened cooperation on maritime capacity building; and a framework for research, development, test and evaluation to advance trilateral cooperation on advanced technologies and strategic capabilities.

When Abe departed the leadership in 2020, Australia confronted the question of how much the quasi-alliance was based on his personality and how much on permanent shifts in Japan’s policy personality. Abe pushed for a stronger, more autonomous Japan rather than a comfortable Japan declining gently into middle-power ease.

The answer offered by Indo-Pacific expert Michael Green in his new book, Line of advantage: Japan’s grand strategy in the era of Abe Shinzo, is that the trajectory is set—the Abe era will last much longer than the Abe tenure.

Green argues that Japan has done more than any other country to devise a strategy to manage China’s rising economic and military power, to ‘compete but not to the death’. Green’s prediction:

From now on for 10, 20, 30 years, people will be referring to Abe’s doctrine and Abe’s approach. There will be variations. There will be changes. There could be big changes if we have war in Asia or if the US retreats from Asia, but I don’t anticipate those. In terms of intent and trajectory, I think Japan will be very reliable and will be a thought leader and will be respected in Asia.

The shape of the Abe era came into sharper focus on 8 June when Japan’s cabinet approved a plan for a massive increase in defence spending from 1% to 2% of GDP. The 2% pledge is buried in footnote comparisons to NATO spending, so the transformation of Prime Minister Fumio Kishida from dove to samurai is still work in progress.

In his speech to the Shangri-La Dialogue, Kishida promised: ‘I am determined to fundamentally reinforce Japan’s defence capabilities within the next five years and secure a substantial increase of Japan’s defence budget needed to effect such reinforcement.’

In tandem with reinforcing its alliance with the US, Kishida said, Japan would strengthen ‘security cooperation with other like-minded countries’. A new era, he said, needed a new ‘realism’.

Kishida noted that Germany had pledged to lift its defence spending to 2% of GDP, adding, ‘I myself have a strong sense of urgency that Ukraine today may be East Asia tomorrow.’

A Japan pushing fast to double its military spending will change much. After Kishida’s speech, the director-general of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, John Chipman, pointed out that if Japan and Germany reached the NATO standard of 2% of GDP for defence, that’d make Japan the third-biggest defence spender in the world, behind only the US and China, while Germany would lift to number four.

Australia’s new prime minister, Anthony Albanese, has already had his first meeting with Kishida, at the Quad summit on 24 May. They are set to meet again at the NATO summit in Madrid in a fortnight’s time.

Just as NATO is always about alliance politics, these days Australia and Japan have their own alliance dialogue within the trilateral with the US.

The Japan–Australia–US–India Quadrilateral Strategic Dialogue, or ‘Quad’, has gained increasing salience in Tokyo’s efforts to advance its own vision of a Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP), and its broader diplomatic objectives. With the next quadrilateral leader’s summit, to be held in-person in Tokyo tomorrow, it’s worth examining why Japan has so assiduously placed the Quad at the forefront of its regional diplomacy.

Japan initiated the FOIP in 2016 as an unprecedented diplomatic initiative based around three core pillars—rule of law, economic prosperity and peace and stability. The US, and then Australia and India have progressively endorsed this approach and now the FOIP has become codified as the formula around which Quad cooperation has coalesced. The Prime Minister’s Office of Japan (Kantei) has launched a new Quad website in which advertises its mission statement as ‘practical cooperation in various areas, including quality infrastructure, maritime security, counter-terrorism, cyber security, and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, with the aim of realizing a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP)”.’

Uniting its Quad partners around its own vision for the Indo-Pacific must register as a significant success for Japan’s reinvigorated diplomatic agenda. It is also indicative of the greater efforts that Japan is investing in its external relations as part of its avowed ‘proactive contribution to international peace’.

The FOIP encompasses a range of policies and practical agreements that explicitly serve to shape the Indo-Pacific in the direction of a ‘rules-based order’. Such an order, as exemplified to in Quad statements, places emphasis on respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity of all states, freedom from military, economic and political coercion, and promotion of regional stability and economic prosperity. With increasing challenges to this order—ranging from Chinese assertiveness in the East and South China Seas to North Korean nuclear-missile development and Russian aggression in Ukraine—Tokyo (along with its partners) has stressed the need to prevent the region being governed by the axiom of ‘might makes right’.

Two further dimensions to order-building through the Quad on the FOIP model are pertinent. The first is the material balance of power in the region. As China’s strategic weight waxes relative to the US and its allies, bringing India into alignment with the American alliance network—as an individual strategic partner and through the Quad—assists in redressing the shifting power balance in a way favourable to Japan. This is not to suggest that the Quad will be formalised into an ‘Asian NATO’ as its critics claim, but that quadrilateral cooperation does provide a measure of strategic reassurance for Tokyo.

The second is the ideological dimension to Quad cooperation. For Tokyo, uniting four of the region’s most significant democracies is seen as desirable in a world in which democratic liberalism is endangered, human rights are violated and free trade is imperiled. Indeed, Tokyo has long sought to build an ‘Arc of Freedom and Prosperity’ (in 2007, when the Quad first convened) or a ‘Democratic Security Diamond’ (in 2012, upon the return of Shinzo Abe as PM). Upholding such principles, and thus the progressive consolidation of the Quad, tangibly supports Tokyo’s implementation of ‘values-based diplomacy’.

From this, it’s clear why Japanese diplomacy places such a premium on the Quad given the intersections with its own foreign, economic and security policy objectives (as stated in the 2021 diplomatic bluebook). In other words, Japan has much to gain from championship of the Quad.

But in return, Japan has much to offer its Quad partners on the basis of the shared interests and values identified above.

Japan has been undergoing a quiet revolution in terms of its national security strategy over recent years. The combination of domestic security reforms, new security legislation and the restructuring and re-equipping of the Japan Self-Defense Forces makes Japan a far more forward-leaning and capable partner to the other Quad members. The proposed doubling of the Japanese defence budget, if it eventuates, will be a game-changer in Japan’s national security posture.

