Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Australia has never really had a coherent diplomatic or political strategy in the Middle East, which is puzzling given that we’ve been engaged there in one way or another for a large part of our modern history as a nation. There are many reasons for our shifting focus over the years, although the complexity of the region and the feeling of many in Canberra that it’s all just too hard and the region is a diplomatic minefield are two factors that shape our approach and carry more weight than they probably should.

The vexed issue of the Israelis and Palestinians has in the past few years gained a prominence (if somewhat short-lived) in Australian politics that it hasn’t had for some time. US President Donald Trump’s decision to recognise Jerusalem as the capital of Israel in October 2017 was a once-in-a-lifetime gift to Israel. A year later, Prime Minister Scott Morrison raised the idea of Australia doing the same in the lead-up to the Wentworth by-election, in a move no doubt designed to shore up support from the electorate’s significant Jewish minority. He walked that back somewhat after his party’s candidate failed to secure the seat.

A year later, the policy thought bubble was killed off by the new Labor government, prompting Israel to call in Australia’s ambassador for a ‘please explain’.

Now the Israeli–Palestinian issue is once again leaching into Australian domestic politics. In the lead-up to the Labor Party’s national conference, to be held in Brisbane next week, a relatively symbolic change to policy has, in true Middle East fashion, elicited far more controversy than it deserves. Amid talk of recognising Palestine as a state, Foreign Minister Penny Wong has indicated that the government will return to a previous convention of referring to the ‘Occupied Palestinian Territories’ in line with the United Nations and most of our democratic partners.

There’s little doubt that this move was designed to head off greater demands at the party conference. Realistically, it does not signal a change in Australia’s relationship with Israel other than to recognise the reality of the situation on the ground and to revert to language that was used less than a decade ago.

Nevertheless, the move has elicited criticism, which the government would have expected even if the counterarguments carry little weight. Writing in The Australian, Greg Sheridan argued that they were disputed, rather than occupied, territories, even though they can obviously be both at the same time. The Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council pointed out that the government’s position contradicted the policy position of like-minded democracies such as the US and Canada, but neglected to mention that it aligns us with the position of other like-minded democracies such as New Zealand, the UK and the Europeans. Washington and Ottawa are the democratic outliers in this regard.

Mainstream Australia, as much as it gives it any thought, would likely not look kindly on the government using language that fails to recognise the reality on the ground, particularly when it comes to the vexed issue of Israeli settlements illegally constructed on Palestinian land, an action that has united democracies in opposing it. Even if Australia can do little to stop it happening, the least it can do is recognise it through the language that it uses.

The Arab world ‘has too much history and not enough geography’.

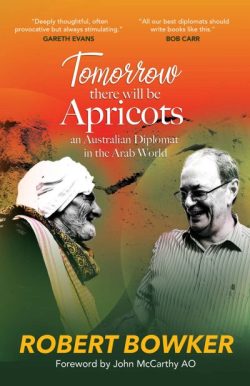

Savour that vivid phrase as the essence of Bob Bowker’s fine memoir of life as an Australian entranced by a Middle East that is crammed full of ‘memories and mythologies’.

Bowker is the ‘dean’ of an exceptional group of Australian diplomats who dedicated their careers to understanding the region. The dean description is from Nick Warner, a Canberra wise owl of foreign policy, defence and intelligence, who says Bowker throws much light ‘on the history of our relationship with the Middle East, where we have gone wrong and right, and what we should do now’.

The book title gives a taste, in several senses: Tomorrow there will be apricots: an Australian diplomat in the Arab world. Bowker explains that the apricot prophecy is a Syrian saying similar to the scoffing English expression, ‘Pigs might fly.’

The hope for apricots, he writes, ‘captures an unquenchable, droll optimism which, together with the deep appreciation of culture and hospitality, ranks highly among the virtues that define what it means to be Arab. It also reflects an abiding scepticism towards the pretensions of those in positions of authority.’

Bowker offers a two-part book in 300 pages. The first half traces his career as a Middle East specialist in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, which he joined as a diplomatic cadet in 1971. The second part, titled ‘Reflections’, is an analysis of the big issues confronting the region.

The two-in-one package offers a fine blend of the personal and the policy, describing a near-50-year journey: 37 years with DFAT and then 12 years as an intelligence analyst with the Office of National Assessments and an academic at the Australian National University.

‘Being an Australian diplomat in the Arab world was more than a career: it was an adventure,’ Bowker writes. ‘In many ways it was my life.’

He notes how former prime minister John Howard labelled himself a cricket ‘tragic’ because he was tragically in love with cricket. Bowker embraces the hopelessly-in-love thought, titling the first half of the book ‘The career of a Middle East tragic’. It’s notable that the book starts with that light-hearted reference to Howard, because one of the great policy fights of Bowker’s career was Howard’s shifting of Australian policy on Palestinian self-determination to lean towards Israel. The diplomat notes he was ‘trumped by the Prime Minister’ and ‘went down in flames’.

A great scene in this flameout has Bowker locked in a shouting match with the prime minister’s foreign policy adviser at the annual conference of the Zionist Federation. Howard was sitting only metres away, preparing to address the conference dinner.

The breach is an example of Bowker’s observation that the policy choices the Middle East has to live with are between bad and much worse.

Tragically in love with the Middle East in all its tragic complications, Bowker offers great yarns, finely told. He has an ear for the telling quote and the eye for a good scene.

Heading off for his first overseas post as a third secretary, only seven months after joining the department, he records the three pieces of advice given him in the conversation that amounted to his consular ‘training’: ‘Never take possession of a corpse. Never take possession of a mad woman. Use your common sense. And that was it.’

At his second post in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, his struggle learning Arabic is illustrated by his regular visit to a roadside stall: ‘I later realised that when I thought I was asking, in terrible Arabic, for a freshly cooked chicken, I was actually asking for a fresh wife. The stall owner didn’t seem to mind.’

Bowker’s ‘colloquial Levantine Arabic’ had many uses beyond talking to taxi drivers. To impose some ceremonial pain on Sudan’s president for atrocities by his tribal proxies in Darfur, the ambassador gave ‘my speech on presentation of my credentials in Arabic’.

