Iran’s role in the latest Gaza conflict

References to Iran have been glaringly absent from commentary on the clash between Israel and Palestinian factions in Gaza, even though two primary terrorist organisations, Hamas and Islamic Jihad, have effusively praised Tehran and its regional proxies for providing their military capabilities and finance.

Moreover, the way the conflict was framed both by the Gaza groups and by Iran’s broader regional network, from Hezbollah in Lebanon to the Houthis in Yemen, makes it clear that they all view their regional battles as mere fronts in an integrated transnational jihad directed against Israel by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

As Islamic Jihad and Hamas have repeatedly asserted for years, they would have little capacity to start these wars against Israel without IRGC training, funding, arms transfers and expertise. Not only does Iran provide arms and rockets, but it has also established local production capability for all its proxies and trained operatives externally in the technical aspects, even custom-designing cruder rockets like the Badr-3 that can be manufactured with ease in Gaza.

One Islamic Jihad official, Ramez al-Halabi, declared: ‘The mujahideen in Gaza and in Lebanon use Iranian weapons to strike the Zionists. We buy our weapons with Iranian money. An important part of our activity is under the supervision of Iranian experts. The contours of the victories in Palestine as of late were outlined with the blood of Qasem Soleimani, Iranian blood.’

Hamas’s Gaza chief, Yahya Sinwar, said that his group’s ‘complete gratitude is extended to the Islamic Republic of Iran, which has spared us and the other Palestinian resistance factions nothing in recent years. They have provided us with money, weapons, and expertise. They have supported us in everything … They weren’t with us on the ground, but they were with us through those capabilities.’

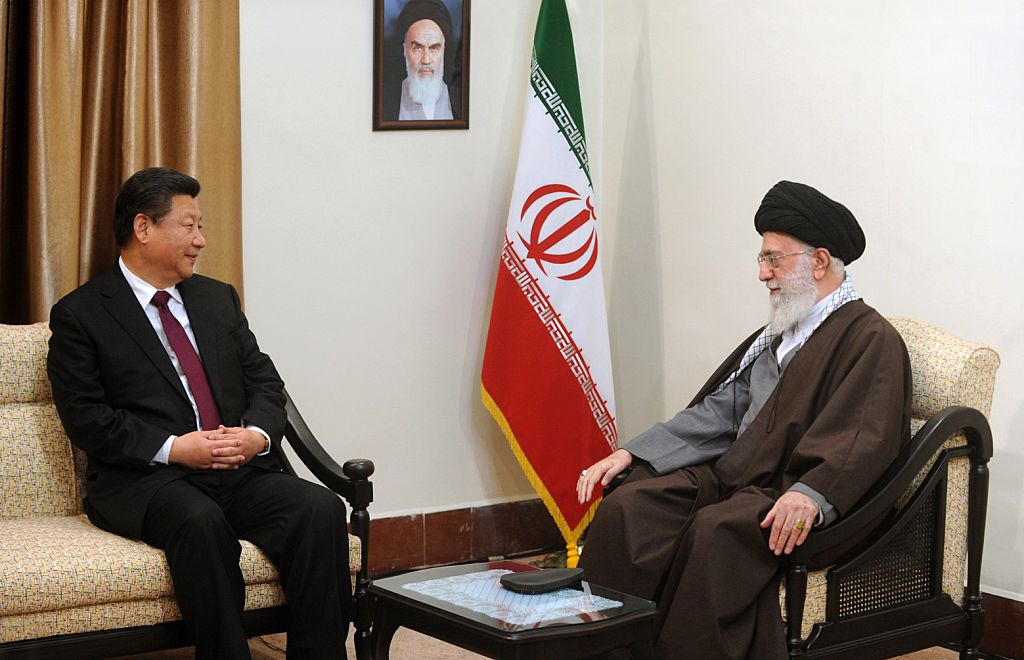

Hamas’s overall leader, Ismail Haniyeh, thanked both IRGC chief Hossein Salami and the leader of its Quds Force, Ismail Qaani, and both Haniyeh and Islamic Jihad leader Ziyad al-Nakhalah wrote letters of thanks to Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

None of this is particularly new. In 2018, Sinwar said that Hamas, Hezbollah and the IRGC ‘work together and coordinate and are in touch on an almost daily basis’. During the latest fighting, he asserted that there had been ‘a high level of coordination’, which was underlined by Hezbollah’s deputy secretary-general, Naim Qassem. The Hezbollah-linked Al-Akhbar daily even claimed that a joint military operations room was established in Lebanon to oversee the conflict, staffed with officers from Hamas, Hezbollah and the IRGC.

What was new in this round was the very open support of the Houthis, both practically and rhetorically. Once a ceasefire was declared, representatives from Hamas and Islamic Jihad gave glowing speeches in Sanaa praising the Houthis for their role in the ‘victory’, and the local Hamas representative bestowed an award on the Houthis for their financial and logistical support.

During the conflict, the Houthis were fundraising for the war effort. In Syria, the Houthi representative reportedly met with Islamic Jihad’s representative to confer about the fighting.

Integration among all of Iran’s proxies reportedly went even beyond this. According to Al-Akhbar, the Houthis contacted Hamas to ask for coordinates inside Israel in a bid to target them with Yemeni missiles and drones. However, Hamas informed Sanaa that the situation in the battlefield was ‘very good’. An unverified report by IRGC-linked Mashregh News claimed that a Yemeni from the Houthi stronghold of Saada was killed in Gaza during the conflict, becoming ‘the first Yemeni martyr in the fight against the Zionist enemy’.

The Houthis, a longstanding Iranian proxy, view their war in Yemen as part of the regional IRGC jihad to destroy Israel, hence their slogan, adapted from Iran’s own: ‘Death to America! Death to Israel! Curse on the Jews! Victory to Islam!’ Comments like those of Houthi politburo member Abd Al-Wahhab Al-Mahbashi (‘The only path is the path to Jerusalem, the path of Jihad against the Jews’) are ubiquitous, and the Houthis openly recruit Yemenis to ‘liberate the Al-Aqsa Mosque’ in Jerusalem.

Rockets and drones were launched from Lebanon and Syria, and possibly Iraq, by Iran’s proxies, indicating coordination across all the fronts. Islamic Jihad’s al-Halabi summarised this coordination, saying: ‘The axis between Jerusalem and Beirut, the axis between Jerusalem and Baghdad, the axis between Jerusalem and Damascus, the axis between Jerusalem and Sanaa, and first and foremost, the axis between Jerusalem and Tehran—it is a victorious axis.’

Al-Akhbar observed that this new round of fighting was different because of the intertwining of the efforts of all of the IRGC’s regional clients and proxies. That, said the report, was ‘a new equation established by the resistance forces in the last battle’, something recently reiterated by the IRGC’s Iraqi proxy Kataib Hezbollah, which declared its ‘entry into deterrence equation’ against Israel should there be another war.

Given how integrated the Palestinian terrorist factions are in the IRGC proxy network, and how operationally dependent they are on it, it’s not clear why media and other commentary almost universally failed to mention the central Iranian role.

The longstanding aim of both Hamas and Islamic Jihad is to destroy Israel and to establish an Islamic state. Their war has little relation to tensions in Jerusalem, though many promote this linkage. Rather, it is an outgrowth of Iran’s ongoing pan-Islamic crusade against Israel’s existence.