Thus, all the Quad partners collectively and individually benefit from what Japan brings to the table in terms of achieving common aims. Here, I identify just three ways in which Japan can purposefully contribute to aspects of the Quad agenda.

First, Japan’s economic contribution will be impactful in terms of its technological prowess and its ample official development assistance polices and investment capacities. Japan’s’ existing Partnership for Quality Infrastructure policy is indicative of the contribution it can make to providing the pressing needs for developmental and infrastructure needs in Southeast Asia, the Pacific Islands and beyond (through the Quad Infrastructure Coordination Group). Japan is also well positioned to contribute to the Quad’s mandate for advanced technological collaboration in relation to green technology, clean energy, robotics, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, cyber, space, the electromagnetic spectrum and other emerging defence technologies.

All of this capability will assist in the Quad’s aspirations to establish a ‘secure technology ecosystem’ and to share standards through the Quad Senior Cyber Group, as well as to assist members to collectively keep pace in the unfolding technological competition in the Indo-Pacific.

Reinforcing this, as economic security concerns become increasingly salient in regional strategic competition, Japan’s proven record with regard to multilateral economic institutions and regimes positions it well to contribute to shared Quad objectives in areas such as rules/standards-setting and increased connectivity initiatives. Thus, Japan’s own efforts to deepen cooperation, including economic integration with Southeast Asia, through the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the ASEAN outlook on the Indo-Pacific, reinforce the Quad’s objectives to recognise ‘ASEAN centrality’. The same applies to the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework and Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Japan can also make a significant contribution in the maritime sphere. With impressive naval and coast guard capabilities, it can confidently help deal with issues including law enforcement, maritime domain awareness, partner capacity-building, and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. It is well practised in responding to natural disasters, for example, both domestically and overseas, often in tandem with Quad partners, such as the 2004 core group response to the Boxing Day Tsunami. The Quad discussed HADR for the Ukraine earlier this year. As a maritime nation, Japan can do its part in the Quad shipping taskforce, designed to establish low-to-zero-emission shipping corridors and green and decarbonise the shipping value chain (in coordination with the Quad climate working group).

Recognising that regional challenges cannot be addressed by any country alone, Japan is a keen proponent of Quad cooperation in terms of the national benefits derived from minilateralism and as an active and meaningful contributor to its mandate. Indeed, Tokyo’s sustained championship of minilateral cooperation through the Quad and other mechanisms is testament to the emergent leadership role the country has assumed in regional affairs.

In the same week that Taiwanese took to the streets to repudiate Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Taiwan’s leaders rolled out the red carpet for a visit by former US president Donald Trump’s secretary of state, Mike Pompeo. This is the same man who, together with Trump, withheld military aid from Ukraine to pressure its government to initiate a bogus investigation into US President Joe Biden’s son, and who then fired the US ambassador to Ukraine when she refused to cooperate.

The jarring juxtaposition of these two events—the Taiwanese people supporting a fellow democracy while their leaders lavished praise on the man who undermined that democracy’s security—reflects a reckless willingness to embrace any foreign politician who will ‘stand with Taiwan’. Taiwanese leaders are focused so intently on gaining international recognition that they ignore the key threat Taiwan faces: an invasion by China similar to what Russia has done in Ukraine.

Taiwan’s development over the past few decades has been truly miraculous, even in a region with some of the most successful countries in the world. Within the span of a generation, Taiwan has grown from a poor, primarily agrarian society with an authoritarian regime into a vibrant democracy boasting some of the world’s most important companies, such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, or TSMC. Even more remarkably, this transformation occurred in the absence of formal diplomatic ties or participation in international organisations such as the United Nations.

But Taiwan has continued to push for formal diplomatic recognition and participation in international forums. If that requires embracing figures like Pompeo—who used his latest visit to declare that the United States should extend formal diplomatic recognition to Taiwan—so be it.

Taiwan’s poor choice of friends is not limited to American politicians. When multilateral lenders cut off Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega’s corrupt regime following its brutal crackdown on protesters in 2018, Taiwan stepped in with a US$100 million loan to the dictator. And in November, Taiwan hosted then-Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernández, even though it was widely known that he was involved in drug trafficking (in March, he was indicted on federal drug charges in the US). Both Nicaragua and Honduras belong to the small minority of UN member states that formally recognise Taiwan as a sovereign country.

Obviously, Taiwan cannot be both a beacon of democracy and a financier of ‘white terror’ operations in other countries. It cannot claim to stand with the world’s democracies if it is also going out of its way to support US politicians who have threatened and undermined democratic regimes both abroad and at home. Such behaviour not only betrays the democratic ideals that Taiwan stands for, it also ignores the threat that Taiwan faces from China.

That threat outweighs all others. The central goal of Taiwan’s foreign policy, therefore, should be to deter China from pursuing the kind of reckless aggression that Russian President Vladimir Putin has launched in Ukraine.

For Taiwan, effective deterrence has two components. First, China must be made to understand that it would pay a high price—militarily, economically and diplomatically—were it to invade. Taiwan and the rest of the world’s democracies must make it absolutely clear that the day China invades Taiwan would also be the day it gives up on Deng Xiaoping’s program of ‘reform and opening up’. Second, Taiwan must avoid actions that would put Chinese leaders in what they would claim is an impossible situation. Specifically, it must not formally declare its independence or seek to secure membership in the UN.

Deterrence has been effective so far, but it now faces two major challenges. First, America’s own strategic disengagement from China may eventually lead Chinese leaders to conclude that they have little to lose—at least in terms of China’s ties to the rest of the world—by trying to take Taiwan by force. Although there’s not much that Taiwan can do about the battle between the two superpowers, it should think twice before embracing US politicians whose only interest in Taiwan is to use it as a cudgel against China.

