Indonesia’s defence minister, Ryamizard Ryacudu, was one of my first phone calls after becoming minister for defence—a call that made me feel incredibly positive and encouraged. Minister Ryamizard’s commitment to Indonesia and Australia’s strong relationship—and close defence cooperation—is a testament to the enduring partnership between our nations.

He also advised me of his high expectations for our defence relationship. He said that he hopes and expects that, together, we will seek to realise them.

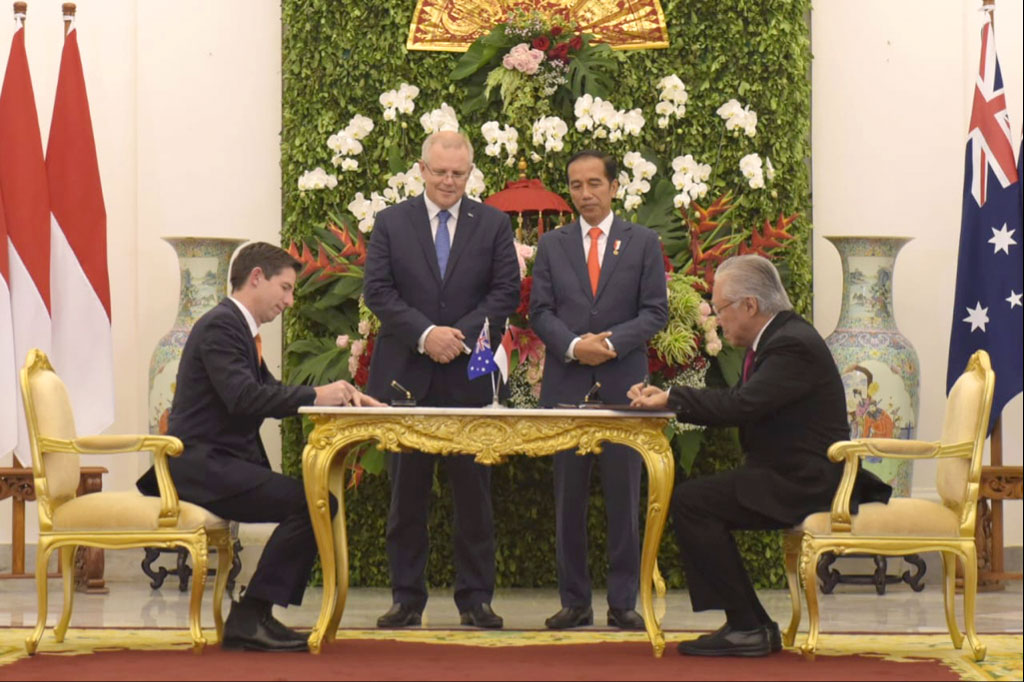

The Australian government’s most recent foreign policy and defence white papers both stressed that a strong, productive relationship with Indonesia is critical to Australia’s national security. This was underlined in 2017 with the renewal of our formal framework, the Defence Cooperation Arrangement.

Right now, Australia and Indonesia engage through a number of strategic dialogues, training and bilateral exercises. Every year there are 15 senior bilateral defence dialogues between our nations. At the operational level, the Australian Defence Force and TNI participate in about 18 military exercises.

These bilateral exercises both increase the ability of the ADF and TNI to respond to specific events or circumstances and increase trust and confidence-building between our countries.

Exercising together creates greater interoperability, deepens the links and understanding between our forces, and places them in a better position to cooperate across a number of common security interests.

What’s more, the friendships those exercises forge are institutionalised through IKAHAN: the Indonesian–Australian Defence Alumni Association, which currently has more than 2,000 members. We are, clearly, seeking deeper levels of understanding, appreciation and collaboration—and we need to maintain this momentum.

We need to maintain it for its own merits, and because of the shared challenges facing our region. The world’s attention has shifted to Australia’s and Indonesia’s doorstep, more so than at any point in our recent history. The Indo-Pacific region is dynamic, evolving, growing and prospering. It is at the heart of the global economy.

It is home to more than half the world’s population. It is the destination for more than three-quarters of Australia’s two-way trade. Both our countries sit at the fulcrum of the Indo-Pacific.

We both have a stake in managing growing strategic competition between great powers in the Indo-Pacific. We are seeing a resurgence of terrorism and violent extremism, and sovereign interests are being increasingly undermined as non-state actors use the cyber domain to extend their reach. Grey-zone tactics or hybrid warfare—activities which remain below the threshold of traditional armed conflict—are being used by some actors to pursue their strategic ends.

Moreover, long-held principles, and the global rules and norms which have underpinned the region’s growth and success, are being challenged.

Those rules and norms, and the institutions which have developed them, have served both Australia and Indonesia well. They can continue to serve us well.

It is incumbent on all nations to work together to strengthen and adapt the global order and an international system that allows all nations to thrive, and to do so in peace.

We need one that is fit for purpose in the 21st century. That is why Australia congratulated Indonesia for its crucial role in ASEAN’s adoption of the ‘Outlook on the Indo-Pacific’ last month. Australia has a similar vision for the Indo-Pacific.

