Geopolitics, influence and crime in the Pacific islands

Getting caught up in geopolitical competition may seem uncomfortable enough for Pacific island countries. What’s making things worse is that outside powers’ struggle to influence them is weakening their resistance to organised crime emanating from China.

Getting caught up in geopolitical competition may seem uncomfortable enough for Pacific island countries. What’s making things worse is that outside powers’ struggle to influence them is weakening their resistance to organised crime emanating from China.

And that comes on top of criminal activity that’s moved into Pacific islands from elsewhere, including Australia, Mexico, Malaysia and New Zealand.

This situation must change if peace and stability are to be maintained and development goals achieved across the region.

The good news is that, Papua New Guinea excluded, Pacific island countries have some of the lowest levels of criminality in the world. The bad news is that the data suggests the effect of organised crime is increasing across all three Pacific-island subregions—Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia.

The picture is worst in Melanesia and Polynesia, where resilience to crime has declined. In many cases, Pacific Island countries are insufficiently prepared to withstand growing criminal threats, exposing vulnerable populations to new risks.

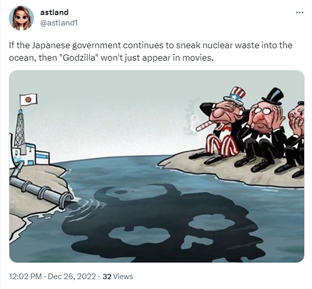

As China has gained influence in these countries, its criminals and criminal organisations have moved in alongside honest Chinese investors. Some of those criminals, while attending to their own business, are also doing the bidding of the Chinese government.

If the criminal activity involves suborning local authorities—and it often will—then so much the better for Beijing, which will enjoy the officials’ new-found reliance on Chinese friends that it can influence.

Democracies competing with China for influence, such as the US, Japan and Australia, are unwilling to lose the favour of those same officials. So, they refrain from pressuring them into tackling organised crime and corruption head on. The result is more crime and weaker policing.

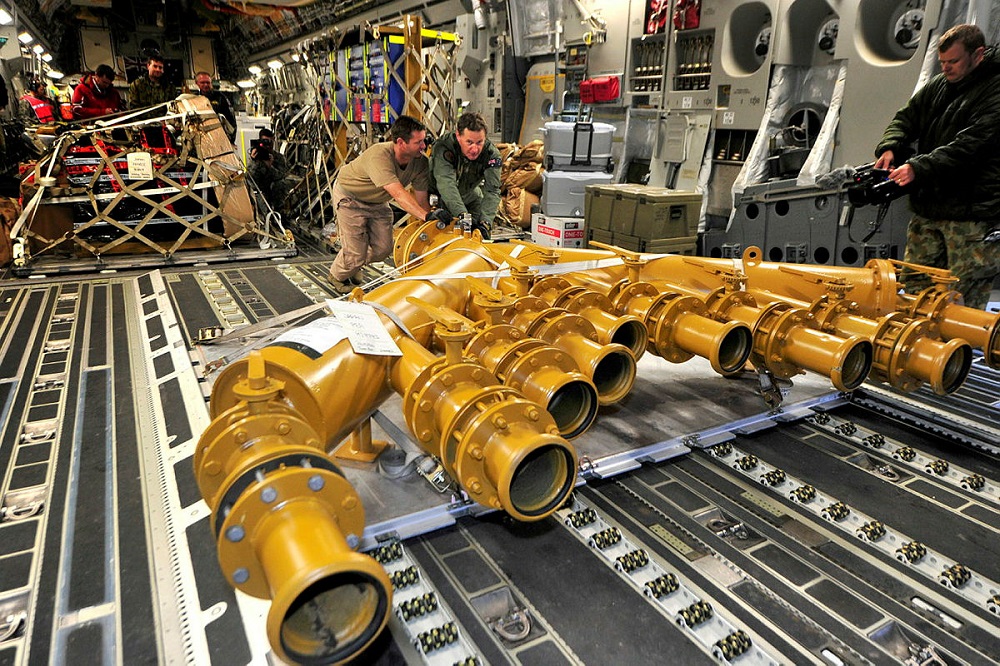

But more factors are at play here. Growing air travel and internet penetration have helped turn the islands into more accessible destinations and better-integrated points along global supply chains of licit and illicit commodities.

When one starts mapping who is behind major organised criminality, the protagonists are almost always foreigners. The islands do have home-grown gangs but, when there is a lot of money to be made, there is usually the involvement of a Chinese triad, a Mexican cartel, a law-defying Malaysian logging company, or some similar criminal organisation.

Groups that have entered the islands, such as Australia’s Rebels and New Zealand’s Head Hunters, both outlaw motorcycle gangs, or the Mexican Sinaloa drug cartel, are overtly criminal. Yet, some hybrid criminal actors are making their presence felt even more in some of the islands, and they are arguably even more pernicious and complex to eradicate. They tend to be foreign individuals who operate in both the licit and illicit economies, have become associated with local business elites, and enjoy political connections both at home and in the Pacific.

As their operations have become bolder, as seen in Palau and Papua New Guinea, there are substantiated concerns that the perpetrators may be, or could become, tools of foreign political influence and interference.

The poster boy of this cadre of actors is Wan Kuok Koi, aka Broken Tooth, a convicted Chinese gangster turned valued patriotic entrepreneur. Despite being sanctioned by the US, Wan has leveraged commercial deals linked to China’s Belt and Road Initiative and established cultural associations that have enabled him to co-opt local elites. He has also exploited links with the Chinese business diaspora to identify entry points for his criminal activities (such as establishing online scam centres) and has used extensive political connections to ensure impunity in his operations.

Although they have a lower profile than Wan, many other foreign business actors are active across the region. They often gain high political access, preferential treatment and impunity through the diplomatic relations between their countries of origin (not just China) and the Pacific countries in which they operate. A further risk is that criminal revenues could also be channeled into electoral campaigns, undermining local democratic processes.

These entrepreneurs have exploited favourable tax regimes, limited monitoring and enforcement capabilities and corrupted political connections. They often operate in extractive industries, real estate and financial services.

As bribes pass from hand to hand, and as outside countries weigh their political considerations, Pacific citizens lose out. Some are vulnerable to labour and sexual exploitation at the hands of unscrupulous (and criminal) foreign businesses. Others see their lands, forests and waters degraded, or they are exposed to the introduction of new narcotics for which health services are unprepared.

Fighting this transnational organised crime is critical to strengthening institutions in Pacific island countries and helping them build long-term sustainable prosperity.

Outside countries should consider lateral approaches to crime fighting in the Pacific that may provide a framework for action that is more palatable to island-country governments than more sensitive, purely law-enforcement-driven strategies.

Crime can be both a cause and an enabler of fragility and underdevelopment. With that in mind, the fight against crime and corruption could be framed as necessary primarily to address those two issues. They deeply impact Pacific populations, so it would be crucial to engage with affected communities along the way.

In the absence of such an approach, and with geopolitical and diplomatic considerations taking precedence, criminals will continue to exploit the limited attention that is paid to crime fighting and will profit as a result.