The second challenge comes from Taiwan’s push for formal recognition. A critical part of deterrence is to avoid actions that would give China an excuse to attack. UN membership or formal diplomatic recognition by the US would be viewed as a step on the path to formal Taiwanese independence. That could force China’s hand, because no Chinese leader could survive if he did nothing in response to such a step.

Pompeo’s statement of support for formal diplomatic ties between the US and Taiwan is thus extremely reckless, as is the Taiwan leadership’s decision to give him a platform to disseminate that message. The strong ties between Taiwan and the US would not be made any stronger if Taiwan’s representative office in Washington DC were to become an embassy. On the contrary, formal diplomatic recognition would leave China no choice but to sever ties with the US, an outcome that would ultimately endanger Taiwan.

Taiwan’s most important international relationships are with Japan and the US, neither of which has formal diplomatic ties with the island. The strength of these relationships is rooted in trade, business ties and millions of people-to-people exchanges. These are what matter—not UN speeches or 21-gun salutes during state visits. Taiwan must not confuse the trappings of nationhood with the reality of nationhood. It should focus on strengthening a status quo that has enabled it to prosper, and it should politely decline future overtures from craven opportunists and authoritarians.

The Australian and Japanese prime ministers met virtually on 6 January and signed a reciprocal access agreement (RAA) that makes it easier for each nation’s troops to operate in each other’s country. As important, it strengthens the political and psychological groundwork for increased military cooperation between the two nations.

It’s the first such agreement Japan has signed with a country besides the United States. And it took a while.

An agreement in principle was reached in November 2020 between Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga and Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison—after six years of negotiating. It took another 14 months to finalise the deal.

The door is now open wide in both directions for practically any initiative the two sides desire.

One should remember, however, that the Japanese and Australian militaries are not strangers. Japanese forces have been training in Australia since the early 2010s, which included sending ships and troops to Talisman Sabre and other exercises. Japanese ships have also exercised alongside the Royal Australian Navy in the Indian Ocean Malabar Exercise and in the South China Sea.

Individual Australian Defence Force personnel have been assigned to Japan for decades. And Royal Australian Air Force aircraft have used US bases in Japan (under United Nations auspices) in recent years while enforcing North Korea sanctions. And in September 2019, a detachment of Australian F-18s conducted the first-ever joint combat exercise with the Japan Air Self-Defense Force in Japan.

A decade ago, most observers considered a Japan–Australia RAA and all the above activities to be impossible.

Chinese threats, pressure and sabre-rattling do indeed have a silver lining.

Now that the deal has been signed, the important thing is what both sides make of it.

There are some easy things to start moving forward with.

An Australian Army liaison officer is now assigned to the Japanese Ground Self-Defense Force’s Ground Combat Command in Japan. But that’s not so useful. It will be better to see an Australian liaison officer or two assigned to the Japan Self-Defense Forces headquarters in Tokyo.

The right officers, doing some pushing and persuading—and with some help from the US Marines and US Navy—can move the Australia–Japan defence relationship forward on a far broader front than just army to army.

And when the Americans and Japanese finally establish a joint headquarters in Japan (hopefully before hell has frozen over), the Australians should be an integral part of it.

Another helpful initiative would be sending a RAAF squadron to Japan on long-term deployment and, vice versa, a Japan Air Self-Defense Force squadron to Australia. Bringing the Australian army and navy to exercise in Japan is also easy.

Besides the favourable optics of the JSDF and ADF operating together, Japan benefits from deeper exposure to another military and different ways of doing things. And both benefit from the psychological and political ties that come from deeper military-to-military relations.

The JSDF needs opportunities for realistic training to better professionalise itself. It can’t do this in Japan, owing to limited training areas and excessive local restrictions.

Australia offers excellent opportunities for all three JSDF services to train by themselves, together and with other militaries.

Australia’s Northern Territory, in particular, is the best place in the entire hemisphere for the sort of unrestrained, combined arms training that Japan desperately needs. The JSDF’s only alternative is to make the trip to Southern California—and even then, US training facilities are not as good as those in the Northern Territory.

Here’s one idea: combine Japanese and Australian amphibious forces into a joint task force to master the complex air–sea–ground coordination that is part and parcel of amphibious operations—but also applicable to a broader range of military operations.

Send a Japanese amphibious ship—even an older tank landing ship—and a battalion of Japanese ‘marines’ from the Amphibious Rapid Deployment Brigade down to Australia for six months and operate out of Darwin, as well as over in Queensland, with Australia’s amphibious force. It’s a good way to give the new unit some real experience outside Japan, in an unfamiliar environment and with foreign forces. That’s how a military improves. Australia’s amphibious force can also use the practice.

Maybe the two could operate the Australian–Japanese task force up into Southeast Asia or throughout Oceania, with training in humanitarian assistance and disaster response as one of its missions. That’s urgently needed as Chinese influence steadily expands in the region.

This is all far preferable to the canned exercises in Kyushu or Hokkaido—with ‘commissars’ at JSDF headquarters in Ichigaya nearby to keep the training as ‘safe’ (in other words, unrealistic) as possible—while cowering in fear that somebody might complain the training is ‘too noisy’ or ‘scary’.

But isn’t the Talisman Sabre exercise enough? Maybe just make it bigger?

No. Talisman Sabre is a good exercise. But for the participants, such exercises can become like a piano player who practises only one song. They might play it perfectly, but it’s still just one song. Moreover, it’s a song opponents have had time to study.

The RAA is politically important. Rather than giving in to Beijing’s threats and bullying, two of Asia’s key democracies are deepening their defence ties—with the potential for creating real operational capabilities—and employing them around the region.

The RAA also belies Beijing’s shrill claims that regional nations dislike Japan because of World War II and fear a remilitarised Japan. The Australians have as much reason as anyone to hold a grudge, but they’ve long since recognised that today’s Japan isn’t 1930s or 1940s Japan. Take away Korea and China, and that’s the feeling throughout most of the Indo-Pacific, if one looks closely.