The ASEAN Outlook sends a powerful signal of ASEAN’s commitment to international rules and norms, and to the principles of openness, transparency and inclusivity. We both want an open, inclusive and prosperous region in which the rights of all states large and small are respected.

It is up to us to work together—as close partners, and with ASEAN—so that we can shape our region, and ensure our shared security and prosperity is strengthened, not undermined.

And we must build each other’s capability as part of addressing the challenges we face—challenges neither of us can address alone. There are a number of areas where we can do this. Let me highlight four. First, there is maritime security.

In the years ahead, the Indian Ocean is likely to become a more significant zone of competition among major powers. The threats we face in the maritime domain range from challenges to sovereignty, to smugglers and illegal fishing. They are broad and complex, and require a broad response.

Maritime cooperation by a number of like-minded countries is essential, and Australia and Indonesia are natural partners in this respect. We share a long maritime boundary in the Indian Ocean.

We both desire a stable and secure maritime order: one with unimpeded trade; adherence to international law, including UNCLOS; and freedom of navigation and overflight. We are also both respected regional maritime security actors, with good track records.

To date, Australia and Indonesia have encouraged cooperation through our respective multilateral maritime security exercises, Kakadu and Komodo.

We have both chaired the Indian Ocean Rim Association. If we further deepen our cooperation in the Indian Ocean—at the bilateral level, and with other partners, particularly India—our confidence and our ability to maintain maritime security in a vast ocean will grow. For example, our membership of the Indian Ocean Rim Association—as well as the Western Pacific Naval Symposium—gives us the opportunity to bridge maritime security cooperation with our partners in the Indo-Pacific. That will benefit us, and the region.

Second, is in the area of counterterrorism. I have seen firsthand the shocking toll of terrorism: not only its victims, but their friends and family.

And the psyche of both of our nations. Australia and Indonesia—as well as our regional friends and neighbours—all have an interest in cooperating to defeat terrorist movements, wherever they happen to arise. At a bilateral level, our two countries have worked together to counter terrorism for over two decades.

Last year, for example, we marked 25 years of collaboration between our special forces. Terrorism has always been a collective challenge requiring a collective response. Minister Ryamizard has demonstrated strong leadership by championing the Our Eyes initiative among ASEAN states—a significant step forward for the region’s commitment to information-sharing.

And I very much look forward to Indonesia hosting the next iteration of the Sub-Regional Defence Ministers’ Meeting on Counter-Terrorism—another opportunity for us to make further inroads.

Australia remains firmly committed to working with Indonesia and our other Southeast Asia security partners to combat the shared threat of terrorism. We have a plan to do this. We will increase bilateral and regional information and intelligence sharing and do more to impart the ‘lessons learned’ by our armed forces, and we will, as I have said, strengthen maritime defence cooperation.

Once again, a collective response to a collective challenge.

Third, in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. At the same time as the Indo-Pacific’s security environment is becoming more uncertain, so is its natural environment. Of course, cooperation between the ADF and the TNI to respond to such challenges is not new.

From the TNI’s assistance to Australia following Cyclone Tracey, to the ADF’s support for Indonesia’s recovery efforts last year in Sulawesi, our forces have been working together and building our proficiency. Natural disasters do not recognise national borders—and it is reassuring to have strong, close friends in time of need. Friends who understand you. Friends you trust.

In the years ahead, Australia and Indonesia will need to continue working together to respond to a growing number of humanitarian situations in the region, or our own countries. When it comes to humanitarian and disaster relief, Australia and Indonesia have different capabilities, but a remarkably common approach. It is an approach grounded in our shared desire to alleviate suffering, and do so as quickly as possible. I only see that as a positive.

It means opportunity: the chance to leverage each other’s distinct knowledge and skills so that we can more effectively respond to future events. And we must share these lessons broadly, in a multilateral way, with our other regional partners.

Fourth, in peacekeeping.

Peacekeeping is an important part of Australia and Indonesia’s defence relationship, and it represents yet another opportunity to drive understanding as well as interoperability, capability development and people-to-people links. It is also a critical line of effort if we are to achieve global peace and security.

Australia is proud to co-chair the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus Experts’ Working Group on Peacekeeping with Indonesia. We value the close cooperation this has fostered.

Indonesia has a wealth of mission experience, and is a top-10 contributing nation to United Nations’ peacekeeping operations. It has many lessons to share—lessons Australia would welcome. While Australia may have a smaller troop contribution compared to Indonesia, we do provide niche capabilities and training.

And there are many opportunities—through training, exercises and education—for the ADF and TNI to further develop our respective capabilities.

Furthermore, by building on our own relationship we can also assist our regional partners to develop their peacekeeping capabilities offering wide-ranging lessons, expertise and practical support. I firmly believe that Australia and Indonesia are stronger, safer and more secure when we work together.

There is no doubt that the security challenges facing the Indo-Pacific region—our collective home—are complex, and unpredictable.

No country can or should carry the burden alone. Australia and Indonesia have an open and honest relationship. We have worked hard to know each better and build trust. We are friends in the truest sense, and we have much to gain from deepening our bilateral relationship.