Letter from Washington: Saudi Arabia, Iran and America’s new Middle East headache

Washington’s management of its wobbly and contested Middle East policy has just become whole lot more difficult and complicated with the worsening of tensions between Riyadh and Tehran following the recent Saudi execution of an elderly Shiite cleric on dubious terrorism charges.

On the one hand, there’s Saudi Arabia, the uncontested leader of the Arab world and a long-lasting ally of the US; and on the other hand, Iran, the leader of the Shiite community and a country with which the US wants to develop a more constructive relationship. But more importantly, Washington needs both countries to be on board with the Vienna process if the Obama administration is to make any progress in finding a political solution to the never-ending Syrian crisis. And although Saudi Arabia and Iran were both at the initial meeting endorsing the process, their continued participation down the road looks increasingly like a pipe dream.

The Obama administration is indeed worried that this sudden rise in tension between the two key countries in the region will undermine its efforts to stop the horrendous bloodshed in Syria and the consequent human displacement and misery that it generates. Accordingly, Secretary of State John Kerry has been busy working the phones talking to the Saudi and Iranian leaders and officials in an attempt to de-escalate the situation. However, his efforts don’t seem to have had much impact.

Not only has Saudi Arabia broken all diplomatic relations with Iran and stopped all commercial flights between the two countries following the storming of its embassy in Tehran, but most of Riyadh’s Sunni allies in the region have joined it, in various degrees, in severing their ties with Iran. That will further harden the Sunni-Shiite sectarian divide and may well have far-reaching implications for the long-term stability of Saudi Arabia, where 10% of the population is Shiite. Importantly, most of the minority Saudi Shiite population lives in the eastern part of the kingdom where the oil fields and refineries are located. Reportedly, the Obama administration was privately critical of the Saudi Government’s decision to execute the Shiite cleric, fearing that it would create a vigorous Iranian reaction—which, in the end, happened regardless.

The tensions between the two big actors in the region are nothing new. However, the last time diplomatic relations were severed was in the 1980s during the Iran–Iraq war, when Saudi Arabia and its Arab Gulf allies actively financially supported Iraq’s Saddam Hussein in his conflict with Iran. But what’s worrisome today is how quickly tension has risen between the two sectarian rivals, with Iran accusing Saudi Arabia of conducting airstrikes on its embassy in Yemen. (A Saudi-led coalition has been battling Iranian-backed rebels since March 2015 in an attempt to restore the legitimate national government of Yemen.) And although Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman (son of King Salman) has stated that Saudi Arabia doesn’t want war with Iran, this latest development doesn’t augur well for the future of bilateral relations.

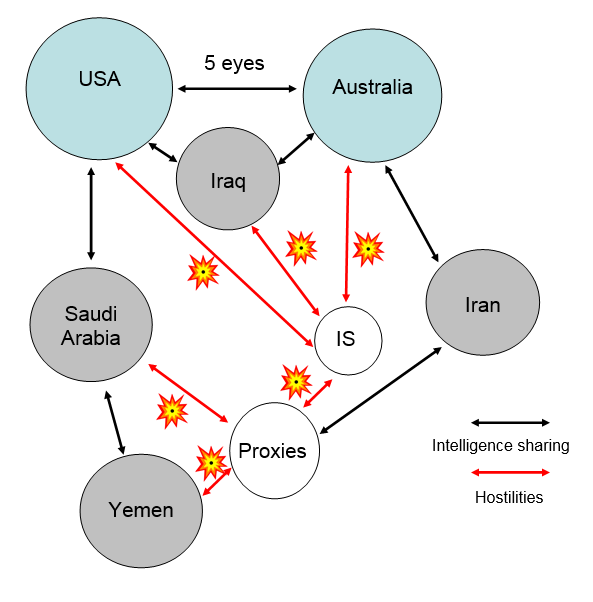

But as everyone knows, a proxy war has already been taking place between the two rivals for the better part of four years, with Tehran supporting Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, head of a minority Shiite sect, and Saudi Arabia backing the anti-Syrian government armed groups. However, the present scrap between Iran and Saudi Arabia underscores the more troubling differences: those between Riyadh and Washington.

During most of Obama’s tenure, there have been deep differences between Riyadh and Washington on how to deal with Middle Eastern issues. The Saudi monarchy has been particularly critical of the US’ willingness to cut Egyptian President Mubarak loose during the Arab Spring; its early refusal to support the moderate opposition against President al-Assad and its failure to act on the famous ‘red line’ in Syria; and, most importantly, its nuclear deal with Iran last year. As seen from Riyadh, this American approach deeply worries the House of Saud, sensing that Washington is gradually loosening its ties with the Kingdom and beginning to lean towards Iran.

In light of the underlying US–Saudi tension, it isn’t too surprising to read (although generally only stated privately) that the Saudi Deputy Crown Prince reportedly said ’the US must realise that they’re ‘the number one’ in the world and they have to act like it’. Such public statements won’t help move matters forward.

In reaction to the perceived lack of US leadership in the Middle East or in response to Washington’s criticism of Saudi Arabia’s failure to pull its weight in fighting the Islamic State, Saudi Arabia unexpectedly launched an ‘Islamic military alliance’ in mid-December 2015. And although it was welcomed by the US administration, it’s unclear how this motley group of 35 Muslim countries—many of which hadn’t even been consulted prior to their inclusion—is supposed to achieve its stated aim of ‘coordinating mutual anti-terrorism assistance all over the Islamic world’. What is clear, however, is that, though that alliance is more symbolic than anything else, as seen from Tehran, this grouping very much looks like an anti-Shiite alliance. Only three Muslim countries—Iran, Iraq and Syria, all majority Shiite or Shiite-dominated states—aren’t included. No wonder then that Iran reacted to the Saudi execution of the Shiite cleric as it did.

It’ll be critical for the Obama administration to diffuse this ever-growing tension between Saudi Arabia and Iran as quickly as possible. And although it’s unlikely that tensions will eventually lead to direct armed conflict between the two Gulf countries, it’ll probably lead to an increase in military support for each other’s regional, non-state proxies. So let’s hope Washington is up to the task of hosing down this latest Iranian–Saudi scrap because it’s those living in this already unstable and war-torn region who would suffer as a result of increased tensions.