The RAA is also good news for the Americans.

For starters, US forces are overstretched regionally and worldwide. Whatever the JSDF does in or with Australia feeds into the United States’ desperate (though unstated) need for a more capable JSDF. That means a JSDF capable of fighting in its own right, and also as an ally. And this is no less beneficial to Australia—which is game, but not big enough to defend itself against an angry China.

As important, increased Japan–Australia activities break down the hub-and-spoke nature of the US presence in the Pacific. That’s a construct that has American forces operating too often bilaterally with Asia–Pacific nations (the ‘spokes’).

The spokes need to operate together—creating a more durable web—without the Americans driving things. Doing so improves capabilities and also deepens the psychological and political ties that come from military-to-military engagements between like-minded nations.

This doesn’t mean the Americans are excluded or unnecessary, but rather it bolsters the US presence as part of a more complex and stronger web of defence relationships. It should be seen as cross-bracing rather than as a replacement or a hedge.

The web approach is particularly important because, given that the countries involved are democracies where policies can change with elections, the more there are overlapping defence relationships, the more likely the region as a whole can continue to build its defence posture even if the government changes in one of the partners.

Beijing is of course displeased with the RAA and will use its levers to try to stifle it before it can fully form.

Japan’s once powerful pro-Beijing constituencies in the political, official and business worlds are quiescent for now, but that can change. Given this, one wonders if Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s administration might put a brake on attempts to do more with Australia on the military front.

Something similar may even play out in Australia should the Labor Party win the next election. Laborites say they won’t, but one wonders.

Also, hopefully, the Japanese government doesn’t see the RAA as meaning Japan needs to do less defence-wise.

Kishida needs to allow the JSDF to up its game considerably. Japan’s military still needs more money (for training and personnel) and to meet recruiting targets that it has missed by 25% annually for years. The JSDF is still not ready to fight a war—needing, among other things, a joint capability (which it doesn’t have).

Too often it seems that signing an agreement is an end in itself.

So here’s an idea. A year from now, let’s hold another press conference and see what has actually been accomplished out of the RAA—and what the Japanese and the Australians are doing with each other—that could only have happened because of the RAA.

Sometimes it’s good to keep score.

Australia may have a way of very cheaply and quickly expanding its submarine force, improving its defences this decade and preparing for its planned nuclear-powered boats.

We might do this by buying good second-hand submarines from Japan. The possibility would present some problems and could in fact be unworkable, but it offers such great potential advantages that we must look hard at whether it could be achieved.

It should not be summarily dismissed as unconventional and managerially complicated.

Australia’s first nuclear submarine won’t be ready until about 2040 if it’s built in Adelaide. By importing nuclear boats, that might be brought forward to 2031 or even 2030. But that would still leave the submarine force at its current, inadequate level in the 2020s, which are looking increasingly dangerous.

We’ll also have the challenge of generating crews for the nuclear submarines, whenever they appear. The more submarines in service, even if they are diesel powered, the easier it will be to create crews.

One proposal that would address the training problem has been to buy new diesel submarines as stopgaps, ideally using a design based on the current Collins class.

This solution has three serious drawbacks. Even Collins derivatives probably couldn’t be delivered until the 2030s. Construction would be expensive and, for a small batch, highly uneconomical. And Australia would end up stuck with new submarines with a form of propulsion that it already regards as inadequate for the long term.

Second-hand Japanese submarines, by contrast, might be acquired very quickly and cheaply, and, having perhaps seven years of life left in them, wouldn’t hang around as doubtful assets into the 2060s.

The Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force takes delivery of one submarine a year. For any other navy, that would imply a fleet of about 30 boats, since a submarine can typically serve for something like 30 years. But the force is not funded to operate so many and instead retires them early.

Until a few years ago, the fleet comprised 18 submarines. The number is now 23 and soon due to rise to 24, including two training boats.

The submarines we might lay our hands on are contemporaries of the Collins class, the Oyashio class, commissioned between 1998 and 2008.

Their surface displacement is 2,800 tonnes, compared with 3,100 tonnes for the Collins class. Their endurance and range are probably adequate for Australian missions. Their silencing and sensor performance are unlikely to be second-rate, but their crew size is largish at 70.

Oyashios in Australian service would be used closer to home than the long-range Collins class. They could cover the archipelagic straits of the approaches to our continent and help deal with targets that got through. All Collins boats would then be available for more distant missions.

Japan has already demoted the two oldest Oyashios to training roles, modifying them accordingly. Nine more remain in frontline service, still with full combat capability and each seemingly destined for retirement at age 23.

These include seven confirmed in 2018 as refitted to give them longer lives than originally planned and to bring them to almost the technology standard of the later Soryu class, itself once a candidate to replace the Collins boats. The other two front-line Oyashios have presumably been similarly refitted since then.

Since Japan’s submarine fleet still needs to expand by one, we should assume the country won’t decommission an Oyashio in 2022 as it takes delivery of a new vessel. Instead, the oldest frontline boat of the class, the Uzushio, may become available in 2023.

Australia could ask Japan for the Uzushio and the other eight frontline Oyashios as they leave service at yearly intervals. The purchase price shouldn’t be much above scrap value.

Japan would be delighted by the closer defence relationship, and it would get business in supporting the vessels.

Many countries operate high-quality second-hand warships, often bought from the US or UK. Australia has done so many times, and it has lately sold two capable upgraded frigates to Chile.

The Australian collection of Oyashio-class boats would reach seven in 2029 and remain at that level until 2031, assuming, roughly, that their age limit is 30. After that period, the number would decline by one a year—conveniently in step with a feasible schedule for arrival of imported nuclear boats. One in, one out.

Notice that with this proposal Australia could have 13 diesel submarines in service 25 years earlier than it was planning to have 12 under the cancelled Attack-class contract.