In a gem of a chapter titled ‘Touring Tobruk by moonlight’, Bowker captures Libya’s ‘blend of chaos and impenetrability under the Ghaddafi regime’ by describing his scouting trip, as the non-resident ambassador, for a prospective visit by the Australian defence minister to a war cemetery.

Two Libyan minders drive him from Benghazi in a car that ‘sounded very sick indeed’ to tour a range of war cemeteries—British, French and German—but can’t find the Australian site until the moon is out. At the end, the minders have an animated discussion about the report they must file ‘on why the ambassador chap had been scoping out the port area and surrounds of Tobruk, especially the high ground overlooking the harbour, quizzing the local about the layout of the urban area, and doing so in execrable Arabic’.

When they got back to Benghazi at 0130, one of the minders ‘shook my hands and planted kisses on both my cheeks. When you are kissed by a Libyan security official, you know it is time to go home.’

Writing of his time in Syria in the 1970s, Bowker recounts a local quip: ‘Saudi Arabia exports oil, Iraq exports dates, Egypt exports jokes and Syria exports trouble.’ The three-line description of then-president Hafez al-Assad is a miniature masterpiece of disdain: ‘His smile was like moonlight on a tombstone’; Assad had a ‘penchant for delivering historical lectures’ and dominated meetings with ‘his awe-inspiring bladder control’.

Bowker’s sad conclusion is that the Assad family—Hafez and now his son Bashar—has become a regime that outlasted the country. The bedrock of Bashar’s rule is its brutality, he writes, and father and son always avoided ‘questions about the appropriate relationship in Syria between state and society’.

In his reflections, Bowker considers the department that made his career, lamenting how the role of Australia’s diplomats in Canberra has changed, ‘and not for the better’.

DFAT, he argues, gives priority to trade and consular crisis management ahead of the research and thinking needed for effective foreign policy planning and advocacy. Policy is ‘created in ministerial offices, with DFAT seen more as an implementing agency for those outcomes. This is a deeply problematic direction for any government, or government department, to take.’

DFAT no longer debates with itself and the rest of Canberra through dispatches and cables: ‘The final decade or two of my time in the department saw a shift to reporting by cable that was prone to be concise rather than nuanced. It was directed in its brevity towards immediate briefing needs, rather than the evaluation of trends and their consequences for Australian interests.’ Under the Howard government, he notes, the lengthy dispatch from a post became a thing of the past: ‘By the time I retired it had become almost unthinkable to reflect on broader issues, let along to challenge policy settings, in cable traffic.’

Bowker tackles three core questions in his reflections:

1. ‘How do you build peace between two peoples—Israelis and Palestinians—with compelling national rights, human rights and historical narratives, but who have a clear imbalance of power?’

2. How does one connect the present, the past and the politics of Palestinian identity? This is an intellectual who 20 years ago wrote the book Palestinian refugees: mythology, identity and the search for peace. As a diplomat, he offers the answer (‘if there is one’) of negotiating on interests, because beliefs are ‘organic, structural and fundamentally non-negotiable’.

3. How does the Arab world confront its demographic fate (a Middle East population of 724 million people by 2050) and its economic and social challenges while preserving its Arab and Islamic identity? ‘None of the current leaderships of the major Arab states and Iran have answers to the problems of legitimacy and governance,’ Bowker writes. His fear is that governments will ‘grow more authoritarian, transactional and violent in their instincts and behaviour’. Defending privilege and predictability, rulers have found that repression works for them, arguing that ‘freedom is more likely to produce chaos and division rather than bread and social justice’.

The Arab outlook, Bowker observes, feels like being on the bridge of the Titanic smelling the ice. It took the Titanic a long time to sink, though, and the modern Arab world has no way to stop the drivers of change, which are ‘generational and societal as well as political’.

On the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, Bowker declares that the two-state approach pursued since the 1990s ‘is dead’. He pointedly calls it a two-state ‘approach’ because no solution is in sight.

If the two-state approach is mired in fundamental conundrum, he argues, the path to justice is by ‘building a foundation for Palestinian rights and dignity among Israelis’.

Israel can facilitate a new, more positive future for Palestinians and Israelis, he says, without raising existential questions for Israel: ‘The absence of sovereignty is a legitimate grievance for Palestinians, but in practice it is the absence of dignity and economic security that matter much more.’

If the two-state option is dead, as Bowker avers, then Palestine’s dream of independence must fade. As The Economist wrote recently, the Palestinian diaspora has ‘begun to call for a one-state solution, where Jews and Arabs between the Jordan rivers and the Mediterranean would live together in a single democratic state—and where Arabs would have a slender overall majority’.

For Israel and the Arab world, demography should meet democracy, and history must reconcile with geography.

In a piece for The Strategist two years ago, Bowker wrote that ‘the convenient fable of a two-state solution’ has to be challenged: ‘A one-state approach would require mobilising political support for a fundamental rearticulation of the political, security and social apparatus and identity of Israel.’

Bowker concludes that the fun and frustrations of his life as a Middle East tragic have forced acceptance of key realities.

Middle East policy is not a morality play, he writes. Expediency shapes decisions: ‘The logic of strategy is not always consistent with the logic of politics.’

Diabolic complexity rules. The nature of the Middle East is for problems to linger and become more complex, Bowker writes: ‘We must accept that views, interests and values within Arab societies are more likely to differ from our own: any apparent synchronicity of views should be cause for caution, as well as celebration.’

The final sentence of this tragic’s meditation on his life’s works reads: ‘And, despite almost 50 years of exposure to the Arab world, I remained free of tribal delusions, except where Collingwood is concerned.’

Ah, the Melbourne conundrum of the Collingwood Football Club—the one passion running through this fine book that (in the tribal view of this reviewer) does not bend towards truth and logic.

Religion and miracles often go hand in hand, so it should come as little surprise that Israel, which just marked its 75th birthday, is something of a miracle. In some ways, Israel’s very existence is miraculous, as the newborn state only narrowly avoided being strangled in the crib by the much larger armies of its Arab neighbours, which invaded in May 1948.

