Trump’s Iran strategy: policy implications for Australia in the Middle East and Asia

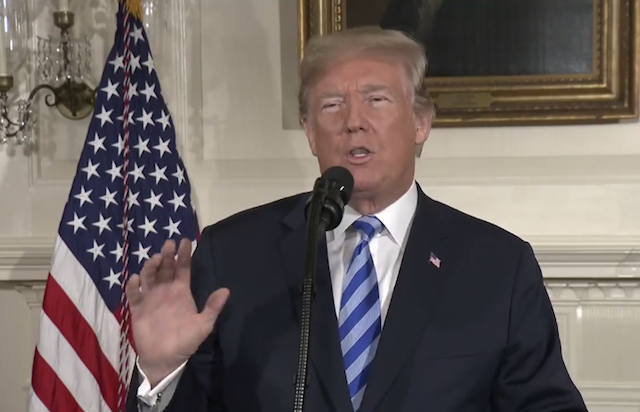

Donald Trump’s ‘Iran strategy’, summarised in a White House media release on 8 May and fleshed out by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in a speech in Washington on 21 May, has significant direct and indirect policy implications for Australia.

Both Trump and Pompeo made it clear that the US withdrawal from the JCPOA nuclear deal is only one part of a broader strategy to end Iran’s ‘malign activities’ regionally. Options within the strategy include forcing ‘regime change’ by breaking Iran’s economy if the Iranians fail to meet all US demands.

Both men also confirmed that the economic interests of the Europeans and others—including, by implication, Australia’s—are expendable unless they coincide with Trump’s ‘my way’ strategy. For Australian policymakers, it must now be clear—if it were ever in doubt—where Australia and others fit within Trump’s worldview.

Trump is highly egotistical and unconventional—a deal-maker, a risk-taker and a firm believer that might is right. His supporters see him as gutsy and outcomes-driven. He makes things happen, and is refreshingly unconstrained by stodgy international norms of diplomacy. His detractors see him as unpredictable and untrustworthy, whether dealing with friends or foes. But many see Trump as a mix of both, depending on the circumstances.

Trump’s overriding commitment, as for all his predecessors, is to put American interests first and make America great again. All his actions derive from this. He interprets—or makes up—the rules to accommodate his ‘my way’ strategy. But this hasn’t diminished the importance of the Australia–US bilateral relationship.

On most major foreign policy issues, US and Australian interests have generally coincided. Where differences have occurred, the principals and officials have worked through them, drawing on the relationship’s historic goodwill and agreeing to respect and accept differing views.

But changes in personalities and policies serve as a reminder that neither Australia nor other allies and friends can be complacent about their relationships with the US, and that goodwill has its limitations where national interests, however defined, are contested.

In the Middle East, Australian policy objectives broadly coincide with those of the US. We want a de‑escalation of tensions and conflict, non‑proliferation of nuclear weapons, and progress towards security and stability. Where we differ, as in the case of Iran, is in how to reach that goal.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull unequivocally supported the European position in a statement on 9 May, calling for the US to remain in the JCPOA and to work through its issues with Iran within that framework. Australia has a stake in the issue, in both politico/strategic and economic terms. Unlike the Europeans, however, Australia’s not a direct participant in the escalating transatlantic test of wills. Nor does it have billions of dollars in trade and investment under direct threat as a result of Trump’s strategy.

Economically, Australian two-way trade and investment with Iran in 2016–17 was a modest AUS$446 million, comprising exports of $265 million and imports of $181 million. Even so, Australia isn’t completely immune to the direct cost of US sanctions and their chilling effect on new trade. While most of Australia’s trade falls outside the scope of current sanctions, an as-yet-unquantifiable amount is expected to be adversely affected by both US ‘snap-back sanctions’ and other punitive measures.

Nor is Australia immune to potential indirect costs. If US targeting of Iran’s oil exports results in a global shortage of oil, every Australian motorist will be hit by higher prices at the petrol pump. At this stage, other Gulf producers are expected to make up for any shortage, but expectations aren’t guarantees.

Turnbull’s support of the European position could be tested in two possible ways. The first could involve Australia becoming embroiled in a transatlantic stand-off, for example if the Europeans negotiate what they consider an acceptable supplementary deal with Iran that Trump then rejects. That assumes that the Europeans can reach such a deal. Iran’s commitment is a key factor here. If it pulls out of the JCPOA itself, or recommences uranium enrichment, all bets will be off.

The second test could occur if Trump pursues his proposed ‘broad coalition of nations to deny Iran all paths to a nuclear weapon and to counter the totality of the regime’s malign activities’, and asks Australia to join. Pompeo explicitly identified Australia, India, Japan and South Korea—together with other Gulf and Arab states—as countries that he wants in the coalition. He didn’t specify any countries from Europe, Africa or Latin America. Naming the first four countries implies a quid quo pro for US support and solidarity in Asia, which is especially relevant given Trump’s quest to denuclearise North Korea and guarantee freedom of navigation and overflight in the South China Sea.

Whatever the outcome of Europe’s efforts to salvage the JCPOA, it’s essential that the US see Australia’s position for what it is—standing firm on the principle of supporting a UN‑approved agreement, particularly where compliance with conditions has been consistently verified.

Australia should firmly decline any invitation to join a new ‘broad coalition’. There’s no suggestion of a UN mandate for such a coalition, and Australia would be a token player only, with no controlling interest. Also, the proposed coalition’s mandate is wide open, and could extend to an expectation of military support.

Arguably, Australia could contribute considerably more to its Middle East policy commitments from outside, rather than from within, any improvised coalition. Asian quid pro quo calculations don’t apply—Australia already fully pulls its weight in the Indo-Pacific.

While the Middle East is important, the Indo-Pacific is crucial for Australia. It’s Australia’s primary area of political, military, economic and strategic interest. It’s where the Australia–US bilateral relationship counts most. The challenge for Australia is to ensure consultation on how to reach mutual goals without compromising its interests.