Mission availability of second-hand Oyashios might be better than that of the Collins class, because they would never go into the two-year major refits the Collins boats will undertake.

Supporting a completely unique class of vessels might look like an unattractive proposition, but it wouldn’t be impossible: the Collins-class boats are similarly full of systems and weapons not found elsewhere in the navy.

The support problem could be enormously reduced by relying as far as possible on Japan’s mature maintenance establishment for these submarines. Whenever necessary, they would be sent back to Japan for work. Keeping them in the hands of engineers and technicians who have long familiarity with them would greatly improve our confidence in prolonged operation.

Doing so should also be highly economical. Australia wouldn’t pay for plant and training to create elaborate domestic support infrastructure. For minor maintenance, Japanese shipbuilders and system suppliers could help by stationing people in Australia.

Japan would surely be a reliable partner for Australia in this. The two countries have the same strategic problem: China.

The big unknown in this proposal is how hard it would be to keep the Japanese submarines serving beyond 23 years.

Their physical condition upon retirement from the Japanese navy shouldn’t be a problem. Consider the Japanese reputation for excellent production and maintenance of physical articles. In 2016 then-ambassador Sumio Kusaka wrote that, by applying the Japanese maintenance routine, Australia could operate Soryu-class submarines for ‘a long period of time’.

Still, the Oyashios’ current maintenance timetable is presumably phased so that each submarine is due for more work at the point of retirement. Each boat might therefore need a routine refit before commissioning into the Royal Australian Navy.

The potential showstopper is whether old electronics and software could be supported to age 30. That would depend in part on the depth of the modernisation the boats have had. Problems in this respect might be addressed with a little more updating, the cost of which should still make these submarines a bargain.

To get started with operations, we could ask Japan to lend a complete crew. Needing adequate English, these people would train Australians and gradually go home as the locals became familiar with how to operate the boats. Since the Japanese navy has so many submarines, it should be able to conjure up one more crew without too much difficulty.

Manuals would have to be translated to English, but display text of electronic systems would not, since such fiddling would be an unnecessary complication.

The idea of Australian sailors looking at, for example, combat-system menus written in Japanese may seem challenging, but members of armed services all over the world have to learn enough English to operate imported equipment. There’s no reason why Australian sailors shouldn’t be able to learn a little Japanese.

With Oyashios arriving annually from 2023, time available for training would be short. But the delivery timeframe is so attractively quick that slowish achievement of operational capability would be acceptable.

The government should urgently examine this possibility. And it should insist that the navy and Department of Defence look not just for problems in operating second-hand Japanese submarines but also for solutions.

Ninety years ago, on 18 September 1931, a junior Japanese military officer detonated an explosive that had been carefully laid by a Japanese-owned railroad near the northeastern Chinese city of Shenyang (then known in the West as Mukden). The blast did little damage, but that wasn’t the point. The Japanese blamed Chinese soldiers for the explosion, which they used as a pretext to capture Shenyang and occupy the entire territory, known as Manchuria.

Though Manchuria was a Chinese territory, controlled by warlords loyal (in name if not in reality) to China’s nationalist government, thousands of Japanese soldiers were stationed there under the terms of an earlier treaty. This enabled Japanese forces to overrun the area quickly. Within weeks of the Manchurian Incident, they controlled the southern part of Manchuria, with the north following by early 1932.

This was no imperial invasion, the Japanese claimed. Rather, it was a response to the cries for help coming from the people of Manchuria, who were suffering under the warlords’ iron-fisted rule. Japan merely wanted to help oppressed people to establish an independent state that would liberate them from the maelstrom of corruption that enveloped the rest of China.

Japan even had a name for this new state: Manchukuo, or ‘land of the Manchus’. To add lustre to their vision, they recruited the most famous Manchu around—China’s last emperor, Puyi—to lead it. (Having been deposed in 1912, Puyi was available for alternative monarchical engagements.)

The effort to create an independent Manchurian state became an international cause célèbre, and a test for the League of Nations, the precursor to the United Nations tasked with preserving peace after World War I. The League sent a commission, led by British diplomat Lord Lytton, to investigate the situation. The commission concluded that Japan had effectively staged a coup.

Japan was undeterred. It withdrew from the League of Nations, and held onto its Manchurian puppet state until its defeat in World War II. At that point, the Soviet Union took over, occupying the territory for a year.

At the same time, however, the long-running war between the Chinese Nationalists and Communists was heating up again, with Mao Zedong’s forces claiming more and more territory, beginning in the northeast. By the time the Communists established the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the Manchurian provinces were firmly within their grasp.