Since then, Israel has weathered many more wars, along with a host of lesser attacks. But the larger story is that Israel has not only survived but thrived.

Today, it is a country of nearly 10 million people. It is a democracy in a part of the world dominated by authoritarian regimes. Despite not having any natural resources to speak of, its economy, boasting a world-class technology sector, is booming. Annual GDP per capita is around US$55,000, putting it among the world’s top 20 countries, ahead of Canada, Japan and much of Europe.

Israel’s extraordinary accomplishments are one reason that many of the country’s Arab neighbours have come to accept its existence. Israel now enjoys formal peace with Egypt and Jordan as well as with Morocco, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. It has informal and growing ties with other Arab states, including Saudi Arabia, as the region’s focus adjusts to a reduced American presence and with Israel seen as an important partner in efforts to confront threats posed by Iran.

But Israel’s future remains uneasy and uncertain.

First, there are the continuing external threats. Among them are Syria, which has become a safe haven for Iranian proxies amid its civil war, and Lebanon, where Hezbollah has established what is effectively an Iranian-backed state within a state just across Israel’s northern border, with more than 100,000 rockets pointed south. And Iran itself now can produce in a matter of weeks enough enriched uranium for several nuclear bombs, meaning it is nearing the capability to threaten Israel with an attack.

A massive problem for Israel remains the unresolved Palestinian issue. This is largely the result of the June 1967 Six-Day War, a conflict that changed Israel’s trajectory.

There are now some five million Palestinians living in lands occupied by Israel. Negotiations to create a separate Palestinian state came close to succeeding on several occasions. I would argue that Palestinians’ refusal to accept what was offered (however imperfect) reflected a colossal failure of leadership; but regardless of how we reached this point, it’s clear that prospects for a two-state solution are increasingly remote given Israeli and Palestinian politics alike.

This is obviously bad for Palestinians, but it’s also bad for Israel’s democracy and security. Continued occupation will require a major, and perpetual, military presence and weaken Israel’s standing in the world.

A third challenge is internal. Israel was founded primarily by Jewish refugees from Europe. Subsequent large waves of immigrants came from the Middle East and the former Soviet Union. Today’s Israel is made up of these immigrants and their descendants, along with Christians and Muslim Arabs (often called Israeli Arabs or Israelis of Arab descent) and their descendants who were living within Israel’s modern borders before and after 1948.

The result is that Israel is approaching fundamental choices about its identity. If it wants to remain a democratic state, it cannot forever rule more than five million Palestinians and deny them citizenship and the rights that go with it. But if it wants to remain a Jewish state, it cannot rule over a country that adds five million Palestinians to its existing population of two million Israeli Arabs. Something has to give.

There is one additional dynamic: the rapid growth of the ultra-orthodox Jewish population, which now includes some 1.3 million, or 14%, of Israelis. Their religious views exert a major influence on their thinking about how Israel ought to be organised and run.

While military service is mandatory for Israelis, there’s an exception for the ultra-orthodox, most of whom choose not to serve. Many of them study and pray rather than work or otherwise contribute to the economy. Through the political process, they seek to bring about a society in which religious interests, as they perceive them, take precedence over the desires of secular Israelis. Demographic trends suggest that they could eventually succeed.

The result is that Israel at 75 faces challenges that are no less existential than those posed by the invading armies during its early history. Recent protests over proposed changes that would increase political control over what has been a highly independent judiciary highlight that Israel is a polarised democratic country. Alas, it’s far easier to describe the problems than to suggest how they might be resolved.

All this has created a new issue. Israel has accomplished most of what it has through its own efforts, but it has been aided for most of its history by the substantial economic, military and diplomatic support of the United States, and by the philanthropy of American Jews. It is increasingly unclear whether such support will be as forthcoming if Israel is viewed as undemocratic and embracing religious extremism.

All this will worry Israel’s many friends around the world who admire the country’s achievements and wish it well. Less certain is whether it will also worry Israelis enough for them to make some difficult but necessary choices.

Planet A

Updates to Australia’s emissions reduction ‘safeguard mechanism’ will limit new gas and coal investments while hard-capping total greenhouse gas emissions. The initiative, which comes into effect on 1 July, targets 215 major polluting facilities including fossil-fuel operations, other mines, refineries and smelters that together emit more than 100,000 tonnes of CO2 annually, or roughly one-third of Australia’s carbon pollution. The law will require producers to reduce their emissions by 5% each year, either through their own cuts or by purchasing carbon offsets. They are not permitted to increase their total emissions and must ensure they decline over time.

Australia aims to reduce its carbon emissions by 43% from 2005 levels by 2030 and to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, aligning more closely with UN goals. The government anticipates that the changes will enable the country to capitalise on decarbonisation possibilities and fulfil ambitious climate objectives. The Australian Greens backed the legislation despite their concern that it did not do enough to limit the use of coal and gas. While the government sees gas as a transitional fuel on the way to more extensive use of renewables, some analysts argue that gas is not the answer and will become too expensive to use. Those backing the changes to the law say it is necessary to reduce Australia’s vulnerability to extreme weather events such as bushfires, droughts and floods.

Democracy watch

Thousands of Kenyans have marched in anti-government protests coordinated by opposition leader Raila Odinga, who has accused President William Ruto of stealing the 2022 election. Odinga suspended a fourth ‘mega’ rally scheduled for Monday after an appeal from Ruto, but warned that demonstrations could resume if negotiations broke down.

Four protestors and one police officer have died since the protests began on 20 March, and 22 journalists have been injured by police and violent protesters. Ahead of the rally, the Kenya Media Sector Working Group said it had been told that the government planned to shut down the broadcast media and internet. Ruto publicly rejected the allegations and said his party had no intention of denying the free flow of information to the public.

The unrest has alarmed Kenya’s neighbours and allies and driven fears that the situation could escalate into a repeat of the ethnic violence seen after the 2007–08 elections, which left more than 1,100 people dead.

Information operations

Leaked corporate documents have focused attention on a disturbing partnership between Russian intelligence agencies and the Moscow-based defence contractor Vulkan. The documents reveal plans to augment Russia’s cyberattack capabilities, disseminate disinformation and conduct surveillance of the internet. They have exposed databases that can help identify and list vulnerabilities in global computer systems, potentially enabling targeted attacks.

