Unpacking Indonesia’s civil–military relations under Jokowi

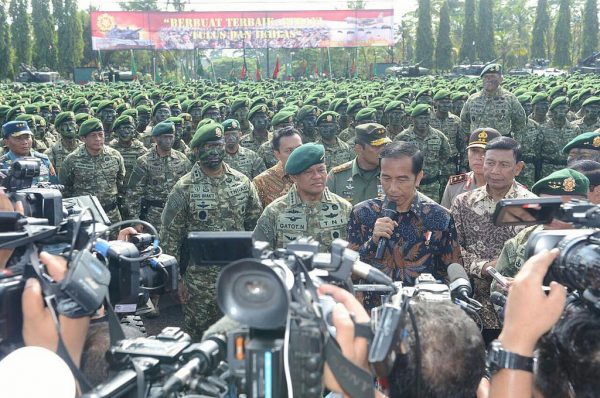

The Indonesian military (Tentara Nasional Indonesia or TNI) turned 72 years old on 5 October. Much of the gung-ho surrounding the anniversary, however, wasn’t about the new weapon systems displayed during the celebration or new strategic plans. Instead, the focus was on TNI Commander General Gatot Nurmantyo—from his explicit order that soldiers must attend public screenings of an old anti-communist movie to his accusations that ‘non-military elements’ were importing arms. Those polemics, when coupled with his previous controversies—from alleged political manoeuvres during the Jakarta election to his brief suspension of language training with Australia—highlight how polarising the general has been since assuming command of the TNI in 2015.

Some have attributed such controversies to Gatot’s political ambitions (see here and here). Others, however, paint the TNI as the problem. They have noted, for example, how the TNI has been expanding its non-military activities, from counterterrorism to anti-drug campaigns, or how retired officers have been playing prominent roles in the Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo administration. Senior officers have also publicly exhibited conservative tendencies as antiquated programs of ‘state defence’ are crowding out technological modernisation plans.

The TNI’s public image should have tanked. But in a recent poll, 90% of the public agreed that the TNI was having a ‘good influence on the way things are going’ in Indonesia. That’s higher than the police (63%) and human rights organisations (82%), and it’s consistent with dozens of surveys over the past decade underscoring the TNI’s high favourability rating (see here and here).

We can make sense of this paradox—mounting criticisms but soaring public popularity—when we consider a few often-overlooked contextual factors surrounding the TNI.

First, Indonesia’s civil–military relations are not an exclusively elite affair between generals and political leaders. The broad conception of civil–military relations emphasises the strong relationship between militaries and their societies. And yet, for decades, most studies and press reports on Indonesia’s civil–military relations have focused on the political contestation between military leaders and the political elite. We know little about the societal relationship between the public and the TNI, or about the effect that relationship has on its intra-organisational dynamics.

That said, the TNI’s popularity seems less about elite politics and more about how the military’s post-1998 withdrawal has led to an increase in the public’s engagement with the police (separated from the TNI in 1999) and other non-military political institutions. Through more engagement, the public unsurprisingly sees the failure and corruption of other institutions more prominently than those of the TNI as an organisation.

Second, it is incumbent upon the president to carefully manage the TNI. Under Jokowi, however, civil–military relations have been on auto-pilot; his ministers—retired generals like Luhut Pandjaitan and Wiranto—handle national security affairs while the defence ministry and TNI headquarters formulate their own policies. Jokowi hasn’t been personally interested in a deeper or closer engagement with the military, and his advisers might feel he shouldn’t spend political capital on it—not when economic development and infrastructure are re-election centrepieces.

To be fair, finding the right balance in managing the TNI has always been difficult. Micro-manage too far, like President Wahid did in 1999, and you have political chaos. Not managing at all allowed conservative voices to dominate, as the Aceh conflict under the Megawati administration showed us. For better or worse, President Yudhoyono took great pains to engage with and manage the TNI. His personal and hands-on approach to the TNI may have even helped stabilise military reform.

In any case, Jokowi can’t easily intervene in military affairs when things go south without sustained investment. It’s extremely difficult to manage civil–military crises when you haven’t built trust or a relationship with your military leaders and the organisation. Such investment is even more critical when you have a TNI commander who’s more willing to engage in public or even political activities.

Finally, the TNI’s recent regressive tendencies are partially rooted in the lack of attention for almost two decades to fundamental issues of organisational reform—from education and training to personnel management. Rather than completely overhauling the military structure put in place by TNI commander Benny Moerdani in 1983, the post-Suharto military leaders preferred to tinker with it (a process dubbed ‘organisational validation’). Aside from the reforms to its political role, the TNI’s overall structure had been modified more than half a dozen times since 1998. The last set of modifications was announced last year and would last until 2019.

With constant tinkering sans fundamental overhaul, personnel policies in particular could hardly be professionalised. The incentive system that had rewarded conservative and politically ambitious officers remains. Nurmantyo is not unique in this sense; he’s a product of the height of the New Order era along with his generation who entered the military in the 1980s. As junior officers, they cut their teeth in East Timor and formed the backbone of the New Order’s system of territorial and political control during its peak. But as mid-rank officers, they had to deal with the uncertainty of democratic transition and the TNI’s near disintegration. Finally as senior officers, they had to ‘wait in line’ as promotional logjams plagued the TNI when the retirement age was suddenly lengthened from 55 to 58 in 2004 even as non-military posts shrunk significantly.

Consequently, some of the 1980s generation like Nurmantyo are often more fluent in political strategies and their conceptions of national security tend to be inward-looking and expansive at the same time. They are also, above all, concerned with organisational unity and restoring the TNI’s reputation. When job promotions and post-retirement careers are equally uncertain, staunchly conservative and politically ambitious officers tend to be the norm rather than the exception.

Welcome to The Strategist Six, a feature that provides a glimpse into the thinking of prominent academics, government officials, military officers, reporters and interesting individuals from around the world.

Welcome to The Strategist Six, a feature that provides a glimpse into the thinking of prominent academics, government officials, military officers, reporters and interesting individuals from around the world.