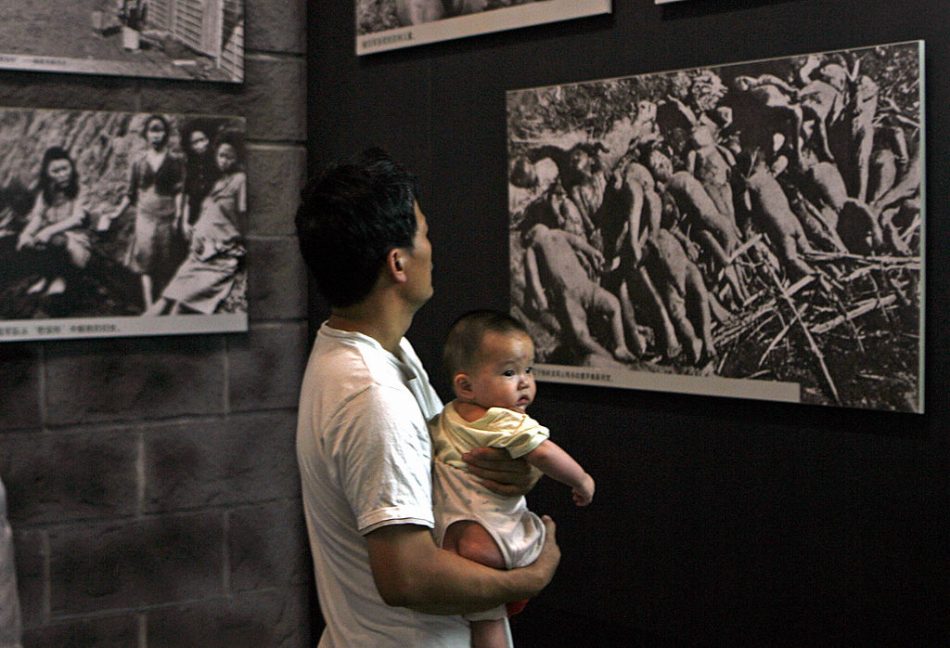

But the Chinese have not forgotten the 14-year occupation of Manchuria. In fact, official Chinese doctrine establishes the 1931 Manchurian Incident as the beginning of World War II. And every year on 18 September sirens wail in Shenyang and other cities in the region to commemorate not just the explosion itself but the atrocities that followed. These include the horrific experiments that Unit 731—the Japanese army’s research-and-development unit for biological and chemical warfare—carried out on live subjects.

What do these memories mean today? Within China, the message is clear: before the People’s Republic was established, the country was weak and vulnerable to foreign invasion. A major museum in Shenyang, which tells the story of those who died fighting the Japanese occupation, reinforces the narrative that China’s Nationalist leaders did little to protect the country from humiliation by invaders.

But while China’s leaders are eager to use the Manchurian Incident to advance their favoured narrative of the past, they hesitate to acknowledge echoes of the event in the present, particularly when it comes to the actions of China’s close military and strategic partner, Russia. In 2008, when Russia invaded Georgia, Chinese leaders, perhaps quietly seething over the distraction from the start of that year’s Olympic Games in Beijing, refrained from voicing strong support for its actions (unlike other Kremlin allies such as Belarus). But they didn’t push back either, merely calling for all sides to remain calm.

Likewise, in 2014, China refused to denounce Russia’s occupation and annexation of Crimea from Ukraine, or the Kremlin-organised plebiscite, unmonitored by any neutral body, that endorsed it. When the UN Security Council considered a resolution condemning the referendum, China abstained.

Of course, China itself has been known to redefine territorial questions to its own benefit. But, unlike Russia, China has avoided brazenly crossing internationally recognised borders. Yes, it has pushed hard at boundaries in the Himalayas and the South China Sea. But it has reserved its harshest aggression for areas clearly within its territory, such as Hong Kong and the Xinjiang region, and its strongest threats for the one place, Taiwan, where the Cold War left some level of ambiguity.

This is another legacy of the Manchurian Incident. The direct violation of an international land border remains an uncomfortable prospect for the Chinese.

China’s remembrance of the Manchurian Incident raises one more question: how do its current leaders believe the international community should have responded? In general, they take the position that disputes should be settled through dialogue and negotiation, rather than military action. They pour scorn on American interventions, such as in Afghanistan. Given this, it’s harder for China’s leaders to argue that, after the League of Nations’ attempts to dissuade Japan failed, the international community should have taken stronger military action in 1931.

To be sure, America’s interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq had their own dynamics; they were by no means repeats of the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. But it’s striking that, for China, the Manchurian crisis of 1931 remains such an important cause for national remembrance but doesn’t yield easy lessons for reflection, let alone obvious analogies for dealing with today’s geopolitical challenges.

Japan’s new defence white paper, Defense of Japan 2021, affirms Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga’s continuation of his predecessor Shinzo Abe’s proactive contribution to regional peace and security.

Stemming from a desire to counter any trend towards a norm of ‘might is right’ in the region, the white paper must be seen in the context of broader diplomatic efforts by Japan to champion a rules-based order. This is exemplified by its vision for a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’, first introduced in 2016, which has three ‘pillars’: rule of law, economic prosperity, and peace and stability. The 2021 white paper is designed to support each of these objectives.

The new white paper has been warmly received by allies and partners in Washington and Canberra, but has drawn predictable denunciation from Beijing, particularly for its stance on Taiwan and the explicit statement that ‘Taiwan is important for Japan’s security and the stability of the international community’. Xi Jinping’s reiteration of his desire to achieve ‘national reunification’ in his speech at the centenary celebrations of the Chinese Communist Party, along with the US Indo-Pacific Command’s warning that a conflict could break out within the next six years, have alarmed Japanese policymakers.

Noting the shifting military balance in the Taiwan Strait, as well as in the region as a whole, in China’s favour, the white paper states that Japan must ‘pay close attention to the situation with a sense of crisis more than ever before’.

Though Japan has maintained warm, if low-key, relations with Taipei, it has traditionally eschewed overt support for the beleaguered island democracy. The 2021 white paper signals a significant policy change. This comes on top of slightly overwrought comments by Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso, a long-time supporter of Taiwan, who said that ‘Japan and the US must defend Taiwan together’ if China mounts an invasion of the island. The remarks were later retracted, and both Tokyo and Washington recited their pro forma commitments to the ‘One China’ principle. Nevertheless, it’s clear that the mood in Tokyo, as in Washington, has shifted towards increased support for Taipei, not least because of the sympathies of some of Japan’s policymakers in Japan at present, including not only Aso but also Defence Minister Nobuo Kishi.

The white paper also addresses the related issue of Chinese assertiveness towards Japan directly, backed by ever-expanding military power. Japan bears the brunt of this in the East China Sea in the waters around the Senkaku Islands (claimed by China as the Diaoyudao (and Taiwan as the Diaoyutai)). The document notes that ‘China has relentlessly continued attempts to unilaterally change the status quo by coercion in the sea area around the Senkaku Islands, leading to a grave matter of concern’. Typical of the grey-zone tactics brought to bear in this maritime space are the incessant incursions of China Coast Guard vessels into territorial waters. The white paper expresses consternation at China’s recent coastguard law, which it claims is inconsistent with international law, especially in the authorised use of weapons.