The US has accused Sandworm, a state-sponsored hacking group, of exploiting Vulkan’s technology to cause power outages in Ukraine and to interrupt the opening ceremonies of the 2018 Winter Olympics. Sandworm has also been blamed for the NotPetya ransomware attacks.

The documents also expose numerous software programs engineered to automate disinformation campaigns and attacks on critical infrastructure. Of particular concern is Amezit, which allows the Russian military to hijack domestic and international information flows and conduct large-scale covert disinformation operations on social media and the broader internet by creating realistic avatars with stolen personal photos. That is intended to contribute significantly to the development of offensive cyber capabilities by Russia’s military intelligence service.

Although no conclusive evidence of the systems being used in actual cyberattacks has yet been found, several Western intelligence agencies and independent cybersecurity companies consider the documents to be authentic.

Follow the money

On 1 April, the United Arab Emirates and Israel ratified a ‘historic’ free-trade agreement that eliminates or reduces tariffs on 96% of goods. Initially conceived in May 2022, this deal has now taken effect as a comprehensive economic partnership agreement. This is Israel’s first free-trade agreement with an Arab country and builds on the normalisation of diplomatic relations between Israel and the UAE in 2020 precipitated by their shared apprehensions about Iran.

In addition to novel tariff structures, the agreement removes trade barriers, enhances market access for service providers, delineates digital trade parameters, safeguards intellectual property and creates transparent dispute-resolution mechanisms. It is expected that the agreement will raise bilateral trade to more than US$10 billion and boost the UAE’s GDP by US$1.9 billion within five years. The agreement also reflects Israel’s efforts to bolster its ties with the UAE and normalise relations with other Arab nations.

The deal flows from UAE initiatives to build a stronger and more resilient economy. The UAE plans to start negotiations for a trade deal with Ukraine soon, after successfully concluding comprehensive economic partnership agreements with India and Indonesia as part of its plan to double its economy to US$817 billion by 2030.

Terror byte

The militant Islamist movement Boko Haram has surged in northern Nigeria, with Borno state the epicentre of its campaign of violence. The Council on Foreign Relations says that between May 2011 and March 2023 violence in the state, much of it perpetrated by Boko Haram, claimed the lives of more than 37,500 people—almost 40% of all reported deaths in the country during that period.

In 2016, Nigerian authorities established a safe exit program to degrade the fighting power of terror groups. While hundreds of defectors have graduated from the six-month physical, mental and psychosocial rehabilitation program, weak institutions and poor governance have enabled Boko Haram to regain strength.

Stepped-up efforts haven’t stopped the violence from expanding into neighbouring Cameroon. Last week, at least three civilians were wounded when Boko Haram raided villages in Amchide and Kolofata. That followed the death of at least one Cameroonian defence force member in a landmine explosion that injured several others.

In his address to the UK House of Commons last month, Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky declared: ‘We built a coalition of air defence, which allows us to save the lives of our children, of our people, of our civilians, our women, our elderly, and our cities from atrocious Russian occupation and missile terror.’

As Russia has stepped up its missile and drone attacks on Ukrainian population centres, much attention has focused on the role of missile-defence systems. Anti-missile shields are designed to undermine an adversary’s confidence by heightening uncertainty and degrading its missile capabilities while strengthening the morale of those attacked. Their effectiveness is studied closely by military establishments including in Israel, which has contended with regular rocket and missile attacks for decades.

In the early months of Russia’s invasion, Ukraine’s population and infrastructure were exposed and vulnerable to missile attacks. Between February and May, Moscow fired more than 2,000 cruise and ballistic missiles in an attempt to destroy Ukrainian air defences. During March and April, Ukrainian defenders intercepted 20–30% of them.

Russia began targeting sites such as government buildings and telecommunications infrastructure in an attempt to damage resistance and morale. By June, targets included critical energy facilities and railway lines. Ukrainian air defences were reorganised and redeployed to protect cities and important infrastructure, and interception rates reaches 50–60%. Ukraine’s S-300 systems have been effective against Russian cruise missiles, particularly when they received early warning of launches.

Ukraine’s growing ability to intercept missiles was a factor in Moscow turning to Iran for large numbers of Shahed-131 and Shahed-136 uncrewed aerial vehicles, which have become an integral part of Russia’s missile war. They have been used alongside cruise missiles, targeting critical infrastructure in key cities. The UAVs are small, have pinpoint precision and are very effective. They fly low, which creates problems for air defences. By the time they’re detected, it’s often too late to shoot them down.

Yet Ukraine now claims to have intercepted close to 90% of them, reflecting the growing effectiveness of its defences. While Ukraine is exhausting its ammunition supplies at an alarming rate, Russia’s stock of Iranian drones is also diminishing because it uses vast swarms to penetrate Ukrainian air defences. Moscow is being forced to ramp up its own arms production at great cost to its economy.

According to Mykhailo Samus, a military expert in Kyiv, Moscow can’t afford to exhaust its missiles because of the adverse implications for its forces. As Ukraine receives more support for its air and missile defences, Russia’s stocks will be degraded. To sustain the war, Russia is likely to shift the costs of replacing degraded stocks to its population and businesses.

Uzi Rubin, a leading Israeli missile expert, says air and missile defences can’t provide hermetic protection anywhere. While Ukraine has intercepted many missiles, Rubin maintains that it’s a quantity game and one battery does nothing. ‘If you manage to shoot down nine out of 10 missiles, then the damage and casualties are limited. This gives Ukraine the staying power to keep fighting. Defence matters.’

The US announced in December that Ukraine would receive a Patriot system, one of the world’s most advanced long-range air-defence systems, which can intercept cruise missiles, ballistic missiles and aircraft with great accuracy. Germany and the Netherlands have also offered to send Patriots. France and Italy will supply Ukraine with the SAMP/T air-defence system, which is unique as a European system that can intercept ballistic missiles. Samus says these additions will significantly improve Ukraine’s defences. These developments are crucial for Ukraine to resist Russia’s onslaught, but US officials say there’s ‘no silver bullet‘ and their goal is to help Ukraine ‘strengthen a layered, integrated approach to air defence’.