The white paper discusses a range of other ongoing security concerns, with North Korea’s continued nuclear bellicosity salient among them, but also touches on environmental challenges and the response to natural disasters.

But it is more than mere talk. To support Japan’s more proactive role in regional diplomacy and security, the white paper showcases recent developments in Japanese defence technology, especially in the new domains of space, cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum. This is backed by defence budget increases for nine years running.

Japan has invested in defence collaboration with other countries for the development of game-changing military technologies, such as artificial intelligence, hypersonic weapons, quantum technology and 5G. Notably, the white paper highlights the development of standoff missile as a strike capability, often described as the ‘Japanese Tomahawk’. Yet, it’s important to stress that in accordance with domestic and international legal frameworks they can’t be used for a pre-emptive strike.

The white paper also recognises that regional security challenges ‘cannot be dealt with by a single country alone’. In addition to a significant effort to better mobilise its defence capabilities and diplomatic strengths, key to Japan’s regional posture is the support of other significant players in the region. The longstanding alliance with the US, which Japan is actively strengthening, provides a major fillip, due not only to the military power and influence it carries, but also to the diplomatic support that the US has afforded to Tokyo through its own adoption of the principle of a free and open Indo-Pacific.

Australia, too, has been a de facto supporter of this principle, and Canberra’s ‘special strategic partnership’ with Tokyo continues to be augmented. The Japanese ambassador to Australia, Shingo Yamagami, recently made overtures to Canberra about engaging Australian support for Japan’s predicament in the East China Sea. India is another country that Japan looks to in its bid to uphold the regional order, and the partnering process is brought together in the alignment of the four countries through the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue.

Criticism of the new white paper has been quick to emerge, with Beijing diplomatic and media outlets seizing on the Taiwan statements. Criticism has also extended to the presentation of the document, particularly the decision to put a ‘warlike’ image of an equestrian samurai on the cover, perhaps in a bid to resurrect perceptions of Japan’s prior militarism.

Nevertheless, as a response to the intensifying strategic competition in the region and Japan’s perception that its security environment is further deteriorating, the white paper provides firm evidence of the Suga administration’s determination to uphold national interests and the regional rules-based order through a combination of proactive diplomacy, internal mobilisation and enhanced collaboration with allies and partners.

The 11th of March 2021 marks the 10th anniversary of the earthquake and tsunami that devastated northeastern Japan, killing more than 16,000 people and leading to the Fukushima nuclear accident. On hearing of the disaster, Australia’s well-practised and disciplined crisis-response mechanism swung into action. The government decided to send an urban search and rescue, or USAR, team, which was to fly to Japan on a Royal Australian Air Force C-17 heavy transport aircraft.

In Japan, unsurprisingly, there was a great deal of confusion. The devastation was widespread, communication systems were down and the government was mobilising national resources to respond to the catastrophic event. The Japanese were also attempting to coordinate the many offers of assistance they had received from around the world, all the while enduring multiple aftershocks. In the 24 hours following the initial quake, more than 70 aftershocks above magnitude 5.0 were recorded.

Australia was fortunate that a year earlier a RAAF group captain had been sent to Yokota Air Base, a US facility in western Tokyo, and appointed to head United Nations Command–Rear, a small unit responsible for supporting international forces should they need to respond to a crisis on the Korean peninsula.

Despite having no role or authority to do so, UNC–Rear accepted responsibility for managing the arrival of the C-17 and the USAR personnel. Being co-located with US Forces Japan enabled UNC–Rear to coordinate with the Australian embassy and liaise directly with American and Japanese officials to guarantee the entry of the C-17 and the USAR team. In addition, the New Zealand embassy contacted UNC–Rear and requested that it support a small New Zealand USAR team, arriving on a commercial flight, that would marry up with the Australian contingent. This task was also accepted.

The delivery of the USAR team could have been the completion of the mission for the RAAF, but Chief of Air Force Mark Binskin approved the C-17 to remain in Japan if it could be employed to support relief operations. Following a short conversation with the US Air Force colonel responsible, arrangements were made for the RAAF aircraft to integrate into the USAF relief effort, with UNC–Rear providing coordination and support.

The C-17 remained in Japan for two weeks and flew 23 sorties, ranging from Okinawa in the south, to airfields north of the disaster area, and to Sendai, in the disaster area itself. It carried more than 450 tonnes of crucial relief supplies as diverse as water, baby formula, nappies and food. It also carried Japanese military vehicles and 135 personnel to support the relief efforts.

The Fukushima nuclear disaster added a further level of complexity to relief efforts. For RAAF personnel in Japan, it meant operating in an uncertain environment where understanding and managing risk became hugely important. No one had operated in a potentially radiologically ‘hot’ environment before, so techniques and procedures had to be rapidly developed.

The nuclear accident also added another layer to Australia’s response. Keeping the Fukushima reactors cool to prevent a meltdown was a major focus of the Japanese authorities and more pumps to keep them doused with water were required. US engineering firm Bechtel offered to supply an unmanned water cannon, which was located in Perth, and the US sent a request through UNC–Rear asking whether the RAAF could transport it to Japan.

The RAAF response was swift. The two available C-17s were diverted from their planned tasking to RAAF Base Pearce near Perth and an air load team worked day and night to develop the structures and supports needed to load the pumping equipment and pipes onto the aircraft—a task that had never been done before. As soon as they were able, the C-17s left Australia for Japan and delivered their cargo. They remained in Japan for a few days before departing and were soon followed home by the original C-17 with the USAR team on board.

Among all of the nations that supported the relief effort, the Australian contribution stood out. Australia was the only nation aside from the US that made a direct contribution of military forces, and the RAAF integrated seamlessly with its US and Japanese counterparts.