Ukraine’s capabilities have dramatically improved and Western air-defence systems such as NASAMS and IRIS-T have bolstered its ability to intercept missile barrages. The Patriots are intended to strengthen Ukrainian fortitude in the face of this onslaught and the multi-layered approach mirrors that of Israel in confronting the threat posed by Iran and Hezbollah.

Israel is under growing pressure to supply missile defences to Ukraine but has refrained from doing so for fear of angering Russia, which could constrain its freedom of action in striking Iran’s forces in Syria. The US has made its annoyance over Israel’s position clear. However, it will be increasingly difficult for Israel to sit on the fence given Russia’s ever closer military cooperation with Iran.

Israel’s foreign minister, Eli Cohen, visited Ukraine in February and told Zelensky that Israel would supply Ukraine with an aerial threat early warning system. More recently, Israeli and Ukrainian officials announced that Israel has approved export licences for anti-drone systems for Ukraine. This will allow Israel to assess how effective its systems are against Iran’s drones. Zelensky told Cohen that Iran is a ‘common enemy’. Samus maintains that every bit of support Ukraine receives is significant and hopes that this will presage Israel’s delivery of the David’s Sling or Arrow 3 system.

There’s no room for complacency about Russia’s missile threat. The Conflict Armament Research group says that while Russia has likely used a significant portion of its stockpile, the production of guided cruise missiles such as the Kh-101 and the stockpiling of critical electronic components have continued in spite of Western sanctions.

Critically, the US has long viewed missile defences as a means to strengthen the morale of allies exposed to missile attack, including Israel. The White House’s 2022 missile defence review says that ‘missile defence capabilities add resilience and undermine adversary confidence in missile use by introducing doubt and uncertainty into strike planning and execution’. The supply of Patriot missiles reassures the Ukrainian people, cements Washington’s political commitment to their defence and strengthens their resolve. As Samus points out: ‘Missile defence is a part of resilience. For Ukrainians, even electricity depends on missile defence. Protecting houses depends on missile defence.’

Israel knows from its own experience of missile warfare how essential air defences are to sustain fortitude and resilience. Yet it’s likely that Iran’s close support for Russia, rather than US pressure, will shift Israel’s calculus on military support for Ukraine.

Hostility between Israel and Iran has potentially reached a tipping point. They have been conducting covert operations against each other for years, but Israel’s recent drone attacks on Iranian military facilities in the province of Isfahan were the most daring move yet. Tehran has promised retaliation at a time of its choosing. The two protagonists are now closer than ever to a major confrontation, by design or by accident. A war would not be confined to them. It could easily set off a devastating regional inferno with implications far beyond the Middle East.

US sources have confirmed that Israel was responsible for a series of attacks by bomb-carrying drones on military sites in Isfahan, where Iran’s nuclear facilities are located, on 28 January. The two sides have been at loggerheads since the advent of the Islamic regime in Iran 43 years ago and its denunciation of Israel as an expansionist ‘Zionist state’. But Israel’s latest operation was its first direct air attack on Iranian soil.

Up to that point, the arch foes had largely contended with a shadowy war. Israel acted remotely to diminish Iranian military and intelligence capability. Its actions involved targeting Iranian nuclear scientists and killing several of them, including the father of Iran’s nuclear program, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, in 2020, and launching cyberattacks on Iranian nuclear plants, the biggest of which was the Stuxnet computer virus, in 2010, which damaged the Natanz facility. It also assassinated a few top officers of Iran’s powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, bombed Iranian targets in Syria and Lebanon on an ongoing basis, and hit or neutralised Iranian oil or cargo ships. This has all been part of an Israeli strategy to ensure that Iran is prevented from developing a military and nuclear capability that poses a threat to Israel.

In turn, Iran armed allied Lebanese Hezbollah to the teeth and supported the Palestinian Islamic movement Hamas and Islamic Jihad in Gaza against Israel. It also targeted Israeli ships in the Persian Gulf and the country’s Mossad intelligence operatives and embassy personnel wherever and whenever feasible. Many alleged Iranian intelligence operations against Israeli targets were reported in the Middle East, Asia, Europe and Latin America. In addition, acting through Hezbollah, it flew drones over Israel and backed operations on the Syrian border of the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. It also backed Hezbollah’s encounters on the Israeli–Lebanese border. All the while, it sought to obtain intelligence about Israeli capabilities in a variety of ways and means.

In the process, Iran has strengthened its ties with Russia and China to rebuff Israel–US pressure, but in a complicated regional setting. Tehran has operated in alliance with Moscow in support of the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria, backed Russia’s Ukraine aggression politically and materially, and signed a long-term agreement of strategic cooperation with China.

Israel has endeavoured to have good relations with China, involving intelligence and military cooperation, and to avoid upsetting Russian President Vladimir Putin. It has sought to promote itself as a mediator in the Ukraine conflict, though to no avail, and refused to join the US and, for that matter, America’s European allies, in supplying Kyiv with its Iron Dome air-defence missiles. Its approach is guided by an interest to keep Russia on side so that it can maintain access to Syrian air space to bomb Iranian targets.

Concurrently, the fear of an ‘Iran threat’ has played a critical role in normalisation of relations between Israel and some of the Arab states of the Persian Gulf (the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, in particular) with the blessing of Iran’s other regional rival, Saudi Arabia, in a united anti-Iranian front, though at a cost to the Palestinian cause.

However, Israel’s direct drone attacks on facilities in Isfahan, the extent of damage to which is unknown, have taken the Israeli–Iranian enmity a dangerous step closer. It has occurred at a time when Israel is being run by the most right-wing government in its history, led by Benjamin Netanyahu. The new administration has vowed to do whatever is necessary to stop Iran producing a nuclear bomb, thus preserving Israel’s status as the sole military nuclear power in the region. At the same time, despite the public protests that have rocked Iran since last September, the Islamic regime has remained determined to counter Israel and its allies by accelerating its nuclear program and maintaining its regional influence in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen as central to a broad security architecture in the region.

The scene is set for a potential war, but both sides are also cognisant of the devastating costs of such an event. This is what has deterred them so far, and one should hope that this will remain the case.

At its latest meeting, the Be’er Sheva Dialogue pursued a fresh path to advance security cooperation between Australia and Israel in the face of a worsening strategic outlook. The war in Ukraine and Chinese belligerence in our region cast shadows over the dialogue, held in Canberra last week.

The dialogue is the peak independent platform for security exchange between the two nations. It is named after the Battle of Be’er Sheva (Beersheba in English), the victory over the Ottoman Turks led by British, Australian and New Zealand troops on 31 October 1917.

The dialogue has advanced ideas to intensify the security relationship between our two countries in the eight years since it was co-founded by ASPI. Now, in the face of growing threats, the dialogue is stressing the need for Australia and Israel to work even more closely in a range of areas, including defence. That means establishing military-to-military talks, military college exchanges, military medicine linkages and Israeli defence production in Australia. Other key areas for closer cooperation are cybersecurity, counterterrorism, critical technologies such as artificial intelligence, quantum computing and machine learning, and space with opportunities to develop small satellites and potentially to launch Israeli satellites from northern Australia. Israel is keen to learn from Australian approaches to natural disaster management and to share its own experience in managing mass-casualty incidents.

The dialogue was opened by Australia’s deputy prime minister and defence minister, Richard Marles. Israeli participants included Major General Eyal Zamir, the former deputy chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces; Brigadier General Yossi Kuperwasser, who led the research and assessment division of Israeli military intelligence; Ehud Yaari, Middle East commentator for Israel’s Channel 12 television; Zohar Palti, former head of the policy and political-military bureau at Israel’s Ministry of Defence; and Mark Regev, head of the Abba Eban Institute and former prime ministerial adviser and international spokesperson.

Israeli participants discussed their country’s changing relationship with China, which has long sought access to Israel’s innovation sector. While Israel had earlier focused on seizing economic opportunities, the country was now taking concerns about China seriously and viewing relations more through a national security prism. Israel has, for example, largely excluded Chinese companies from multiple infrastructure projects.

On Ukraine, Australian delegates heard how Israel had reached practical understandings with the Russians to enable the Israeli military continued freedom of action against Iranian and other targets in Syria. There’s continued Western pressure on Israel to provide Ukraine with air-defence systems against missiles and kamikaze drone attacks. While Israel has so far refrained from providing such assistance (although it has provided humanitarian aid), it was made clear that as a free liberal nation Israel isn’t neutral when it comes to superpower rivalry.

As laid out during the dialogue, there’s growing cooperation between three powerful autocracies: China, Russia and Iran (which continues to use proxies like Hezbollah and Hamas and has supplied drones to Russia). Along with North Korea, the meeting discussed how this rectangle of rogue nations requires cooperation between Australia and Israel to respond to a common challenge.

The dialogue noted that forces in modern conflicts needed the cutting edge provided by emerging technology and how that urgency has driven Israel to develop rapid processes for getting capabilities into the hands of its military.

Australian delegates suggested that because we could now be drawn into a military conflict with little warning, we could not afford our slow-food approach to the enhancement of weapon systems required for high-end warfighting. We can learn from Israel’s experience in acquiring cutting-edge capabilities. It was suggested that Israel and Australia should establish a counter-drone taskforce.

Participants discussed Russia’s use of hybrid warfare and information warfare techniques in Ukraine. The war has been a hotbed of experimental tactics, doctrine and technologies, but many of Moscow’s efforts have proven less impressive than expected. Israel and Australia could share insights on successful information operations with our allies and partners.

In our near region, where we need all the friends we can get, the Pacific island states trust Israel. There’s a host of opportunities in the South Pacific for our two countries to focus on practical issues in which Israel has expertise: climate resilience, health, agriculture, water filtration systems and green energy. The islands look to Israel to support their 2050 strategy for the Blue Pacific continent. Israel has included marine technology as a top research priority. An Israeli company has, for example, developed marine-friendly concrete for use underwater, which is especially relevant to the islands.

In opening the dialogue, Marles said:

Australia looks to Israel as an example of a nation which has been a leader in defence strategic thinking—be it in regard to its defence industry capabilities (and the innovation system, economy and workforce built around that) or in regard to its deep cultural relationship with science and technology. As we look forward, we need to think about how we can continue to deepen our bilateral relationship, which also extends to the relationship between our militaries and defence industries.

After eight successful years of the Be’er Sheva Dialogue putting more meat on the bones of Australia’s security relationship with Israel, there’s much more to be done in working together in the heightened strategic circumstances both countries face. We need all hands to the pump.

The Middle East is learning to live without America. While the United States will continue to shape regional security, not least through its advanced weapons systems, its (perceived) retreat from the Middle East has raised serious doubts about its willingness to fulfill its commitments to its allies. Now, local actors are revising their geopolitical strategies, with old enemies pursuing reconciliation and some countries even seeking to create a system of collective security. To deliver regional peace and stability, however, countries will have to overcome even bigger hurdles than they seem to realise.

Middle Eastern leaders’ disillusionment with the US has been growing for more than a decade. Autocratic Arab rulers accuse the US of betraying them during the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings, by aligning with the forces trying to overthrow them. They also blame the US for effectively negotiating the 2015 Iran nuclear deal behind their backs, and for failing to discipline Bashar al-Assad’s murderous regime in Syria.

More recently, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates were none too happy with America’s non-response to attacks by Yemen’s Houthi rebels on their oil infrastructure. That probably explains, at least partly, why neither country has been willing to meet US President Joe Biden’s requests to boost oil and gas production to contain surging energy prices amid the Ukraine war. Reportedly, they won’t even take his calls.

Instead, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are continuing down the path onto which they stepped at last August’s Baghdad summit, which was convened in an effort to defuse regional tensions. This includes efforts to improve relations with Iran, in hopes of bringing an end to the war in Yemen. The UAE has also re-established diplomatic relations with Assad, whom the US wants to continue treating as a pariah. Assad even visited Abu Dhabi last month—his first official visit to an Arab country since the Syrian civil war began more than a decade ago.