Why did it work so well? First, there was a determination by all the Australians involved that they were going to assist and wouldn’t take no for an answer. Second, military-to-military relationships are built on two pillars: the structural, which comes from agreements, memorandums of understanding and so on, and the personal, which comes down to trust. The RAAF had been investing in its relationships with the US and Japanese air forces for many years and had built both the structural and trust frameworks needed to get the job done.

While the RAAF had worked with the Japan Air Self-Defense Force before, it had not carried any Japan Ground Self-Defense Force equipment—but the USAF had in its C-17s. Tripartite sharing of information, common standards and high levels of trust meant the RAAF could move Japanese forces without any undue concerns on anyone’s part.

Australia had a choice; it did not have to respond in the wake of the earthquake and tsunami, and when it did the contribution of the USAR team would have sufficed. It must be remembered that in 2011 the RAAF operated only four C-17s (it now has eight). In the middle of the crisis, three were deployed to Japan and the fourth was in Australia undergoing heavy maintenance and couldn’t fly. To commit Australia’s entire available C-17 fleet came with a level of risk, but also demonstrated a significant level of commitment, and the contribution they made in a short period of time was invaluable. Japan noticed what Australia did.

The RAAF personnel understood how to work with their US and Japanese counterparts, they acted whether it was in their job description or not, and they accepted responsibility for the task. By integrating an Australian air component in the middle of a triple disaster and operating in uncertain conditions, they demonstrated agility, flexibility, professionalism and compassion.

In the aftermath of the disaster, the majority of the accolades and formal honours went to Australian embassy staff in Tokyo, and the contribution of the RAAF and UNC–Rear was largely overlooked. Yet, arguably, the air force contribution, enabled by the UNC–Rear staff, was the defining factor that demonstrated to Japan that Australia was not only a committed friend, but also a highly competent security partner—and that view has set the tone of the relationship ever since.

Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, although something of an unknown quantity prior to his appointment, is already showing promising signs of stepping into the foreign policy breach left by his predecessor, Shinzo Abe.

Some international commentators have been overly quick to dismiss Suga as a cipher. Indeed, he comes from the same Liberal Democratic Party as Abe, his cabinet remains largely unchanged and he consistently demonstrated loyalty to the former prime minister. Yet the changes he has already initiated suggest that, in addition to maintaining Abe’s robust determination to bolster Japan’s place in international security issues, Suga is his own leader, with his own agenda. Importantly, Suga looks set to make some significant changes to Japan’s cybersecurity policies.

China’s continuing grey-zone aggression in the Indo-Pacific and the lingering uncertainties about the US’s commitments to the region mean that Japan’s approach to regional security is becoming more important than ever. There are already signs that Suga understands this. His vocal role in Quad talks with the US, India and Australia, along with his invitations to other foreign leaders, are strong indicators that he intends for Japan to continue to play a key role in Indo-Pacific security. The four countries’ foreign ministers held talks on 18 February which placed an emphasis on ‘advancing practical cooperation in various areas towards the realization of a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific”.’ Cybersecurity was identified as a key area for collaboration.

China’s political warfare methods heavily emphasise coercion through cyber and information operations, so the time is ripe for Japan to forge ahead with cyber cooperation with allies and partners in the region—and it seems Suga is well aware of this. In August, just a month before he became prime minister, he observed on the margins of a multilateral cybersecurity exercise organised by Japan: ‘It is very important that malicious cyberattacks are promptly detected and acted upon, minimizing spread of the damage … We cannot act fast and appropriately without close cooperation with other countries.’

In addition to maintaining continuity with the security narrative initiated under Abe, multilateral collaboration on cyber defence has rich potential to bolster Japan’s credentials as a credible and committed regional player.

As Japan’s security position has, if anything, worsened since Abe’s departure, Suga likely views cybersecurity cooperation as one way to counter these challenges. In a region increasingly characterised by competition, coercive statecraft, economic warfare and active disinformation operations, cybersecurity will continue to be a pivotal issue.

But to date, Japan’s obsolescent domestic cybersecurity apparatus seems to have been of only dubious merit and effectiveness. Japan’s primary cyber capability, the Cabinet Secretariat’s National Center of Incident Readiness and Strategy for Cybersecurity, or NISC, has mostly failed at keeping Japan cyber secure. One reason for this is that the centre was designed only to improve the cybersecurity of government agencies. This overly narrow focus not only fails to protect citizens from cybercrime, but also leaves gaping vulnerabilities for the government itself. Government agencies can be targeted through non-government angles. Supply chains, subcontracting and collaboration between private and government sectors all lie beyond the scope of the NISC.

To address these weaknesses, Suga will need enact large-scale reforms. Equipping Japan with a modern and effective cyber capability will be a major administrative undertaking.

Reform on such a scale has traditionally proven difficult in Japan, and the Covid-19 pandemic has been a rude awakening for Japan on how far behind it is in the adoption of digital technologies. Hospital staff still sign and send papers physically or through fax, a practice that has significantly hindered the government’s response to emerging coronavirus clusters. And the failure to effectively deal with the mass movement of people to remote work has further revealed Japan’s unpreparedness to manage contemporary digital requirements.

But if Covid-19 has shown the rust in Japan’s system, Suga is trying to push the gears of change. One of his first actions as prime minister was to call for the creation of a new agency to assist in Japan’s ‘digitisation’. He also created a new ministerial position and assigned highly popular former defence minister Taro Kono as administrative and regulatory reform minister. Kono is now also responsible for Japan’s Covid-19 vaccine rollout.

Suga’s early actions indicate a promising level of commitment to addressing Japan’s digital problems. His greater focus on multilateralism will strengthen Tokyo’s international relations and strategic position. Digitisation and widespread administrative reform also seem to be high on his list of security initiatives. Such actions will be vital if Japan’s regional security ambitions are to be realised.