Turkey has similarly adopted a more conciliatory approach towards Assad. Turkey cut all diplomatic ties with Syria in 2011, and long insisted that there could be no peace as long as the ‘terrorist’ leader was in power. But Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is now seeking an agreement that guarantees that northern Syria will never become an autonomous Kurdish region, and that the millions of Syrian refugees in Turkey can go home.

This is but one facet of a broader Turkish foreign-policy recalibration, spurred by deep regional isolation and severe economic crisis. Despite being a traditional ally of Qatar—the nemesis of the rest of the Gulf states—Turkey recently re-established diplomatic ties with the UAE and engaged in dialogue with Bahrain. Erdogan even seems to be planning to visit Saudi Arabia.

Moreover, Turkey has sought reconciliation with Israel, with Israeli President Isaac Herzog making an official appearance in Ankara last month. This shift reflects Israel’s improving reputation in the Middle East as a legitimate ally, as well as Turkey’s hope to capitalise on the eastern Mediterranean gas bonanza.

Turkey has also pursued a thaw in relations with Egypt, which, like Israel, is a major player in the East Mediterranean Gas Forum, from which Turkey has so far been excluded. With Europe desperately searching for alternatives to Russian gas, Erdogan is eager to facilitate the transfer of Egyptian and Israeli gas across the Mediterranean.

But while this reshuffling of bilateral relationships has important implications for Middle Eastern security, it lacks the transformative potential of an inclusive multilateral structure for ensuring regional peace and security. Such a structure might seem farfetched, given the seeming intractability of the Arab–Israeli conflict, at the heart of which is Israel’s occupation of Palestinian lands.

But the 2020 Abraham Accords—under which the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan normalised diplomatic relations with Israel—raised hopes that Arab–Israeli cooperation would be possible. And, at last month’s Negev Summit—hosted by Israel and attended by the foreign ministers of Bahrain, Egypt, Morocco and the UAE, as well as US Secretary of State Antony Blinken—those hopes seemed to be materialising. Participants pledged to expand cooperation to cover energy, environmental and security matters, and to attempt to engage additional countries.

That’s good news for Arab governments, for which the threat of a nuclear-armed Iran, together with the proliferation of jihadist activities, has bolstered the appeal of a regional security agreement. But one group was conspicuously absent from the summit: the Palestinians.

With their hopes of an independent state dwindling, some young, desperate Palestinians have made their dissatisfaction known through a wave of terror attacks against Israeli civilians. This suggests that a grand Arab–Israeli regional initiative that excludes the Palestinians may well prove unsustainable.

As long as Palestinians feel trapped under Israeli occupation and abandoned by their Arab brethren, some will view terrorist acts as their only option for fighting back. Amid escalating violence—which would surely trigger an escalating Israeli response—Arab leaders would face popular pressure to sever ties with Israel.

Furthermore, while they are willing to work with Israel to bolster regional security, Arab countries don’t view the Negev alignment as the only option for dealing with Iran; they’re also pursuing diplomacy—and rightly so. But the Palestinians also deserve peace diplomacy. Instead of attempting to push the Palestinians’ plight onto a back burner, the regional concert of powers seeking to build a more secure Middle East must address it head on. As Jordan’s King Abdullah II recently noted, his country, too, must be involved.

The war in Ukraine has shown that security frameworks that exclude anti–status quo powers are fundamentally fragile. In this sense, the Negev alignment has an even more challenging—and vital—diplomatic mission than its participants seem to realise. In building a post-American regional security structure, they must integrate both the Palestinians and the Iranians—the two revisionist forces that the US failed to pacify during its decades of Middle Eastern hegemony.

The Ukraine crisis has confronted three Middle Eastern countries—Turkey, Israel and Iran—as well as India, with serious policy quandaries. For different reasons, they face the conundrum of how to strike a balance between opposing Russia’s aggression against the sovereign state of Ukraine and maintaining good relations with Moscow. So far, they have walked a tightrope, but now with Russia’s invasion in full swing they need to show their hands more clearly.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose country is a member of NATO, has built a good working relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin over the last few years despite their differences in Syria and past stoushes. He has tilted towards Moscow to counter what he perceives as America’s and Western Europe’s unfavourable treatment of him, especially in the wake of the failed 2016 coup against him and his harsh crackdown on the opposition. He has purchased Russian S-400 surface-to-air missiles to the annoyance of the United States, which in turn has dropped Turkey from its F-35 fighter jet program.

Meanwhile, Erdogan has maintained good relations with Ukraine and strongly supported the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the country. In the lead-up to the Russian invasion, he called for a diplomatic resolution of the crisis and avoided any direct criticism of Russia. Now, however, he needs to decide whether to side with Turkey’s NATO partners or take an independent course that could further aggrieve those partners.

Putin’s actions have also placed Israel in a difficult position. It is concerned about Russian aggression and has good relations with Ukraine, whose president is Jewish. But it has been careful not to antagonise Moscow. Putin has stood by Israel despite the Jewish state’s brutal treatment of the Palestinians under occupation. Yet, he has also politically and militarily backed the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad in a de facto alliance with Iran, which Israel regards as an arch regional enemy. Israel needs Moscow’s understanding for hitting the Iranian forces and those of the Iran-allied Lebanese Hezbollah in Syria.

Although Moscow has occasionally been critical of Israel for violating Syrian sovereignty and air space when regularly bombing Iranian and Hezbollah sites, it has been reluctant to take on Israel as long its missions have not caused any problems for Russia on the ground. Israel would like to see this status quo maintained.

Iran has backed Russia’s Ukraine adventure, as expected given Tehran’s dependence on Moscow for weapon supplies and coordinated actions in Syria. Beyond this, Tehran needs Moscow’s support in the ongoing negotiations in Vienna on reviving the multilateral 2015 Iran nuclear agreement, which US President Donald Trump rescinded in 2018 and his successor Joe Biden wants to rejuvenate.

This doesn’t mean that Tehran is very trustful of Russia; to the contrary, the two countries have had bitter moments in their historical relations. But Tehran sees benefits in not being critical of Moscow over Ukraine. Yet, in the process it risks provoking American displeasure at the nuclear talks, unless it changes its position from indirect to direct dialogue with the US.

India has found itself in a very awkward foreign policy situation. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s right-wing Hindu government has developed close relations with Washington, leading India to join the US, Japan and Australia in the Quad alliance, which is broadly viewed as an anti-China measure. However, New Delhi also has very close defence cooperation with Russia, which is a major weapons supplier to India. Primarily for this reason, Modi has so far adopted a position similar to that of Erdogan on the Ukraine conflict—essentially avoiding taking sides, though in a phone call with Putin he did appeal for an ‘immediate cessation of violence’.

Modi is under increasing pressure, at least indirectly, from the other Quad members, which have strongly condemned Russia’s actions and imposed sanctions on the county. Now, in the wake of the Russian invasion, New Delhi is further pressed to adopt a clearer posture. If it tries to please Moscow, India is likely to be viewed as a very weak link in the Quad, and if it adopts the Quad’s position, it will likely risk relations with Russia.

The Ukraine crisis is indeed globally multidimensional. While it has proven to be quite straightforward for most Western countries to oppose Russia, the same cannot be said for those states that find themselves caught between the West and Russia.

Much speculation surrounds the negotiations in Vienna aimed at reviving the Iran nuclear deal (formally, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action) as they near their final phase. The latest statements emanating out of Washington signal a cautiously optimistic note. According to a senior US State Department official, the negotiations over the past month ‘were among the most intensive that we’ve had to date … [W]e made progress narrowing down the list of differences to just key priorities on all sides. And that’s why now is the time for political decisions.’

The same official expressed a great sense of urgency that the negotiations be concluded soon since Iran is now very close to ‘breakout time’, meaning it has enough fissile material for a nuclear weapon. ‘[W]e’re talking about weeks, not months,’ the official said.

It appears that the technical issues have been sorted out and it’s now up to the highest authorities in Tehran and Washington to determine how to narrow the gap in expectations on both sides and find a compromise formula. Washington’s apprehensions about Iran reaching breakout point and the Iranian regime’s need to reverse the perilous state of the country’s economy indicate that a compromise agreement is likely to be hammered out soon, possibly in a few weeks’ time.

The prospect of such an outcome has Israeli leaders worried. Although Prime Minister Naftali Bennett’s government has adopted a far less provocative posture towards President Joe Biden’s administration than did Benjamin Netanyahu’s government, its stance on the issue of a return to the JCPOA is pretty much the same. After initially soft-pedalling the issue, Bennett has clearly declared that a revived JCPOA will not be acceptable to Israel:

We must be honest in saying we have disagreements with the United States, our great friend. The way we see it, Iran is playing with a very weak hand and is bluffing. This lie must be exposed, and they must be given a choice—survival of the regime or a continued race to nuclear capabilities, and they must not be given a gift of tens of billions … Either way, even if an agreement is signed, it will not bind us.

One of the Israeli government’s main concerns seems to be that once a deal is reached between Washington and Tehran, the US will seek to block the covert attacks on Iran’s nuclear facilities that have become a staple of Israel’s strategy of delaying if not preventing Iran’s march towards acquiring a nuclear-weapons capability. According to a report in the New York Times, ‘Israeli leaders say they want a guarantee from the Biden administration that Washington will not seek to restrain their sabotage campaign, even if a renewed nuclear deal is reached.’

This is unlikely to be acceptable to Washington because Tehran can use these attacks as a justification for backing out of the nuclear deal and resuming uranium enrichment and stockpiling activities that would be prevented by a revived JCPOA, thus negating the very purpose of such a deal.

Moreover, the US and Israel differ in their assessment of the state of Iran’s nuclear program. Washington believes that so long as Iran hasn’t moved to develop a bomb it doesn’t have a nuclear military program, since it suspended such efforts in 2003. The reimposition of JCPOA restrictions will act as a further deterrent for Tehran and prevent it from moving towards weaponisation. On the other hand, Israeli officials assert that Iran has continued a clandestine effort to acquire a nuclear capability and a return to JCPOA won’t stop Tehran from reaching its goal.

The divergence between American and Israeli assessments of Iran’s nuclear capability and the utility of a nuclear deal in this context may be the major overt manifestation of their different approaches towards Iran. But the differences go much beyond that issue, according to leading Iran analyst Trita Parsi:

The answer lies in understanding that the details of the deal are not the real problem [between Israel and the United States]. It’s rather the very idea of Washington and Tehran reaching any agreement that not only prevents Iran from developing a bomb, but also reduces US–Iran tensions and lifts sanctions that have prevented Iran from enhancing its regional power.

The fundamental reason for Israel’s opposition to a revival of the JCPOA appears to be a fear that it may cause a shift in the balance of power in the region in favour of Iran. That that may well happen is borne out by the fact that just the revival of negotiations in Vienna has led to a change in the postures of Iran’s regional rivals, Saudi Arabia and the UAE in particular, towards Tehran. Both these countries had vociferously opposed the original nuclear deal but have now come around to endorsing its revival. They have sent other signals, including at high-level meetings, indicating their desire for a rapprochement with Iran.

Such approaches have also been fuelled by Saudi Arabia’s and the UAE’s realisations from the time of the Trump administration that the US is unlikely to come to their aid in the event of a confrontation with Iran. The disorderly American retreat from Afghanistan has augmented the feeling among Iran’s Arab rivals that Washington has downgraded the strategic importance of the region, making it imperative for them to find a modus vivendi with Iran.

In this context, the likely impact of a revival of the JCPOA on Iran’s major Arab neighbours has the potential to knock the bottom out of Israel’s policy towards these countries, which has been based on the assumption of mutually shared antagonism towards Iran. The changing attitude of Iran’s neighbours towards Tehran may be the first sign that the balance of power in the region and the calculus it was based on are undergoing a major transformation to the detriment of Israeli interests. This realisation seems to be driving Israel’s strident opposition to the renewed nuclear deal more than the stated reason that it could legitimise rather than retard Iran’s nuclear capability.